Articles

Go Down Moses:

The Griffin House and the Continuing Struggle to Preserve, Interpret and Exhibit Black History

Abstract

The following study explores the ongoing development of The Griffin House in Ancaster, Ontario, a historic home dedicated to commemorating and communicating the history of the local Black community. Drawing upon the current museological framework, this paper analyses the institution's origins, exhibit, outreach programs, educational initiatives, and future goals. It seeks to understand the impact that these theories and practices have had upon the actual form, content, and operation of a museum dedicated to the preservation, interpretation and display of African-Canadian history. As well as demonstrating the tremendous promise and successes of Black history endeavours, The Griffin House reveals the conflicts and concerns that continue to plague efforts at integrating the lives and stories, the cultural heritage and contributions, of African-Canadians into the historical and museological narrative.

Résumé

Cette étude porte sur l'évolution continue de la Maison Griffin à Ancaster, en Ontario, une résidence historique dédiée à la commémoration et à la communication de l'histoire de la collectivité noire locale. Puisant dans le cadre muséologique actuel, l'auteure analyse les origines de l'institution, ainsi que l'exposition, les programmes de sensibilisation du public, les initiatives éducatives et les objectifs futurs. Elle cherche à comprendre l'incidence que ces théories et pratiques ont eue sur la forme, l'exploitation et le contenu actuels d'un musée consacré à la préservation, à l'interprétation et à l'exposition de l'histoire afro-canadienne. En plus de mettre en évidence la formidable promesse et les succès retentissants de l'histoire des Noirs, l'auteure de cet essai souligne les conflits et les préoccupations qui continuent de saper les efforts déployés pour intégrer les vies et les histoires — l'apport et le patrimoine culturels — des Afro-Canadiens dans l'exposé des faits historiques et muséologiques.

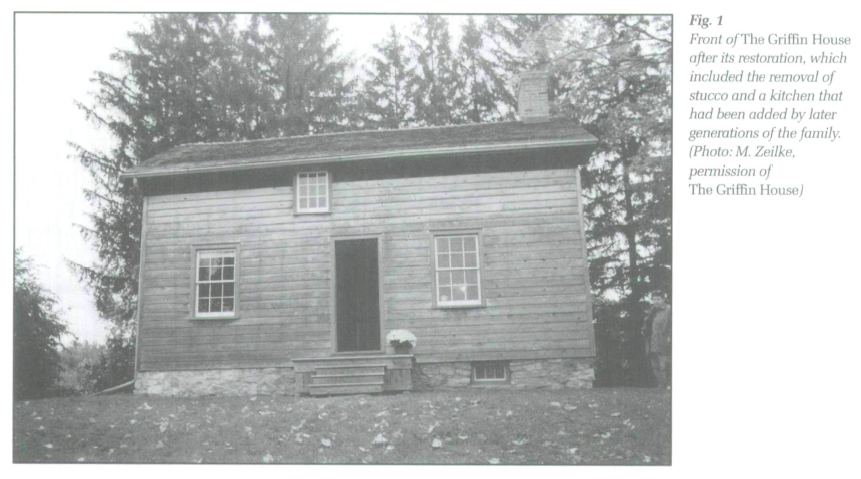

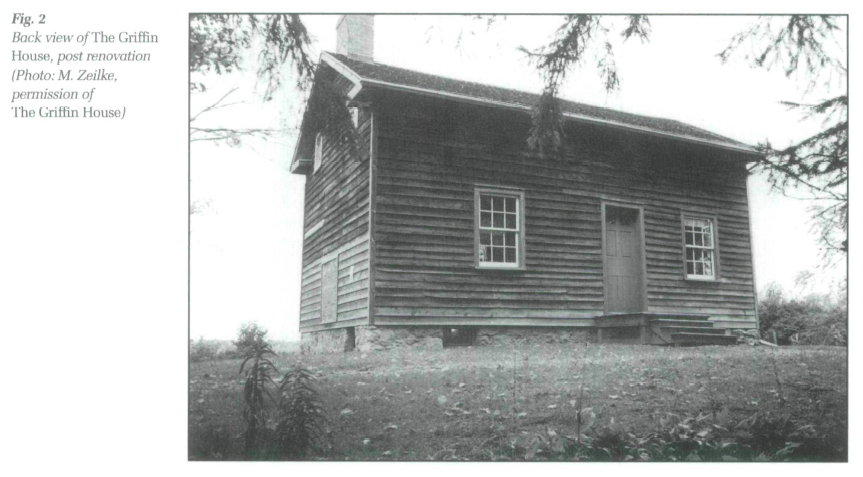

1 The Griffin House in Ancaster, Ontario, provides a uniquely Canadian perspective from which to explore continuing efforts to preserve, study, interpret, and exhibit the lives, cultural traditions, and history of the Black community. In its commemorative and interpretive role as a centre for African-Canadian history, The Griffin House embodies many of the thoughts and ideals expressed within the theoretical and methodological framework of the new museology. The site, a restored Regency home set on eighteen hectares of property, combines an intimate look at a remarkable local farming family, the Griffins, who lived at the homestead from 1834 to 1988, with a multi-faceted and meaningful exploration of the lives and struggles, the culture and contributions, of the area's early Black settlers. The museum's mission and method is predicated on the belief that "[t]here's more to our history than the United Empire Loyalists."1

