Articles

Moose Jaw's "Great Escape":

Constructing Tunnels, Deconstructing Heritage, Marketing Places

Abstract

The challenges of a post-industrial world are prompting new initiatives in marketing heritage as constructed mythologies, popular entertainment, tourism, and economic development. A combination of nostalgia for an imagined past, economic and cultural insecurity, and a growing demand for the consumption of entertainment has made a multifaceted engagement with the past the stuff of economic policy. What's going on? Is it a rear-window nostalgic gaze as our lives and places lose their distinctiveness in globalized morphings into a predictable sameness? Is it "place marketing in placeless times" as a late-industrial economic strategy? Clearly, heritage formation is a dynamic process and the very successful marketing of the Moose Jaw tunnels provides us with an excellent demonstration of the process.

Résumé

Les défis soulevés par un monde postindustriel incitent à lancer des initiatives visant à commercialiser le patrimoine en tant que mythologies édifiées, divertissements populaires, tourisme et développement économique. Un mélange de nostalgie pour un passé imaginé, une insécurité culturelle et économique, et une demande croissante pour la consommation de divertissements ont fait d'un engagement aux multiples facettes avec le passé l'objet d'une politique économique. Que se passe-t-il ? S'agit-il d'un regard nostalgique sur le passé au fur et à mesure que nos vies et les endroits où nous vivons perdent leur caractère distinctif dans des morphages mondialisés d'une monotonie prévisible ? S'agit-il d'une « commercialisation des lieux en des temps qui n'ont pas de lieux » en guise de stratégie économique de la fin de l'ère industrielle ? De toute évidence, la formation du patrimoine est un processus dynamique, et la commercialisation très réussie des tunnels de Moose Jaw en constitue un parfait exemple.

Past

1 Memory — both individual and collective — is a pliable thing. This is what Julian Barnes had to say about it in England, England:

And like memory, the current engagement with the past has seen formal academic "History" being manipulated, transformed, and re-presented.

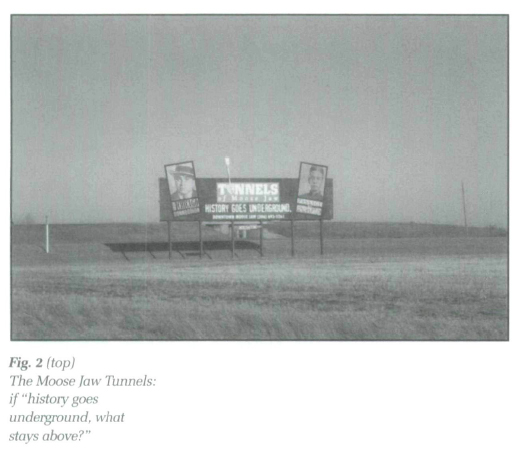

2 It has always been thus. History has always been appropriated by nationalist ideologies, drama, and romantic fiction: just consider Shakespeare, state-approved textbooks, the hours of CRB/Historica "Heritage Minutes," and "The Story of Canada." And apart from the cultivation of such hegemonic metanarratives, there's the appropriation of heritage as spectacle and consumer product: the first Roman "tourists" must have been guided around the sights of Pompeii soon after the dust had settled and the lava cooled! However, it's getting more complex as the challenges of a post-industrial world are prompting new initiatives. Increasingly, "heritage" is now discussed in the context of constructed mythologies, popular entertainment, tourism, and economic development. What history has always been to national identity, so heritage is now to "social cohesion" and economic vitality. A combination of nostalgia for an imagined past, economic and cultural insecurity, and a growing demand for the consumption of entertainment has made a multifaceted engagement with the past the stuff of heritage (Fig. 1). In Canada, this can be seen in an array of theme parks, ghost tours, romanticised murals, and "historical" re-enactments and displays.3 It is the conjunctions of informal memory and nostalgia, history and heritage, and public demand and commercial ingenuity that prompted Lowenthal to comment that,

What's going on?

