Articles

"As the Locusts in Egypt Gathered Crops":

Hooked Mat Mania and Cross-Border Shopping in the Early Twentieth Century

Abstract

The hooked mat, a domestic craft product originating in northeastern Canada and the United States in the mid-1800s, enjoyed a revival in the 1920s that journalists dubbed "hook mat mania." In an expression of antimodernist sentiment, affluent urban Americans acquired handicrafts made by "simple" rural folk, eventually realizing large profits through resale when the mats gained mass popularity. This paper explores the impact of the "mania" on Nova Scotians from a social, cultural, and economic perspective. Collectors, dealers, and handicraft organizers transformed these domestic floorings into consumer commodities, severed from their primary function, social context, and provenance. Ironically, without outside attention, little record would remain of this craft tradition. Furthermore, the consumer impulse allowed rural women to contribute significantly to the family economy during hard times.

Résumé

La carpette crochetée, produit domestique artisanal apparu dans le nord-est du Canada et des États-Unis au milieu du XX siècle, a connu dans les années 1920 un regain de popularité que les journalistes ont appelé « folie des tapis au crochet ». Dans leur volonté d'exprimer leur antimodernisme, les citadins américains aisés achetaient des produits artisanaux fabriqués par les gens « simples » de la campagne et ont fait de gros bénéfices en revendant ces tapis quand ils sont devenus populaires. Cet article étudie les répercussions sociales, culturelles et économiques de cette «folie » sur les habitants de la Nouvelle-Ecosse. Collectionneurs, vendeurs et organisateurs d'expositions d'artisanat ont transformé ces couvre-sol d'usage domestique en produits de consommation n'ayant plus rien à voir avec leur fonction première, leur contexte social et leur provenance. Ironiquement, si le public ne s'était pas intéressé à cette tradition artisanale, il resterait peu d'information à son sujet. La demande a en outre permis aux campagnardes de contribuer de façon marquée à l'économie familiale en période difficile.

1 In the closing years of the twentieth century the Nova Scotia Museum participated in an unusual instance of cross-border shopping, purchasing a hooked runner that had crossed the border in a southerly direction in the early 1900s. This act of repatriation was significant both materially and symbolically. Unlike most hooked mats1 that travelled to the United States and changed hands often through auctions and antique sales, this particular runner had remained in one family for at least seven decades. Its pedigree was enhanced by the fact that the owner had been none other than William Winthrop Kent, a noted collector whose articles and books on hooked rugs during the 1930s and 1940s even today remain important reference works on the subject. A photograph of the runner with a caption identifying it as Nova Scotian appeared in Kent's first publication, The Hooked Rug.2

2 Although the maker(s) and specific history of this hooked runner remain unknown, that Kent could name Nova Scotia as the place of provenance may have been sheer happenstance. Most of the hundreds of thousands of hooked mats that left the province in the early years lost their Nova Scotian identity. Cross-border identity loss for Nova Scotian antiques has always been difficult to gauge or prove conclusively. However, another recent cross-border shopping excursion (via the internet) led to the discovery of an American source from the period which acknowledged this trend. The accompanying essay in the 1923 catalogue of a New York sale of hooked rugs "entirely of Nova Scotian origin" stated that:

3 The Kent runner, a geometric with maple leaf design, twelve feet (3.6 metres) long by four feet (1.2 metres) wide and constructed of rags dyed in rich autumn and dark brown shades, is an impressive piece in its own right. However, as a token repatriation, its primary purpose at this point is symbolic. It becomes a commemorative to all the hooked mats forever lost to the province. Lest we become too teary-eyed and sentimental, though, it might be useful to remember the museum's participation in an ongoing process. In its various travels across borders and time, the runner's purpose, sociocultural meaning, and value have been and continue to be transformed.

4 To understand the mass exodus of hooked rugs from the province and how the meaning of these cultural artifacts has shifted, one must retrace the history of rug hooking, both real and imagined. While there has been considerable debate on the origins of the hooked rug, contemporary scholars agree that this form of rug making originated sometime during the second quarter of the nineteenth century in the Maritimes and New England. Initially, hooked rugs were made on a linen ground with homespun wool, implying an intensity of labour and material resources well beyond subsistence living. Rug hooking became far more widespread with the introduction of burlap to North America in the 1850s. The looser weave of the ground fabric made hooking easier and faster. As well, recycled feed bags provided essentially free material for those who could not afford to buy foundation cloth. The development of the North American textile industry, which lowered the cost of fabric further, helped to democratize access to manufactured cloth. Now required to spend less time in primary production of household textiles, many women, especially in rural areas, turned their attention to making quilts and hooked rugs by recycling used clothing and bedding. In comparison with weaving, the tools and equipment required for rug hooking and quilting were simpler and more portable.

5 As an expression of Victorian domesticity, rug hooking allowed women to create both decorative and practical floor coverings with little financial outlay at a time when relatively few had the cash to purchase manufactured or imported carpets. As well, in the Maritimes, at least, rural women used mat hooking as an opportunity to socialize. Matting parties, like quiltings, brought relatives and neighbours together and in some areas of Nova Scotia, this tradition persisted (albeit on a much-reduced scale) well into the mid-twentieth century.

