Articles

Sifting Through the Papers of the Past:

Using Archival Documents for Costume Research in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Quebec

Abstract

Quebec archival documents are a rich source for costume and textile descriptions particularly for the era of the French regime, a period for which we have no extant artifacts from which to draw costume evidence. Moreover, little costume history is available in English for this important chapter in Canada's history. In this paper, the author examines the French probate documents known as inventaires des biens, contrats de mariages, and testaments as potentially rich sources for research in Canadian costume history. Each type of document is discussed in terms of its importance and use in the lives of the early colonists, then analysed for its textile and clothing content. Examples are drawn from seventeenth and eighteenth century documents for those living in the town of Quebec from 1635 to 1760. Most of the garments are no longer known by their seventeenth and eighteenth century terms and many have disappeared from use altogether. Textiles have met the same fate and while some of the terms like taffeta remain today, their fibre content is quite different. As a result, a glossary of terms has been provided for both garments and textiles.

Résumé

Les documents d'archives du Québec offrent de précieuses descriptions des costumes et des tissus d'époque, en particulier sous le régime français, période pour laquelle nous n'avons aucun vêtement d'origine qui nous permettrait d'obtenir des preuves des costumes. De plus, nous ne possédons que très peu de documents en anglais sur l'histoire vestimentaire de cet important chapitre de l'histoire du Canada.

Dans cet article, l'auteur examine les documents homologués (en français) - des inventaires des biens, des contrats de mariage et des testaments - en tant que riches sources potentielles pour la recherche sur l'histoire des costumes au Canada. Chaque type de document est abordé selon son importance et son utilisation dans la vie des premiers colons, puis on fait une analyse du contenu relatif aux tissus et aux vêtements. Des exemples sont tirés de documents de l'époque à propos des habitants de la ville de Québec entre 1635 et 1760.

La plupart des vêtements ne portent plus le même nom qu'aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, et un grand nombre de ces termes ne sont plus en usage aujourd'hui. Les tissus ont subi le même sort et, bien que certains termes comme taffetas soient encore employés de nos jours, leur teneur en fibres est passablement différente. Par conséquent, un glossaire des termes relatifs aux vêtements et aux tissus est annexé.

1 When Françoise Lemaître de Lamorille died in 1724, an inventaire des biens—an inventory of all goods in the home and boutique—was made. Among other things, an extraordinary and expensive wardrobe emerged, a wardrobe that reflected her status as wife of successful merchant Charles Guillimin.1 A few years earlier in 1718, the inventory of Charles de Monseignat shows a less sumptuous wardrobe, but one no less in keeping with his status as contrôleur de la marine et receveur du Domaine.2

2 Archival documents such as the inventaire des biens have been used by French-Canadian historians as a source of historical costume and textile information for many decades. Not surprisingly, these documents have been used less by Canada's Anglophones. But for anyone interested in the costume and textile history of early Canada the rewards can be gratifying. Importantly, the use of archival documents for early Canadian costume history research demonstrates the possibilities that exist for retrieving a history of clothing and textiles where no extant examples exist.

3 This paper is drawn from research conducted for a Master's thesis that used 118 archival documents to provide documentation of clothing and textiles in the town of Quebec during the French regime.3 It supplements previous work by American costume historians Pat Trautman and Donna Bartsch on the use of probate documents for American costume history research by providing a Canadian aspect to the use of archival documents for costume research in Canada.4

4 While these archival documents can reveal a wealth of information for researchers, that information is not always easy to retrieve. In addition to lack of expected accents, inconsistent spellings of the same word, and spellings that do not conform to contemporary versions, the researcher is confronted with the problem of deciphering the handwriting of the notary.5 Seventeenth-century French writing is somewhat gothic in nature and difficult to read. While eighteenth-century script is more like our own there were numerous notaries who had wicked writing styles.

