Articles

The Multiple Roles of the Millworker's Lunch Basket in Central Newfoundland

Abstract

This paper discusses the many circles in which one artifact, the millworker's lunch basket, operates. The basket is a symbol of a permanent job at the local pulp and paper mill, an artifact used in pranks by men while at work, and a basket that many women have packed with great care. The separate spheres of men's industrial work and women's domestic work are both linked and separated by this object. Based on field work and audio-taped interviews with people in Central Newfoundland, the author explores the themes of local acceptance of an outside artifact, women's domestic work in an industrial community, and the role of custom in the work life of a millworker.

Résumé

Le document traite des nombreux cercles dans lesquels évolue un objet, ici la boîte à lunch d'un travailleur d'usine. Il s'agit du symbole d'un emploi permanent à l'usine locale de pâtes et papiers, d'un objet parfois utilisé par les ouvriers pour jouer des tours à leurs collègues de travail, et d'une boîte que nombre de femmes remplissent avec le plus grand soin. Les sphères distinctes du travail industriel des hommes et du travail ménager des femmes sont à la fois reliées et séparées par cet objet. Grâce à des recherches sur le terrain et à des entrevues enregistrées sur bande sonore avec des personnes vivant dans la région centrale de Terre-Neuve, l'auteure explore les thèmes de l'acceptation locale d'un objet extérieur, du travail ménager des femmes dans une collectivité industrielle, et du rôle de la coutume dans la vie professionnelle d'un ouvrier d'usine.

1 The quote above is one woman's memory of how her grandmother's porch looked to her as she was growing up in Grand Falls, Newfoundland.2 The lunch baskets she talks about are a very common sight in the town, an everyday object that travels from home to work and back again. It is a symbol of a permanent job at the mill, an artifact used in pranks by men while at the mill, and a basket that many women have packed with great care. The separate spheres of men's industrial work and women's domestic work are both linked and separated by this object. In this paper I will explore some of the circles in which this object operates: community acceptance of an outside artifact, men's industrial work, women's domestic work and custom.

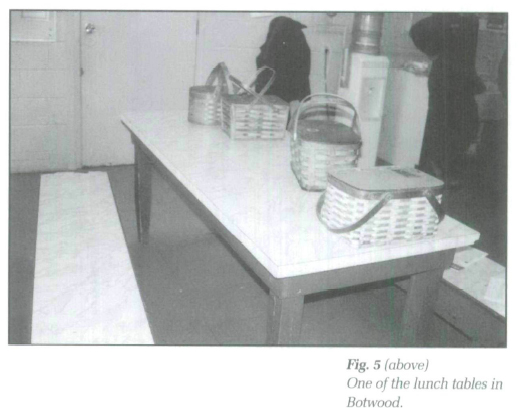

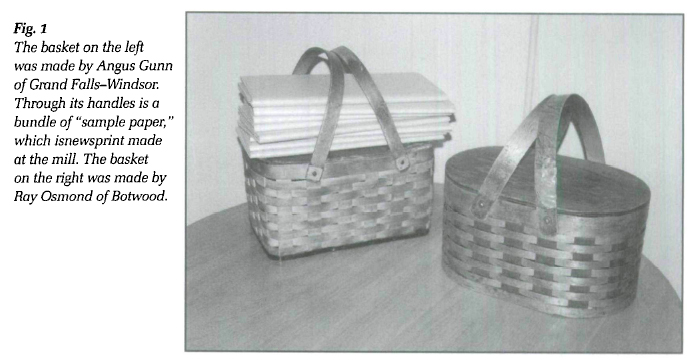

2 The study of everyday objects provides entry into the daily life experiences of the people who create, use and cherish them. My work in Central Newfoundland on artifacts relating to the pulp and paper industry located there has led me to explore the multiple roles of one everyday object in particular: the millworker's lunch basket. Versions of this distinctive two-handled splint style basket exist in the region as both a factory made item and a handmade one. Yet whether it is oval or rectangular, made from steel, juniper, vinyl siding or birch, its form is so recognizable and so symbolic to the local community that all versions are recognized and accepted as a mill lunch basket (Figs. 1, 2, and 3).

3 The mill started operations under the Anglo Newfoundland Development Company (A.N.D. Company). The A.N.D. Company was incorporated in 1905 when a combination of British publishing interests and Newfoundland government officials decided to begin construction of a major new industry in Newfoundland.3 A pulp and paper mill was built at a site on the Exploits River in the interior, and supplied with wood from the surrounding forests. People came from all over the island to help construct the mill and build the town of Grand Falls. Many stayed on to work there and were housed in the company homes that followed the British "Garden City" style and movement.4 From the start, homes were directly and intimately linked with this new industry.