6 Though rug hooking originated as a domestic and, hence, primarily female-gendered undertaking, business-minded individuals, usually male, soon recognized the commercial potential in the craft and began producing patterns stamped on burlap.4 Prior to this development women created their own patterns, borrowed from local design traditions or copied from other needlework sources. Either they or some member of the family or community would draw a pattern directly on the burlap canvas. These traditions continued, but stamped patterns opened up a large new market. Among the several commercial pattern makers to emerge, two of the most successful were Edward Sands Frost of Biddeford, Maine, and John E. Garrett of New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. Frost began in the late 1860s and sold his successful business less than ten years later. Garrett (whose company lasted for eighty years) started in 1892 and opened a second branch in Boston in 1900.5

7 By the turn of the twentieth century, rug hooking was still common in rural areas, but increasingly, families with any spare cash were purchasing ready-made carpets and linoleum, often through the mail-order catalogues of T. Eaton's in Canada and Sears Roebuck in the United States. The idea of rug hooking as a particularly nineteenth-century craft is communicated in Garrett's ad for the 8 August 1900 edition of The Family Herald and Weekly Star, Canada's national farm paper. "I make patterns for old fashioned [my italics], home made hooked rugs" proclaimed the advertiser, indicating, perhaps, an awareness or premonition that appeal to nostalgia might be a good sales pitch.

8 Garrett, whether knowingly or not, was anticipating future trends. The irony, of course, was that at the same time as many ordinary folk were finally in the position to cast away their "old fashioned" hooked mats in favour of more modern floor coverings, wealthy Americans were beginning to desire such objects. Several social and cultural phenomena contributed to this trend. The arts and crafts movement, first-wave feminism, social and religious reform impulses, and tourism all played their roles. In North America, in particular, women were primarily responsible for the spread of arts and crafts ideals. As a result of the late nineteenth-century feminist movement, a growing number of women entered post-secondary education and fields of endeavour previously denied them. In the United States, art and design school graduates like Candace Wheeler and Helen Albee saw handicraft renewal as an ideal way for creative designers to practice their profession at the same time as providing moral and economic uplift to impoverished rural women. In Canada, women such as Alice Peck and Mary Phillips, the founders of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, promoted the arts and crafts ideals within the particular Canadian context.

9 If rug hooking did not initially register in the list of preferred crafts in the arts and crafts movement, it finally won recognition because designers learned that it was easier to implement their home industry programs using the existing craft skills of a local population. Not all efforts met with enduring success.6 Nevertheless, a growing market for hooked mats encouraged attempts in various locales. Missionary initiatives also combined with the craft impulse to create fireside industries. One of the most famous and long lived of the hooked mat industries was founded by medical missionary Sir Wilfred Grenfell in Labrador.

10 Nova Scotians were relatively late in receiving the attention of fireside organizers, missionary or otherwise, but their mats were not ignored. The earliest mats left the province with little notice or fanfare under the arms of American summer visitors. Long before the provincial government took an active role in tourism promotion, Nova Scotia was on the traveller's map. Between the 1850s and 1900, American writers such as Frederic Cozzens, Charles Dudley Warner, and Margaret Warner Morley helped to publicize the rustic charms of the province.7 Literature abounded for hunters and fishermen who sought out the woods and streams of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland for their sport. Railway and steamship lines published pictorial essays to entice customers to their businesses.

11 In a travelogue written ca 1895 for the Dominion Atlantic Railway by Charles G. D. Roberts, a well-known Canadian writer of the period, Digby, a town on the Bay of Fundy, is described as "a veritable Sleeping Beauty until June brings the summer tourist to caress her into activity." This "Brighton of Nova Scotia" according to another travel guide of the same period listed ten hotels and boarding houses, accommodating more tourists than any other place in the province outside of the capital city of Halifax.8 As will become evident, it is not surprising that by the time "hooked rug mania" hit the American public in the 1920s, Digby had become a centre for the hooked mat trade.

12 In addition to the hotel sojourners, a growing number of urban Americans with means sought out waterfront properties at various locations along Nova Scotia's coastline where they built vacation homes. They began to furnish their "cottages" with rugs collected from the surrounding countryside.9 For example, in 1900, American geologist John Porter and his wife Ethel purchased a summer home in Guysborough, Nova Scotia. Appointed the first chair of the geology department in the late 1890s at McGill University, Porter discovered Nova Scotia while carrying out investigative work on mines for the provincial government. According to the grandson who inherited the house with its extensive collection of hooked mats, the Porters acquired their mats in the local area by knocking on farmhouse doors.10

13 This mode of gathering mats is confirmed by other travel writers and collectors of the period. Ruth Kedzie Wood, in her 1915 travelogue The Tourist's Maritime Provinces, recounted a visit to the home of the Desveaux family in the Acadian community of Chéticamp, Cape Breton. She described the living room as "carpeted with red-scrolled and gorgeously bouqueted hooked rugs." She stated:

As Wood tells the story, one would gather that Chéticamp hospitality included giving away household items to travelling strangers. It is impossible to know whether this was a spontaneous action on the part of the Desveaux family, or whether there had been a hint or request for these items from the traveller.