5 The focus of this research is on the first permanent settlement in New France, the town of Quebec, founded in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain. One can only imagine the difficulties involved in survival in the early decades: hostile Amerindians, life-threatening diseases, bone-chilling winters with mountains of snow, one supply ship each year. Thus, it is not surprising that there are few documents for the very early years in which one might find clothing and textile references. The oldest archival document found to reveal historic costume information bears the date 1635: it is a testament, coincidentally that of Champlain. Hence, this paper will explore documents from 1635 to 1760.

6 Two key documents provide costume and textile information: the inventaire des biens and the contrat de manage. A third document, the testament, is less useful for clothing and textile researchers but should not be excluded as an occasional gem of information will surface from within it.6

7 As previously noted, French-Canadian historians have used these documents in varying degrees for decades. In examining clothing and textiles during the French regime, Robert-Louis Séguin, Bernard Audet, Luce Vermette, and Monique La Grenade have focused on colonists in the Montreal area, île d'Orléans, Trois-Rivières and Louisbourg respectively.7 But not all of their studies are available in English. While Vermette's work at the forges of Trois-Rivières has been translated into English it contains the least amount of clothing and textile information of the four mentioned. La Grenade's study of masculine costume at Louisbourg is significantly more useful and while it has been translated into English her similar work on feminine costume and children's wear has not. The unparalleled work of Séguin remains in French as does that of Audet.

Inventaires des biens

8 The inventaires des biens is the French colonial document that reveals the greatest amount of clothing and textile information, and for good reason: after the death of a person, the civil law known as Coutume de Paris required a full accounting of material goods for all those having heirs.8 The inventory was made to record the goods of a succession, or in the case of a married couple, a joint estate of goods.

9 Under the Coutume the division of a legacy was predetermined and the counting of each article of goods, furniture, titles, and papers facilitated the division of the legacy. Thus, moveable assets are one element faithfully recorded.

10 To their credit, notaries followed a consistent pattern when recording assets by moving systematically from room to room. This results in the reader being able to paint his/her own image of the surroundings as the notary, attending officials, and family of the deceased moved about the premises. In general, kitchen items were listed first, followed by the parlour, which might also serve as a bedroom.9 Major items would be noted before examining the contents of armoires and coffres of varying sizes.10 Once the house contents had been inventoried, the attending officials would move outdoors to count each animal and itemize tools and equipment. The last items recorded were the papers that covered the couple's marriage contract, sale of land, etc., along with the debts owed to the deceased, and those owed by him/her.11 Thus, when examining the inventory, its structure alone is helpful in locating sections of the document where clothing and textiles are expected to be seen. If the deceased had been a merchant, there may have been a boutique at the site. Here, the appraisers would take great pains to itemize all the textiles, even small scraps of fabric, along with buttons, buckles, and necessities like shoes and stockings.

