Articles

The Park in the City:

Baseball Landscapes Civically Considered

Abstract

Baseball parks are among the few buildings that survived the creative destruction that swept through American cities in the twentieth century. Accommodating public ritual, shaping public space, and responding to the surrounding city, the classic ballparks built between 1909 and 1923 promoted civic consciousness. The recent destruction of the classic ballparks has occasioned anger and anguish. Yet nothing has slowed the pace of destruction, as only two of the fourteen classic ballparks remain. Despite the opposition of baseball fans, team owners and public officials continue to find reasons to destroy the classic ballparks. The newest ballparks, the "rétros," products of political alliances between private and public elites, have little to offer the city or the average fan. The history of baseball landscapes thus illuminates the decline of public places and spaces and the closely-related decline in social equality and the atrophy of public opinion as a governing force.

Résumé

Les stades de baseball comptent parmi les rares installations à avoir survécu à la frénésie de destruction créatrice qui a saisi les villes américaines au XX siècle. Typiquement américains, propices aux rituels collectifs et sources de fierté civique, les stades classiques construits entre 1909 et 1923 ont favorisé la conscience communautaire. Si différents des stades des années 1960 et 1970 inspirés de la banlieue, les stades de baseball classiques répondaient à la ville qui les entourait, liant parc, emplacement, quartier et ville. La récente démolition des stades classiques a suscité de la colère et un sentiment de dépossession chez les gens. Mais rien n 'a ralenti la cadence de la destruction et seuls deux des quatorze stades classiques subsistent. Malgré la vive opposition des amateurs de baseball, les propriétaires d'équipes et les pouvoirs publics continent de trouver des raisons de détruire ces stades. Les nouveaux stades « rétro », produits d'alliances politiques entre les élites des secteur privé et public, ont peu à offrir à la ville ou aux amateurs moyens. L'histoire des lieux du baseball met ainsi en lumière le déclin des places et lieux publics et de l'égalité sociale concomitante et l'atrophie de l'opinion publique en tant que force vive d'une république.

1 American cities are notorious for destroying and remaking themselves at a furious pace. Returning to New York from self-imposed European exile in 1904, Henry James felt the "dreadful chill of change" in the physical disappearance of the buildings, the neighbourhoods, he had known. A generation later, in his pioneering studies of collective memory, Maurice Halbwachs asked how "can spatial memories find their place where everything is changed, where there are no more vestiges or landmarks?"

2 Memories are not only socially constructed (individuals telling and writing stories, sharing, celebrating, lamenting with others) but they were also physically constructed. Memories are the product of one's encounters with landscapes and buildings and are stored in those physical artifacts which then serve as stimulants to recollection. For James, the disappearance of physical landmarks was not just a matter of personal memory or nostalgia. If cities made history visible through their architecture, as Lewis Mumford later argued, then American cities threatened to make history invisible. James found the city "crowned not only with no history, but with no credible possibility of time for history." The encounter with landscapes and buildings shapes our image of the city and its history, making it more legible, and stirs our loyalty to place and our aspirations for it. The destruction of physical artifacts frustrates the development of civic consciousness.1

3 Only a few buildings survived the gales of creative destruction that swept through American cities for most of the twentieth century. Conspicuous among those buildings were the first generation of steel and concrete baseball parks built between 1909 and 1923. When James returned to New York in 1904, the ballpark at the north end of Manhattan Island, the Polo Grounds, had already become a local landmark. Nested into Coogan's Bluff, the Polo Grounds had hosted baseball games since 1890. In 1911 it would burn and be rebuilt. The new Polo Grounds became a civic landmark, treasured precisely for its longevity. Instantly identifiable by its horseshoe shape, the Polo Grounds would please baseball fans until its destruction in 1964, hosting such memorable moments as the Merkle "boner" (1908), Bobby Thomson's "shot heard round the world" (1951), and "the catch" by Willie Mays (1954).2

4 Like the great railway stations, civic centres and City Beautiful parks and monuments of the time, the classic ballparks focused civic pride and promoted civic consciousness. Connecting past and present, the ballparks provided a sense of place and shared memories of heroic exploits and monumental blunders. No wonder the destruction of these ballparks has occasioned so much anger and anguish. Yet nothing has slowed the pace of destruction, as only two — Wrigley Field in Chicago and Fenway Park in Boston — of the fourteen classic ballparks remain and Fenway is seriously threatened. The latest to fall was Detroit's Tiger Stadium, where three-fourths of the members of the Hall of Fame had played. Creative destruction has come to baseball with a vengeance. On average, one new major league baseball field* has opened per year since 1989 as even the many stadia built in the 1960s and the 1970s are being demolished.3

5 Whether you are a baseball fan or not, the history of baseball landscapes **illuminates the decline of public places and spaces. The urban ballpark is a uniquely American building, accommodating a public ritual and stimulating civic pride. The best of these structures use public space to shape the city on a grand scale. So unlike the suburban-inspired stadia that followed, the urban ballparks respond to the city around them, linking park, site, neighborhood, and city. Baseball fans knew what they had. No "building type commands more allegiance," the Architectural Record estimates, "than the early twentieth-century ballpark." Yet, despite the passionate opposition of many baseball fans, team owners and public officials continue to find reasons to destroy them.

6 The disappearance of these classic ballparks amount to what architect John Pastier calls our "greatest failure" in historic preservation. The classic ballparks are now being supplanted by the "retro" parks that superficially honour the classic form but are more like baseball "theme parks" for the rich. Consider what appears to be the main entrance to the new Comiskey Park that opened in 1991 at the corner of 35th and Shields in Chicago. Superficially reminiscent of the grand entrances of the classic ballparks that created lively public spaces, the entrance is engraved with the words "Comiskey Park" and seems to invite the baseball fan to enter the structure his or her taxes have built. But the entrance is exclusively for team officials, the public officials responsible for the park's construction and those in luxury suites.4 Such developments suggest a great deal about the political alliances that are building these baseball fields and the reasons they often have so little to offer the average fan. The history of baseball landscapes thus not only suggests the decay of our public spaces but also the closely-related decline in social equality and the atrophy of democratic public opinion as a governing force in the republic.

The "Park in the City"

7 The essential quality of the classic ballpark was that it wove green and public spaces into the city's fabric. While clearly an urban structure, the field also remained a grounds. The visual impact of the Polo Grounds, for example, was vastness. The expanse of the playing field was an enclosed vastness, the field surrounded by the grandstand and the city beyond. The Polo Grounds, historian G. Edward White writes, symbolized the "bright, expansive, reassuring, open-air features" of the early twentieth-century city, not its "dark, cloistered, dangerous, industrial features." Linking elevated trains, large crowds, and a massive structure with the surrounding bluffs, the Harlem River, and surviving meadows, baseball at the Polo Grounds celebrated the march of the city up the lush island of Manhattan. When New Yorkers paused in 1911 to "take a fresh breath and brag about the 'biggest baseball yard in the world'," they found that the ballpark created a large amphitheatre that afforded excellent views of the surrounding landscapes of buildings and natural features. Ebbets Field, the Brooklyn Eagle editorialized when it opened in 1913, also "offered unusual opportunities for an extensive view of the borough and its suburbs," setting off nearby parkways and neighbourhoods to good effect. The ballpark also ensured that green, open space, the focus of the event that attracted the crowds, would not disappear from the city. Injecting green, open space into the heart of the city, the urban ballpark transcended the either/or of city/country.5

8 Baseball's quality of juxtaposing the city and the country is famously celebrated. Evoking pastoral associations — spring training, fall classic, green fields — the game was popularized by ambitious artisans and clerks from the big city, who wielded the artifacts of the urban crafts (bats, balls, gloves; woodworking, needle trades, leather working) and were eager to exploit the sport commercially. This quality extended to the baseball field itself. The hands-on instructions for laying out a baseball field from the 1867 Beadle's Dime Base-Ball Player combined the skills of the farmer and the city builder. "In selecting a suitable ground," the guide (written by Henry Chadwick) explained, "there are many points to be taken into consideration. The ground should be level, and the surface free from all irregularities, and, if possible covered with fine turf; if the latter can not be done, and the soil is gravelly, a loamy soil should be laid down around the bases, and all the gravel removed therefrom." The ground having been prepared, the geometry could be laid out. The guide retailed a technique city builders employed for laying out a foundation: "take a cord one hundred and eighty feet [55 metres] long, fasten one end at the home base, and the other at second, and then grasp it in the centre and extend it first to the right side, which will indicate the position of the third; this will give the exact measurement, as the string will thus form the sides of a square whose side is ninety feet [27 metres]."6 Rural and urban modes of construction, of approximation and precision, feel and measurement, are embedded in the game.