14 Wood was ostensibly a travel writer who acquired at least one mat (perhaps more) on her journey. The Porters and others like them who regularly summered in Nova Scotia had many opportunities to build their collections gradually. However, there existed another kind of collector, whose chief purpose in travelling focused on the hunt for hooked rugs. And hunt they did. It is notable that in the accounts of collectors the language used to describe "rug hunting" sounded much like the language of game hunters. The Maritimes presented a prime hunting ground for rug collectors and the voraciousness with which they pursued their "prey" accounts for the relative dearth of older examples in the provinces today.

15 William Winthrop Kent, American architect and former owner of the Nova Scotia Museum's recently acquired hooked runner, provides one such commentary. In The Hooked Rug he described a brief foray into New Brunswick, in a chapter titled "A Hunt for Rugs in Canada." He set himself the challenge of seeing how many rugs could be found in a day, just by knocking on farmhouse doors in an area that had not been scoured already by earlier rug hunters. By dusk, the tally was a "slightly groaning" carload of thirteen or fourteen rugs.12

16 The 1927 publication Collecting Hooked Rugs, written by intrepid collectors Elizabeth Waugh and Edith Foley, also used the language of the hunt.

When encountering rug owners who would not part with their rugs, these collectors seemed to think the owners' sense of attachment to their personal possessions unreasonable. "One frequently finds a complete unwillingness to part with hooked rugs at any price, even though they may be serving no other purpose than that of kitchen mats."14

17 Apparent in much of the writing of the time was the presumption by collectors that money and privilege allowed them to travel and enjoy the hospitality of "simple" country folk and then leave with their hosts' family heirlooms. Waugh and Foley express this truth with no compunction in the last sentence of their book:

18 It is true that the rural areas of the Maritimes were out of the mainstream of urbanized America; however, travellers and rug hunters often chose to assume that all country folk were simple, primitive souls who had little awareness of the outside world. In point of fact, newspapers such as the Family Herald and Weekly Star kept rural readers abreast of national and international news. As well, out-migration for work and educational opportunities was so widespread that few families in the region were untouched by this trend.

19 The 1924 correspondence of one rug hooker who produced work for Grace Helen Mowat, New Brunswick's most famous organizer of cottage industry, gives a humorous and insightful view of one of the "simple" folk. In describing her enjoyment of rug hooking, she says,

It may be unfair to compare the above writer, Stella Surette, with the older, traditional hookers that Kent, Waugh, and Foley might have encountered on their rug-hunting safaris, for she was consciously producing for the hooked rug market, which by that time was considerable. However, it is unlikely that buyers seeking to satisfy their ravenous appetite for rugs (antique or otherwise) would attribute such cosmopolitan awareness to a rural rug hooker from the Maritimes.

20 As mentioned earlier, pattern maker John Garrett seemed adept at anticipating and taking advantage of market trends. In 1920, Garrett alerted Canadian readers to the revived popularity of hooked rugs.

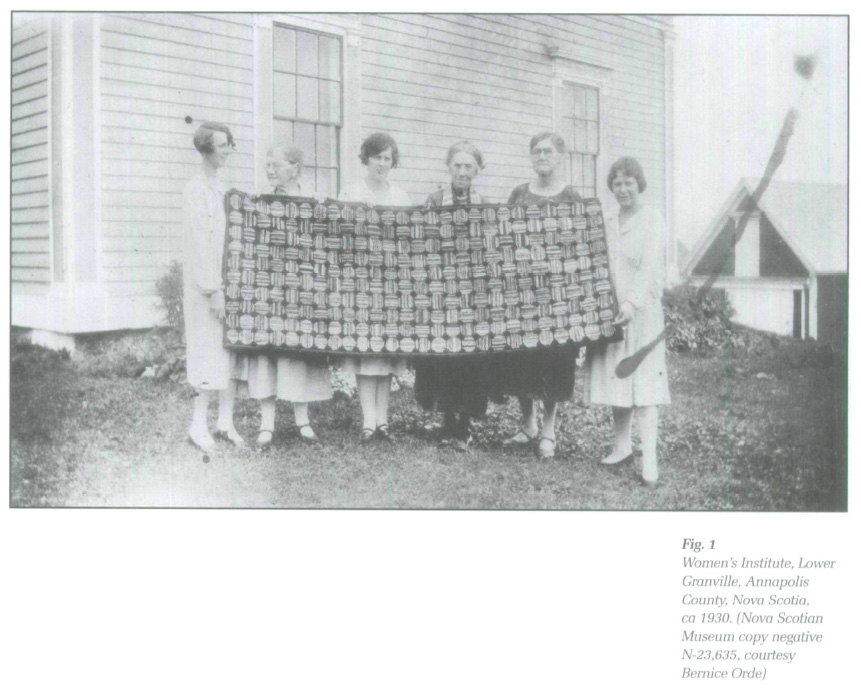

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 121 Several crucial factors contributed to the unprecedented appeal of hooked mats in the 1920s. In an increasingly urbanized and consumerist America in which citizens were one or more générations removed from domestic production of household goods, nostalgia for "old-fashioned" home-made items created a new niche in the marketplace. In the flurry of interior decorating interest in colonial furnishings, hooked mats were promoted in magazine and newspaper articles as ideal additions to room settings. The rare commentator who suggested a more historically accurate assessment of the age of hooked rugs found few receptive ears; for the most part, romanticism triumphed. Understandably, dealers, auctioneers and others who profited from brisk sales found little reason to debunk the hooked mat mythology.