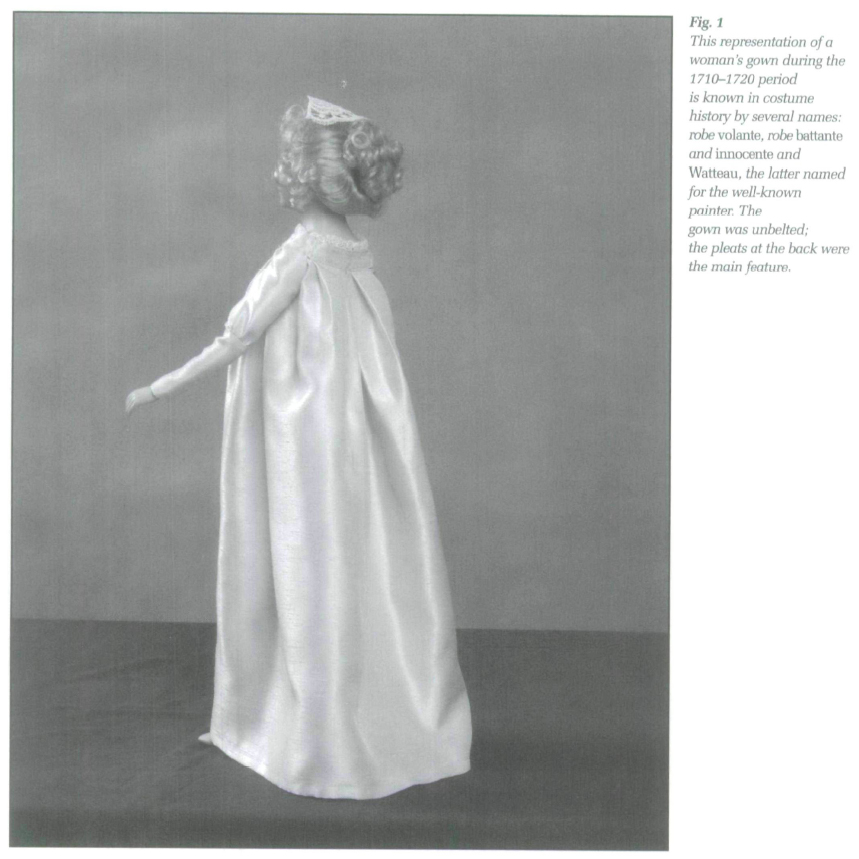

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 Inventories of merchants reveal the greatest amount of information since merchants were generally wealthier than many other colonists, hence they had more moveable assets.12 The clothing owned by these merchants testifies to this. Importantly, the inventory of the boutique allows the clothing and textiles researcher a glimpse of the wide range of goods, colours, quantity, and prices that existed at a particular time. For example, the capot was often made from créseau, ratine, cadis, and pinchina, wool fabrics similar to a serge.13 Looking at the boutique inventory prepared after the 1701 death of Charlotte Françoise Juchereau, we can see that one entry for sixty-seven aunes of cadis was held in stock with a value of 25 sols per aune.14 Since a man's capot required about twelve aunes we can calculate that if the sixty-seven aunes of cadis were used exclusively for making capots, there would be sufficient for at least five capots at a cost of approximately fifteen livres each.15 If we examine the cost of capots in wardrobes of the same period we can see that a completed garment was valued at sixteen livres.16

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 While no ready-made garments were listed in boutiques, the numerous accessories like fashionable stockings and shoes and utilitarian buttons and buckles can be seen. In a few rare instances, the mention of garments that were "used" raises the question of whether such garments belonged to the owner and simply found their way into the boutique by accident or intent or whether a second-hand clothing market existed or may have been developing at that particular time.

13 The inventaire des biens of Françoise Lemaître de Lamorille in 1724 provides an excellent example of both the richness of information to be found in this particular kind of document and in the opulence of the wardrobe of the wife of a successful merchant.17 In the interest of space, the items have been edited:

- 63 chemises

- 3 mantelets

- 1 jupe

- 1 pr pantoufles

- 3 écharpes

- 9 coiffes de nuit

- 4 tabliers

- 3 robes de chambre

- 4 jupes, manteaux, jupons

- 12 pr manchettes

- 8 pr bas

- 4 corsets

- 7 jupons

- 3 jupes and manteaux

- 4 crémones

- 3 coiffes

- 5 pr souliers

14 Such evidence of a wife's finery helped to reinforce the status of the merchant himself. The number of items are impressive as a listing, but when the details of textiles are added, the wardrobe takes on new meaning. Four of her gowns, each consisting of jupe, manteau, and jupon were made of brocaded satin, damask, and taffetas d'Angleterre, with values of 176 livres, 240 livres, 260 livres, and 350 livres.18 Accessories to her wardrobe included silk stockings, embroidered shoes, belts that were silver on silk, a silver belt buckle with diamonds, and silver shoe buckles. In all, her wardrobe totalled 3 762 livres.19

15 Although the occupation or status of Sieur Denys de Vitré could not be confirmed, when his wife Marie Blaise de Bergères died in 1728 her wardrobe indicates that he was no mere labourer. Among her possessions were:

- 3 tabliers

- 2 écharpes

- 6 pr manchettes

- 4 coiffes

- 1 peignoir

- 3 cornettes

- 1 manchon

- 2 manteaux

- 5 pr bas

- 6 dormeuses

- 20 chemises

- 2 éventails

- 1 pr pantoufles

- 2 robes de chambre

- 4 bagnolettes

- 1 jupe

- 5 robes

- 9 colinettes

- 7 jupons

- 3 corsets

- 2 mantelets

- 1 cape

16 Looking more closely at the entry details, we find four pair of the bas were of silk, in black, pearly grey, and pink; a fifth pair in green was decorated with a white fork design. One gown of jonquil serge was lined with a toile designed with squares while another robe of jonquil taffeta came with a jupon trimmed with silver lace. In addition to the completed garments, there was a quantity of fringe that was destined for the bottom of an old jupon.20 While this particular inventory does not attach values to the items recorded, the number of garments and types of textiles found in the document indicate that the couple were financially comfortable.

17 Inventories for those colonists who enjoyed a more comfortable way of life are frequently the documents with the most costume information. But documents for those colonists of lesser means are valuable for drawing comparisons and providing a more complete view of the costume of early colonists. Guillaume Hébert, for example, died in 1639.21 His house was judged to be dilapidated and uninhabitable, yet his clothing included "quatre vieux pourpoints, un hault et un bas de chausses," two "chemisettes defutaine," five "chemises degrosse toile" and "un vieil caleçon de mouton passé en chamois."22 These entries tell us that those of lesser means owned garments similar to those of the upper social echelon but made of less expensive textiles.

18 The 1646 inventory of goods left by four sailors showed that one of them, Jacques Fleury, possessed similar items to those owned by wealthier colonists: bonnets de nuit, chapeau, and pourpoint were entered in his inventory, although all were classed as old. Moreover, the stockings he owned were made of serge rather than silk. One of Fleury's roommates, Jacques Figet, owned a new casaque and a new pair of purple stockings. Jean Fouchereau, another roommate, also owned a purple pourpoint along with a chapeau that had new cord, an indication of trimming being used to update, enhance, or repair an older item. Two of the men, Guillaume Lasur and Fleury, both owned souliers sauvages, the Amerindian moccasin used with snowshoes, although none of the latter were listed in the inventory.23

Contrats de mariages

19 A contrat de manage was almost always drawn up prior to a marriage thus it was a document that touched nearly all the adult population. Exceptions included indentured servants and apprentices.24 Whether the marriage contract was prepared for those of wealth or those with little, it is presented in the same precise and orderly manner as the inventory.

20 The first part of the marriage contract established the use, or not, of the Coutume de Paris, which stipulated the community of goods for the future couple.25 This was followed by substantial information concerning the future spouses and their parents including surnames, sometimes with pseudonyms, their professions, their ages in some instances, and where they lived and/or their origins in France.26 Then came several different clauses that focused on the material conditions of marriage that were the essential reason for the contract.

21 The marriage contract ends with a list of signatures of the contractants and witnesses present at the writing of the document, frequently a mix of both men and women.27 Some of these documents lead us to believe that the signing and witnessing of a marriage contract was a large social event: the marriage contract between François-Pierre de Vaudreuil and Louise Fleury de la Gorgendière in 1733 was witnessed and signed by no less than seventy-three men and women.28

22 One of the earliest marriage contracts found in Quebec archives was prepared in 1637, and shows that Abraham Martin and Marguerite Langlois gave their daughter Marguerite a trousseau valued at sixty-four livres which included two devanteaux.29 Her godparents were especially generous; their gifts to Marguerite totaled 460 livres including a wardrobe consisting of four cottes, a serge robe with tabliers, an hongreline, four pairs of bas, twelve chemises, fifteen cornettes, eighteen collets, eighteen mouchoirs de col, eighteen mouchoirs de pochette, three tabliers, two pairs of satin brassières, and two chapeaux.30 Also included were three gold rings, one with a turquoise.31