4 The establishment of the mill and its operations was significant to Newfoundland society in a number of ways. There was an out migration of women and men from the outports to the interior in order to seek work with the Company, which offered full time rather than seasonal work and introduced cash wages. The industry has played a role in the cultural life of all the workers and community members who have been affected by its presence. Subsequent owners were Price Newfoundland and Abitibi Price and it is currently owned by Abitibi Consolidated.

5 While the pulp and paper mill in Grand Falls-Windsor produces newsprint, the final product is shipped out through the neighbouring port of Botwood. Between 1996 and 2001, I made numerous visits to the Central Newfoundland towns of Grand Falls-Windsor and Botwood. The goal of my first set of visits was to carry out field work for a museum exhibit I was curating for the Newfoundland Museum. My objective in that exhibit was to display artifacts, photographs, stories and songs that showed the link between community and industry. The goal of my second set of visits was to complete research for my Ph.D. dissertation in Folklore on a related topic, "Negotiating Relationships: Material Culture as Expressions of Identity and Creativity in Grand Falls-Windsor, Newfoundland." I am exploring how identity and creativity are expressed through material culture by examining how millworkers and their families have negotiated domestic relationships, working relationships, and social relationships through material culture, as well as examining how objects can act to both link and separate the realms of work and home. My work is based on audio-taped interviews with approximately fifty people in the region as well as meetings with many more community members.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 26 My field work has given me first-hand knowledge of the impact of the pulp and paper industry. Because my initial work was museum-related, I had the specific task of looking for everyday objects in the home that reflected that a particular person worked with the mill. I encountered extensive connections between the mill and home and between domestic and paid work contexts exemplified in material culture; one such example was the extensive use of "samples" (excess newsprint from the mill in folded sheets) in the home. Samples have been made into colouring pads for children, used as coverings for tables (a "Grand Falls tablecloth" as one woman called them), and to protect freshly washed floors. The paper hats that the papermakers wear during Labour Day parades are also made from sample paper. In neighbouring Bishop's Falls, work and play were conflated in recreational activity, as people remember children making snow balls — or more aptly "pulp balls" — from the pulp that leaked out of the pipe. And a retired railway worker in Botwood made a wooden model of the A.N.D. Company train — so important to Botwood's industrial history — and placed it in front of his house.

7 Most clearly central to the work/home connections, however, was the millworker's lunch basket. This object's history in the community and the stories people tell about the baskets allow the researcher entry into the cultural life of this community as it has been affected by millwork, and shows how people construct their personal and social relationships. One millworker explained how closely the basket is associated with mill identity when he said, "You know a millworker walking down the road because he's got his basket — his wooden basket."5 In another case, a woman who had three sons and a husband working different shifts said of her domestic labour: "Shift work was hectic. I stayed home and cooked dinner. You might have one going on four [o'clock shift] and another might be coming off, so I was cooking meals all day."6 And another spoke of removing useful items from the mill to home: "The lunch baskets weren't for what you could bring into the mill — your lunches — but what you could bring out."7

8 As many of the people I spoke with pointed out, it was often the children who were the ones in charge of bringing lunches to the mill: "A good many times I'd get out of school at twelve and I'd have to run home and get my father's lunch basket. Or you'd just get home from school and here you'd have to lug a lunch all the way back to the mill to drop it off for supper at five o'clock."8 To children, the mill was often a dark, mysterious, almost magical place. To many of its workers, customary behaviour such as playing pranks as a way of initiating a new worker, indicate that they too feel the mill is a place where other kinds of rules apply. One retired worker explained to me how pranks were played on workers who were too eager to leave for home: "This particular day, this fellow swung his arm up through the handles [of the basket] and all he came up with were the handles — the basket was nailed to the floor."9

9 The basket identifies workers within work, family and community. Anthropologist Richard Handler has noted that the "the concept of 'identity' is peculiar to the modern Western world" and provides examples of other cultural contexts in which the concept is absent.10 Using as one of his examples the world of Jane Austen's novels, he writes: "When Austen's narrators or characters talk about what we would today call identity, they use such words as family, friends, connections and relatives."11 His description fits the manner in which I will look at identity in Grand Falls-Windsor as it is articulated through the use of this basket, in order to study how identity is expressed wiuhn domestic, work and social relationships. It is what Handler calls the "web of social relations that places the individual in question with respect to family, connections and social rank."12