9 This is echoed in the geometry of the field. Unlike the football field, basketball court, or hockey rink, the baseball field is both precisely determined and indeterminate. The infield and foul lines, the distance and angle between the bases, the strange five-sided home plate are all based on precise measurement but the amount of foul ground where pop flies are turned into outs and the distances to the foul poles and outfield walls is flexible.7 "Squares containing circles containing rectangles," Bart Giamatti wrote of the baseball field, "precision in counterpoint to passion; order compressing energy." Rectangular batter's box and pitcher's rubber sit inside the dirt circles, which sit inside the infield diamond, which sits inside the semi-circle created by the edge where infield dirt meets outfield grass, which sits inside the larger half diamond extended outward along the foul lines, which sits inside the semi-circle created by the outfield fence from foul line to foul line, which sits inside the city block on which the ball park is built, which sits inside the city as a whole. At the center of game and field is the "curious pentagram," home plate whose "irregular precision" organized "the field as it energized the odd pattern of squares tipped and circles incomplete," expressing the combination of "boundary and freedom" that is essential to the game. The baseball field, Giamatti concluded, evokes paradise, an "enclosed, green place" of the Edenic myth. But at the same time, Giamatti links the baseball field to urbs and polis, the political and culture-making elements of city life.8

10 The recent documentary Forever Baseball more simply describes the baseball field as "a geometrically perfect landscape."9 A combination of rural expanse and urban artifact, the baseball field and the park in the city in which it was embedded spoke to a central problem in American culture. A terrifying image insistently surfaced in the nineteenth century: the machine in the garden. Inheriting a European dream of a pastoral harmony with nature, and transforming it into a social and political theory of the middle landscape and the yeoman's republic, Americans were troubled by the intrusion of machine technology into the landscape. Our literature, as Leo Marx has beautifully shown, is filled with disturbing images of the trains, steamboats, furnaces, and cities of ash defiling a once pristine landscape. Could Americans establish an urban and industrial civilization, these images asked, that was based on a sustainable relationship to nature?

11 The park in the city represented the beginnings of an answer and counter image to the machine in the garden. In a 1938 promotional film, an unreliable work of undeniable imagination, the National League of Baseball Clubs offered a revealing image of baseball's relation to city and country. Combining the Abner Doubleday myth of baseball's 1839 immaculate conception in pastoral Cooperstown with a fractured account of Alexander Cartwright's actual codification of the rules in 1845, the vignette opens with Doubleday and Abner Graves in a pasture teaching boys to play baseball. (An elderly Graves's recollections would later provide the only "evidence" for the claim that Doubleday "invented" baseball.) Doubleday's game is not working; the bases are too close together. Graves explains: "What you need is an engineer.. .You know the essence of this game lies in the relation between the distance for the runner and the speed of the ball." The "documentary" then explains (over the image of a technical blueprint) that six years later a young "civil engineer," Alexander Cartwright, "scientifically established the base lines." Cartwright was actually a bank clerk, but the story captures baseball as wish fulfillment, as the product of an urban intellect that remains in harmonious touch with its pastoral bearings.10

12 Integral to the landscape of baseball, the park in the city is also the foundation of landscape architecture. The association of baseball with landscape architecture links it to the most promising response to the greatest problem of American civic life, the encounter with nature. In discussing the legacy of pioneer landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Lewis Mumford stressed that city life did not, as we carelessly assume, lessen humanity's dependence on nature but elaborated it. Open, green spaces and a respect for nature, Olmsted's parks suggested, would civilize America's cities.11 At the same time the baseball field and baseball park were being designed, Frederick Law Olmsted was creating Central Park and embarking on a long career as a designer of urban parks. The same sense that the city was overwhelming the country that gave rise to the call for Central Park and for Olmsted's philosophy of parks was generating the mania for baseball.

13 In an era when innovations in construction and communication were allowing cities to enclose more activities than ever before, what should be understood as the great incarceration intensified the thirst for the great outdoors. In the 1850s, Porter's Spirit of the Times reported, every vacant lot "within ten miles of [New York] was being used as a playing field." When entrepreneurs began building fences and grandstands around baseball fields and charging admission, the baseball fraternity derided it as "the enclosure movement." But enclosure did not extinguish the park-like character of the baseball field. Turning William Cammeyer's Brooklyn skating rink into the first enclosed baseball field in 1862 required the same sort of landscaping skills (the Brooklyn Eagle reported on Cammeyer's "draining, leveling, sodding, and converting") that Olmsted's parks did and promised to serve some of the same civic and social purposes.12

14 The urban park, Olmsted argued, must provide "the greatest possible contrast with the streets and shops" of the business city. In the business streets, Olmsted explained, "to merely avoid collision with those we meet and pass upon the sidewalks we have constantly to watch, to foresee, to guard against their movement." We are therefore brought "into close dealings with other minds without any friendly flowing toward them, but rather a drawing from them." The urban park provided the "opportunity for people to come together for the single purpose of enjoyment, unembarrassed by the limitations" of their ordinary lives, "with an evident glee in the prospect of coming together, all classes largely represented, with a common purpose."13 Walt Whitman saw the baseball park fulfilling something of the same function. "It will take our people out of doors," Whitman wrote, "fill them with oxygen, give them a larger physical stoicism, tend to relieve us from being a nervous, dyspeptic set." When the Brooklyn Eagle reported on the opening of Cammeyer's 1862 revamped skating rink, the newspaper instinctively invoked Olmsted's Central Park. "At the Central Park," the paper reported, "there are ball grounds on the same plan as those established here."14

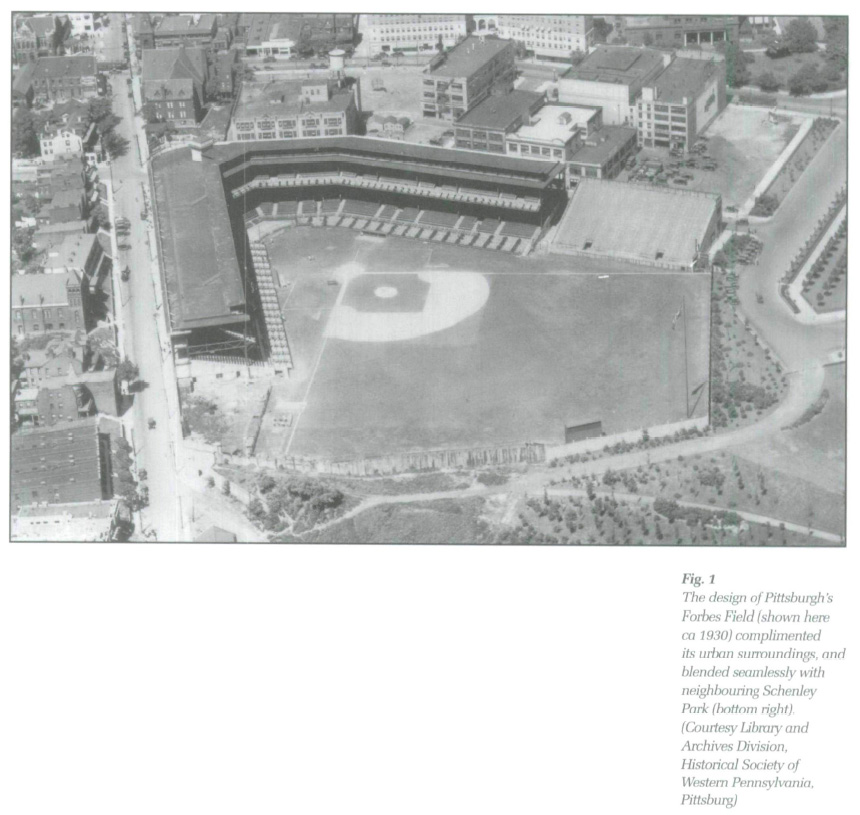

15 Olmsted's parks promoted a democratic culture aimed at elevating and educating the lower classes. The urban park, he wrote, would exercise "a distinctly harmonizing and refining influence upon the most unfortunate and most lawless classes of the city," encouraging in them "courtesy, self-control, and temperance" while weakening their "dangerous inclinations." The Eagle similarly found Cammeyer's park "a suitable place for ball playing, where ladies can witness the game without being annoyed by the indecorous behavior of the rowdies."15 While Olmsted was insisting to a parsimonious and skeptical nation that a judicious public investment in parks would help civilize the city, baseball parks were realizing some of his hopes.