23 One of the most impressive and informative marriage contracts with notations relating to clothing and textiles is that of Geneviève Macart and Charles Aubert de la Chesnaye. The 1679 marriage contract lists not only all her clothing, but clothing that had belonged to her deceased husband, Charles Bazire. Her wardrobe is testament to her social position as wife of Bazire, receiver general of duties and of the king's domain.32

24 Macart's wardrobe reveals a mixture of garments, rich in textile and colour: "Un manteau à la vénitienne jaune et violet àfleurs" and "Une vieille robe de chambre couleur Citron double de taffetas noir." Also among her wardrobe were forty-one chemises, four of them decorated with lace. The number of headwear items is an indication of the importance of keeping the head covered night and day. Here we find forty-five coiffes, twenty-seven made of lace, five fashioned of prisonnière, and three of taffetas. There were also nine bonnets, ten coiffes de nuit, and ten cornettes. This is one of the few documents that show jewellery: Macart took to her new marriage an amber collar and a diamond cross.

25 Clothing that belonged to Macart's former husband included three habits, one made of silk lined with taffeta. There was also a justaucorps that boasted seventy-one silver buttons. Seven pairs of stockings were embroidered, one veste was made of brocade. Included in the list are thirty chemises, sixteen lace cravates and five lace rabats.33

Testaments

26 There were very few wills prepared in New France due in part to the absence of absolute freedom on willing: as already noted, the division of a legacy among heirs was predetermined by the Coutume de Paris. Thus, only those without living heirs would prepare a will.34 Wills in New France were made primarily to identify religious gifts, and make known the person's wishes as to disposition of the body.

27 The testator need not be ailing to precipitate the preparation of a will. For example, Louis Gasnier dit Bellavance prepared a will in 1673 prior to a voyage with Governor Frontenac. In addition to a monetary gift to the poor, Gasnier dit Bellavance left to his cousin Pierre Gagnier an habit valued at about forty livres along with three aunes of white créseau and three cravates. Claude Bouchard was designated to receive "environ neuf a dix aunes de toille de Meslis" along with "deux chemises de toille blanche et deux de toille des Meslis." Bouchard's wife was expected to spend four livres and ten sols to buy a pair of stockings made of fine étamine. Olivier Gasnier, one of several cousins, was also bequeathed two ecus, which were located in a pair of stockings made from white étamine.35

28 In his will, Champlain left several habits to various persons: to the mason Marin he bequeathed the last habit that had been made for him; to Bonaventure, his godson, he left "un habit de drap d'Angleterre, pourpoinct, hault et bas de chausse de même couleur," and to his valet Poisson he left an habit that was not yet finished but consisted of "un hault de chausse de bure avec une camisole de petite sergette grise et rouge."36 Jean Moreau, on the other hand, left a specific sum to be used to purchase an equally specific item: five livres ten sols were to be spent by Jean Allaire for a pair of French shoes.37

29 While inventories, marriage contracts, and wills do not give precise descriptions of the garments, the details as to textile and colour serve to validate our knowledge that the clothing and textiles used in France were being worn in New France during the same period. Indeed, this is one more piece of evidence in our quest to understand the clothing and textiles of the early Canadian colonists.

30 Moreover, archival documents like the inventaires des biens, contrats de mariages, and testaments offer insights into the lives of not only the wealthiest of colonists but of ordinary men and women. We can see where clothing for colonists of more modest conditions copied those of wealthier colonists differing only in textiles of more common varieties with less adornment.

31 In sum, the study of archival documents for colonists of the French regime show that Quebec costume and textiles differed little from those in France, providing evidence of a relatively closed society where innovations were neither encouraged nor cultivated and one which steadfastly remained true to its cultural roots.

GLOSSARY

- Bagnolette The bagnolette was a small hat knotted under the chin.38

- Bas The term bas came about as an abbreviation for bas-de-chausses, the masculine garment worn on the lower part of the leg. Bas-de-chausses were eventually known as bas and were made of silk, wool, and cotton.