2 Indeed, The Griffin House has elicited praise from the Black community for its sensitive, thoughtful, and insightful commentary on and handling of African-Canadian issues as an integral part of Canadian history. Its value as an educational resource has attracted schools from as far away as Buffalo and, as part of its outreach program, plans are currently underway to participate in a resource network of Black history sites in the area. The museum's careful attention to text and visuals, the value it places upon the input of the African-Canadian community and the Griffin family itself, indicates that exhibiting other people's history is a complex task. In showing the history of the Black community as part of the larger society's developmental narrative, this site demonstrates a desire to move beyond the traditional milieu of the two agencies that oversee its operation: the regional conservation authority and the local museum. Yet, The Griffin House project was and continues to be plagued by funding difficulties and controversy, including allegations of racism. While this site indicates the enormous promise and possibilities of integrating Black stories into the existing historical and museological narrative, it also suggests the continuing presence of tensions and obstacles in achieving a fully-realized and illuminating chronicle of the heritage of the African-Canadian community.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 In order to grasp the interpretive role and implications of The Griffin House, it is necessary to understand the manner in which the theoretical and methodological framework of the new museology has influenced the commemoration and communication of the heritage of the Black community. The innovations and illuminating ideas contained within and made possible by this philosophical orientation posed a fundamental challenge to the composition, content and interpretation of the conventional historical narrative. Traditionally, it was determined by, and affirmed the values and sensibilities of, the dominant culture. It was their stories, assumptions, expectations, and beliefs that were reflected within and reinforced by the definition and presentation of historical "truth" in museums.

4 Beginning in the 1970s and 80s, first with the emergence of the multi-disciplinary revisionism of the new social history and, later, with the prominent musings of philosophers like Foucault and Derrida, the validity of the traditional historiographical stance was questioned and undermined.2 Historians increasingly sought to retrieve and analyse the stories of the ordinary people, including Blacks, women, and immigrants, who were categorized as the "other." With the growing recognition of the ability of language to reflect and shape ideology and power relations, came the realization that the "self" versus "other" dichotomy formed the fundamental underpinning of the European worldview.3 Those people who spoke with different voices were deemed inferior and were either misrepresented or silenced completely in a historical text that was designed to achieve and perpetuate the authority of the developmental narrative that was desired by the cultural "norm," the European.

5 Contemporary museologists are more self-reflexive and aware of their role in serving a cultural agenda. There has been the gradual realization that the museum itself is a cultural text. As it is a product of its historical context, the role and responsibilities of a museum, as well as its form and content, change over time. Indeed, these institutions must change in order to remain relevant.4 In addition, museologists have begun to engage in a more thoughtful and detailed exploration of the multiplicity of perspectives and stories that belong to the individual members of the diverse communities that comprise a pluralist society. They increasingly attempt to relate to and inspire their diverse potential audiences, respecting differences and encouraging them to draw on their own unique backgrounds and experiences in deciphering an exhibit.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 26 Attempts to integrate the stories of diverse communities and cultural outsiders into mainstream museums have led to increasing efforts at involving the community directly in the staging of an exhibit. Endeavours on the part of museum professionals to incorporate the voice of the people into the representation of their materials and history reflects the larger struggle to restore authority and agency to those cultural groups who were previously objectified, classified and decontextualized in order to achieve the interpretive goals of the museum community.5 When curators thoughtfully and respectfully reach out to the community while mounting an exhibit, the result is a richer experience that integrates the subjective, powerful voice of the people whose story is defined and conveyed in the museum's text.6

7 Stemming from larger quests for cultural pride, self-empowerment, and self-determination, there have been increasing calls on behalf of cultural groups to directly reclaim their histories and their identities through community based museums where they can preserve, research, interpret, and share their stories. These sites acknowledge the importance of relating history to today, of presenting a more fluid and fully realized expression of cultural identity. Similarly, these institutions serve a strong educational role. They seek to instruct young people in the traditional knowledge, customs and values of the culture and thereby instill a sense of self-esteem and meaningful identity.