The Civic Ideal Made Real

16 After Cammeyer's experiment, the enclosed ballpark became more and more prevalent, providing the essential foundation for the commercialization and professionalization of the game. The urban ballpark would find its classic expression early in the twentieth century, when the first steel and concrete parks replaced the wooden ballparks of the nineteenth century. "Just as the monumental cathedrals which everywhere dot Europe are the expression of the ideals and aspirations of mankind," the City Beautiful advocate Frederic Howe argued at the height of the Progressive era, "so in America, democracy is coming to demand and appreciate fitting monuments for the realization of its life, and splendid parks and structures as the embodiment of its ideals."16 The classic ballparks appeared to fit the bill. "Is there any other experience in modern life," philosopher Morris Cohen asked in 1919 after visiting one of the new ballparks, "in which the multitudes of men so completely and intensely lose their individual selves in the larger life which they call their city."17 Cohen's question was rhetorical as a consensus had emerged on the civic value of the baseball park.

17 A visit to the ballpark, Outlook reported in 1913, promoted "social solidarity" and "due respect for lawful authority," providing a "safety-valve" of "momentary relief from the strain and intolerable burden" of city life.18 Journalists found democracy in the baseball crowd, with "some of the best-known business and professional men...standing side by side with their clerks and stenographers. There was a portly banker next to a ragged bootblack, a street-car conductor and an army officer." They praised the ballpark for accommodating a "democratic amusement" that brought together "the banker and the office-boy, the millionaire and the chauffeur, the professor and the laborer."19 "Business and professional men," Harpers Weekly reported in 1910, stand "shoulder to shoulder with the street urchin," cheering at the ballpark.20 The Atlantic Monthly praised the baseball park as our "national contribution to the building arts," housing "the religion of democracy" for crowds "made up of all conditions, ages, races, temperaments, and states of mind."21 Connie Mack was thus repeating a truism when in 1950 he recalled the "great democracy of fans in the grandstands and in the bleachers."22

18 The classic ballparks thus made real the civic ambitions of the City Beautiful movement. Heir to Olmsted's landscaping ideals, the City Beautiful movement sought to promote civic loyalty and good citizenship through inspiring physical artifacts.23 Daniel Burnham, a leader of the movement, argued that "good citizenship is the prime object of good city planning." Charles Mulford Robinson added that a beautiful city would be "more prideworthy ... more majestic, [and] better worth the devotion and service of its citizens."24 The owner of the Cincinnati Reds, John Brush, rebuilt his ballpark in the architectural image of the "White City," the centrepiece of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 and exemplar of the City Beautiful. Cincinnati's Palace of the Fans would influence the design of Comiskey Park, Shibe Park in Philadelphia, and other ballparks that copied the classical architecture promoted by the City Beautiful.25

19 Privately-constructed, the classic ballparks were certainly profit-oriented ventures. Brush included an early version of luxury boxes, deemed "Fashion Boxes," overhanging the dugouts. But the central feature of the Palace of the Fans was a classical pediment behind home plate engraved "CINCINNATI" in an appeal to civic pride. Barney Dreyfus, owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, insured that the design of Forbes Field (1909) would maximize premium-priced seats. But Forbes Field also provided an Ohnstedian "scene to make participants forget the business cares of a manufacturing city." The Reds banned advertising in their new park for fear of "spoiling" the appearance of the park and criticized other teams for defacing their parks just to "grab a few dollars." Dreyfus also banned advertising. Anxious to make his ballpark a civic institution, Charles Ebbets commissioned a massive rotunda, complete with marble floors and chandelier.26 Walter Briggs, the Tigers' owner in the 1930s, believed Detroit's autoworkers should have access to the games. His renovations of Tiger Stadium created two to three times the number of low-cost bleacher tickets than the average park and he started games at 3 p.m. to accommodate auto workers on the day shift. Briggs reportedly never took a cent out of the team, but reinvested it in park and team.27

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 120 The classic ballparks thus acknowledged the key City Beautiful tenet. The "city cannot maintain a high commercial standing," St Louis's City Beautiful plan put it, "unless it maintains, at the same time, a high civic life." As Howe put it in his praise of the City Beautiful, a belief in the city "as an object of public-spirited endeavor" had tempered the "earlier commercial ideals that characterized our thought." The key to linking commercial and civic success was integrating open space into the fabric of the city. Olmsted had explained that it was "a common error to regard a park as something to be produced complete in itself, as a picture on a canvas. It should rather be planned as one to be done in fresco, with constant consideration of exterior objects."28

21 The best of the classic ballparks had exactly this quality. Privately-built, they were often located in run-down neighbourhoods where cheap land could be found. Having made an investment in the location, the teams tried to repair and upgrade the area. Philadelphia's Shibe Park supplanted a recently-closed hospital for smallpox victims as the focus of its reviving neighbourhood. Philadelphia's mayor commented in his opening day speech on the residential and commercial improvement of the Shibe Park neighbourhood. Local realtors promoted adjoining real estate when Ebbets opened.29

22 Although the classic ballparks were "not generally shaped by landscape architects," Pastier writes, they "contributed to and grew out of the urban landscape."30 Forbes Field, which was in fact designed by a landscape architect, illustrates Pastier's point. Dreyfus located Forbes Field in Pittsburgh's Oakland neighbourhood, situated between a working-class residential area and the mansions of the city's elite. Already something of a cultural centre, the area supported two colleges, a museum, library, concert hall, conservatory, and the city's largest public park. Dreyfus's landscape architect, Charles Leavitt, worked with a lot dominated by a deep gully requiring extensive backfilling. Since most of the site was unsuitable for building, a ballpark with a grandstand on one edge and an open field elsewhere was the perfect facility to repair and complete the urban fabric. The park complemented and set off the site, the green of the field echoing the hilly Schenley Park just behind the field. From the outside, the park was a combination of structural steel painted green, a white terra cotta exterior, and a copper-sheathed roof that produced an orange glow. The park contributed to the vitality of the neighbourhood, where fans would stop in the Kunst Bakery before the game and linger for a beer after the game at Gustine's or other establishments within easy walking distance.31

23 The park that replaced Forbes Field occupies what potentially is the most spectacular civic site in the country. At the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers where they combine to create the Ohio, the enclosed, circular Three Rivers Stadium (1970) cut off the sounds and sights of the surrounding city as well. Blocking a view of the city's skyline and striking bluffs, complains a critic, the stadium "might as well be situated in the Mojave Desert." The urban renewal programs of the 1960s would demolish Forbes Field as the University of Pittsburgh coveted the real estate and the Pirates were eager to escape the costs of maintenance. Three Rivers Stadium would be cast as the crowning achievement of Pittsburgh's urban renaissance, but the long walking distance from downtown has never been overcome as an obstacle to integrating the Stadium into the city's fabric. Three Rivers Stadium was only one of fourteen new stadiums built in the 1960s and 70s. Built in a period when Americans had lost faith in their cities, the new stadia were oblivious to their sites, even when located downtown. Circular in shape, often covered by a dome, the new stadiums kept the surrounding city at arm's length, acknowledging and contributing to the deterioration of American cities.32