22 It would he incorrect to say that everyone assumed their hooked rugs were antiques. While those with money could purchase the older examples (Victorian, rather than colonial), most buyers satisfied themselves with newer rugs. The craze for hooked mats stimulated production, both in Canada and the United States, again, particularly in areas where designer/social workers thought that local populations might benefit economically from the work. Not surprisingly, by the time hooked mats gained widespread popularity, the earlier collectors and trend-setters were beginning to sell off their amassed collections for considerable sums. From 1921 onwards, the New York Times began to carry announcements and reports on sales and auctions of large collections of hooked rugs accumulated by those astute buyers who had entered the field well in advance of the rest of the public.

23 Aside from the summer visitors and those determined rug hunters such as Kent, Waugh, and Foley, the number of collectors who would have travelled the country roads of the Maritimes to collect directly from householders was probably quite limited. Shrewd itinerant peddlers recognized the emerging market and were well positioned to become intermediaries in the trade. Familiar with farmhouses throughout their circuits, they offered linoleum and other goods to cash-poor rural women in exchange for hooked mats. Consequently, money made in Nova Scotia from the sale of hooked mats generally went to peddlers and dealers rather than rug makers.

24 This trend predominated for years; however, once women recognized the popularity of their craft and as the supply of older mats began to wane, rug hookers began producing specifically for the market rather than just for home use. Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources, recognizing that the economic potential of hooked mats dovetailed nicely with its developing tourism thrust, published an article titled "Money in Rugs" in 1927. Appearing in newspapers around the province, the article urged women to get into market.18 As well, the Women's Institute, operating under the Department of Agriculture, promoted hooked rug production through exhibitions, publication of a "how-to" manual, and setting up Women's Handicraft Exchanges at strategic tourist locations throughout the province.

25 As mentioned earlier, the Digby area on the Bay of Fundy was a popular spot for summer vacationers. An article appearing in the Halifax Daily News on 1 January 1929 attests to the volume of trade and export out of Digby. The report stated that one local antique dealer had shipped more than 20 000 rugs to Boston during the previous year, and that he was only one of several buyers doing business in Digby.19 A 1931 Montreal newspaper article reported that during the year "one firm alone bought about 50 000 mats in Nova Scotia. It went on to say that mats were bought up in such large numbers by American tourists that "women [were] busy with their fingers preparing for another season."20 As an early reader of this paper has rightly suggested, one must exercise caution in accepting wholesale the numbers that newspaper accounts of the period put forward. Given that the Great Depression was well underway and the "requirement of media in Nova Scotia to do some 'positive thinking' in truly desperate times," it would not be surprising to see overblown figures to boost local morale and encourage craftworkers to greater labours.21 Nevertheless, evidence from other oral and written sources of the time indicate that such numbers are not entirely without substance. Because the historic trend has been to under represent in public accounts women's domestic production, such numbers at first glance seem extraordinary. Yet, research into records of volunteer production of quilts and other textile goods for wartime and inter-war relief indicate similarly remarkable output.22 As well, it must be remembered that the figures reflect not only hooked mats made specifically for the marketplace but also those culled from households throughout the countryside. In spite of the rug hunting in preceding years, hooked mats still graced the floors of many homes in the province. While rug hookers continued to produce for home use as well as for the market, the supply was not static. New rugs were made to take the place of worn (or traded) ones.23

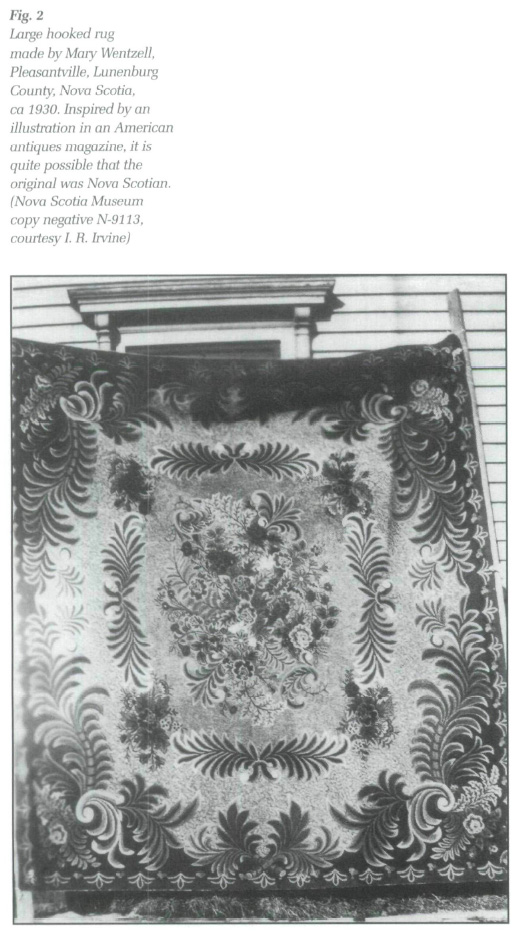

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 226 The Nova Scotia government departments involved in encouraging the home industry discontinued their initiatives due to perceived falling markets; however, mat production and sales continued throughout the 1930s. Concerned about the economic plight of local constituents, in 1932, B. C. Mullins, Secretary-Treasurer of Gloucester County, New Brunswick, wrote to the federal Ministry of Trade and Commerce seeking help with direct marketing of hooked mats from the region. Aware of an upswing in the business over the "last two years" and referring to the dealers scouring the province, he wrote:

Two newspaper advertisements in a 1934 edition of the Boston Globe show that Maritime mats were still on the market in high volumes and illustrate the retailers' understanding of hooked mat appeal. The Chandler & Co. advertisement declared, "Sale! Hundreds of Antique and Semi Antique Hooked Rugs.. .real old-fashioned type made up by the people of the Canadian provinces for their own homes." "These New, Clean Hand-Made, Canadian Hooked Rugs present rare gift values!" trumpeted the T. D. Whitney Company.25

27 The production of hooked mats helped to pull many rural families through this difficult time. In adversity, the gendered division of labour lost some of its rigidity. Men and children, both girls and boys, joined in the work, particularly with some of the very large room-sized rugs that became popular with those who could afford them. For a small number of men in Chéticamp, rug hooking provided both monetary and creative satisfaction and they continued in the industry as full time permanent workers even after the Depression.26

28 Estella Withers, a widow in Granville Centre, Annapolis County, paid off the mortgage on her farm and helped support herself through hooked rug sales. The 1933 newspaper account of her story contains a rare and invaluable record of her work and earnings:

In order to understand the economic impact of rug hooking, it is useful to compare Estella Withers' earnings with the Labour Gazette figures for male agricultural workers over the same three year period. Withers made over $1000 at the same time as male farm workers earned just over $1200, including room and board. Wages alone were less than $900.28

29 Rather than calculating value according to hours of production labour, hooked mats were assessed by the square foot.29 Based on a rough calculation of Withers' output, it seems likely that she was making no more than 75 cents per square foot (.1 square metre) and, possibly, considerably less. The previously-mentioned Montreal newspaper article suggested that the average price paid for a rug was $2.50. For even the most modest-sized mats (two by two or three feet) (.6 x .6 or .9 metres), this only translated into forty to sixty cents per square foot. One example cited, of a 12 by 12 foot (3.7 x 3.7 metre) rug made ca 1897, commanded a price of $160.30 Prices differed according to such variables as quality of hooking material (mats made from wool yarn or wool rag commanded better prices than those made with cotton, which had less durability); colouring (natural or synthetic dyes); design (original or commercial pattern); age (antique versus new); and size (room-sized hooked carpets generally commanded better prices per square foot). One informant from Colchester County who talked of dealers and itinerant trades people commissioning rugs in her area during the 1930s said that "men, women and everyone" would receive "the big sum of one hundred dollars" for a "nine by twelve rug," which meant they were receiving a handsome ninety-two cents per square foot.31 Mary Wentzell of Lunenburg County was one of the rare rug hookers who enjoyed a high profile as an individual craftworker in the field. Reports of prices exceeding $1000 for her large room-sized hooked carpets placed Wentzell's work in a class of its own.32 Nevertheless, even in Wentzell's case, the real profit for her work went to others. One of her rugs bought by an American was purportedly resold to Henry Ford for $4500.33