3 To some extent, the rear-window gaze might be a nostalgic one in reaction to a growing sense of anomie — or at least discombobulation! — as our lives and places lose their distinctiveness in globalized morphings of a predictable sameness. Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being prompted one scholar to comment on the apparent verisimilitude and ephemerality of a modern world experiencing ever-increasing time-space compression:5 "Everything that occurs threatens to pass away so quickly we are not even sure whether it really happened. We are even less sure if our perceptions are shared, a collective phenomenon, or purely individual sensations."6 Paradoxically, the past may be a "foreign country" for some, but for others it is more familiar, secure, and tangible than the insecurities and uncertainties of the present and future.7 As a consequence of this longing—together with increased affluence and leisure time—western society has witnessed a tremendous growth in tourism and "place marketing in placeless times."8

4 As the title of his book Consuming Places implies, John Urry relates tourism and heritage to the commodification of distinctive locales and experiences. Central to the consideration of tourism as a form of consumption are the "interconnections between modernity, identity, and travel and the significance of heritage...in the making and remaking of place."9 In unpacking what he calls the "complex and inchoate" nature of tourism, Urry privileges the importance of the tourist "gaze," which requires that tourists "look individually or collectively upon aspects of the landscape or townscape which are distinctive, which signify an experience which contrasts with everyday experiences."10 It is a phenomenon that involves leisure from work, movement, temporary residence, constructed expectations, and well-established symbolic associations. More importantly, Urry argues that "tourist professionals,"

5 In fact, the past is increasingly being regarded as a "heritage industry," or a "quarry of resource possibilities from which heritage products can be created."12 Continuing the economic metaphor, history has been "mined for images and ideas that can be associated with commodities," it is being "bought and sold," and "remolded and shaped to serve the fickle demands of the market":

6 From such perspectives, the direct economic impact is measured in terms of jobs, business profits, and employment incomes in heritage-based enterprises. But there is also an indirect spin-off for communities that develop their heritage potential: they are often viewed as attractive places by other industries seeking new locations.14 Not surprisingly, therefore, many communities in the twenty-first century are evaluating their tourism and heritage potential — especially those seeking economic strategies to replace former industries and commercial activities disrupted by global economic restructuring. That is, the growth in tourism may be seen as "just one part of the two-century-old shift in the economy from goods to services, which tend to be labor intensive rather than raw material or goods intensive."15

7 But if the strategy of developing heritage-as-economic multiplier is clear, the actual approach to marketing heritage is problematic, and perhaps the most pressing issue is the matter of authenticity. While it may be argued that all heritage tourists are interested in escaping present realities—or at least immersing themselves in the past — two motives may be identified: "escape to reality" and "escape to fantasy." The "heritage realist" is "highly sensitive to the perceived authenticity of the object or the place and is repelled by what is experienced as contrived heritage." The "heritage as fantasy" consumer, however, turns to the theme parks, role-playing in banquets or battles, or sing-alongs and other forms of group participation in a nostalgic reaction to modernity.16 Provocatively, Urry argues that this form of "heritage-tourism" is supported by another category: "post-tourists" who are satisfied by "staged authenticity" and "delight in inauthenticity" — and even fantasy — for a good reason: they know that "there is no authentic tourist experience. [Authenticity] is merely another game to be played at, another pastiched service feature of postmodern experience."17 How else can we explain the tremendous success of the contrived fantasias in Disneylands, Disney Worlds, and other theme parks world-wide?18

8 Baudrillard takes the issue of authenticity a theoretical step further from the "real," through the "neo-real," to the "hyperreal" of the "simulacrum," his premise being based on a text from Ecclesiastes: "The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth — it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true."19 He then articulates the successive phases of the representation of the images: the reflection of a basic reality; the perversion of a basic reality: the masking of the absence of a basic reality; no relationship to any reality. The latter is what he calls the "pure simulacrum": no longer the simulation of something, nor the dissimulation of something — the strategy is of dissimulating that there is nothing! He explains:

9 Some would argue that such discussions resonate more with the "metaphysical than practical exercise" and that we would be better advised to,

10 It is in this context that this paper now turns to Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan: a place where economic restructuring turned to the imaginative marketing of the past, in the present, to make a distinctive place — and also economic revitalization. The Moose Jaw tunnels and their mythic former denizens are a good example of this (Fig. 2). They may serve as a mirror to examine how our contemporary values are reflected in them. Are they history, heritage, fantasy, theatre — or a simulacrum of contemporary discourses? The answer to these questions will serve to demonstrate the ways by which the past is being appropriated in our contemporary world, and to what end. Certainly, it needs to be better understood.