The Baskets and the Basket Makers

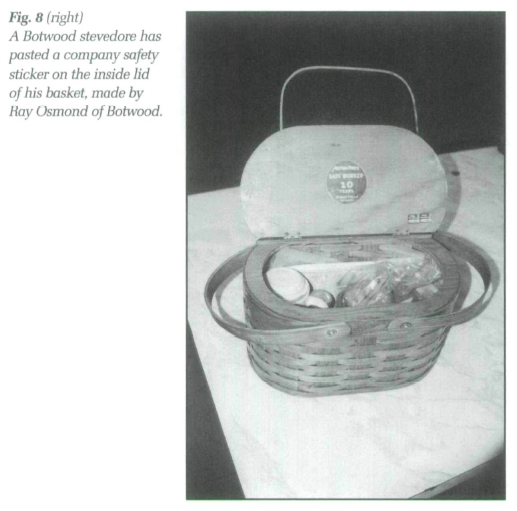

10 Folklorists, anthropologists and others have approached the concept of creativity from a number of angles. Many studies have been done on the concept of creativity within tradition, or the tension between innovation and conformity. Early studies on creativity in material culture include Ruth Bunzel's The Pueblo Potter, in which she notes that: "even the individual of marked originality operates within narrow limits."13 Echoing Bunzel's conclusions, William Bascom in "Creativity and Style in African Art" observed that: "Within each of these distinct styles there is usually considerable uniformity and obviously less creative freedom than was originally believed."14

11 The most popular basket makers in the area have produced baskets that reflect individual creativity within an established norm, what Henry Glassie in The Spirit of Folk Art calls: "a personal version of a collective style."15 In Material Culture, Glassie restates this observation, noting that the object will always display both stability and variability and that "creation always blends the repetitive and the inventive."16

12 In his book, The Basket Collector's Book, Lew Larason identifies this style of basket as being factory-made in the Northeastern U.S. between 1880 and 1920, which is around the same time as the mill in Grand Falls was starting up.17 Local historians believe that the first, skilled papermakers came from the United States and my research indicates there are certainly many family links to paper-making communities in Maine where the basket is still used. Millworkers in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, also use a version of the basket and although the mill in Grand Falls-Windsor is the older of the two, it could certainly be possible that the baskets became known to workers in Grand Falls-Windsor because of their use in Corner Brook. However, I believe the American connection is strong enough to conclude that the basket was imported with those first workers.

13 While I have not yet determined from where the factory made baskets were imported, the names of some of the best known local makers in the region include Angus Gunn in Grand Falls-Windsor, and Ray Osmond and Ken Payne, both of Botwood. All three men are no longer living but Clarence White in Botwood is now making baskets. Perhaps the craft is dying off because of a drop in need: at its peak the mill employed around 1 000, today it employs around 300.

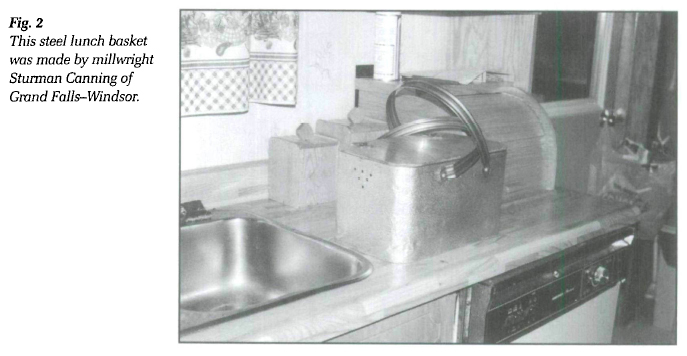

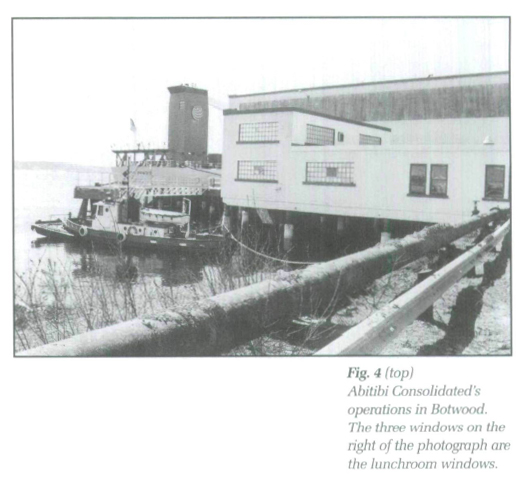

14 About a third of the workforce in Grand Falls-Windsor still carries a basket. The other two thirds use knapsacks and other kinds of bags although this practice is referred to generally as "brown-bagging it." But enter the lunchroom at Botwood where stevedores eat their lunch in between loading containers of newsprint and you will see that all the baskets waiting on the tables have been handmade (Figs. 4 and 5). On one of the days 1 dropped in, there were eighteen lunch baskets on the lunch tables. The smaller workforce there may explain this uniformity.