24 The classic ballparks became victims of the disinvestment in and resulting decay of America's cities. Although urban renewal was touted as a means of revitalizing the city, the lion's share of federal monies went to encouraging suburbanization. Public subsidies for interstate highways sped commuters to the suburbs while ripping apart the urban fabric for new traffic arteries. Meanwhile federal mortgage insurance almost exclusively targeted suburban residences. Receiving a much smaller share of funds, urban renewal tended to favour institutional expansion for universities and hospitals rather than the restoration of existing residential neighbourhoods. As more and more baseball fans left for the suburbs, the occasional return to the ballpark no longer invoked the possibilities of city life. Instead traffic delays, a scarcity of parking, and face-to-face encounters with the impoverished who made up an increasing proportion of inner-city populations reminded fans of all the reasons they had left the cities in the first place. Overconfident owners were slow to renovate the ballparks themselves and so instead of elegant civic landmarks, fans found deteriorating ballparks that mirrored the conditions of their surrounding neighbourhoods.33

Urban Renewal and the Baseball Landscape

25 The clearest measure of what was happening to the baseball landscape was in the fans' experience. Going to the ballpark was losing its park-like quality, a quality that heightened one's focus on the game itself. At the classic ballparks like old Comiskey, Pastier writes, fans were "immersed in the game as a tactile and psychological event, not just a visual one." The feel of Forbes Field, a fan recalled, "made you concentrate on the game itself." In discussing the design of one of Olmsted's parks, Tony Hiss suggests how the ballparks did this.

26 Olmsted designed Brooklyn's Prospect Park, Hiss writes, as "a physical analogue of the rearranging of one's expectations that occurs whenever one wants to experience an area." Olmsted sought to generate the sense of being "a part of a serene and endless world," "being pulled forward," finding that "everything around them has become more vivid," that one is overwhelmed by "feelings of welcome, of safety, of wonder, of exhilaration." Baseball fans will recognize the device Olmsted used, moving through a dark passage into a green bowl of tight and life. In approaching Prospect Park's Long Meadow the visitor first passes through a dark tunnel called Endale Arch. Hiss describes the "sensory alertness" that comes from die "very pronounced contrast between the gloom of the tunnel.. .and the bright, bright fight and endless view in the meadow." Coming back into the light, the parkgoer experiences a change of perception that "lets us start to see all the things around us at once and yet also look calmly and steadily at each one of them."34

27 Older fans know well a similar experience in recalling their first exhilarating sight, as they passed through the dark passages between the stands, of the green fields of the classic ballparks. Contrast this with architect Philip Bess' description of entering the new Comiskey Park, built on the suburban model. The fan ascends ramps on the exterior of the park "so interminably long, wide, and high that ascending them (to the upper deck, anyway) effectively kills most of the anticipation of arrival, substituting mere relief for the joy that one should feel upon seeing the inside of the stadium."35 The introduction of Astroturf further compromised this experience. Fans' hatred of Astroturf must be understood in the context of what sociologist Tony Hiss calls the need for "gregarious out-of-door recreation." Hiss cites Dr. John H. Falk, ecologist and expert on grass. The grass savannahs of East Africa, Falk explains, was where the human species evolved. Thus grass provides a unique environment "where people from all cultural backgrounds can come together and feel comfortable and relaxed" and reduce the stresses of modern life. Baseball fans, Bess adds, "have sound and healthy instincts when it is appropriate to be part of and when it is appropriate to 'transcend' nature." They doubt Astroturf really improves upon "a well-manicured lawn." The stadia provided an experience of neither park nor city.36

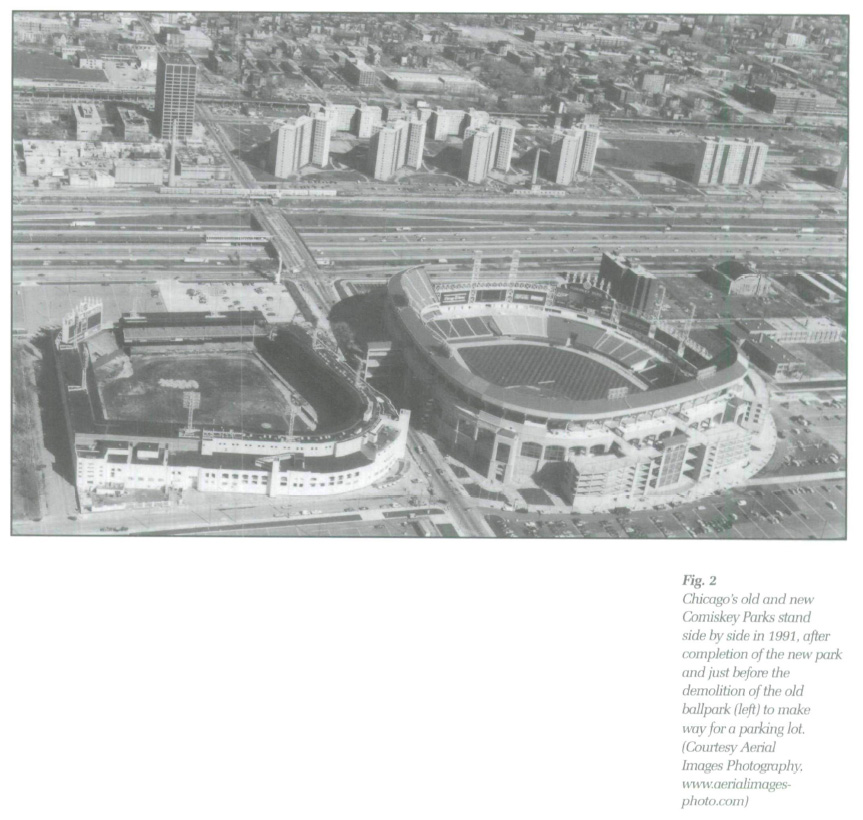

28 Bill James captured the frustration of baseball fans who lamented the loss of the park and city experience when he called the new stadiums "sterile ashtrays." Cincinnati fans who became "bored with the sterile confines of Riverfront Stadium" actually rebuilt Crosley Field on a nearby site. In desperate need of a "personality transplant," Riverfront was a "cold place" compared to Crosley. Crosley was recalled as "a good neighborhood place" because "so many people knew each other. The old park had "that touch... not being nosy, just that friendliness." One fan estimated that he had made hundreds of friends over thirty-seven years of attending games. Reds first baseman Lee May "loved the intimacy and the relationships with the fans near the Reds dugout." Crosley's "smallness enabled it to blend in with the neighbourhood, giving it the blue-collar image that it seemed to adopt." A decidedly urban place, Crosley provided a "sense of adventure."

29 In contrast, Riverfront was "efficiency, harmless, joyfully uninteresting." It appealed to "families more inclined to consuming than adventuring." Riverfront's "concrete sterility" made a trip to the ballpark "more like shopping at a supermarket than dropping in on an old friend." A "model of convenience," Riverfront was the work of the "slickest marketing organization in baseball."37 At the classic ballparks like old Comiskey, the "scents were shellacked onto the walls, adhering to brick like the very soul of the game made manifest; cigar smoke, Old Style beer, sausage, cooking oil." For Riverfront, the Reds management worked with the business school at the University of Denver to devise a spray that would produce an artificial smell to make "everyone happy and hungry."38 Marketing experts searched in vain for a substitute for the park in the city.