8 An early example of a successful African-American community based museum is the Smithsonian Institution's Anacostia Museum of Washington, D.C., which was established in the 1960s. Both in mainstream and community based sites there have been attempts to forge long-term relationships with diverse cultural groups by involving them in the life and work of the institution, including exhibition planning and policy making decisions; the hiring of culturally diverse staff; and ongoing consultation with the community through the establishment of advisory boards. These efforts help make museums significant to, and thereby encourage the participation of, people who were traditionally alienated from these institutions. In the process, the appeal of museums is extended beyond its non-traditional audience.7

9 In order to understand the significance of The Griffin House in terms of African-Canadian heritage, as well as the unfolding of Ancaster's history, it is valuable to briefly examine the story of the Griffin family, which stands at the forefront of the museum. In essence, there are two questions to be asked: who are they and why should we care? In approximately 1793, an African-American man named Enerals Griffin was born into slavery in Virginia. Eventually, Griffin escaped and made his way north using the Underground Railroad. By 1829, he had married a woman of European background named Priscilla and they settled in the Niagara area. In 1834, the young family, now including their son James who was born in 1833, settled in Ancaster. The Griffins purchased a simple, working-class Regency style home that had been built in 1827 upon fifty acres of farmland in the beautiful Dundas Valley.

10 The family's descendants lived on the homestead until 1988. Although the family was fairly prosperous, the middling quality of the land necessitated that they help support themselves by pursuing work in the community; assorted Griffins laboured as hotel keepers, butchers, stagecoach drivers, and veterinarians. The Griffins were one of the earliest, if not the first, Black families in the area. In 1851, there were only 27 Blacks out of a population of 4 400 people in Ancaster, and over time the family intermarried with their white neighbours until their identity by colour virtually disappeared.8

11 An exploration of the people and events surrounding the acquisition of the property by the Hamilton Region Conservation Authority (HRCA) and the development of the Griffin project, serves as an intriguing and illustrative entry point for achieving an understanding of the dynamic and conflicting forces at play in the origination of the site. In 1988, the HRCA bought the property from a Griffin descendant named Bernard Griffin-Costello as part of its land management mandate; they planned to tear down the home and its surrounding outbuildings. After doing the requisite research, the HRCA learned of the novel tale that unfolded within the home's walls. Suggestions of turning the home back into a private residence were overruled and the conservation authority resolved to convert the site into a centre for the interpretation and study of local Black history. In 1991, the home, a rare surviving example of vernacular early nineteenth century design, was designated a notable site by the Ancaster Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee (LACAC) because of its "unique historical and architectural significance."9 However, the events that followed would reveal both the continuing reticence of the dominant culture to respect and incorporate the alternative stories of diverse cultural groups as well as indicate the self-affirming attitudes and efforts of traditionally ignored or misrepresented people in claiming a place to memorialize and share their cultural heritage.

12 Although the project was approved in principle by 1992, with archaeological work underway at the site, the hopes of eventually restoring the home to its pre-1850 glory and opening it to the public were increasingly tenuous in the face of controversy and opposition by some members of the Ancaster community. The jeopardy in which the proposal found itself was so great that according to the HRCA's director of planning and engineering, "in the air there was a feeling that Griffin House was not going to happen at all."10 According to some members of the Ancaster community, who achieved their most vocal manifestation in the form of the Valley Homeowners Association, their dismay at and concerns surrounding the proposal to make the Griffin house into a historic site centred upon several contentious issues. These included the estimated high cost of the restoration; the crowds and traffic it would create, presumably from "special interest" bus tours; the noise that would accompany a busy tourist site; and worries about the eyesore of a parking lot on rural land. Initial estimates for the completed heritage centre ran upwards of $280 000 and included plans for a full restoration of the home as well as an addition that would allow for an exhibit hall, library and meeting room. Several Ancaster township representatives called for the removal of the home to Westfield Heritage Village, a living history site owned by the HRCA in nearby Rockton as a means of achieving the twin goals of saving money and keeping tourists away.11 Despite the protests, many members of the HRCA continued to argue in favour of preserving the Griffin homestead.

13 The wrangling over the future of the project required months of negotiation between the residents, the Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee, and representatives of Hamilton's Black community before a final decision in favour of proceeding with the restoration was reached in November 1993. The renovation and mission plan that was approved by all participants, from the Town of Ancaster to the area's Black community, was a scaled down version of the one that was initially hoped for and proposed. Approximately $90 000 was to be spent on restoring the home and landscaping the yard with an additional $30 000 to be used to build a parking lot across the road from the Griffin house at the Hermitage site as well as developing a walking trail from it to the homestead. Although the province had initially granted the HRCA $70 000 for their preservation efforts, the more limited scope of the final project resulted in a one-third reduction in the amount of money that was promised by the Ontario Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Recreation to approximately $40 000.12