- Bas-de-chausses These were originally identified as such to distinguish them from hauts-de-chausses, which covered the leg from the knee to the thigh.39

- Bonnet For men, the tonner refers to any type of headwear that was not a chapeau.40

- Bonnet de nuit The styles for both men and women were similar, a head covering without a brim, made of cotton or wool.41

- Brassière The brassière was a type of camisole widiout sleeves and was worn during the night by both sexes. It may have been quilted or fur-lined.42

- Bure This is a fabric with conflicting definitions. One description calls bure a very coarse woolen fabric with a long pile and sold at a very low price.43 Another definition refers to bure as a coarse, plain weave fabric woven with a cotton or hemp warp and wool weft.44

- Cadis This textile is named for the Spanish town of Cadix, its port of exportation. It was a serge made of wool, often in black or white, and was very inexpensive to purchase.45

- Caleçon Sometimes the caleçon was short, as in underpants, other times longer like a pantalon.46

- Calmande A very popular woolen textile with an infinite number of uses, calmande was manufactured in white, and may have been plain or patterned with flowers, dyed in the piece, or striped. It was very much in vogue in the eighteenth century in France. Calmande was made in Flanders and Lule from ordinary wool, and in Roubaix from a very beautiful wool that when woven appeared lustrous on one side like satin.47

- Camisole As a masculine garment, the camisole was worn over the chemise, under the pourpoint and was commonly made of cotton.48 When worn by women it was constructed larger, with more ease, and used as night clothing.49

- Cape The cape usually had a flounce and often had a hood; it could be made of precious fabrics and heavily embroidered.50

- Capot This garment appears to be uniquely canadien, and in Canadian literature it is spelled both as capot and capote. Regardless of spelling, it is a large garment worn over one or several other garments. Originally it had a hood that covered the head and face.51

- Casaque In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the casaque was slipped over the head and hung down as far as the hips — the distinctive garment of the Musketeers during Louis XIII's reign. Towards the end of Louis XIV's reign, the inconvenience of wearing a loose and flowing cape resulted in the wearing of a belt.52

- Chapeau The chapeau usually refers to a type of masculine headwear made with narrow or wide brims which could be fashioned from various materials.53

- Chemise As a masculine garment, this was a shirt, long in style and worn with manchettes at the cuff, lace at the neck opening. As a feminine garment, the chemise was worn next to the skin, was usually white, and often decorated with embroidery.54

- Chemisette The chemisette was a lingerie garment that covered the shoulders, hung to the waist, and had no sleeves.55

- Coiffe The word coiffe refers to a head covering. Men often wore coiffes under a hat or wig. They were made from numerous fabrics including taffeta, lace, muslin and gauze.56

- Coiffe de nuit See bonnet de nuit. These terms appear to be interchangeable in costume history.

- Colinette This was a type of bonnet worn by women when in the home.57

- Collet Originally, collet was a term applied to all garments without sleeves that laced or hooked in front on the chest.58 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries elderly women wore a neckpiece known as a collet to conceal the fleshy wrinkles of the neck.59

- Cornette The cornette was a type of linen headwear worn by ordinary women, in cotton or velvet for the bourgeoisie.60

- Corset This garment for the upper body may or may not have had sleeves. A decorative front was prominently displayed.61

- Cotte The cotte was a sort of tunic, generally worn open.62

- Cravate As neckwear, the cravate took on different styles according to the period. In the 1660s it was a rectangle of fabric knotted around the neck. By 1678 it was generally made of lace and tied in a bow. Towards the end of the century, the cravate ù la Steinkerque became fashionable, its end looped through a buttonhole.63

- Crémone This was a type of scarf made from soft cotton, muslin, or silk fabric used by women as decoration at the neck and shoulders. It was not worn knotted.64