Moose Jaw: A Search for New Directions

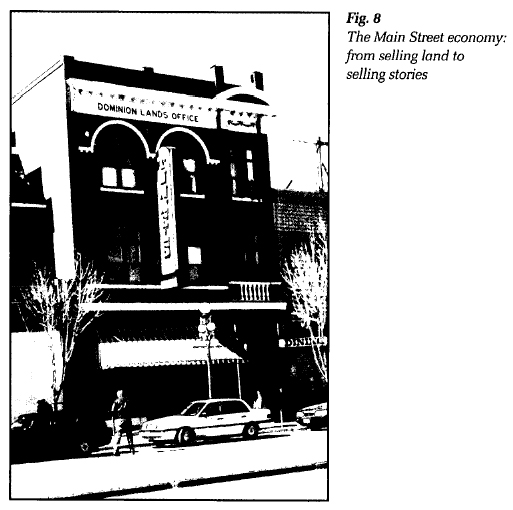

11 Moose Jaw's Euro-Canadian history is a microcosm of that of the Prairie West.22 Successively, the Dominion Land Act, the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Riel Rebellion, the Laurier-Sifton immigration, grain and cattle exports, and the Great Depression were landmarks in the first fifty years of its history. Registered as a town in 1881, passenger rail service commenced in 1883, and Moose Jaw was formally recognized as a city in 1903. Gradually, tents and wood-frame structures gave way to impressive brick structures that reflected its prosperity and regional prominence as wholesale distribution centre, processor of agricultural products, and a junction of railroads to the east, west, and south (Fig. 3).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 In recent years, Moose Jaw has seen a decline of its resident population from 33 593 in 1991 to 32 973 in 1996, although the city currently boasts of a recent population surge to 34 236 in 2001. It has also experienced significant economic restructuring. The long-standing economic sectors of agriculture, mining, construction, oil and petroleum, and manufacturing are all under pressure. In particular, 2001 is expected to be an especially hard year for Saskatchewan farmers facing drought and rising fuel and fertilizer costs, and the local Regional and Economic Development Council are predicting that net farm income for 2001 will be 63 percent less than the last five year average. As with other communities facing the erosion of their traditional economic base, Moose Jaw is now moving into a service-based economy. Accommodation, food and beverage services, sales, recreation, and cultural attractions are emerging as leading sectors in Moose Jaw employment.

13 In particular, there has been much growth associated with the tourism industry, most particularly in historically based attractions and adventure tourism, to the point that it is the fourth largest economic sector in Saskatchewan, generating $1.14 billion. Moose Jaw has shared in these developments and investment in tourism has resulted in an average annual increase in visitors of 35 percent since 1996 and current plans call for an increase of its present capacity of 230 hotel rooms by the addition of another 150 over the next three years. In line with this, the city recently announced an ambitious development — the $47 million "Project Moose Jaw" — that integrates several initiatives in the tourist trade. Perhaps the most successful thus far has been the Temple Gardens Mineral Spa which is now the city's ninth largest employer, with 153 full-time and part-time staff. It has attracted 400 000 visitors to the city since it opened in 1996 and an $8.2 million expansion will add another 86 rooms to the facility. Other plans call for the investment of $7.3 million in a 450-seat Culture Centre, a $13 million downtown Casino that will employ 120 personnel, the revitalization of the old part of town, a Regina-Moose Jaw historical-train link, walkways, and condominiums. According to Melody Nagel-Hisey, president of the southwest Saskatchewan tourist region, Moose Jaw tourism is held up as an economic model for the rest of the region.23 Her assertion is underpinned by the estimates that tourist spending in Moose Jaw amounted to $20 million in 1998, an increase of a third since 1996, with projections for the future of 150 000 visitors a year.