14 The acrimonious dispute surrounding the future of the Griffin house engendered multiple meanings for the diverse individuals touched by the unfolding story. Although the Valley Residents Association vehemently denied the charges, several prominent Hamilton councillors blamed the racism of affluent (and white) Ancaster homeowners, who had the financial clout and social influence to place considerable pressure on the HRCA, for the cutbacks to the previously more substantial undertaking. Indeed, one Hamilton councillor was quoted as saying "The racists won...I truly believe that if Mr Griffin had been white, the project would be going ahead with all the support and interest it deserves."13 The councillor also claimed that while attending a committee meeting where the subject of the Griffin home was under discussion, he heard several Ancaster residents state that "they didn't want coloured people in the valley."14

15 Not surprisingly, the Black community of Hamilton-Wentworth expressed strong concerns about the future of the intended heritage facility and questioned the integrity of the project and the people overseeing its development. The chairperson of the heritage committee of Stewart Memorial Church, the historic and present day spiritual and social centre of Hamilton's Black community, was certain that racism fueled efforts to quash an undertaking of tremendous importance to local African-Canadians. She commented that the compromise "makes me feel bad because I like to think that we are all one and everyone thought the same, but obviously that is not the case."15

16 Fieldcote Memorial Park and Museum in Ancaster, which oversees interpretation, programming and publicity for The Griffin House, was caught in the whirlwind surrounding the site from the outset. Former curator/manager Jennifer Dunkerson contends that while a "not in my backyard" mentality existed, there was also a "lot of prejudice" and a "lot of the things [the opponents] said sounded like excuses for their prejudice."16 The whole situation was quite "sad."17 Certainly, the site is not overrun with visitors by any means and their fears appear largely unfounded. Ironically, even the Ancaster Historical Society, which presumably would have had much invested in the success of the proposal, has not been a particularly strong advocate of or directly involved with the site, although it supports it in theory.18 The attitudes and actions surrounding the origins of the museum demonstrate the persistent devaluation of and attempt to compromise the voices and history of those people who lie outside of the dominant culture. Not only did many members of the Ancaster community fail to appreciate the history of the Griffin family as illustrative of and integral to gaming a richer understanding of the local narrative, they failed to perceive the responsibility that the HRCA bore to protect that heritage as well as encouraging its further study and dissemination.

17 Despite the controversy surrounding this centre, the Hamilton Region Conservation Authority sought to facilitate the involvement of the local Black community in shaping the form and content of the museum's representation of African-Canadian history. Indeed, the conservation effort was hailed by Black activists who were both anxious and enthusiastic to be involved in the work of restoration and interpretation. According to one local activist, the project was "worthwhile and marvelous" as "it's the only piece of [B]lack history locally that links us to the slave era."19 The home was prominently featured in complimentary articles appearing in newspapers dedicated to Black cultural issues as well as being well received by the Ontario Black History Society. The Black press stressed its merit as a site that presents a vision of the struggles, perseverance and eventual triumph of a close-knit Black family headed by a powerful father figure.20

18 As soon as the HRCA discovered the African-Canadian background of the Griffin family, they attempted to forge a close working relationship with Stewart Memorial Church. An informal advisory committee was established in order to enhance the exhaustive research and restoration being conducted by the staff and volunteers of HRCA and Fieldcote Memorial Park and Museum; their understanding of "what life was like" for African-Canadians benefited from the advice and insight provided by the Black community. In addition to sharing their personal knowledge and oral histories, the advisory group would suggest that the researchers consult with specific sources of information and explore certain people and events; the museum staff would then follow up on the lead offered them. Often, their investigations would result in the examination of traditional sources including newspapers, archives, census data, assessment records, and church records as well as several interviews with older family members or friends of the Griffins in order to reconstruct as comprehensive and detailed a narrative as possible.21

19 An invaluable resource for the researchers was the work of local educator and advisory group member Neville Nunes. The Hamilton Public Board of Education teacher had developed a curriculum on the Black heritage of Hamilton-Wentworth, including the Underground Railroad, with both classroom and field-trip components. He shared his methods and findings with the HRCA and Fieldcote.22 Members of the committee from Stewart Memorial Church were, along with the Griffin descendants, the first group to tour the site and have never expressed anything but tremendous pleasure and pride in the completed product.23 The empowered involvement of local African-Canadian people, the recognition of the valuable contribution they offered in terms of sharing and shaping the representation and meanings attributed to their past and present identity, demonstrates the mutually beneficial experience rendered possible by and good feelings engendered through collaborative efforts between the museum and the community.

