Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

Cultures of Nothing:

Popular Culture in the Museum Context — Hitchcock, Hip Hop, and the Hockey Hall of Fame

Producer/Sponsor: Organized by the MMFA and presented by Investment Group. Other sponsors included Metro, Minister of Culture of the Government of Quebec, La Presse, British Consul, National Film Board of Canada, and the Minister of Culture and Communication of the City of Montreal

Curator: Guy Cojeval (Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) and Dominique Païni (Cinémathèque Française)

Dates: 16 November 2000 to 17 April 2001

Accompanying publication : Hitchcock and Art: Fatal Coincidences, ed. Dominique Païni, Milan: Les Editions Mazzotta, in collaboration with the MMFA, 2000.

Brief synopsis: The focus of this exhibit was to make direct connections between Hitchcock's film works and the tradition of the painted world and the sculpted image, these being the key elements of an art gallery. The exhibit was divided into five main themes that the curators found in Hitchcock's complete oeuvre, and used contemporary as well as classic works of art to support their analysis. The themes were: "Women," "Desire and Double Trouble," "Disquieting Places," "Sheer Terror," and "The World as Spectacle and the Spectacle of the World."

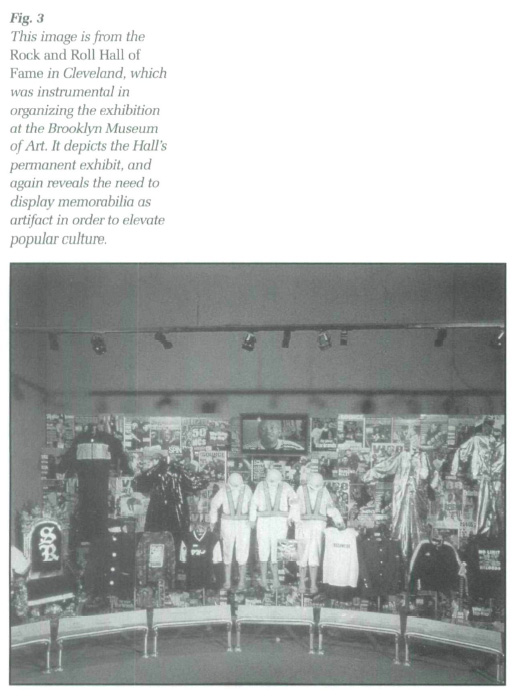

Producer/Sponsor: Levi's, Def Jam Records, Brooklyn Museum of Art Restricted Exhibitions Fund, National Endowment for the Arts. Media sponsors: Rolling Stone Magazine, 360hip-hop.com, Hot 97 FM Radio. The exhibit was organized by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Brooklyn Museum of Art

Curator: Kevin Powell

Designer: Alternative Design Inc.

New York dates: 22 September to 31 December 2000

Brief synopsis: This temporary and popular exhibit justified and validated the hip hop subculture, and attempted to be particularly sensitive to the people it showcased and attracted. The show was presented chronologically, and emphasized the different components of hip hop, making sure they included not only the music, but fashion, break-dancing, and graffiti. Videos, photos, music, text panels and multiple cases of original items were essential in conveying this exhibit's message.