14 An important element in Moose Jaw's past performance and future expectations has been the remarkable exercise in heritage-ingenuity: the "Tunnels of Little Chicago" attraction. To a coal-miner, there's nothing romantic about tunnels!24 For tourists, however, these subterranean realms become intriguing when they are dramatized with stories acted out by a cast of intriguing characters. This is what happened at Moose Jaw. It is a process that bounces between the economic imperatives of a dynamic chamber of commerce, historical fact, and tourists' desires. Accordingly, it provides a remarkable case study of the materialization and performance of fantasy packaged as history and heritage. It provides a good example of how, as Robins puts it, "heritage, or the simulacrum of heritage, can be mobilized to gain competitive advantage in the race between places."25

An Emerging Strategy: Those "Muriels" on the Wall26

15 The tunnels weren't the first experiment with tourism. That honour goes to the idea of making the walls tell the story of a romanticised past. Moose Jaw's strategy of attempting to mitigate its recent economic decline by a series of dioramic murals has been well documented.27 In 1989, the city established a "Murals Committee" as part of the "Mayor's Task Force" on downtown revitalization. Others had gone this route before in Athens, Ontario, and Chemainus, B.C., the latter attracting 300 000 visitors and $26 million worth of business in 1991.28 With initial capitalization proposed at some $650 000 from various sources, 29 murals were painted between 1990 and 1996, with plans for the addition of two more a year until some 140 wall spaces were filled (Fig. 4).

16 How successful has the strategy been? Assuming 50 000 visitors annually, Widdis calculated a contribution of over $2 million to the local economy. But heritage-tourism needs to be appreciated in terms other than economics alone and Widdis also examined the Moose Jaw Murals in terms of the categories of authenticity, symbolic meaning, place-making, and commodification. His conclusion was that

17 While overall in favour of the murals, which he describes as a "flawed and yet worthwhile" project, Widdis was critical of die other heritage tourism initiative — die "tunnels" — as being "exploitative and false."30 What were the tunnels and how did they fit into Moose Jaw's heritage tourism strategy?

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5The Origins of a Myth: Discovering the Tunnels

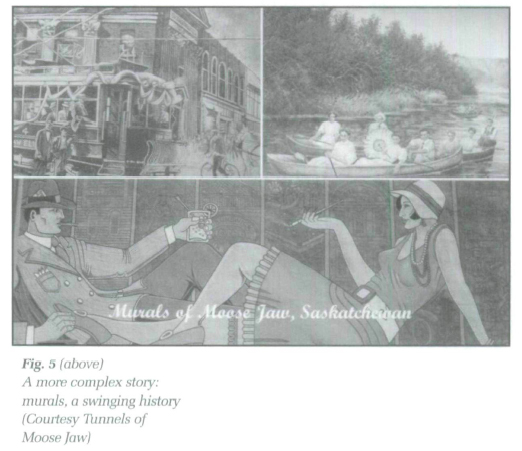

18 One of the Moose Jaw murals, "River Street Red," provoked considerable controversy (Fig. 5). Painted in 1991, it referred to a generally correct association of part of the town with activities that have not been unknown to society over the years: "cigareets and whiskey and wild, wild women"! As Moose Jaw grew in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the hotels and other establishments along River Street became associated with gambling, boot-legging, and prostitution. More particularly, it was claimed without any supportive evidence that American "hoods" from Chicago — including Al Capone himself! — were frequent visitors to, and sojourners in Moose Jaw. But how did all this relate to the tunnels?31

19 It all started with a collapsed manhole cover that appeared behind the Cornerstone Inn in the spring of 1985. Further investigation revealed a "fairly large brick-lined, bell-shaped area" that city workers declared was not part of the city sewer system. This somewhat prosaic event prompted reminiscences related to the seamy past of that part of town. In 1986, a local newspaper article announced "Tunnel Story in Moose Jaw Alive and Well" as a local researcher, Harvey Gallant, had uncovered evidence of former tunnels connecting several downtown establishments.32 Asserting that the "legend" of the Moose Jaw tunnels dated back to the 1930s when the city was "a centre for underworld criminal activity," it declared that Gallant "had found what everyone's been looking for." The list was impressive: bricked up and boarded up doorways that implied tunnels; archival evidence of people travelling through the tunnels; the remains of a still in a basement room; archival evidence of Al Capone's involvement in a Regina lawsuit. Others looked further afield and were disappointed later that year when the much publicised opening of "Al Capone's vault" in Chicago produced no evidence of a Capone-Moose Jaw connection.33

20 Despite these exotic tales, most probably a thorough scrutiny of contemporary architectural plans would have established that the supposed "tunnels" had had more utilitarian functions as storage areas, utility conduits, or basements. But the story was a good one.