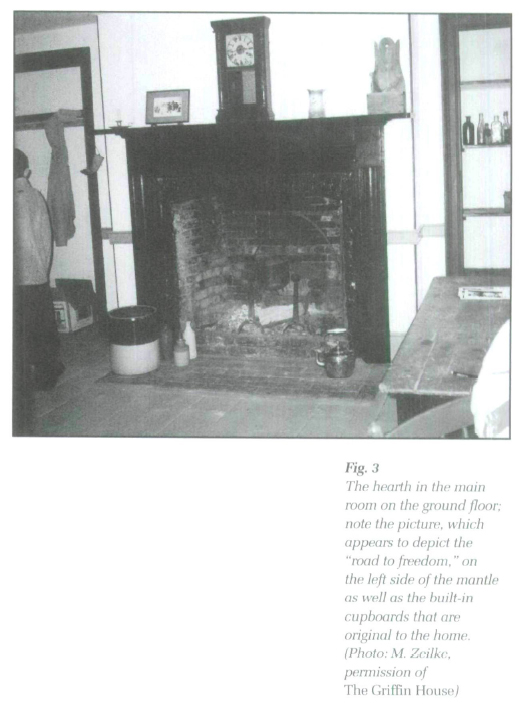

20 Since its official opening in February 1995, The Griffin House's impressive, informative and intriguing exhibit has sought to integrate the unfolding narrative of a single Black farming family, the Griffins, from 1830 to 1988, with the heritage and contributions, the diverse interests, roles and experiences, of the early Black community in Hamilton-Wentworth.24 In turn, text panels grapple with Griffin specific issues such as their family tree and the history of the farm before exploring pertinent topics in local Black history, including: slavery; an overview of Black settlement in Hamilton-Wentworth; domestic lifestyle; employment, religion; education; and a discussion of important Black citizens. By drawing connections between the individual and the larger cultural group the family experience is contextualized, it is understood as part and product of a certain sociocultural dynamic. Yet, the interpretation of this history reflects the conflicted history of the site. The Griffin House inhabits a tenuous position somewhere between a community museum, in the sense that its express purpose is to illustrate Black history, and a mainstream museum in that it is run by two traditionally white, and conservative, organizations — one a governmental body and the other the local heritage centre. At the same time, the Black community's participation in shaping the form and content of the museum's text has been of the utmost importance in determining the way in which the site addresses Black issues and heritage.

21 An examination of the exhibit design, including the utility and display of artifacts, as well as the study of the text panels reveals that The Griffin House seeks to challenge and expand the visitor's current framework for reaching a meaningful interpretation of Black history; the historic home encourages the viewer to "look deeper" and appreciate the manifold definitions and interpretations of Black history that are possible while understanding the vitality of this narrative to the Canadian past. At the same time, however, the museum has a somewhat conflicted desire to portray the African-Canadian community as both part of and distinct from the operation of the larger, more dominant, Anglo-Canadian culture.

22 In order to construct and convey an image of the strength, independence and integrity of the Black community, the text panels assume the African-Canadian perspective. Therefore, the panels' titles read "Where We Worked," "Where We Prayed," or "How We Celebrated." This suggests that the people themselves are describing their lifestyles and traditions. By sharing their story they are defining their past and present identity, they are deeming what is of value and we, the visitors, have the privilege of listening to an insider's account. By including actual quotes from members of the Black community, by using their own words to articulate their hardships, endeavours, and accomplishments, The Griffin House text restores voice and authority to a people who have alternately been silenced or misrepresented. One quote featured in the discussion of slavery comes from a man named Henry Williamson circa 1856: "I would rather be wholly poor and be free, than have all I could wish and be a slave."

23 Similarly, photographs of people in the community, including a Brownie troop, flesh out the text. The image of an Ancaster domestic servant named Edna Buckingham that was taken in 1915 is a study in contradiction: the young woman's proud, smiling demeanor contrasts sharply with her tattered clothes. Another section simply lists the names of various Black men and women as well as their professions, ranging from tailors to porters. Finally, at another point in the display, considerable attention is paid to a detailed inventory of Enerals Griffin's farm, his livestock and crops, as though to highlight his success. The presence of pictures, names, and quotes from individuals in the African-Canadian community serves to make the museum experience more evocative, powerful and poignant; it makes it "real." Words and images humanize and personalize an exhibit that could have rested on the facts and figures of Black settlement thereby making it much harder to see the individual presented as "the other." At the same time, the exhibit portrays the diversity and richness of the African-Canadian experience by presenting them as a vibrant and active people.