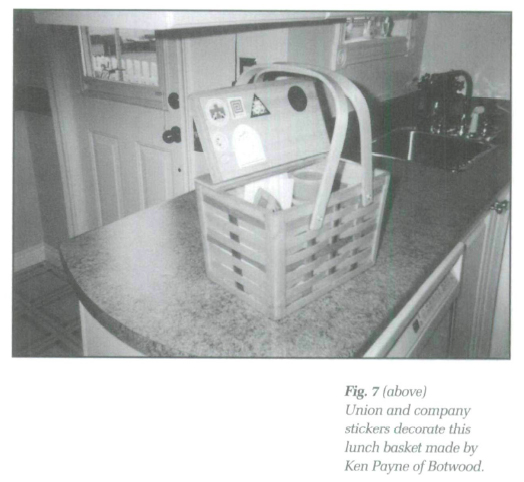

15 In A Place to Belong, Gerald Pocius wrote that some research had assumed that the introduction of new things would automatically cause social disruption.18 However, he concluded that how a group appropriates an artifact and attaches a cultural value to it becomes as revealing as the design of the artifact.19 The number of local versions of the basket that exist in Central Newfoundland indicates that the factory-made version was easily appropriated by members of the local community. My research shows there is little concern today with the origin of the basket. And although the factory-made version was for sale at a local dry goods store like the Royal Stores or the Co-Op Store, this statement from a retired millworker indicates that the locally made item was preferred:

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 6

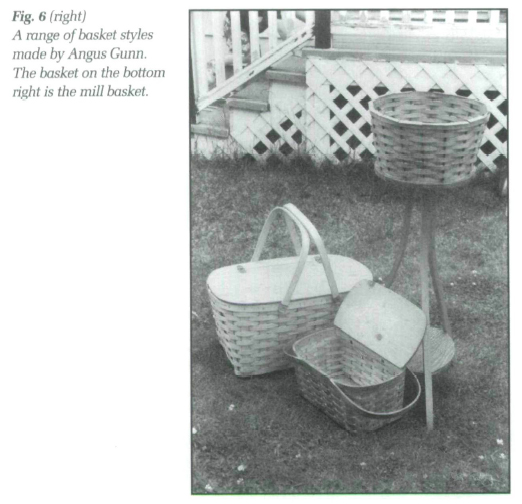

Display large image of Figure 616 Angus Gunn was born in Grand Falls in 1913. His sister and others say he made hundreds of baskets in his workshop. She can recognize his handiwork being carried by millworkers because he often placed a rim of steel around the bottom of his baskets. I asked her when he started making baskets but she did not know. Nor did she know where he got the idea to make them. The only basket she has that her brother made is a smaller version he made for her grandson in 1977. When asked, he also made a larger version as a picnic basket and a plant stand using a similar weave (Fig. 6).

17 In Grand Falls-Windsor it seems to have been important to many millworkers to have a basket made by Angus Gunn. Gunn worked as a paper maker, a member of Local 88, and he was the one asked to make the hats for the Labour Day parade. His baskets were treasured because they looked good and lasted a long time. While most of his baskets were made from birch, others were made from hockey stick handles and, as the following quote reveals, there are stories of him down at the hockey stadium keeping an eye out for broken sticks: "I used to play hockey and he used to come talking to us and wanted to know — if we broke off a stick, could we save the handle for him. Because at that time, the handles were a solid piece of wood. But now they're laminated, so you can't do the same job on them."21 Another former co-worker remembers this as well: "Mine was made by Angus Gunn. Angus made most of the baskets in Grand Falls. I worked with Angus — he worked on the old rewinder. I worked with him on number eight sulphate machine when it was running. Angus made them all by hand. It seems to me he took hockey sticks and ripped them into strips. He also cut some of his own wood."22

18 In Botwood, Ken Payne and Ray Osmond made baskets. Many of Osmond's were made from juniper and were oval in shape. His nephew recalled the kind of person Osmond was: "He was into a hobby man sort of thing anyway. He was a pretty good carpenter and I suppose he just got into it for something to do and he started making the baskets."23 Like Osmond, Payne was also well known as a carpenter. He developed a rectangular style of basket and as his son told me, eventually "dressed them up" by using a darker wood to give them a ribboned look. Today in Botwood, Clarence White is making baskets and had just sold twelve the day I stopped by in April, 2001. There are others in Grand Falls-Windsor who have made themselves a single basket: a millwright made one from steel, another man used leftover oak from making cabinets to make one and yet another made one totally from plywood.