The Search for Authenticity: The Official History

21 As the rumours about tunnels and passageways continued to grow, in 1987 two local researchers were commissioned by Moose Jaw's Downtown Business Improvement District (BID) to better document the origins and past functions of the Moose Jaw tunnels. Extensive examinations of buildings adjacent to the collapsed manhole revealed nothing other than former coal cellars, furnace rooms, foundation arches, and an abandoned "long and skinny" bowling alley, complete with a rear wall numbered one to eight. The one provocative find was a room located under the Brunswick Hotel. Entered by a trapdoor behind the bar, local folk-lore recounted stories of gamblers, mysterious Chinese messengers, and sliding walls.34 Others spoke of traversing mazes of tunnels occupied by, first, Chinese, and later, bootleggers, American gangsters — and even Al Capone. Yet another recalls her grandmother claiming that when she worked at the "Exchange Café" the "Chinese" would allow her to travel the tunnels to near to her home — to avoid the bitter winter winds of Saskatchewan.

22 This remembered-past certainly fitted in with what scholars knew of Moose Jaw's colourful official-history.35 At the opening of the twentieth century,

23 In particular, River Street constituted "the city's sinful, seamy underbelly." An array of establishments such as the "Savoy Café," the "Paris Café," and "Yip Foo's" restaurant variously offered opium, poker games, and harlots. Others like the "Elk Billiard Parlour," the "Colonial Billiard Parlour," "D'Jazz Pool Hall," "Riley's Pool Room," the "Cecil Pool Room," the "Veteran's Billiard Parlour," the "Russell Pool Room," were all fronts for gambling and bootlegging. And then there were such seedy dance halls such as "The Academy" (also known as the "Gonorrhea Race Track"), while several of the hotels along the north side of River Street—the "Alexander," "Qty Hotel," "The Brunswick," "The Empress," "The American," and "The Plaza" — were home to the "Bad Girls of Moose Jaw."37 From 1905 to 1927, all of this was overseen — if not nurtured — by the corrupt Chief of Police, Walter Johnson, who figures prominently in the River Street mural. All of this was substantiated in newspaper references to "Chinese opium dens"38 and a "place of prostitution in the heart of the city [frequented] by some prominent businessmen."39 Newspaper reports in the 1920s spoke of a "common bawdy house,"40 raids on "gambling places,"41 raids and arrests relating to illegal trade in liquor42 such as the "$1 500 worth of Moose Jaw booze...confiscated from James Kennedy of Montana."43

24 However, after considerable archival research, interviews, and field work, the research team concluded that there was "no conclusive evidence that tunnels do exist," but that there was "enough truth in the stories to warrant further investigation." In order to "definitely prove or disprove the rumours," they recommended professional excavations at the Brunswick Hotel, the Simington Block, and the Cornerstone Inn. Accordingly, BID applied to the Canada-Saskatchewan Tourist Agreement for funds for further study and argued that the "first step in the marketing of Moose Jaw's colourful history as a major tourist attraction will be underground."44

Surrender to Fantasy: "Constructing" the Tunnels

25 Over the ensuing months, while no firm evidence of the enigmatic tunnels emerged, the search continued under the Empress Hotel and various people claimed to have discovered traces under their own homes, or remembered them elsewhere throughout the community.45 Increasingly, however, the public debate moved away from the issue of authenticity and focused more on the optimal contribution of the tunnels to the city's much needed economic development.

26 Not surprisingly, imaginative developers were not averse to closing their eyes to the absence of material evidence, focusing more on the patchwork of memories, and marketing their own explanations. Increasingly, the plans for a heritage-tourism initiative were crystalizing around several narratives that centred on the putative tunnels.

27 It was claimed that they were used as bolt-holes by illegal Chinese immigrants avoiding Canada's pernicious "head taxes" and even for smuggling in illegal immigrants. One person maintained that they had been built by Chinese around 1908 and connected the CPR Station, the old Exchange Café, and the Brunswick Hotel.46 Another remembered seeing people, "mostly Chinese," coming out of a hole in an alley between River and Main Streets at the time of a fire in a boarding house in the 1940s.