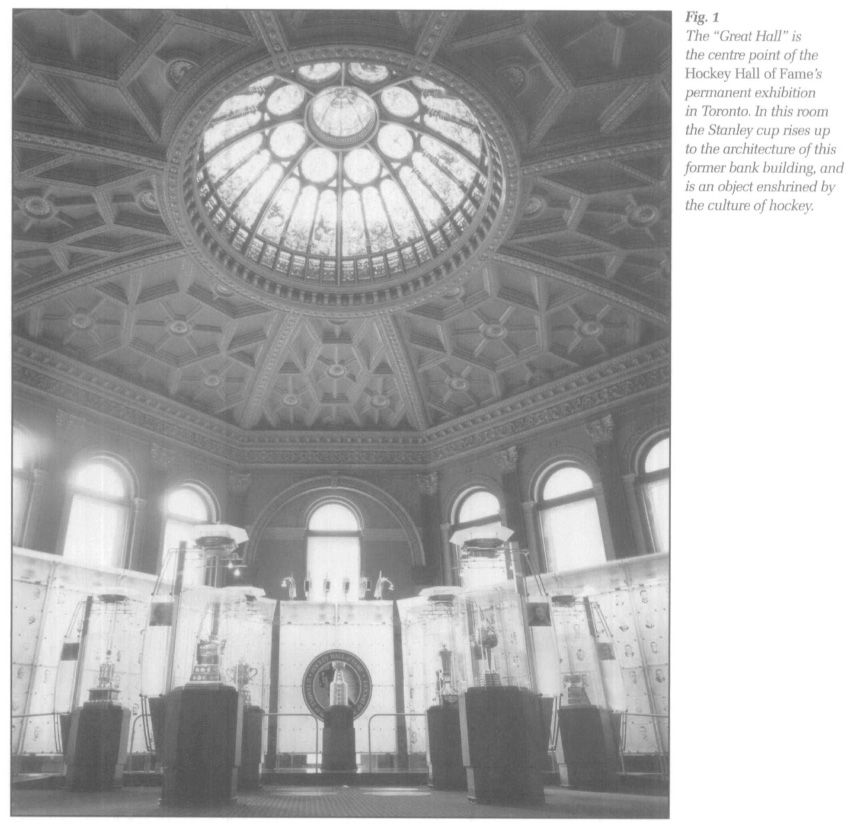

Producer/Sponsor: Esso, Blockbuster, TSN/RDS, McDonald's, Coca Cola, Ford, Royal Canadian Mint, IBM, UPS, Bell

Curator: Phil Pritchard

Duration: Permanent

Accompanying Publication: Hockey Hall of Fame Magazine is a quarterly visitor's guide, published by St Clair Group Investments of Toronto.

Brief synopsis: The Hall, located in the heart of Toronto's downtown, offers its visitors a mammoth and colourful display of the evidence of hockey's culture, its history, its legends, and equipment. Half of the exhibit was designed for the visitors' active participation, and the other half was devoted to hockey's artifacts. Memorabilia collected by die-hard fans was institutionalized in its collection.

Spectacle and Show — This is Entertainment After All...

1 People with the means to plug and play into pop culture demonstrate their power as consumers through three broad levels of participation, where each can then be reduced and replicated through essential items that represent their experience. The first is at home in private, where recorded music, films on home video, and televised coverage of sports events simulate the sensation of a "real" experience within a fan's personal space, mediated through technology. The second level is within a culturally-specific venue in the public sphere where fans meet fans (for example, in a hockey rink, movie theatre, or concert hall). And finally, the third is the most detached and abstract level of a culture's representation, found in an art gallery, museum, or hall.

2 The difference between these categories relates to a fan's perceived reality and their relationships with the dominant culture. This paper examines three exhibits that took icons from the popular culture of Western entertainment and placed them in the museum context. The results are obvious, as the institutional environment engulfs them in its codes of display and reception, and attempts to justify their inclusion in that context. The function of having these cultures on display in an elite institution is to change our attitudes towards them. Here we pay special attention to memorabilia, their significance, and die ways in which the material history of a subculture can be used to define its meaning for greater society. A close reading of how these cultures were put on display reveal a number of problems and contradictions. All three exhibits involuntarily fetishized objects and played upon their audience's sentimental attachment to the cultures presented. All three also dedicated space to the (non)influence of women. They either contained women in their own display cases, or problematically peppered them throughout their exhibitions in a superficial treatment that maintained the status quo.

3 The definition of "popular culture" will refer to the inclusive norms and practices of mass society. Pop culture is meant to be consumed, whether it be by the senses or with the means of the wallet. It represents the tastes of a group of people, and therefore the word 'subculture' in the same context is a more specific and smaller group with its own language, icons, and practices that contribute to the larger rubric.

4 In these types of exhibitions, memorabilia and the material culture of that group's history are essential in announcing its existence to a wider audience. For people who are not familiar with the subculture, mundane objects are imbued with new meaning by simply being included within a museum's walls. For those "in the know" who are intimately connected to every hockey game of the Montreal Canadiens, for example, authentic originals act as the ultimate collection of keepsakes.

5 For fans, artifacts and memorabilia act as memory triggers that directly relate to past events, and create a mysterious satisfaction for the people who are drawn to them. Such objects will condense time and space, because they become a conduit that immediately connects a receptive audience to previous spectacles of their culture. These kinds of examples of material history, then, provide the link between the real events and a fan's desires to actively participate in diem. An original number 99 hockey jersey worn by Wayne Gretzky, for example, is a material object that a viewer can get physically close to in the present day. By being in its proximity, the object fulfills the viewer's desires to have been there when the shirt was worn, and supplants those past desires with an immense and immediate satisfaction of having an active connection to the original event. It is the object's capacity to fulfill these desires that creates the intense reverence for cultural relics and gives them value.