19 I asked where people thought the first baskets had come in from. When they had an answer at all, the theory was usually expressed this way: "They probably came in from somewheres made, there are people — they seen them and when they started to break up and that, they probably started making them. And they probably made them better. Especially a Newfoundlander — he can make anything better."24 When I asked Clarence White how he learned to make baskets, he replied: "I just looked at them."25

20 In The Spirit of Folk Art, Henry Glassie writes about how folk artists learn their craft. He uses as one example, the singer Peter Flanagan: "Peter Flanagan learned as thousands of folk artists have learned. He grew, surrounded by examples of art so diverse and yet consistent that repetitive acts of imitation led him naturally into a personal version of a collective style."26 When Glassie asked weavers in Turkey how they learned to weave he could only conclude that the question itself was wrong. They learned as Peter Flanagan did, surrounded by examples and learning by "copying, repeating, receiving random hints about how to better their performance, until at last they had so mastered the art that they could control the progress of the rug."27 He uses as a final example, the basket maker, William Houck: "William Houck, basket maker from upstate New York, did not remember being taught. His father was a basket maker, but as Mr Houck said, 'I just figured it out by myself.' Watching others at work, looking at examples he admired, Bill Houck taught himself to fit into the old Adirondack style."28 Glassie concludes: "They all learned the same way. They were born into environments that supplied them with models that they copied, botched, copied and improved. Eventually they had so mastered the style implied by their models that they developed a personal version of a tradition that had embraced them from birth."29 It seems likely that the basket makers in Central Newfoundland also learned their trade by example, by looking, by figuring it out for themselves.

21 Many workers kept their father's basket, which may have been passed on to them. Again, in The Spirit of Folk Art, Glassie writes about why we keep things: "We accumulate souvenirs...to relive the past. Treasuring artifacts that remind us of people we knew and loved, collecting things we associate with ways of life we would like to see perpetuated, things that can be sources of nourishment for the creative spirit in a new age. A way to preserve the past for use in the future. They provide thinkers with tools to use in contemplating life."30 Collecting is one of the means people use to connect themselves with the past. A millworker explains why he kept his father's basket although he no longer uses it:

22 The basket represents its owner because he has personalised it, through both decoration and use. In some cases, workers have personalised their baskets with their children's school photographs, with union stickers, and their work schedules, clearly using the basket to link home and work. As one current millworker told me, by the time a millworker retires, he has made his basket into his own creation:

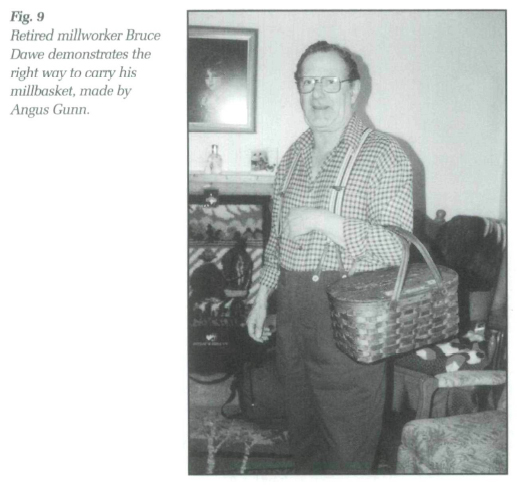

23 As the above description indicates, there are many layers to the basket's life. Made by a local person like Angus Gunn or Ken Payne, the basket is remade by the millworker who carries it to work (Figs. 7 and 8).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8Women's Domestic Work

24 While at first glance the basket may be seen as an artifact made by men for men's use, it is an excellent example of how material culture allows us to probe the often neglected area of women's domestic work and its links with men's paid labour. The basket is the woman's responsibility as soon as the man brings it into the home. A daughter's words illustrate her awareness of this gendered division of work: "Every night he comes home and he puts his basket on the counter and Mom takes out the dishes and stuff and in the morning Mom fills it with whatever he needs and leaves it on the top of the stairs and he just takes it as he leaves. It's kind of a ritual."33 And a son pondered this division during our interview:

25 As the above quotation indicates, packing the basket was a major priority in the home. It was always a focus of women's domestic work, as they prepared one meal at the same time as they were planning the next one. One woman described how her mother prepared her father's lunch basket: "It's usually leftovers from the night before. When Mom takes up supper, it's always — she takes up our plates for supper and then Dad's dish for the next day and his lunch box. So there was always enough cooked. So there was ours, and then Dad's lunch. So you couldn't go back for seconds till Dad's lunch was taken up."35 Another woman told me: "We'd just tidy away from a meal and I'd say 'Oh my God, I haven't got your lunch ready yet.' And I had to turn around and get the lunch ready so, I mean, it was a busy time for me. All he had to do was pick up a basket and go to work. But I mean, I had to cook the meals home. And it was always a cooked meal. Cause it was only twice he took sandwiches to the mill. Only twice in all them years! So he was well fed!"36 Pride is evident in her words when she told me that her husband only took sandwiches instead of a full meal to work twice in thirty-eight years. She listed to me the things she had sent in: "Macaroni and cheese. And cooked vegetables and chicken. And turkey. And beef. Pork chops. Always with the trimmings — everything to go with it. It all went into this casserole bowl. Then he'd have his bread and jelly and fruit and cookies—or any kind of dessert that I had in the house. And his bottle of milk of course. That had to go in every basket."37 Another woman told me her father considered it a "rip off when he got sandwiches, even though he got a whole loaf of sandwiches. He preferred a hot meal. Remarking on the amount of food that was sent in, she said: "They eat like horses down there. It's really quite frightening. I'm surprised they're not all dead of heart attacks a long time ago 'cause of what was in those baskets."38

26 In her classic study of three generations of women's domestic work in Flin Flon, Manitoba, Meg Luxton describes this type of work as "more than a labour of love," refuting the notion that, because women's domestic work is based in the private world of the family, it is merely a "a labour of love."39 Luxton identified food preparation as one of the most time consuming tasks in a woman's work day.40 One of the components of food preparation that Luxton identified is the need to ensure that all the equipment and supplies needed for a particular task are available. For many of the women Luxton interviewed, this was one element of their work which they considered onerous. The same situation can be observed in Grand Falls-Windsor where shiftwork and unexpected overtime required that extra food always had to be available. As one woman told me: "You had to be a step ahead of them all the time. And if he got called in on an extra shift, you had to be prepared at the drop of a hat to accommodate that. You're talking about a picnic basket full of food."41 The regulation of industrial work life, as exemplified by the whistle, was felt at home as well as at the mill. Just as with men's, women's lives were regulated by the mill whistle as they worked around their husband's, and often sons', shiftwork, planning and preparing meals. One woman said: "Back then, we all worked by the whistle. The women worked by the whistle too. The whistle blew at seven. You had to be up then, making the man his breakfast. It was a rush. You didn't stop much. The kids worked by the whistle too because they were off school at twelve and had to go back at one. Sometimes you'd have the lunch packed in the basket and one of the kids would take it to the mill. You had to get supper on the table when the whistle blew."42 Women describe shiftwork as particularly hectic, as a number of tasks must be performed at the same time. One woman told me about the difficulties of trying to fix breakfast for her husband who had just got off a shift and trying to get the children off to school, and, as Luxton labeled it, the "endless duty" of getting one meal over with while planning the next.43

27 The women who prepared these meals were no doubt aware that their husbands' and sons' coworkers would observe the quality of the meals that were sent in. Anne Allison's article on the Japanese lunch box provides an example of how preparing food in certain cultures follows social constraints, as those who prepare it are socialised into preparing a meal "the right way." In her article, "Japanese Mothers and Obentôs: the Lunch-Box as Ideological State Apparatus," Allison writes about food as a cultural and aesthetic apparatus in Japan, where it is "endowed with ideological and gendered meaning."44 This informal message is also seen in Grand Falls-Windsor, where what a man brought in was definitely noticed by his coworkers. As the following description from a retired millworker indicates, sometimes a man's income was judged by what he brought in: "Some people would have fabulous meals, some more people would have mediocre meals, depending on your income and your family lifestyle. You couldn't help but notice what everybody had for their meal. You could determine who had the good meals and the not so good meals. Sometimes my meals weren't great, cause there were eleven of us in the family. We had tough times. She had to send in three meals and she had six kids home from school. Every apple and orange counted."45 Another woman was embarrassed by what her husband, in contrast to her father, brought in for his meals:

28 Her discomfort emphasizes the pressure some women in the community feel about preparing a meal the "right way," the way that was accepted by the other millworkers.

29 People in Grand Falls-Windsor remark on the closeness of millworkers, noting that if you wanted to know what was going on around town, you only had to ask a millworker because: "he knew what was going on before it happened."47 But for many women, domestic work was isolating and lacking the camaraderie of the mill. One woman contrasted her father's life with her mother's when she said: "The life that my Mom lived was totally separate from the mill. That was Dad's world. All she did was feed it — and she did that a lot."48 The deliberate separation of men and women's work is characteristic of women's work in industrialised communities and Grand Falls-Windsor is no exception. Grand Falls was a closed company town until the 1960s and the A.N.D. Company had established a pattern of paternalism as families lived in company housing, participated in company sponsored activities and purchased goods from the company store.49 In a recent study, Ingrid Botting noted the early goals of those who started the community: "The A.N.D. Company sought to transform a disparate group of workers, as well as their wives and children, into citizens of an industrial town. Part and parcel of that transformation was the dominance of the gender ideology of the male breadwinner and female domesticity."50 As this discussion indicates, one of the prime responsibilities for women was the preparation of meals for the male breadwinner.