28 Another theme that emerged was that the tunnels had been used as routes for the surreptitious movement of gambling chits and contraband liquor. In 1990, demolition of a house on River Street revealed a tunnel together with an empty 1920s-style liquor bottle from Costa Rica and a wooden rum-bottle case: these were taken as evidence of contraband goods and prompted the search for a Capone linkage.47 Evidence of other tunnels emerged as the construction of the Spa project went ahead on the site of the former Harwood Hotel, and while historians recognized the new finds as mere basement storage space, others favoured a more unsavoury interpretation as "[w]ithout too much embellishment, there were some pretty raunchy characters around here."48 While some doubted that Capone had ever crossed the Canadian border,49 there were those who nevertheless argued that the tunnels were hideaways where Chicago villains—even Al Capone—could escape from American justice. Whatever the evidence, the central argument was that the Capone-mob connection provided the right story line for interpreting the tunnels.

29 The central parameters had been aired back in 1993.50 At that time, Mayor Don Mitchell had bemoaned the development, arguing to city council that "It may be in the American tradition to build tourist attractions on the false promises of history" and suggested that the heritage tourist strategy should stick to the facts and focus on realities of the former activities on Moose Jaw's River Street. But local author June Russell disagreed: "Finally Moose Jaw has within reach a rich tourist drawing card...tourists eat that stuff up and Moose Jaw can certainly do with any boost." The Rubicon had been crossed, and the "construction" of heritage took on a new meaning.

30 At least one local entrepreneur had early recognized the commercial potential of the story-cum-myth that was emerging. In November 1994, Bernie Dombowsky added a "Tunnel Parlour" to his establishment, "Charlotte's Restaurant," and prompted nationwide news coverage.51 The following year, the chamber of commerce moved towards some form of formal recognition of a "tunnels initiative" and, in September 1995, a "Tunnel History Committee" commenced its deliberations.52 The following month, a Moose Jaw delegation announced its plans to travel to Montana to investigate their tunnels with the intention of examining how to set up tunnels as a tourist attraction.53

31 But a division was emerging.54 On the one hand, a private business group, "The Tunnels of Little Chicago Association Inc." (TOLC), wanted to establish a commercial enterprise to develop tourism and, to that end, sought a tax deduction.55 They were opposed by the "Old Town Tunnels" group, a non-profit organization connected to the city's Business Improvement District (BID). The "Tunnels of Chicago" group picked up the momentum with a gala-banquet at which they introduced the public to the "characters" who would be part of the guided tours and announced their intention to coincide their opening with the city's other foray into tourism — the Temple Gardens Minerals Spa.56 In an attempt at nurturing public support—and investment, albeit a modest one—the TOLC started selling $50 memberships and announced plans for a five year plan to "reconstruct" the tunnels in eight stages. Soon after this well-orchestrated and well-received event, the "Tunnels" were being touted as the focal project in the revitalization of downtown Moose Jaw.57 Capitalizing on the "history and folklore" of south Main Street, the intention was to create a theme of the roaring 1920s centred on the CPR station and the "legendary tunnels." For Michael Dombowsky, the TOLC project manager, the history of the Moose Jaw area was "unlike that of any other city in Western Canada" and an ideal catalyst for downtown rejuvenation: "We're creating something that's special and specific to this community. We are creating time travel."58

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 632 By the spring of 1996, it was clear that the "Tunnels of Little Chicago" had taken control of the concept. Their "ambitious project" had grown to include two tunnels, renovations of the CP station, storefront development, tunnel links across Main and River Streets, and the restoration of Joyner's department store and its "famous cash trolley system."59 By high summer, the workers were racing to finish the project in time for the local celebration, "Sidewalk Days," but it wasn't until mid June that the public were given a preview of the completed project.60 On 15 June, the Moose Jaw Times Herald reported the official opening with the Mayor doing the honours by snipping a lady's garter-ribbon, while the hitherto contestation of the interpretive theme was forever put to rest by the presence of Al "Scarface" Capone, attended by "a lithesome moll and a short man with a bulge under his left shoulder." Despite the weight of history, Al Capone had finally come to Moose Jaw (Fig. 6)!