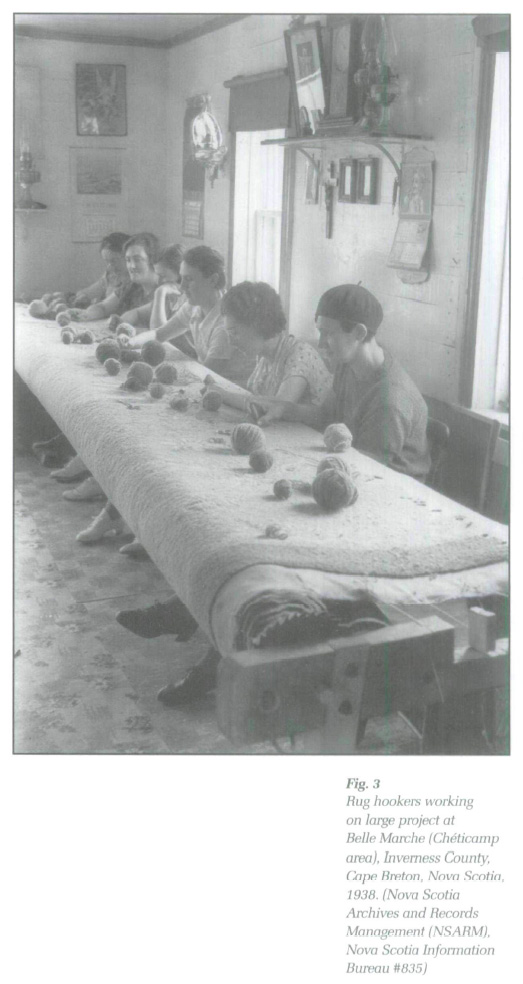

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 330 While this paper cannot do full justice to the story of the Chéticamp rug industry, it is useful to note that the famous revolt of the "hookeuses" (during 1936-37) centred on the issue of wages (that is, price paid per square foot). Chéticamp gained international attention from the 1920s onward because of its hooked rug industry. The local craft went through a dramatic and thorough transformation at this time when M. Lillian Burke, an American designer/occupational therapist and friend of the illustrious Mabel and Alexander Graham Bell family, began to work with rug hookers. In this economically strapped community Burke found a workforce willing to accept her direction and design ideas and the combined efforts of workers and designer quickly put Chéticamp on the map. Numerous newspaper and magazine articles highlighted their larger projects. The most famous rug, modelled on an Aubusson carpet in the Louvre, measuring 18 feet by 36 feet (5.4 x 10.8 metres) and considered at the time to be the largest hooked rug ever made, received particular attention.34 However, the price of such success entailed long hours of home "factory" work to produce these handmade goods for a largely up-scale American marketplace. Division in the community arose when workers, inspired by discussions in study groups organized by the local co-operative leader, decided to petition Burke for higher wages. She had been paying, on average (although occasionally higher for more intricate work), from seventy-five to eighty cents per square foot and workers asked for one dollar. Her refusal led to a significant number of workers breaking off to work cooperatively. Eventually Burke had to pay those who remained faithful the higher rate.

31 While wages provided the flash point for the confrontation, in fact, Burke's workers were making more or less the same as independent rug hookers throughout the province and undoubtedly far more than they had previously made from their handwork. However, the nature of the work had changed. No longer an activity that women did when other commitments slackened (for example, in the winter season when outdoor chores were reduced), the pressure of fulfilling orders for a demanding urban clientele introduced the relentless clock of modernity35 and, as Ian McKay has pointed out, in "the scientific redesign of work, conception and execution were separated; conception of the carpets took place in New York, while the rugs were executed in Chéticamp." McKay addresses the exploitative nature of Burke's enterprise and the process of cultural appropriation whereby, in a curious inversion, the designer claimed that those who defected were "guilty of a kind of aesthetic misappropriation."36 The break-away workers were engaging in their own local craft tradition, but because Burke had transformed it so utterly, she felt that she "owned" the exclusive rights to its employment in the community. Burke fought but lost the battle to maintain control. While her outsider status (in terms of class and nationality, and to some extent, gender) undoubtedly worked to her advantage in orchestrating the reinvention of the rug-hooking tradition (that in itself was barely one hundred years old), two regional factors, one traditional and the other newly minted, ultimately proved her undoing.

32 First of all, among mat hookers in Nova Scotia, the concept of "ownership" of patterns was non-existent. Patterns were commonly shared, and if anything, imitation would have been considered the highest form of flattery. While creative individuals might attain a distinctive style and there were regional design trends, considerable borrowing and adapting of patterns occurred not only between rug hookers themselves but also between hookers and commercial pattern makers. Inspiration for patterns could come from anywhere —magazine and calendar illustrations, the decorative border around a cigarette package, motifs from the natural world — all might be employed in a hooked mat design. Ironically, even linoleum tilings furnished design ideas for some hookers. Burke herself borrowed from earlier French influences, particularly Aubusson and Savonnerie carpet designs. Not surprisingly, Chéticamp rug hookers failed to understand or comply with Burke's idea of ownership.

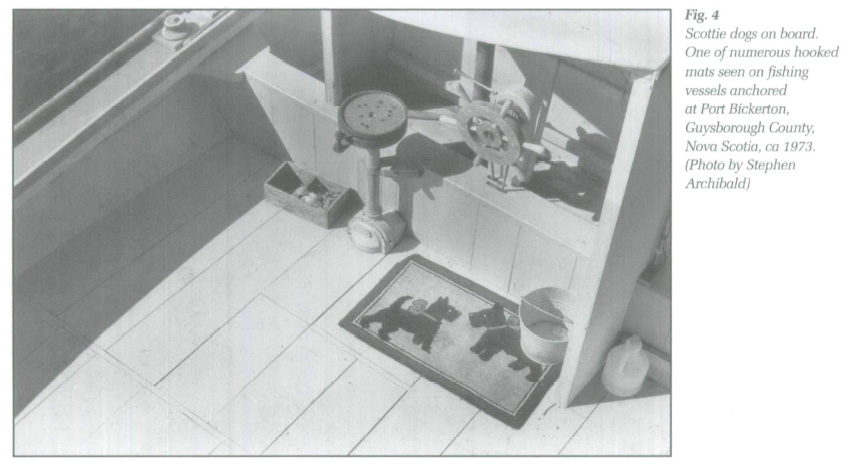

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 433 The second factor had to do with the emergence of the co-operative movement as a form of community empowerment. One can imagine Burke's chagrin when her amenable Chéticamp workers chose independence. After all, she had proved how successful they could be with her guidance. Too successful, perhaps: the market had been established. By this time, with or without Lillian Burke's help, Chéticamp products would sell like hot cakes.