30 Certainly, the food that was sent in provided comfort, nourishment and a touch of home to those working in a hot, noisy mill. A mother's care is evident in the following description: "When you worked in the mill, you sure got fed. Because your mother knew you were working really hard in there. You're really working, so they really packed a lunch. I remember a friend opening his lunch one day and saying, 'Does Mom think I'm never coming home?!'"51

Rites of Passage

31 Some of the meals that were sent into the mill were shared amongst workers and today it is not uncommon for a group to cook up a meal together in the mill itself. Arnold Van Gennep identified the rite of eating and drinking together as clearly a rite of incorporation.52 In his famous work, The Rites of Passage, Van Gennep delineated three stages to the rites of passage that accompany life changes. He identified the rites of separation, rites of transition (initiation), and rites of incorporation.53 At the mill in Grand Falls-Windsor, new workers are initiated into an unfamiliar workplace through the playing of pranks, incorporated into a new status through the receipt of a millbasket, and separated from work through retirement.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 932 Van Gennep wrote about the importance of the doorway as a marker of a new world. He wrote: "The door is the boundary between the foreign and domestic worlds in the case of an ordinary dwelling, between the profane and sacred worlds in the case of a temple. Therefore to cross the threshold is to unite onself with a new world."54 While neither a temple nor a home, the mill is a place of heat, noise and mystery to the uninitiated. Some residents use religious imagery when speaking about the mill, as this one woman did when she gave me her first impressions of the mill:

33 In the case above, children gained entry to the mill through an organised tour and under the guidance of an experienced worker. Other children got close to the mill when they delivered the packed lunch basket. Proudly carrying the basket in a manner that imitated how their fathers' would carry it, they made it only to the inside of the "punch office" where they could lay the basket down on one of two benches. As one man told me: "You would walk down proudly with your arm up like this and the basket kinda hanging by your side. You put on the act as if you were a millworker"56 (Figs. 9 and 10). Some children earned small change for delivering lunch baskets. For others, it was reward enough just to get close to the mill and to be able to see their father: "That was a real treat — to see them coming through that big dark hole at the end of the tunnel thing."57 For those not yet allowed in, there is a sense of being at the doorway of something mysterious: "[When delivering the lunches] we got to go inside the mill. I mean — this monster down the end of the road, that we could see from our house — the smoke billowing out — it was a mystery what was inside. We were never permitted — I think I was sixteen, seventeen before I got through the doors there. So, we didn't know what went on inside the mill. It was sort of like a secret. But we got to bridge that just at the door — to get in there a little ways at times. So that was exciting enough for us. The fact that we had an opportunity to go down was often payment enough, right."58 The speaker is conscious of being at the door to something he was restricted from comprehending.

34 Van Gennep has identified the initiation stage as one of "wavering between two worlds": "Whoever passes from one to the other finds himself physically and magico-religiously in a special situation for a certain length of time: he wavers between two worlds. It is this situation which I have designated a transition, and one of the purposes of this book is to demonstrate that this symbolic and spatial area of transition may be found in more or less pronounced form in all the ceremonies which accompany the passage from one social and magico-religious to another."59 The new worker wavers between two worlds and requires someone to show him around, to initiate him into this new world. As one worker said: "I never went in to the mill, outside of the punch office, until I got a job. Someone had to show you what to do."60 Included in the initiation stage are pranks and jokes that teach the new worker about the work site itself, the personalities of other workers and the operation of machinery. For, as Robert McCarl has pointed out: "in spite of what new workers think they know, there are traditional ways of doing things in the workplace which workers themselves create, evaluate and protect."61 The stories I was told about first day on the job contained the classic elements of being sent for greased lightning62 and having to ask the crankiest men on the job for directions.63 One man spoke of being sent to the basement: "I remember going down to this basement, spooky as Dickens, mile after mile of aisles. And noises. And being set up in terms of ghost stories from the guys."64

35 In her study of the occupational narratives of pulp and paper millworkers in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, Contessa Small has suggested that the goal of this kind of prank is to give the new worker familiarity with a new workplace.65 In addition, workers in dangerous, hot, and noisy industrial plants must rely on each other for safety. Management warns about safety through official signage such as notices on bulletin boards throughout the mill. But as Small illustrates, informal communication about safety amongst workers is also extremely important. Worries over being able to rely on a coworker and his attention to his job are frequently expressed and enacted through pranks. Lazy people, particularly those who fall asleep on the job, are often targeted. Cigarettes were dropped down the pants of sleeping workers or water was sprayed on them. In one elaborate prank, a mannequin was set up: "There was one guy they didn't get along with too well. Anyway, he fell asleep on a shift. So they made this dummy and hung him from a rafter. Then they made noise. Course — he woke up. And when he woke up, there was this — he thought that the guy he was working with on that shift, was after hanging himself. So they're always up to stuff like that."66