Fantasy Reified: Choreographing the Tunnels

33 But there were still those who were critical of the general lack of authenticity and the particular issue of the imputed Chicago connection. In July 1997, in an article that got right to the core of the problem of commodification of history for the sake of local profit, the TOLC was accused of presenting a "Disneyfied" and rose-coloured version of Moose Jaw's past.61 Through omission and selectivity, "we scrub clean our gamblers and bootleggers. We package them as quaint, and sell them to the tourists." The "uncut" history of Moose Jaw was said to be "not pretty":

34 The "tourist versions of history" were notable for their elisions: the tours of the tunnels focus on gambling and bootlegging and omit references to prostitution, "an essential corner of the triangle of vice"; the tragic history of the illegal Asian immigrants kept as underground slaves by Moose Jaw businessmen is glossed over; a pool hall is named after a gangster who was "an evil murderer and probably a psychopath" (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, the TOLC was commended for an initiative that has generated a "growing tourism trade" that benefits many other businesses. The conclusion was clear: "It's good business to tell tales to tourists," but with the telling caveat and theoretically significant warning, "It's only dangerous if we start believing it ourselves." This was the thesis that was coming to dominate the development discourse. Arguing in favour of a pro-active approach to selling place, the writer queried, "Do the host cities of the Loch Ness Monster and the Ogopogo go out of their way to disprove their local legends? You can bet they don't. We shouldn't dig too hard for the truth behind the tunnels. The answer we might find might dispel a romantic past that makes Moose Jaw a colourful city to live in and visit." As far as this person was concerned, if appropriate tunnels couldn't be discovered then the developers should build some!62 And this is exactly what the TOLC proceeded to do (Fig. 8).

35 Within months of their opening, the "Tunnels" were proving to be a popular attraction with 5 000 visitors in the first two months of operation and a symbiotic benefit being experienced by the other new venture, the Temple Gardens Mineral Spa complex.63 By year's end, the "Tunnels" had accommodated some 15 000 visits in its first season with a peak staff of ten persons,64 and on their first anniversary, the local newspaper bruited abroad, "Happy Birthday Tunnels," declaring that their popularity had surprised even their organizers.65 Tourists were coming from 28 countries, 10 provinces, and 28 states in the United States66 and, by May 1999, the organizers were promising their 50 000th visitor soon.67

36 But the TOLC experience with the first years of the tourist development had demonstrated that economic success required an enhancement of the facilities and further embellishment of their storied past. In 1997, a "Tunnels A-Maze-Ments" exhibition with mannequins developed the theme of the "wets versus the dries" in the Prohibition, Michael Dombowsky arguing that "It's one of the ways that private business people in the city are working to tell the history of the city."68 The following year, attention was directed to developing the former Moose Jaw Drug and Stationary Building into a tourist attraction linked to the "Tunnels."69 In 1999, the "Chicago Tunnels" could boast 77 000 visitors and announced a new expanded tunnel to be called the "Chicago Connection," with a focus on Al Capone, Penny Eberle arguing that "We've done a lot of research on this, the Al Capone connection, the diamond Jim Brady connection, his cohorts, the kind of security they had around them."70 This development marked a declared shift in emphasis. Noting that the earnings for the "Tunnels of Little Chicago Association" were up 54 percent since the 1997 period with visits peaking at 450 per day during the summer of 1998, a new strategy was initiated: it was to be "based on history but it's also going to be entertainment."71

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 937 The new plans and philosophy proceeded apace (Fig. 9). Early in 2000, it was announced that some $1.2 million was to be directed to constructing three new tunnels,72 prompting a local businessman to comment on his decision to relocate on Main Street, "I think the tunnels are the Industry that Moose Jaw has been waiting for for many years."73 Close on the heels of the announced expansion, the "Tunnels of Little Chicago" purchased land for the development of a 400-seat ampitheatre.74 With the city doubling its share, the TOLC increased its capitalization to $1.5 million and predicted it would attract 100 000 visitors annually. The Chicago Connection theme was now well established and the next planned development was the "Chinese Connection."75