34 Appraisal of Burke's legacy has been mixed and because her personal records have yet to surface, there are still some missing pieces of the puzzle. Burke was accused of making huge profits on the sale of Chéticamp hooked rugs; however, it is likely that such profits were exaggerated. Realization of larger profits occurred once the rugs changed hands on the American market. Nevertheless, T. J. Jackson Lear's analysis of the Arts and Crafts proponents who shifted from humanitarian reform to unwitting accommodation to "the corporate system of organized capitalism" might well apply to Burke, the occupational therapist, who began with a desire to help impoverished rural women maximize their potential earning power. As her investment in the Chéticamp project grew, her commitment to social betterment may have been overtaken by desire for personal fulfillment or gain.37 Under the harsh light of today's critical analysis it is, perhaps, too easy to pass judgement on a single woman of the early twentieth century who sought to make her creative mark in a world with limited opportunities. Through Burke, Chéticamp gained an enduring and unique industry that the community continues to claim proudly as its own. Without question, Burke's stylistic and technical approach has been naturalized. It is now the Chéticamp tradition.

35 Until 1939, the hooked mat market continued to thrive. With the eruption of the Second World War, rural women shifted their attention away from hooking. They turned their labour and talents to the production of relief supplies for the war effort or moved to higher paying industrial jobs. Lillian Burke reported as much to the Canadian Handicrafts Guild during the war. In 1944 she wrote, "When the girls come back after the war, I hope the industry will start up again. In the meantime the small orders attempt to keep it alive."38

36 In addition to the shortage of workers, burlap became scarce. The John E. Garrett Company closed its doors for a period of time during the war after torpedoes sank ships carrying their orders of burlap from Scotland.39 Because the war had blocked access to source countries in Southeast Asia, the Canadian government placed an embargo on the use of burlap other than for specific wartime necessities.40

37 In the postwar period, some women resumed rug hooking for the market and the Handcrafts Division of the provincial government, recognizing that hooked rugs still attracted buyers, helped to promote the industry through directories for tourists and exhibitions (both in and out of province) with on-site demonstrations of rug hooking. Even as late as 1951, according to a survey conducted by the Handcraft Division, Department of Trade and Industry, hooking constituted the largest income-producing craft, representing forty-three percent of the total annual reported craft income in the province. However, even at this time, the estimated retail value of new rugs in gift shops ranged in price from $2 per square foot for rugs made with cotton rag to $3.50 per square foot for Chéticamp fine wool yarn rugs.41

38 With the growing prosperity of the 1950s, most rug hookers ceased to hook for economic reasons (with some notable exceptions such as Chéticamp). By the late 1950s and early 1960s, a return to hooking as a hobby or creative outlet actually transformed the craft into one more akin to its origins, at least superficially. However, instead of employing designs from the traditional Nova Scotian repertoire that early American collectors so avidly sought out, the new rug hookers more often looked to the United States for instruction and design direction, thereby creating a new dynamic in the cross-border trade concerning hooked rugs.42

39 Today, there are many hooked rug enthusiasts throughout North America. While there is still a considerable trade in antique hooked mats as is evident in the world of e-commerce and sale reports in the Maine Antique Digest, as often as not, the cross-border business is in the form of hooking workshops, magazines, supplies, and modern hooked art works. Among recreational rug hookers, the social aspect of hooking has been revived, harking back to earlier mat parties. However, rug hookers usually meet to work on their own individual rugs rather than group projects. They are not helping their neighbour to finish that rug for the parlour. As well, today's rug hookers are more likely to hang their works on the wall rather than allow people to walk on them. This indicates a considerable cultural shift in the meaning of the hooked mat.

40 One might ask why hooked mats, among all the craft traditions, created such a stir in the marketplace in the post-First World War period. What was implied by the phrase "hooked mat mania"? To begin with, we must consider that while hooked mats enjoyed great popularity at the time, the term "mania" should be regarded with caution. Historians (this one included) are likely guilty of taking the journalistic hyperbole of the period too literally. Viewed within the broad spectrum of consumer goods available at the time, hooked mats probably represented a relatively small place in the market.

41 Hyperbole aside, hooked mats did capture the attention of a diverse public. To be sure, antimodern sentiment played a large part in creating a nostalgia for objects associated with a time before time was standardized.43 Affluent Americans, disturbed by modernity and the imagined loss of a more innocent world, found in rural Nova Scotia a place that they perceived as forgotten by time. Still a place where women made their own floor coverings, Nova Scotia and its craftworkers appeared untouched by the rush of urban life.

42 However, there are other factors to consider. If one looks to the material objects themselves and the period literature, it is apparent that antimodernism may have been a trigger, but it does not account in total for the hooked mat's appeal. To ask, as Thomas Lackey did, "what happens when a folk craft tradition meets popular and commercial culture," it is useful to look at the John E. Garrett Company (or Bluenose) patterns produced over the company's many years of operation. The business took full advantage of the rage for antiques, but their pattern catalogues included not only "old-fashioned" designs, but modern designs as well. Lackey notes that "images migrating up from the folk culture and downward from more elite styles met in the designs issued by the Garretts."44 When John Garrett's son, Frank, took over as the designer in the 1920s, he introduced a whole new range of design choices that were decidedly modern, influenced by art deco and commercial art. The Garretts were not alone in this trend. Other pattern companies and popular magazines offered similar fare. The Women's Institute pamphlet "Hooked Mats and How to Make Them," published in 1927, included only one illustration of a traditional pattern. All other illustrations and suggestions urged originality or copying from magazines or other contemporary sources.45