30 The interminable stadium ramps that undercut the aesthetic experience of encountering the park in the city remind Pastier of nothing so much as a garage. (Riverfront Stadium actually boasted of being located "in the middle of the world's largest garage.")39 That the new stadia would take on the characteristics of suburbia's most ubiquitous contribution to modem architecture, the garage, is not surprising. The new stadia took on all the characteristics of the suburban exodus that had made urban renewal so insensitive to the needs and the assets of city life. Catering to the automobile, urban renewal projects embraced single-use superblock development, destroying the mixed-use city block and urban fabric that the classic ballparks had respected. The automobile was having its own impact on the classic ballparks as a suburbanizing fan base required the devotion of more and more surface area to parking in ballpark neighbourhoods, contributing to their deterioration.40

31 Good cities need a mix of uses. The juxtaposition of the "monumental and domestic, grand and charming, fragile and resilient, ceremonial and workaday, familiar and strange, shared and personal, cultivated and low," Bess explains, made for an interesting and lively city. A mixture of dwelling, workplaces, retail, and recreation could be particularly enlivened by civic structures and public spaces that gave character and focus to an area. That is exactly what the classic ballparks once provided. But the suburban model rested on zoning and the strict, systematic segregation of functions. This incidentally necessitated driving to each separate activity — hence the suburban stadium and its acres of parking and garages.41

32 The suburban superblock had an immediate and identifiable impact on the baseball landscape and the game itself. From the use of superblocks instead of an existing pattern of streets and blocks came the much lamented uniformity of playing fields. Tiger Stadium, cramped by Trumball Avenue, projected its right field upper deck ten feet over the lower deck, placing it 315 feet from home plate. For fifty years the upper deck in right field served as "midwife for hundreds of little fly balls that turn into strapping homers." Fenway Park's celebrated Green Monster is similarly the result of Landsdowne Street (now Ted Williams Way) just beyond the left field wall. Ebbets Field's inviting and asymmetrical right field fence and the Polo Grounds' short foul lines and sprawling centre field reflected the local streetscapes.42 In the symmetrical, cookie-cutter stadiums, even the ballplayers complained that they could not tell what city they were in from the field. The sprawling superblock sites also encouraged huge seating capacities and the distant upper decks, set above and behind the field level seats — an impossibility in classic ballparks hemmed in by the existing streetscape. The expanding seating capacity then made necessary the extensive parking lots that insured isolation from other city activities and gave the stadiums their sterile quality.43

33 The frustration of baseball fans with the suburban stadium has become widespread. Popular dissatisfaction is generally expressed in terms of the aesthetics of baseball and, increasingly, in terms of the economics of public financing. But the more fundamental and overriding objection should be on urban design grounds — the other problems having derived from poor urban design. To reduce costs and enhance benefits, facility planning must focus on promoting ancillary development. The suburban model is clearly not conducive to such development — but other designs could be. What is necessary is a mix of uses, commercial, residential, event-oriented — to generate the pedestrian traffic that is essential to ancillary development.

34 The key, one careful study explains, is "to counterbalance the tendency of suburbanites to leave the stadium neighborhood for home immediately after the game." Surrounded by a parking lot, a baseball field can accomplish none of this.44 What is needed is the same sensitivity to site that made for the idiosyncracies and the intimacies of the classic ballparks. The classic ballparks, Pastier writes, "were good citizens, economical of land, and gentle to their neighborhoods." They exemplified the virtues of what Jane Jacobs called gradual development, whereas the stadia represented what Jacobs derided as cataclysmic development. The classic ballparks "were rarely perfect and finished," Pastier adds, "more often, they were products of remodeling and accretion" like the best parts of the cities they adorned. These principles of good urban design cannot be taken for granted, not even among professionals. But, happily, baseball fans are gaining a knowledge of urban design principles through their interest in baseball fields. Applying these principles to the baseball field can make them more widely understood and encourage their application to the entire city. Toward that end, Bess and the Society for American Baseball Research's Ballpark Committee designed a model ballpark to replace old Comiskey Park.45

35 Bess designed Armour Field as a traditional urban ballpark, sensitive to its site and the surrounding urban fabric in Chicago. Using a realistic budget and the available site, Bess's plan nestled Armour Field in the rectangle of the neighbourhood's Armour Square Park. To replace that open space, the plan transformed old Comiskey's playing field into a neighbourhood baseball park. Armour's rectangular site would produce the major leagues' shortest foul lines (requiring a relaxation of a minimum distance requirement) and deepest power allies. In turn, the short foul lines, small foul areas, and interior columns for an upper deck cantilevered forty feet over the lower deck would bring fans close to the action. (Old Comiskey's 2 000 column-obstructed seats would be reduced to 150.) The rectangular site also produced two pyramidal bleachers, similar to Wrigley Field's, rising up from the power allies.

36 Drawing on Chicago's factory vernacular, the brick and concrete exterior of the ballpark blended with an active, tightly-knit neighbourhood. Six-story mixed-use buildings would surround the park. Providing commercial space on the first floor, offices on the second, and residences above, these buildings would promote economic and social activity around the ballpark. Residents of the neighbourhood would be able to see into the park and fans inside would be treated to a spectacular view of Chicago's Loop and Gold Coast skylines. Instead of blighting the site with surface parking, Bess placed multi-story garages along the railroad tracks to the west and an expressway to the east. Recognizing that inadequate parking would encourage a blighting of the area with surface lots, Bess added his most innovative feature: a network of four miles of boulevards within a square mile of the park. On game days, these boulevards would provide five to six thousand parking spaces within a ten-minute walk. At other times, they would serve as a neighbourhood park. Bess's design would heal and enhance a neighbourhood rather than destroy it. Baseball fans who examine this design will be torn between tears of joy, that someone else understands and cares, and tears of frustration, that the White Sox and the public authorities resolutely ignored Bess's design.46

"Retro" as Theme Park

37 Bess's design, or rather the widespread dissatisfaction with the suburban stadium of which it was an expression, has had some impact. We are now in a period of baseball field construction that is outpacing the two earlier bursts of construction of the classic ballparks and the suburban stadia. The best of the new parks pride themselves on the "retro" look, honouring the classic ballparks. But too often the plan appears to be to devise marketing ploys to exploit commercially and superficially the fans' growing understanding of the baseball park's historical and civic roots. The White Sox made few concessions to the "retro" mood, not even replicating old Comiskey's distinctive embedded-brick "C's" on the exterior walls. But even the White Sox encouraged their fans to come out and see the beloved relic of old Comiskey — even as they abandoned routine maintenance.

38 The park that replaced old Comiskey is hardly a traditional urban ballpark. In what Bess calls the "commodification of the old Comiskey Park's 'character'," the White Sox provided the new Comiskey with a version of the beloved picnic grounds behind old Comiskey's outfield fence. What was once afirst-come,first-servedlocation with tables and the option to bring food from the concessions during the game, became a payand reserve-in-advance $20 all-you-can-eat buffet open only the two hours before the game. The White Sox's advertising hype promised the "intimacy, charm, and character" of the old ballparks. But both the larger foul territory and the service road between the outfield fence and outfield bleacher placed fans — even in the first deck — further from the field than at old Comiskey. The front row of new Comiskey's upper deck is actually further from the field than the last row of old Comiskey's upper deck.47

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 239 The White Sox's claim that new Comiskey was an urban ballpark in tune with the architecture of older American neighbourhoods is the most egregious. Where the old ballparks "adjusted themselves to, and had their playing fields and character shaped by, the city in which they were located," Bess reports, the new Comiskey forced the city "to do all the adjusting; it is essentially anti-urban and does not accommodate city life." Built upon a superblock that obliterated the existing streetscape, the new Comiskey's expansive parking lots precluded a surrounding neighbourhood of bars, restaurants, and shops. Not only did the new Comiskey's design insure that no multiplier effect would create the jobs and tax revenues to partially repay public subsidy. Rather than repair and enhance a neighbourhood, the new Comiskey supplanted it with what Pastier calls "a 7,136 car sea of asphalt." The mall-like concourse of shops inside the stadium is no substitute for lively city streets outside. No "pre- or post-game food and drink will be found, or allowed," Bess writes, "within nearly a half mile of the park."