- Créseau This textile was a woolen fabric, much like a serge. It was made primarily in Kent, England, as well as in Scotland for exportation to France and the colonies. On the continent, some créseau was woven in France and in Holland.65Créseau has also been described as a twilled, woolen fabric with a nap on both sides.66

- Culotte Generally thought of as breeches, the culotte had a fly opening buttoned with visible buttons, and horizontal crescent-shaped pockets. They buttoned on the outside of the knee where the jarretière was added.67

- Devanteau This is a regional term for tablier that originated in the west of France.68 The term devantiau was used in the regions of Cher and Nièvre until recently (1991).69

- Dormeuse This coquettish bonnet was reserved for sleeping.70

- Drap d'Angleterre Of the 207 textiles identified in my thesis research, this was one of several for which no definition could be found.

- Echarpe Séguin noted that in New France the écharpe was usually a piece of taffeta that women put on their heads; it covered the shoulders and provided protection against rain.71 Fashionable ladies wore the scarf with black fringes.72

- Etamine This very popular and simple fabric was woven of silk at Lyon and Avignon, of wool at Reims and of both silk and wool at a number of other centres. Étamine remained a fabric of various fibres into the twentieth century.73

- Éventail In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries fans were made of wood, ivory, and mother-of-pearl.74

- Fichu Women in the eighteenth century used the fichu as decoration at the neck and shoulders. It was made from soft cotton, muslin, or silk.

- Futaine Known primarily as a cotton fabric, futaine may also have been made of cotton with hemp or flax.75

- Habit Costume historians disagree regarding the pieces that made up the habit. In the seventeenth century, Boucher believes the habit for men was made up of two pieces (pourpoint and chausses), or three pieces (adding the manteau), or four pieces (including bas), all in the same colour and cloth.76 Leloir disagrees with the bas as part of the habit.77 At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the habit is said to include a manteau, veste, and culotte.78 By 1715, the three pieces had settled in to be justaucorps, veste, and culotte, continuing through the reign of Louis XV (1723-1774).79

- Hauts-de-chausses See bas-de-chausses. Under Louis XIII (1610-1643) hauts-de-chausses were very bouffant, tied at the knee with a ribbon. Later they became a wide, short pant cut at the knee.80

- Hongreline Much like a coat, the hongreline was a winter garment, the masculine version having a fur trim and fur lining.81

- Jupe In the seventeenth century three "skirts" made up the feminine costume: the secrète which was under the manteau, the friponne which was usually made of a rich fabric and bright colour, and the modeste. The modeste could be opened in front or closed by a series of ribbons.82 Thus, in the documents, use of the term jupe may be referring to any of the above.

- Jupon The jupon was shorter than the jupe and worn under it.83

- Justaucorps The justaucorps resembled a very long jacket and experienced a number of style changes over decades, particularly in the sleeves.84

- Manchettes As an accessory to the chemise, manchettes formed a very tiny cuff independent of the garment and were often made of lace and batiste.85

- Manchon The muff was originally made with fabric placed between two bands of fur on the outside and lined inside with fur. Later it became very large; some had a central ring in the middle that permitted them to be suspended from the waist by a knotted ribbon or strap.86

- Manteau As a masculine item, the manteau was a type of cape, worn down to the knees. It had a large collar to which cords were attached to allow the wearer to shift the manteau from one shoulder to another.87 As part of the feminine ensemble the bodice and skirt of the manteau were cut as one piece shoulder to hem, full in the back and front, and worn over a corser and underskirt.88

- Mantelet As a masculine garment, the mantelet was smaller than a manteau and had no sleeves.89 Séguin describes the garment in a similar manner noting that the custom of men wearing a mantelet made of calmande was practiced in an area from Pointe-aux-Trembles to Lamoraie in the Montréal area.90 As a feminine garment, it was a light shoulder wrap, generally short and sleeveless.91

- Mouchoir The handkerchief was entered in the documents as mouchoir, mouchoir de poche, or mouchoir de pochette.92