24 The desire to communicate ideas of agency, advocacy and self-esteem, and thereby avoid the traditional denial of these forces when representing historically oppressed peoples, pervades the text. Great pains are taken to destroy the image of African-Canadians as victims. In part, this is accomplished by recounting the mythology surrounding Enerals Griffin's escape from slavery. Oral history contends that his owner, Edward Lee, had promised Griffin his freedom upon his master's death. However, when Lee was on his deathbed and nothing had been arranged, Griffin decided to take "matters into his own hands" and secure his own freedom.25 As he knew how to read and write, Griffin wrote up a note granting himself a pass and forged his master's signature. The note allegedly read: "This nigger belongs to me. He has my permission to go to town and visit the sick negroes in my place. Signed, Edward Lee" The exhibit's reproduction of this letter is one of the most pivotal keys to understanding the site's historical interpretation. Similarly, although the letter is not authentic, it is the aspect of Griffin's story that appears to instill the most admiration and enjoyment in the Black community and press.

25 Another letter reproduced within the text further alludes to self-affirming protests against ill-treatment. In 1843, angered by the discriminatory that barred Black children from attending Hamilton's public schools, the residents of "Little Africa" on Hamilton mountain brought their grievances to the attention of Governor General Lord Elgin. They claimed the "right to inform your excellency of the treatment that we have to undergo. (We want)... for the children of colour to go to the public schools together with the white... all [we] want is justice."

26 Yet, perhaps due to lingering worries and fears related to the problems that surrounded the founding of the institution, the text deals with issues of discrimination in a somewhat hesitant manner. For example, although the text mentions that Black students were not allowed to go to Hamilton's public schools, the oppressor remains unnamed. It is never explicitly stated that the white community would not let Black kids attend the same schools as their children. As a result, it is a rather mild, somewhat gentle reproach for past wrongs. However, the Ancaster community does not escape completely unscathed. The town's participation in and perpetuation of the "peculiar institution" of slavery is highlighted when a text panel mentions that, in 1807, a young female household slave named Sarah Pooley was purchased for $100 by a local man named Samuel Haut. She is believed to be the first Black Ancaster resident. A rather subtle, yet still unpleasant, reminder that slavery was not simply an American phenomenon.

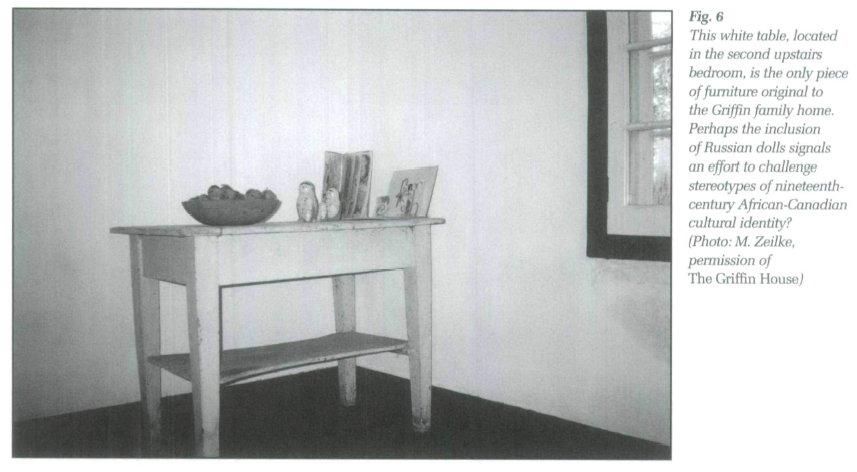

27 One thing that the museum really seeks to demonstrate is that while the Griffin family was African-Canadian, and a part of the cultural traditions of that community, they also belonged to the dominant Anglo-Canadian culture of the Victorian period. Perhaps in response to the difficulties encountered during its establishment, the museum presents an interpretive vision of and stance towards African-Canadian heritage that conveys an image of the Black community as very assimilated in their adherence to the norms and values of the mainstream culture. In part, this serves to challenge and undermine the pre-existing assumptions or stereotypes that visitors may possess in relation to what comprises "Black" culture or history. This stance encourages the viewer to consider the deeper meanings and diverse implications that are possible within and with regard to a single artifact.

28 For example, the main room features a large portrait of Queen Victoria hanging on the wall. At first, a picture of the British monarch who, as the "Mother of the Empire," served as a rallying point for the extremely powerful and oppressive ideology of colonialism appears to be an odd choice in a museum designed to communicate Black history. Yet, upon deeper reflection comes the realization that for a man who had fled a life of bondage in the United States, Queen Victoria was a symbol of the quest for freedom and the possibility of a new, better life and a more fully-realized personal identity in Canada. Historical research indicates that many nineteenth century Black families who lived in the area had two pictures featured prominently on their walls: one of Abraham Lincoln and the other of Queen Victoria.26

29 The exhibit also features a small sample of the almost 4 000 artifacts that were recovered during archaeological excavations on the site. As discussed by project researchers, "there was little evidence to reflect their [B]lack heritage and distinguish their life from that of other settlers."27 Objects on display include: sleigh bells, marbles, medicine bottles, a brooch, and a pipe with a shamrock motif. While these artifacts have clear links to the Griffin family, there is no way of verifying that they owned a picture of the monarch; the assumption that they were tremendously loyal to the Crown serves to forward a very specific interpretive vision. The message to visitors is that the Griffins were "ordinary" Canadians.