40 Such opportunities appeared to the White Sox as merely a matter of undercutting the ballpark's concession revenues — all of which went to the team, none to the city. The South Armour Square neighbourhood, including 220 low-income, black households, was simply leveled. The remaining church-sponsored housing for the elderly and handicapped is segregated by chain link fences, though the residents are treated to post-game fireworks launched 100 feet from their dwellings. Fully-enclosed, lacking any view of the city (though fans in the upper deck are treated to the drone of the Dan Ryan expressway), the new Comiskey is "the perfect modern ballpark: no interaction at all with the surrounding neighborhood; no relation to the city; no view of anything." Even the architectural details on the outside facade are obscured by pedestrian ramps carrying suburbanites directly from their cars to the game without setting foot in South Side Chicago.48

41 The disappointment with the new Comiskey was much in the air as the Baltimore Orioles began planning their new facility. "Everybody knows they like the older facilities," Janet Marie Smith, Orioles vice-president in charge of the project explained, "but people aren't able to quantify what it is exactly they like about them." Smith discovered a few simple design principles in the classic ballparks. "The buildings were always very civic in appearance," she noted. "They could easily have been a library or a city hall." They employed park-like colours, usually green. Where allowed, advertising was integrated into the architecture, worked into the scoreboard or outfield wall. The advertising was local as well, instead of the ubiquitous national brands of today that "simply reinforce our loss of place, and thus of self." Idiosyncracies, like Crosley's inclined terrace in left field (the product of dealing with marshy ground), gave each park a personality. The ballparks employed "traditional street walls that came right up to the sidewalk." Inside, the traditional street walls supported grandstands that brought fans close to the field, a quality enhanced with small foul areas. Outside, these walls were low and contained within the building profile. As a result, Smith concluded, "baseball rubbed up against commerce and life."49

42 The Orioles management battled with the Maryland Stadium Authority, whose interest was rninimal cost, and with HOK, a construction firm masquerading as designers, to build a Camden Yards "mindful of the past." But many wondered if the "history" at Camden Yards would be as "slick and glib" as Baltimore's Harborplace theme park, where "tradition" was placed at the service of "your basic upmarket shopping mall." The "retro" parks do have that quality, as they offer an expensive and inadequate simulation of a baseball park in the city. Like the theme parks that cynically commercialize a genuine desire for city life, the "retro" parks are so expensive that they cannot replicate the city's essential quality, the promiscuous mixing of people.

43 Smith was more accurate in her nostalgic take on the classic ballparks than she knew. Fitting the park to the existing streetscape, she argued, meant "the game is taking on the character of the community it is in."50 The "rétros" do indeed reflect something of their surrounding communities, namely the social inequality of contemporary America. These are simply not places designed for the average fan. Even at much-lauded Jacobs Field in Cleveland, which opened in 1994, private concourses and restaurants and other plush amenities separate the average fan from those in the premium seats. "Overhead walkways that elevated the well-to-do above the masses," one architect noted, made "social stratification all too clear."51 But no place captures this like the new Comiskey where the rich are comfortably ensconced near the action, attended by waiters, while the rest of us cling to the steeply-inclined upper deck watching the action through binoculars. The thirty-five percent rake of the new Comiskey's upper deck is so frighteningly steep that it even "makes one think twice about jumping up and cheering for the home team."52 The "rétros" are a more appropriate metaphor for elite and populist America than we might like to admit.

44 Postmodern has been the adjective of choice in criticizing the "rétros." With "postmodern packaging," Pastier argues, the "rétros" resemble "a semi-upscale mall" far more than an urban ballpark. Ballpark architects too often "interpret charm and character as facets solely of facade design." Rather than respond to site and history, Pastier concludes, they engage in "an arbitrary, generalized postmodern exercise." The substitution of city experience and tradition with commercial, simulated substitutes is the quintessential postmodern exercise. Theme parks and shopping malls, the postmodernists warn, are supplanting our memories of what city life is like. (The "ballpark comes equipped with memories," Sports Illustrated oddly enthuses over Camden Yards, as is appropriate to "a provincial, blue-collar, crab-cakes-and-beer town with thick roots.")

45 As theme parks, the rétros peddle urban and historical experience to a citizenry eager for it, but they have the look and feel of affluent suburbs. Comfort and spaciousness, in parking, concessions and seating, are the design imperatives. The design that inspired the new Comiskey Park and other new parks is the shopping mall. The concourse that encircles the last row of field-level seats at Comiskey has reminded every reviewer of a shopping mall. A Michigan official charged with overseeing a new park for the Tigers cited his model as a suburban Detroit shopping mall. Pastier calls the new parks "sprawling objects of variable urban sensitivity," sitting "like shopping malls, in seas of open parking."53 Theme parks and shopping malls, even in our ballparks, threaten to take the place of city streets and enshrine the commercial transaction as the only authentic city experience.

46 Camden Yards was, however, the best of the rétros, the one most integrated into its site and city, mindful and respectful of history. The rétros to follow seemed not to recognize its virtues. In Denver, all vernacular industrial structures adjoining the new ballpark were destroyed. In Cleveland a functioning public market was shut down rather than weaved into the design. Landscape architects are commonly involved. "Our charge," one who worked on Jacobs Field explained, "was not only to coordinate die overall design, but to be the watchdog for public spaces." Yet the watchdog did not prevent the demolition of surrounding buildings for parking lots or prevent the sharp segregation between ordinary fans and occupants of luxury seating.54

47 At Coors Field in Denver, a design team that included landscape architects "made an effort to cover all the bases in creating a sense of place." Conceived as part of a thirteen-block district, rather than a four-block building site, their design included a $370 000 public art initiative. Yet one landscape architect warned of a "real concern that building owners will tear down old warehouses for parking." Although Coors creates several inviting public spaces, its decaying but historic north and east edges lack protective zoning or historic district status. Nor do the Coors architect believe the ballpark can "revive neighborhoods in the Jane Jacobs sense. Working-class ventures have long ago left Lower Downtown. Rather, Coors should be judged as die centerpiece of a so-called urban entertainment district."55

48 Strangest of all the new parks, The Ballpark at Arlington, Texas, placed an eclectic ensemble of postmodern simulations of an urban ballpark in the middle of an undeveloped, suburban lot. Its immediate context is "Six Flags Over Texas, Wet 'n Wild water park." Thus The Ballpark at Arlington stands at "the epicenter of the newer American landscape of freeways and strip shopping centers and amber waves of satellite dishes." It has justly been called a "hollow hotel," a self-contained baseball theme park with no connection to any real urban community. Maybe to distract attention from a backdrop of oil rigs and amusement park water slides, the Ballpark's "brick towers and soaring arches evok[e] everything from the campanile at St Mark's to the Ponte Vecchio." The effort was to turn "no place into someplace," but it is not yet clear whether it has "created a different kind of suburban place or just another destination." The Arlington facility has at least addressed one problem of suburban stadiums, the acres of asphalt — here turned into "smaller landscaped 'rooms' for 50 to 200 cars."56

49 All the postmodern styling and packaging obscure, of course, that the architectural designs aim at maximizing club revenue. An architect for Osborne Engineering Company, long-time designer of ballparks, explained that retro "designs seek to revive the classical style while incorporating modern needs — luxury boxes, wider seating and unobstructed sight lines." The problem is that the two are not compatible. "Why shouldn't thousands of fans in the upper deck rejoice in an intimate view," the architect asks, "Just because several hundred would be blocked by pillars?"57

50 The answer, he surely knows, is that the driving force for architectural design is to make money for the teams. To insure that field-level seats command the highest possible price, teams insist that there be no column-obscured seats. The upper deck has to be placed not directly above the first level supported by columns, but above and behind the field level at a steeply ascending angle. To make matters worse, skyboxes, club seating, private restaurants add additional levels between the field and the upper deck. New Comiskey's upper deck, Bess writes, "has the character of an entirely different, and notably inferior, stadium."58 Similarly, doling out space for parking, concessions, luxury seating, and ease of circulation, club revenue is the guiding light. Nothing else gets in the way.