6 In the museum setting this relationship can be uneasy, as some of the objects found in the Hockey Hall of Fame and Hip Hop Nation shows demonstrate. Museums and galleries often add items to their collections based on cultural estimations of value. What traditionally makes something valuable is its uniqueness, authenticity, age, legacy, or historical significance. When mass-produced objects handled by a culture's celebrities go on display to illustrate the history of that group, the original concept of the museum artifact is stretched. In Hip Hop Nation, items such as key chains, sneakers, and pants found themselves in the ever-so-important display case. Similarly, the Hockey Hall of Fame contained hundreds of hockey sticks, pucks, and jerseys, but each one was deemed special because of its attachment to a single player of note, or its connection to a decisive moment in hockey history.

7 Object-centred displays scream out to their viewers that what is kept behind glass and guarded is important. Outside of the museum, memorabilia are only important to someone who wants to remember them. Consistent with museum display techniques, the memorabilia of popular culture are tagged as things that are worth remembering for everyone, and in the art gallery context, follow the Duchampian tradition of questioning exhibit content by including everyday objects.1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 18 In the Hitchcock show, visitors are first introduced to a room with an elaborately constructed display of everyday objects. We expect museums to display artifacts, not intentional fakes. But in this setup, the question as to whether what was on display were authentic original props or not was unclear, and the museum did not provide this information in written form. When asked, a museum spokesperson stated that including original props would have elevated them to art status. Instead, their intention, he insisted, was to have objects which innocently represented the climaxes of Hitchcock's classic films. But these display techniques undercut their intent. In this room, each case was lit by precision lighting that focused on a crimson satin cushion, a film still, a key prop, and a descriptive brass plaque. Dramatic music composed by Bernard Herrmann for Hitchcock's films played in the background of this one room, and added to its tense atmosphere. Each film was reduced to an object: a doll, a knife, a pair of scissors. The room's atmosphere was so carefully constructed that visitors were compelled to filter between the twenty-one cases, silently observing common things which had accrued an aura beyond their original function. And this excessive attention and near reverence for "stuff' is precisely the definition of the word "fetish." The setup was incredibly misleading, and when told that these objects were not the authentic film props, some visitors even remarked that they felt cheated.

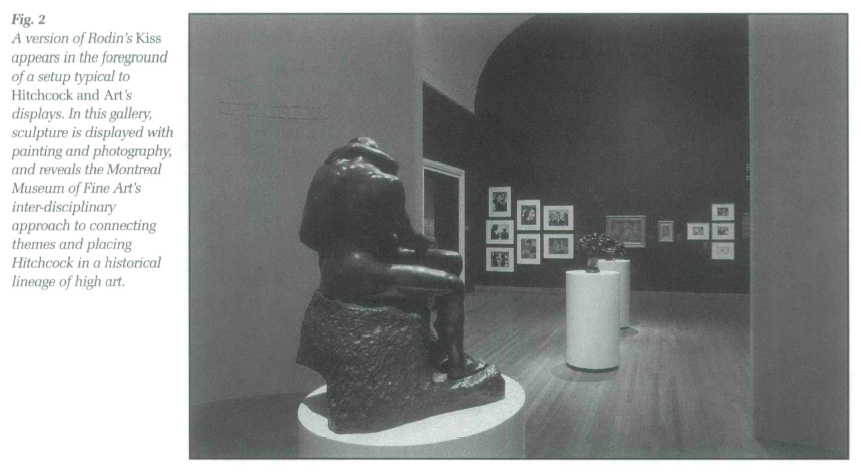

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 29 For the remainder of the Hitchcock show, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts put high art on display, and was thus much more successful at averting the fetishizing process. In our society, art has a symbolic layer of meaning that is missing in everyday objects. By including art that is said to represent the film maker's inspiration, the art museum managed to avoid the cultish elements found in the other exhibitions. The Hitchcock exhibit emphasized the personal genius of the film maker. Its curators believed that Alfred Hitchcock was brilliant at relating the ideas found in the traditions of high art to the tastes of the popular audience. When first released, his films were intended for a mass public, but over time they have attracted a cult of film-goers interested in Hollywood's classic narratives. Therefore bringing this star director to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts places his work under the lens and on par with the painted canvas, and extends the tradition of high art to include him.