30 The minimal presence of many artifacts with specifically "Black" themes or subject matter, such as a picture of Abraham Lincoln or the button engraved with the image of a dove that was found on the site, as well as the emphasis on the present generation of the Griffin family indicates the often complex nature of the museum's interpretation. While the hearth's mantlepiece features a small picture that appears to depict a scene along the Underground Railroad, the most miraculous discovery to be uncovered at the home is the one that is missing. And, indeed, it is the artifact that would be the most poignant in terms of relating Black history. The object in question is an 1860s lithograph of an 1859 Eastman Johnson oil painting called Negro Life in the South, popularly known as the Old Kentucky Home print.28 According to the researchers, the print serves as a crucial link to the Black heritage of the Griffins and is a sign of people celebrating their culture.29 After being found in a downstairs closet, it was removed from the home for restorative work. Although a photograph of the print remains on site, the original was deemed too fragile to withstand the conditions of the house. It is now in storage at the HRCA.30

31 The interpretive slant that emphasizes the Anglo-Canadian cultural ties of the Griffin family as well as their Black identity is paradoxically refined and confused when considered in conjunction with the considerable role played by the present-day descendants of Enerals and Priscilla Griffin in the exhibit. While the museum neglects contemporary Black issues, a huge priority in most modern African-American community museums, the modern Griffin family is very much at the centre of the exhibit. A large picture that was taken at an informal family reunion during the restoration of the home is featured amongst the text panels.

32 Similarly, the display includes several newspaper articles featuring pictures of and interviews with assorted Griffins, most of which attempt to gauge their thoughts and feelings on their newfound "Black" heritage. One family member expressed her pride in her Black ancestor: "[f]or someone who started off as a slave to do so well, I'm impressed."31 Many Griffin family members, even those who lived in the Hamilton area, were unaware of their Black heritage and had never met any of their relatives. Newspaper articles stress that the "Griffin descendants...show no trace of their [B]lack heritage" and comment that "none of them knew they were related to this intriguing man."32 They only realized their connection to an escaped slave named Enerals Griffin after reading about plans to restore the historic home in the newspaper or after being contacted by Hamilton Region Conservation Authority officials who wanted to involve the family in the project. Upon being contacted by an HRCA representative regarding his link to the Griffin family, one man remarked that he was "awed" and thought that "she must have the wrong family."33

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 333 The prominence of interracial relationships that produced biracial children, along with the Griffin family's continuing intermarriage with the surrounding white community, blurs the fundamental dichotomy of self versus other; it transgresses and calls into question all racial categories. Perhaps this type of uncertainty and fluidity of racial definition was partially responsible for the extremely disturbed, almost hysterical reaction of the white homeowners that opposed the site. It could be suggested that the centrality of the current generation of visibly white descendants serves a twofold purpose. First, it breaks down racial categories in a gentle way by implying, very subtly, that race is socially constructed and that all people are equal. The text that relates and celebrates the history of die Black community extends from this sensibility. At the same time, the presence of visibly white family members "normalizes" the Griffin home. Rather than being deemed a minor topic relegated to the margins as "special interest" history, the museum integrates the saga of the Griffin family into "white" history — the dominant cultural narrative.34 The question begs to be asked, could this be motivated by a desire to placate the site's opponents? The tense situation surrounding the Griffin project speaks volumes about the struggle to carve a place for Black Canadians, and their history, in contemporary society.