The Cash Value of Civic Consciousness

51 While schools, transit and other public facilities are starved for funds as tax revenues dwindle, legislators and owners plot schemes for new tax levies to build stadia to replace other publicly-built stadia less than forty years old. Twelve new parks have been built since 1989, each of them costing a minimum of $200 million, with more on the way. This is despite fan opposition and bitter second thoughts.

52 "We now know," Chicago Tribune columnist John McCarron explains, "though certain suits will never admit it, that old Comiskey should have been saved and rehabbed; that the old neighborhood around it should have been renewed, not removed." In Boston, the Red Sox now insist that Fenway Park must give way to a "retro" park. TV ads explain that in the new park, seats will be arranged so that fans were "just as close to the action, but not to your fellow fan." But as the new Comiskey showed, accommodations for corporate clients mean more distant seats for the average fan, seats at higher prices on top of the tax bite public subsidies take. Boston's Mayor Tom Meinin, having signed on to the campaign for a "retro" Fenway, explained that it would help save a "blighted" neighbourhood. Challenged on that description of the lively Fenway neighbourhood, the Mayor added: "We don't mean 'blight' in the real sense of the word 'blight'."59 What could be so important to cities to put up with this kind of abuse?

53 The dynamics of the vote on Cleveland's Jacobs Field suggests one answer. Suburbanites voted for the public subsidy for Jacobs Field, but inner-city voters, disproportionally burdened by the taxes on tobacco and liquor that financed the park and dependent on the funds-starved public schools, opposed the project.60 Perhaps baseball facilities do nothing for cities and their citizens, but are merely entertainment zones for suburbanites. Advocates of public financing argue that subsidies generate a multiplier effect that provides jobs and tax revenues within the city. But studies have shown again and again that this impact is grossly exaggerated. Local spending is simply redistributed while the jobs provided are generally low-paying and seasonal.

54 Ancillary development, while possible if planned for, is certainly not automatic and impossible in suburban-style stadia surrounded by parking lots. Yet every facility built since Dodger Stadium in 1962 has benefited from public subsidy and the trend continues. Although cities are demanding private partners more and voters are approving tax levies less, public subsidies remain significant — in acquiring land below market rates, providing infrastructure, relocation expenses, and tax abatements. Why do cities continue to subsidize baseball? The most thorough studies show that a new baseball facility provides "intangible, non-economic benefits to municipalities," namely the "psychic satisfactions attendant to being a 'major league' city, the stadium as local landmark, etc." In other words, ballparks promote civic consciousness, civic pride, and a sense of place.61 These are indeed important and valuable things. But exactly how much and in what form are cities paying for this?

55 Consider the White Sox's deal, which is hopefully as bad as it gets. Illinois Sports Facilities Authority, chartered in 1986, issued $150 million in bonds to be retired in twenty years at a cost of $260 million. Stadium-generated revenues have paid for none of this. Instead a two percent tax on hotel rooms and direct city and state subsidies will retire the bonds. Stadium revenues are shared on the basis of attendance — if the White Sox sold every ticket for every game, the ISFA would get $4.3 million (about a third of annual debt servicing). But if the White Sox drew substantially below 1.5 million fans the ISFA could actually wind up paying the White Sox as much as $2.5 million. Revenues from concessions, parking, and skyboxes all go the White Sox. Capital repairs on the park remain the responsibility of the ISFA with routine maintenance the club's responsibility. But even routine maintenance is subsidized with $2 million in public money regardless of what the White Sox actually spend. The ISFA also absolved the White Sox of all property taxes.

56 Cheaper proposals to renovate Comiskey Park, to rebuild it, or build the new park on a site just north of the existing park were all rejected by ISFA for the alternative, which required multi-million dollar relocation expenses of residents and municipal facilities. In the process the ISFA destroyed — as a suit on behalf of the neighbourhood put it — "a stable community, South Armour Square, composed almost exclusively of Black residents, by expelling both the existing residents and important light industry...[and] by isolating the remaining residents... from surrounding communities, stores, and recreational and other neighborhood benefits."62 Whatever civic pride or sense of place Chicago might derive from the new Comiskey is undone by the misuse of public funds and the destruction of a stable neighbourhood.

57 The White Sox were able to extort public money for a new stadium because Governor Thompson, and Mayor Washington before him, calculated that the city would experience a devastating psychological loss — if not financial — if the White Sox left. At stake was not simply an economic asset, but civic pride and generations of memories associated with the White Sox. The question of baseball parks is an important one and may have a significant impact on the future of our cities. But the costs have been too high and the payoffs too low. These massive, voluminous structures are not cheap. They can only be built because the attendant social and economic costs have been borne by states and municipalities, while baseball fans bear the aesthetic costs. The new ballparks, Pastier writes, "are public buildings in the fiscal sense," but a lack of "concern for the ordinary fan, urban context, civic space, and pedestrian use" rob them of any general public benefit.63

58 The public and civic interest is simply not part of the process. As one stadium architect put it, "I'm a dinky little stadium architect. I'm not trying to design cities."64 Instead stadiums are the "perfect vehicles for city hall insiders to wheel and deal," providing "a ribbon-cutting to the for," lots of consulting and construction contracts to let, and choice seats for popular events to distribute. The costs are borne by "working stiffs who consider themselves lucky to sneak the family into the bleacher seats once a season." The benefits go to millionaire owners, public officials, and those in the luxury suites who "sip sauvignon blanc."65 Meanwhile the stadia teach the young that, at best, public life is a matter of long lines, large cash outlays, and high prices for poor quality.

59 The future is not promising. Consider Cincinnati's proposed "Great American Ballpark," which is to be built with $300 million in taxpayer money and is still in the planning phase. When design plans were withheld from public scrutiny, the City Council angrily asked "why the public isn't allowed to see what it's paying for." There was "no public scrutiny of a massive public project," one councilman fumed, "We're already seeing decisions being made for the wrong reason." Stadium planners had given "conditional approval to shutting the public out of public space." The mayor insisted that the "public has an absolute right to know what is going on with that stadium." A member of the Urban Design Review board, ostensibly charged with insuring the design advanced the city's goals, helpfully reminded the mayor that the relevant documents belonged to the Reds and their architects. The review board pontificated: "We don't make anything public."

60 But the board did have its own concerns, objecting that the design provided only a "modest public area of the plaza that does not fulfill the civic promise of the project." Objecting to the "privatization of public space," local architects complained that the plaza had been "designed with economics in mind — simply to 'catch the crowd' and draw them into a concession row" that would generate additional revenues for the team. When finally revealed, the design appeared to create "a field that is so uninspired it is almost somnambulant." Some feared a blight of "blue-blood flaunting," that is, the placement of luxury suites at the best locations for viewing the game. It still is not clear if the Reds will go ahead with plans to wall off part of the concourse level from the field to capture the fans' interest (and money). In any case, a wide, mall-like concourse remains a major element in the design.66

Repossess the National Pastime!

61 The construction of sports facilities thus reflect how much we have lost control of our governments to corporate interests. There is a "spiraling corporate bidding war between different communities over teams," the Washington Monthly reports. Public officials, Consumers'Research explains, "have ignored or failed to realize just how few jobs professional sports teams produce" and how little they impact location decisions of major firms. "There has not been an independent study by an economist over the last thirty years that suggests you can anticipate a positive economic impact." Ballpark revenue goes to owners and players. Once one removes the myth of the ballpark as economic engine, one sees that localities are simply "taking public funds to guarantee profitability to a private business."