10 Like all of the relationships between fans and stars, the relationship between Hitchcock and his devotees is complicated. The MMFA exhibit did not cater to the common denominator. It had a cold edge to it, perhaps inevitable because of the nature of the man under the spotlight. It also drew attention to Hitchcock's hypothetical inspirations rather than the man himself, and thus avoided the bizarre attachment to personal mementos found in the other shows. A very authoritative feel is magnified by the quiet of the art gallery, forcing the viewer of the exhibit to become passive.

11 In this way the Hockey Hall of Fame and Hip Hop Nation differed from the Hitchcock show because they explored as well as provoked the intensely devotional relationship between stars and fans. Because their goals were to give an overview of each respective culture, for the most part there was only a cursory treatment of the many individual stars they attempted to showcase.

12 But perhaps the best example of a spotlight that breakes this rule was the Hockey Hall of Fame's ongoing major focus on Wayne Gretzky. In the very same exhibit as the Coca Cola Rink Zone and the Blockbuster Video Dressing Room lies the display Wayne Gretzky, the Legend. Although not explicitly supported by any major corporation, there are well placed inferences to Esso, the space's official sponsor. No other player gets his own room filled with copious examples of product endorsements, an abundance of personal hockey sticks, or a cleanly laid out material history of an entire hockey career. This room acts as visual inventory of his experiences and triumphs in the commercial life of a modern sports hero. Whereas Rocket Richard had to sell used cars to make ends meet, Gretzsky sells his smiling face to Sugar Crisp. This testament to the commercialization of sports underlies what is on display in the Hockey Hall of Fame, echoing the exhibit's glossy and commercial feel.

13 Because this is an institution of hockey specifically, it attracts a crowd that is trained to consume these images. Architecturally, it is located on the concourse level of a modern commercial space, which includes shops and restaurants. It uses the veneer of an old bank building to maintain the façade of a museum while retaining an aura of wealth and masculine power. The institution is a hockey shrine with no other focus, and whose patrons are more often than not jersey-wearing, stat-knowing, cap-sporting, enthusiastic and emotional males. Contrary to the stereotypical image of the male sports fan, their visible expressions of awe were evidence of the aura of memorabilia.

14 The audience of these three exhibits comprised predominantly two types of viewers— one that regularly visits the art museum, and the other that was specifically attracted to it because it reflected their interests and/or lifestyles. Hip Hop Nation served as an excellent example of this phenomenon. The controversial and often aggressive style of this culture had the potential to make the more conservative art gallery patrons uncomfortable. The curator anticipated these highly skeptical visitors. For these people the exhibit did not explicitly state that it was fine art, but justified its inclusion in the United States' second largest art museum based on hip hop as a billion-dollar industry, its appeal across ethnic and racial lines, and actual cultural impact on North American society. It can be assumed that both types of viewers received these statements differently. Hip hop fans who went to the Brooklyn Museum of Art did not need any justification for their experiences. Instead, these statements functioned as an institutional nod to the perseverance of this grass roots movement turned major music industry.

15 The hip hop show at the BMA celebrated the creation of a culture made from nothing. This show revealed the creativity of New York's ghetto youth, who improvised with the world available to them: cardboard boxes to break dance on, cheap records to scratch-play, a mouth-made beat, and graffiti, the epitome of an urban art form that claims someone else's space. The show's analysis was given in two formats, one written and one aural, and intended for the two types of expected audiences previously mentioned. It was assumed that one type of museum goer would be more interested in reading, while the other would only respond to a visual and musical display of their history.

16 Similarly, the overwhelming visual and audio stimulation found in the Hockey Hall of Fame emphasized the spectacle of the sport itself and turned the hall into a carnival of sorts. As mentioned earlier, the Hitchcock show also used signature orchestrations in its most important room. All three of these exhibits featured background sounds that recreated an aural atmosphere essential to each popular culture, and in the process, went beyond the conventions of usual museum practices. "He shoots, He SCORES!" and "I like big butts and I cannot he" from the song "Baby Got Back" (on Sir Mix-A-Lot's 1991 album Mack Daddy) blasted in the background certainly added to the total experience. Obviously, this stretched the genteel and composed experience usually associated with museum culture.