43 Kent, Waugh, Foley and a host of other arbiters of taste who wrote articles on hooked mats during the period usually decried the commercial pattern mats (and the garish use of bright colours), but a careful survey of their books and articles reveals that they could not always distinguish a pattern mat from an "original." As well, those with elite tastes who could afford antique mats at escalating prices accounted for only part of the market. Rug hookers in Nova Scotia during the period of high popularity produced not only traditional designs, but also tapped into a vast array of images from popular culture. One can only speculate on how many Scottie dogs and Bluenose sailboats graced the floors of bedrooms and dens over the decades since their first introduction in the 1930s. One of Garrett's all-time pattern favourites was a storybook-like image of the Three Bears, first published in 1932. Fifty-five years later, Canadian Living reissued the pattern for a whole new generation of hobbyists.46

44 Finally, the hooked mat's appeal had much to do with accessibility. For both the maker and the consumer, the craft allowed unlimited design possibilities, from the subtle to the blaring to the humorous, from "high" to "low" art. In spite of their elevated and precious status in some circles, hooked mats still remained primarily functional. With limited exceptions, no matter how decorative, they still were meant to be walked on.47 Handcrafted, they had more individuality than factory-made rugs but they did not have to be treated as objets d'art. Solidly part of popular culture, hooked mats were made by and for the people.

45 For Nova Scotian women in the late nineteenth century, mat making was a creative, practical, and social activity. During the first quarter of the twentieth century, collectors and dealers transformed hooked mats into consumer products severed from their primary function, social context, and provenance.

46 Initially rural women must have been mystified by the rug hunters' curious quest. If it seems that they handed over their rugs rather easily, a number of reasons are suggested. One hundred years ago, people opened their doors and offered hospitality to travelling strangers more readily than is the case today. In Kent's account of his rug hunt in Canada, he recalls stopping at one house where the woman assured him that she had no rugs to sell, but offered him and his companion a place to rest. Before they left, the woman offered to give him a rug to take to his wife. Kent wrote:

47 One suspects that many women found it difficult to attach monetary value to their home handwork and that in the face of audacious offers from rug hunters, the only polite thing as a host was to accede to the wishes of the guest. With their skills and the availability of recyclable materials, rug makers could always replace an old rug. They were used to discarding or downgrading rugs to domestic locations of lesser importance as they became worn. What they may not have anticipated was a loss of rug-making interest or need among the next generation. Times were changing. Even where rug hooking continued, increasingly it was driven by economic more than sociocultural forces and the design approach was shifting. The dearth of older examples in the province meant a significant loss of the traditional pattern repertoire.

48 Ironically, although collectors essentially stripped the province of its earlier hooked mat heritage, without their interest and the subsequent hooked rug craze, it is probable that even less would be known about this craft tradition. Had rural Nova Scotians been more affluent earlier, they might have replaced old and worn mats with modern commercial floorings sooner, happily discarding the remnants of another age. The people who could afford to modernize the earliest (often the movers and shakers in industrial capitalism) were the very ones charmed by and greedy for traditional objects that represented a lost past. Whether collectors sought hooked rugs as "trophies of the hunt" or as homey reminders of a bygone era, they did so "as the locusts in Egypt gathered crops." In the process, the objects were separated from their historical roots and acquired new meaning.

49 That American buyers relied so heavily on Nova Scotia and the other Atlantic provinces for their supply of an artifact that most considered quintessentially New England in origin might be regarded as another irony. Writers of the period acknowledged the presence of Nova Scotian rugs in the antique market, yet it is unlikely that anyone had a clear concept of the volume of cross-border trade. The surprisingly large export figures reported in the newspapers of the late 1920s and early 1930s (not including all earlier trade) take on even more significance when one reflects on the comment made in 1918 by writer Nina Wilcox Putnam that "perhaps three or four thousand [hooked rugs] are in existence in the entire country [United States]."49 Putnam may or may not have had an accurate assessment of the existing number of rugs in the country; nevertheless, her estimate provides a starting point for considering the prominence of Nova Scotian mats in circulation among antique collectors of the period.

50 Over time, women in Nova Scotia learned to take advantage of the market and turned to the commercial production of hooked mats. Especially during the Depression, whole communities came to depend on the income accrued from such labour. In spite of the incalculable loss of Nova Scotian material culture through exportation, the commodifying of hooked mats did provide critical economic benefits to rural families when there were few other options for employment or income.

51 William Winthrop Kent's Nova Scotian hooked runner returned to the province for a price that far exceeded what he originally would have paid for it. That Kent, one of the most prominent of the early collectors and writers on the subject of hooked rugs owned this runner adds considerably to its historical interest. But for serendipity, this icon of traditional Nova Scotian craft would not have made its homeward journey, for fate very nearly relegated the runner to the dustbin. Through its story of survival, the hooked mat has gained a further layer of mythic meaning.

52 Crossing the border for a last time, the runner's function changes once again. As a fine example of Nova Scotian material culture, it will serve as an interpretive tool in the museum's developing history of mat making in the province.