- Mouchoir de col Masculine and feminine item. As a feminine item, the mouchoir de col was usually made from a silk that resembled satin. It had no wrong side resulting in designs being worked on both sides. Few ordinary women owned them.93

- Pantoufles Similar to mules, pantoufles had no quarter, small flat heels or no heels at all and may have had fabric or fur uppers with leather soles.94

- Peignoir Reference to the peignoir in the documents indicate it was made of cotton, thus suggesting it was a simple nightgown.95

- Perruque The wearing of a wig began with Louis XIII (1610-1643) becoming an excessively large style under Louis XIV (1643-1715). After the death of Louis XIV the perruque became more compact.96

- Pinchina This woolen fabric from Spain was also made in the Toulon region where it was woven in a natural colour.97

- Pourpoint The pourpoint was worn on the upper body and usually was a quilted fabric padded with cotton. Up to the middle of the seventeenth century it was worn by all men; the shape and trimmings changed but the basic style and form remained the same.98 Paintings and illustrations of the pourpoint show it coming to a point in the front below the waist with full sleeves that may have been pleated.99

- Prisonnière A silk fabric that was very fine and woven to imitate gauze.100

- Rabat This large collar hugged the neck and shoulders and was bordered with lace. The two sides were squared and joined in front.101

- Ratine A twilled woolen fabric, the most appreciated of all ratines were those from Elbeuf.102

- Robe The robe was a woman's gown that took on many looks during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. See manteau, jupe, and jupon, which made up the feminine gown.

- Robe de chambre For men, the gown was a garment with long sleeves, secured at the waist by a cord or belt. It was worn only at home.103 In the seventeenth century the feminine robe de chambre was so named to distinguish it from the robe worn at court.104

- Serge Numerous serges were referred to by their fibres, such as wool or silk, by the number of shafts used for weaving, by their colour as in military uniforms, and individually from their place of fabrication.105

- Sergette A narrow textile made from a thin wool.106

- Soulier This term refers to French shoes.

- Tablier This type of apron formed a fashionable part of the feminine gown. The tablier may have been made from luxurious fabrics and decorated with ruches, lace, and embroidery.107

- Taffetas This textile was a very fine, soft silk, ordinarily very lustrous, tightly woven and made in all sorts of colours; it might be plain, glazed, or with stripes that included gold and silver.108

- Taffetas d'Angleterre In spite of the name, the textile taffetas d'Angleterre was made at Lyon. It was very strong, very lustrous, came in numerous colours and was sometimes striped.109

- Toile Included under this broad term for fabric are those made of hemp, flax, and cotton. Very often the place of manufacture was attached to the name toile.110

- Toile de Meslis Eight different spellings in the documents make identification of this textile difficult. Notaries may have been referring to Meslis de Bretagne where veil-like toiles were produced or to Mesle where a serge was made in white, beige, and black or to Meslay-du-Maine, a centre that specialized in cotton toile.111

- Veste The veste of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was more like a coat, with long sleeves, hung to mid-thigh, and was worn under the still longer justaucorps. It wasn't until late in Louis XV's reign (1725-1774) that the sleeves disappeared.112

* This article is dedicated to Dr Cécile Clayton-Gouthro: educator extraordinaire, mentor, dear friend.

Gown and habit design and construction by Jan Bones, Department of Clothing and Textiles, University of Manitoba. Photography by Allen Patterson, Imaging Services, University of Manitoba. Design and construction of the garments was taken from a painting (Antoine Watteau's L'Enseigne de Gersaint (detail), 1720, Berlin, Château de Charlottenberg) in Ruppert, Jacques, Madeleine Delpierre, Renée Davray-Piékolek and Pascale Gorguet-Ballesteros, Le costume français (Paris: Flammarion, 1996), page 136.

Some accents and spellings of French terminology have been changed by the author to reflect contemporary usage. In the following reference citations, however, French spellings in the titles of documents, etc., are cited verbatim.