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1036 Pranks were also played on workers who were too eager to leave, this time using the basket in the prank: "You'd have your basket on the table and you'd have your shower and you'd be getting ready to go home. You'd come out and you'd grab your basket, when the whistle would blow or whatever — and they'd nail your basket down. You'd haul the handles off your basket! Or they'd fill it full of rocks or something like that."67

37 For some in Grand Falls-Windsor, a job at the mill was a good opportunity. For others, worried about industrial disease such as deafness and accidents like losing a limb, the mill was not always thought of as the best place to work. One resident described this attitude as: "it's like mining towns where the father always says: 'well, the young fella's not coming in here to work.'"68 Nevertheless, fathers could ensure their sons a job at the mill. One of the ways of incorporating a son into this new status was by passing on a lunch basket. One woman told me how common this was: "Normally, most guys, there's someone waiting in the wings. 'I want Pop's basket, or Dad's basket' or whatever. That's a big deal. Which it is. I know for my brother-in-law it is. Meant a lot to him especially when his grandfather passed away. He treasures that."69

38 Getting a basket was also a way of marking a new status, the status of a permanent job. One of the most striking symbolic uses of the basket as an indication of the ceremonial in everyday life is as a marker to this new status. A number of people I spoke with talked about the basket as being a sign of a permanent job: "It's a symbol that you are a millworker. To be a millworker was an honourable profession and it's still considered an honourable profession. It's good work. It's hard work. It's hard to dedicate yourself to forty years of working in a factory. It [the basket] sort of tells everybody — look, I'm a steady guy. I work every day of my life. There's certain things that you can know about me by the fact that I'm carrying this basket. You know that I have a good job and a well paying job. You know that I show up for work on a regular basis."70 This linking of the basket with the identity of the male worker was particularly emotional to one woman: "The basket is a status symbol of: I've got a permanent job in the mill. Here's my basket. Because first when my husband passed away, I found it very hard to see the men in the mill with their baskets. I used to make sure I was in my office so I didn't see the men going out with their baskets. It's just, that picture is there: the man and his basket, the mill and his job."71

39 With the mill now equipped with lunchrooms and microwave ovens, meals are sometimes cooked communally. One daughter described what her father made in the mill and concluded: "They ate like kings — they ate better in the mill than they did at home."72 For many millworkers, eating meals together is a form of bonding. As one millworker told me, the strengthening of this connection between millworkers can be seen in the sharing of meals:

40 For this speaker, the concept of the lunchroom developed directly from the lunch basket and the right to have uninterrupted time to eat.

41 As the worker retires, he separates from his former coworkers and the workplace. This is often recognized formally through a retirement party, which is a well-established ritual of separation.74 For one millworker who had no son to pass his basket on to, jumping on his basket at his retirement party broke not only his own link to the mill but also his family's:

42 The speaker energetically participated in his transition from active millworker to retiree by destroying the artifact that identified him as a millworker: his lunch basket.

Conclusion

43 In Central Newfoundland, an artifact introduced as an imported, factory-made artifact has become accepted as a means of identifying someone who works in the local industry and as a symbol of a "permanent job." While individual basket makers like Angus Gunn, Ray Osmond and Ken Payne are recognized for their skill in making baskets, the baskets are remade by their owners through daily use as well as embellishment. Delivering the basket to the mill allowed children the chance to stand at the threshold of a restricted world, into which new workers are initiated through customary behaviours like pranks. And while the basket links home and work by bringing food and comfort to the mill, it also separates these spheres by highlighting the gendered division of labour imposed by industrial work. While its use may be decreasing, to many in the region it is an absolute marker of a millworker. As one woman told me: "To us it's — he's supposed to have a basket. You see a guy coming out on shift and all the workers are coming out, and he doesn't have a basket — you almost feel like shouting — 'hey, you forgot your basket!' It really looks strange if they don't have it."76

I would like to thank all the people in Central Newfoundland who have given me their time over the last five years during both my museum and dissertation field work. I thank Dr Gerald Pocius, Dr Pauline Greenhill, Dr Diane Tye and Caitlin Peeling for their suggestions regarding this article. My research has been generously supported by a Ph.D. Fellowship and research grants from the Institute of Social and Economic Research at Memorial University of Newfoundland.