Display large image of Figure 4

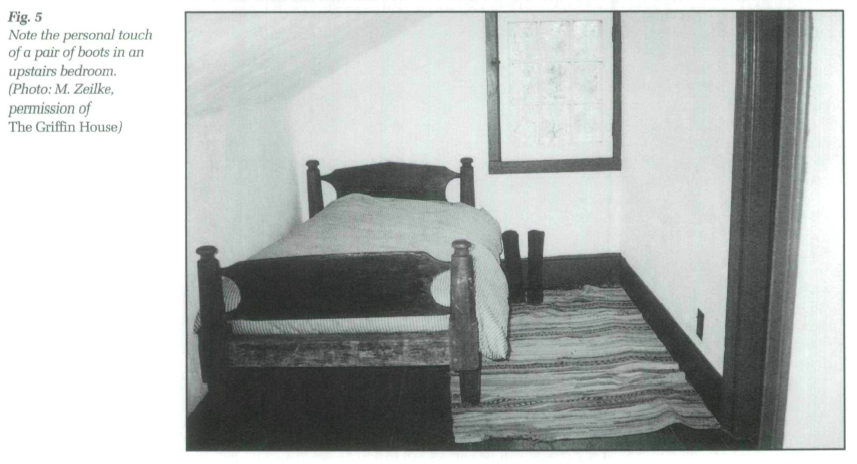

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

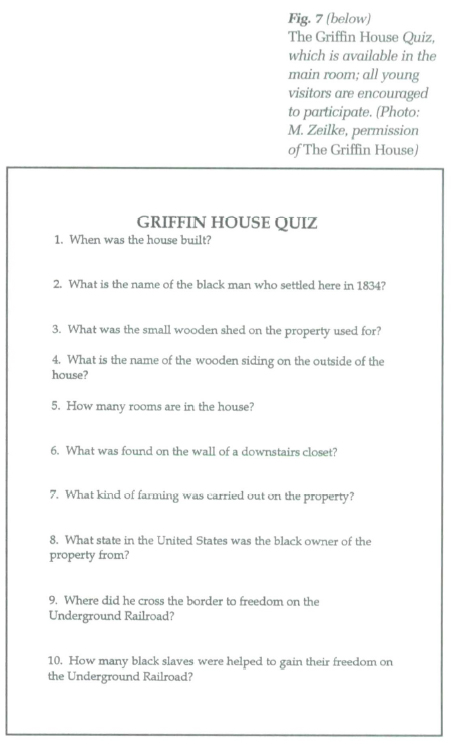

Display large image of Figure 734 Educational initiatives and outreach programs play a fundamental role in and serve as one of the central organizing principles of the operation of The Griffin House. As part of its mandate, the home seeks to increase awareness of and facilitate discussion about the Black community's multi-faceted role in and contributions to the development of the region. The HRCA and Fieldcote hope to attract a wide visitor base including Dundas Valley Trail Users, educational groups, history buffs, and special interest groups (i.e., Black heritage tours).35

35 While Fieldcote has prepared a worksheet entitled the Griffin House Quiz for young people who visit the site either as part of a school trip or on a family visit, a more structured and consistently utilized educational program was developed by Neville Nunes for the Hamilton Board of Education.36 This curriculum package is aimed at those high school and elementary school groups that engage in the International Underground Railroad Tour, a tour of significant sites along the road to freedom run through the Buffalo and Hamilton public school boards. The tour's emphasis on Black history and background, with the goal of providing a sense of social identity, serves a powerful didactic purpose. During a visit to The Griffin House a local African-Canadian student commented: "[i]n grade school, no one took the time to teach me about my heritage...For a long time I thought I didn't have any history."37 As with many Black community museums, The Griffin House takes its role in raising the cultural consciousness and pride of African-Canadian youth very seriously. The museum's emphasis on photographs of and tales associated with the Griffin family of both yesterday and today reinforces this notion of roots, of reaching back into the past to discover one's identity before moving towards self-realization and serf-actualization.

36 An exploration of the future goals of The Griffin House reveals the hope that participation in a newly established Central Ontario Network for Black History will encourage awareness of and interest in the historic home by linking it with other African-Canadian heritage sites in the Niagara-Hamilton region. This initiative illustrates the ongoing struggle to increase the amount of funding for Black history resources as well as suggesting the vital role played by community-driven support systems. The need for innovative, resourceful and co-ordinated self-help organizations is directly linked to the continuing devaluation, disaffection and general neglect of many of these agencies by existing authorities in the cultural sector. It is believed that by encouraging visibility and favourable word-of-mouth, the heritage tour will help alleviate some of The Griffin House's current funding difficulties. In turn, this will allow the museum to implement a more vibrant and well-rounded interpretation of the life of a Black farming family. This more rigorously detailed interpretive plan involves the completion of the home's restoration that began in 1993, increasing the number of visitors; extending the hours of operation and hiring additional staff, and the acquisition of a more extensive collection of artifacts appropriate to the era with which to decorate the home. Nothing short of the full realization of this "labour of love" is sought.

37 Therefore, by considering The Griffin House within the context of a museological framework, as well as within the confines of larger trends in Black history museums, it is possible to illustrate and understand the impact that these ideological constructs, and their attendant themes, have had upon the actual structure and operation, the form and content, of museums dedicated to African-Canadian history. At the same time, an analysis of the institution's origins, exhibit, educational initiatives, and future plans allows for a wider awareness of and cogent insights into the possibilities and triumphs, as well as the continuing conflicts and concerns, that face current efforts at preserving, interpreting, and displaying the stories and cultural heritage of the Black community.

I would like to thank Jennifer Dunkerson, Neville Nunes, and David-Thiery Ruddel for their comments on various drafts of this paper.