17 Exhibitions on the subcultures that exist under the larger umbrella of popular culture are intended for everyone's viewing, but it is possible to read between the lines and note discrepancies when it comes to "universal" culture. Does such a culture exist? Who does it really exclude? In the writing of this article, we realized that each of these subcultures considered it acceptable if not normal to marginalize women within their norms. Ideally, the function of a museum is to operate at a distance considered appropriate for objective social commentary. All of these museum displays however, upheld the status quo. Proof of this very problem lies in the fact that curators all made the effort to mention the place of women, but in a token fashion. They failed to criticize women's limited participation, and therefore as the institutions appropriated these subcultures, they legitimized them with little critique.

18 The Hockey Hall of Fame relegated women to two easily missed display cases in the international section of the exhibition. At the Hockey Hall of Fame, eighty-five to ninety percent of visitors we met were men, and women were not independent viewers, but brought along as wives, mothers, and sisters. The two members of the J>A>K>A>L Collective who went to Toronto to visit the exhibit felt distinctly out of place. Being the only single women at the Hall without any male accompaniment to broker the experience located them in male territory feeling isolated. The precise dilemma is feeling this within an exhibit that claims to be universally encompassing. Indeed, there is even merchandise that declares "hockey is Canada." As an all female collective it took us several weeks of critical thinking to see this phenomenon in the first place and deem it important enough to mention. This demonstrates that female exclusion is so pervasive within the pop culture of our society, that it almost went unnoticed.

19 More specifically, Hip Hop as an artistic expression is known for its abusive lyrics that include women-bashing. The Brooklyn Museum of Art show nodded to the role of women in this culture, but at the same time contradicted itself by protecting the existing state of current society. A wall panel stated that "because hip hop is a subculture of the larger American society, it is little wonder that the same patriarchy, sexism and misogyny that permeate all levels of mainstream America are also omnipresent in hip hop." In a larger context this panel is problematic because it does not recognize how this music polices the boundaries of sexuality and defined social roles. These exact critiques were only voiced at the end of the exhibit in a video installation made by young people that explored difficult issues within this cultural movement. This video was the official word of an outside group asked to participate in the show. As a result, the BMA denied taking responsibility for a harsh critique, and instead could get away with simply legitimizing the movement by accepting it as incontrovertible social fact in the museum context Despite all this, the video occupied a pivotal place in the exhibit — right before the giftshop.

20 In the Hitchcock exhibit, we also found the strict definition of women's roles, particular to the vision of one man in the mid-twentieth century. As the curators of this show noted, Hitchcock's "signature style" was the use of typecast women, bleach-blond, fetishized, and depicted as either ice-cold villains, "good girls," or a blend of both. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts disregarded the inherent problems of these portrayals, and instead, considered these aspects as part of historical, cultural, and artistic traditions. Hitchcock and Art was yet another example of the problems of presenting women in pop culture that deserves more attention and further consideration in the exhibit planning process. Although going into a deep sociological analysis is beyond the scope of this review, we would like to acknowledge this discrepancy and identify it as an important point for further research.

21 On September 22, 2000, Roberta Smith published a review of Hip Hop Nation in The New York Times (Section E; Part 2; Page 31). One of her most pointed critiques declared, " I have never seen a major museum exhibition that looks so nearly identical to the requisite gift shop at its end," and later stated that "this show feels like the cross between a mall and a mausoleum." Sure enough, all three shows that we examine here included that requisite gift shop. But after our discussion of memorabilia, it is worth pointing out that these shops perpetuated the object-driven memorabilia craze, and had museums generating artifacts of their own. These consumer goods allowed visitors to bring home a souvenir of these exhibits which, for the most part, were exhibits of souvenirs.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 322 Hip Hop Nation, Hitchcock and Art, and the Hockey Hall of Fame acknowledged their role in elevating and validating the cultures they chose to present. Each museum organized their exhibits around a collection of proud ideas communicated to its viewers through objects. Movies and rap music in this context brought in expanded audiences to high art museums, and thus opened up the elite's cultural arena to new discourses from voices not previously acknowledged. Furthermore, Hockey's permanent institution replicates some museum formulas in order to be a part of this equation. To give such cultures of nothing access to this forum, memorabilia, used as artifacts, are key. The material culture was a good fit within the museum context in an abstract way—the inclusion of popular culture can only succeed when memorabilia are given the same weight as devotional objects.

23 Yet not every institution was comfortable exploring these boundaries, neither accepting responsibility for controversial exhibit content nor their social implications. The established "culture of something" has barely begun to capture the unfamiliar bounds of nothing. In the final instance, "cultures of nothing" can only succeed in the museum forum when memorabilia are respected and represented as devotional objects elevated to the status of museum artifacts.