62 Free agency has so escalated players' salaries that they can be paid — and profits maintained — only if public subsidies for income-generating parks can be found. These are found all too easily from officials who did not bother "to ask whether cities could prosper from professional sports." Even Camden Yards, two Johns Hopkins economists estimate, reduced private Maryland incomes by $11 million. The bidding war is encouraged by — among other things — a federal tax exemption on the local bond issues that finance new sports facilities. Federal tax breaks often make possible the other inducements that state and municipal governments use to entice teams away from their current communities. All these are forms of corporate welfare that have generated strange bedfellows; both The Wall Street Journal and The Nation denounce the practice. Meanwhile cities are starved for tax dollars.67

63 Sports fans are notoriously difficult to organize — even Ralph Nader failed — and teams are adept at courting legislators with free tickets and personal contact with star players. But it is not for a lack of an interested public that the destruction and boondoggling goes on. Passionate fans ring old ballparks slated for replacement and pledge to maintain the vigil. Fans united as "Save Our Sox" sought to make old Comiskey a national urban park on the model of the Lowell, Massachusetts, textile mills. Instead of a theme park, Save Our Sox wanted a park with its original purpose intact and supplemented by historical perspective and education. It was found eligible by the National Park Service, but the White Sox vetoed the plan.68 The Tiger Stadium Fan Club developed their own Cochran Plan to preserve the old park. But the Tigers ignored it, even as fans in Tiger Stadium unfurled banners reading "If you build it, we won't come."69

64 Many voices have called for referenda on stadium deals and such referenda did block public subsidy in San Francisco. President Clinton lectured owners in 1999 to consider "the obligations owed to the people in your communities. Make investments in your community second only to your priorities to bring home the championship trophy." But even Clinton failed to challenge the formal and informal prohibitions that preclude public ownership of sports franchises. Ballparks can be civic assets (they often are in the minor leagues, where public ownership is common and players' salaries are pathetically low). But it does not happen automatically.

65 Perhaps the greatest irony is that the best of the recent ballparks is the one that returned to "old-fashioned capitalist financing." Although taxpayers contributed $15 million and assorted infrastructural improvements, San Francisco's Pac Bell Park arose on a foundation of $300 million in private funds. (This was after San Francisco voters rejected publicly financed parks four times.) The lack of public subsidy ironically explains part of Pac Bell's success as a civic project. Rather than taking the prime downtown real estate that publicly-financed parks take, Pac Bell chose to build in the same sort of gritty, working-class neighbourhood in which the classic ballparks arose. (The Pac Bell site is in a rapidly gentrifying area with a bayside view.)

66 The site is well-served by public transit and the design treats the site "deferentially," providing a public promenade along the bayfront. The ticketless can watch part of the game from the promenade, which has generated game-day crowds and new commercial ventures. The tightness of the site is made a virtue with a quirkily close right field foul line (307 feet (94 metres) from home plate) that rapidly expands to 420 feet (128 metres) in right centre, allowing home runs to drop into the bay down the line and triples and inside-the-park-homers to rattle around in right-centre. It is not perfect — the eighty-foot (24-metre) long Coke bottle above the left field stands announces the centrality of the concession dollar while the expansive concession areas and premium seats push upper-deck fans far from the action. The range of activities promoted within the park also seem to de-emphasize the game itself. But Pac Bell does suggest what might be done even without public subsidies.70

67 At the very least a true partnership is needed. Without making owners part of an urban development partnership with investment in the ballpark neighbourhoods, as was done in Phoenix's new Bank One Ballpark, team owners have no stake at all in the community and are just a sweetheart deal away from bolting.71 Jay Weiner's Stadium Games shows how in Minneapolis owners and civic leaders have manipulated civic pride to exploit taxpayers for the benefit of a privileged minority. Local lawyer Hugh Barber, whom Weiner calls "the unsung hero of stadium history," repeatedly demanded stadium planning for the public good first and foremost. Barber argues that professional sports need the Minneapolis-St Paul market more than the Twin Cities need professional sports. (This is, incidentally, an insight with broader implications for American citizens confronting the multi-national corporations of the global economy.) Minnesotans, who have refused to build a park to subsidize the billionaire owner of the Twins, appeared to have learned the lesson. Taxpayers are daring to ask what the city will get from building a new stadium.

68 Like the citizens of the Twin Cities, other communities should demand a percentage of tickets sold at affordable prices, living wages for employees, public disclosure of team finances, and a portion of profits for local youth sports. There must be an additional set of stadium uses, from art galleries to police stations, to make the ballparks a civic asset on other than game days.72 Pac Bell suggests such improvements are possible even with private ownership. But a more direct and forthright appeal to civic pride and public initiative is more promising.

69 Repairing the urban fabric, increasing tax revenues, and enhancing civic consciousness are all central tasks for American cities in which baseball parks can assist. Indeed the future of cities in competition with one another depends upon the distinctiveness of their central neighbourhoods, not on the homogeneous suburban fringes that are virtually identical in every metropolis. But the current approach to constructing baseball parks is all wrong. What the classic ballparks offer us more than anything else is a glimpse of the city's possibilities.

70 The civic aspirations of those classic ballparks were contagious. In 1923, the year Yankee Stadium opened, a New York reporter interviewed Yankee owner Colonel Huston on "Baseball's Future." Baseball, the reporter began, "is practically a monopoly, and a monopoly whose support must come from the public." Then he posed the "fundamental" question. "Why cannot the chief municipalities interested take over baseball and manage it themselves?" The Colonel balked. "Why not?" the reporter continued. "We have municipal ownership of art galleries, of public parks, in some cities of choral societies. Surely none of these appeal more to either civic pride or pleasure than baseball?" Huston dismissed the idea as unworkable, but earlier in the interview he had argued that baseball "lives only because of the public."73 Huston was right about that. It is time to repossess the national pastime.

71 What is it that the owners actually "own" anyway? The public already owns most of the parks. Do owners own a game the American people created out of their hopes and dreams, values and skills? Those millions of us who talk and write about the game, embellishing its past and present and imagining its future, create new generations of fans and strengthen the games' place in our culture. Can the owners say as much? Do the owners own the players? Certainly not any more, although at tax time the owners do depreciate these "assets" to avoid paying their fair share. Mothers and fathers, coaches and fellow (if less talented) players, the admiring and encouraging fans, they created the players. In short, baseball is a socially-created form of wealth. The only thing the owners actually own is a franchise to sell to us, at monopoly prices, the national pastime that we have created.

72 Why are those franchises worth in excess of 100 million dollars? Because we have given the owners a monopoly (thanks to the 1922 antitrust exemption). We allow them to be the only game in town and then they blackmail us into building them bad stadia with public monies. We have been willing to allow the owners to get rich off of our game as long as they took reasonable care of it. But owners who, as Bess puts it, "appear to love money more than they love the game risk alienating the affections of the fans."74 Eight work stoppages since 1972, not a single negotiated contract without one, is quite enough. Another work stoppage now, incredibly, looms. Added to this, the destruction of shrines and the erection of theme parks is too much. The owners have blown it. It is time to take the game away from them.

73 It is the fans who will have to do it. We might try, as did a group of New York Yankee fans, to purchase one of those multi-million dollar franchises. But we do not need to do that. Instead we should demand that Congress end the anti-trust exemption and then watch those franchise values collapse as new investors flock to the industry. Those long-blackmailed cities could be among the first to benefit, fielding their own teams as already happens in the minors. Although the owners have long blocked municipal ownership in the majors, its time has come.

74 A lot would have to change. But we must recognize that the classic ballparks are so beloved because they speak to the possibilities of city life. They call to us an earlier time before we gave up on cities, when we aspired to build what settlement house reformer Robert Woods called "a broadly and humanly serviceable city, powerful, generous, considerate." Henry George showed how it might be done. Socially-created forms of wealth, George insisted, must not go "to the enrichment of individuals and corporations" but to "the improvement and beautifying of the city." Our cities might be filled with playgrounds and gardens, libraries and theatres, lecture halls and ball parks, George argued, and "in a thousand ways the public revenues made to foster efforts for the public benefit."75 A municipally-owned and -operated baseball league, boasting the best ballparks and richest city life, might recapture some of those lost possibilities. Uniting Olmsted's call for judicious public investments in parks and green, open spaces with George's desire to capture socially-created wealth for public purposes, we might yet civilize America's cities.

* The term "baseball field" will be used as a generic category that includes two distinctive forms, the urban ballpark and the suburban stadium.

* By "baseball landscapes," I mean to call attention not only to these large public structures but their physical settings and relation to the surrounding city.