38 Perhaps predictably, the growing success of the TOLC angered some local businessmen who, while appreciating the general economic stimulus downtown, felt they had been excluded from the venture.76 Nevertheless, the TOLC star was on the ascendant: the "Tunnels" were featured on TV;77 in August 2000, Six Canadians on a Bus (a reality-based television show to "Promote Canadian Pride") stopped in Moose Jaw to visit the tunnels78; finally, the ultimate accolade, Allan Fotheringham featured "Raunchy Old Moose Jaw" in his column in Macleans.79

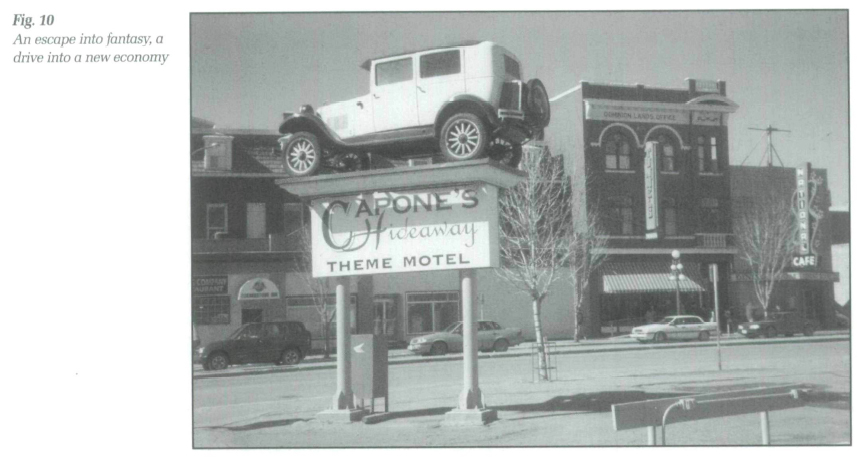

39 Moose Jaw was on the map and the Tunnels of Little Chicago were a success. And interestingly, despite all of the hullabaloo about "real" history and fabricated heritage, people were flocking to Moose Jaw for both learning and entertainment: for one tourist, "I didn't know too much about the Chinese immigrants. I wanted to learn more about the historical side of things. I was surprised to see how poorly they were treated in the Prairies, too."80 Whatever the trappings of fantasy, history and heritage were being delivered too — and it was hard to disbelieve with the ubiquitous visual prompts and materialisation of history in Moose Jaw's townscape (Fig. 10).

Conclusion

40 In Jane Jacobs' Edge of Empire, she discusses how cities "reinvent" themselves in their development of "new tourism," they are "sites in the process of becoming," sites saturated with the cultural politics of transformation, influenced both by the global and the local.81 She proposes that heritage-making "is a dynamic process of creation in which a multiplicity of pasts jostle for the present purpose of being sanctified as heritage":

41 This is what is happening in Moose Jaw. Serious minded academics preoccupied with authenticity and veracity might be disturbed by the appropriation of foreign themes in an unabashed entrepreneurial initiative that manufactures and commodifies history.83 But think of it as theatre, not heritage. Stratford has its Shakespeare. Niagara has its Shaw. Moose Jaw has Al Capone. Whatever the differences in cultural product, the economic initiative is the same.

42 And, in some ways, it's also a process of "making" history. As John Walton has argued, history is two different things at once: the objectively known and consensually agreed upon historical reality of facts, events, and values; and a more subjective history that is constructed in the stories of what is said to have happened, or even imagined to have happened in the past.84 Referring to what "common people carry around in their heads" as "public history," Walton goes on to say that public history is often tied to a pragmatic agenda directed to such presentist aims as social reform, political reorganization, or economic transformation, and concludes that such narratives are necessarily facile, selective, and "sometimes pure invention."85 However, myth, even fantasy or make-believe, can become heritage, especially when acted out over time with the sufficient expenditure of collective action — and a barrage of material prompts. Certainly, one "historical" verity is that, hereafter, thousands of visitors will always associate Moose Jaw with a distant past of crime, vice, and racial injustice, and there is some truth to this — even if Al Capone never slept there. Indeed, does it matter whether he did or not?

Postscript

43 In May 2001, the Tunnels of Moose Jaw were awarded an "Attractions Canada Award" in the category of "Leisure/Amusement Centres."86 As a spokesperson pointed out, it was "a feather in the cap for the tunnels, as well as for Moose Jaw and the province."