Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

The Millennium Dome, Greenwich, London, England

Organizers: The Millennium Experience

Designer: Richard Rogers Partnership, built by engineers Buro Happold

Opening dates: 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2000

Admission: £20 per adult, £16.50 for children and students

Web site: http://www.dome2000.co.uk

Publication: Millennium Experience: The Guide (London: Millennium Experience, 2000). £5.

1 Greenwich, in southeast London, is known as the birthplace of time, the place from which all measurements of time and space are taken. The establishment of the Prime Meridian — Greenwich Mean Time — put Greenwich on the millennial map and at the centre of historical forces that would define Britain as one of the most successful maritime trading nations in the world.

2 This powerful heritage is reflected in the collections of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and in the historical collection of the Royal Observatory, which contains a magnificent series of prototype maritime timekeepers by John Harrison that enabled the first accurate measurement of longitude and hence the expansion of maritime trade. It is not surprising, therefore, that Greenwich was seen as a natural focus for a celebration of the end of the old millennium and the dawn of the new.

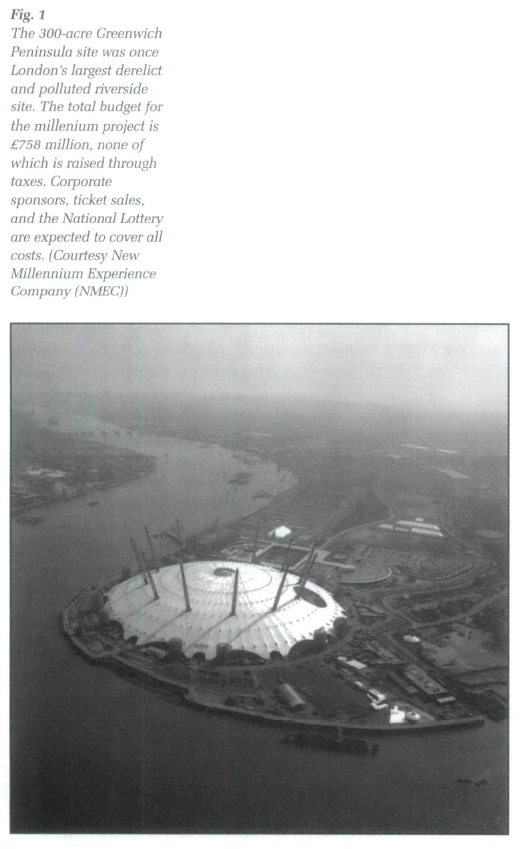

3 A 300-acre derelict brown-field site was located on the River Thames at Blackwall Reach, a few miles downstream from the palatial riverside buildings and park of historic Greenwich. The contrast could not have been more striking. The challenge was to create a contemporary exhibition celebrating the new millennium as a counterpoint to a historic vision of the old millennium (Fig. 1).

4 The Millennium Dome is one of the UK's largest construction projects. At the centre stands the Millennium Dome, the much-publicized exhibition venue designed by Sir Richard Rogers. The Dome's distinctive curved roof, clad in panels of glass fibre fabric, is the size of twenty football pitches. The space below could accommodate the Albert Hall thirteen times over. A massive enterprise by any standards, RIBA Journal called the construction of the Dome and the exhibits inside "one of the biggest combined efforts since the medieval cathedrals." When the magazines posed the question "How may people did it take to design the Millennium Dome?" it found that not even the client knew the answer. The magazine decided to photograph as many Dome designers as could fit into a studio and the group portrait comprised 120 individuals representing 41 companies!

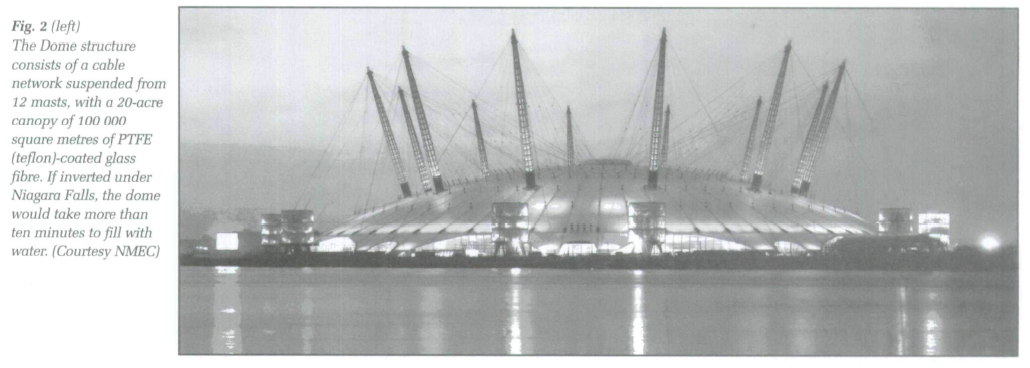

5 Whereas the medieval cathedrals were monotheistic statements of the insignificance of the individual, the Dome celebrates an individualistic age. The plethora of interactive exhibits emphasize personal control, and in spite of the huge size of the building, the interior feels no larger than a shopping mall. Unfortunately, there is no aerial viewpoint available to visitors that might correct this impression, although most British visitors will arrive with strong visual images in their mind, gleaned from massive press coverage over the last eighteen months. Indeed, for most British visitors, the Dome's reputation precedes it. The project has been dogged by political and creative controversy and the image of this pronged spaceship-like structure, lit up at night, must be one of the most recognizable of the year (Fig. 2).

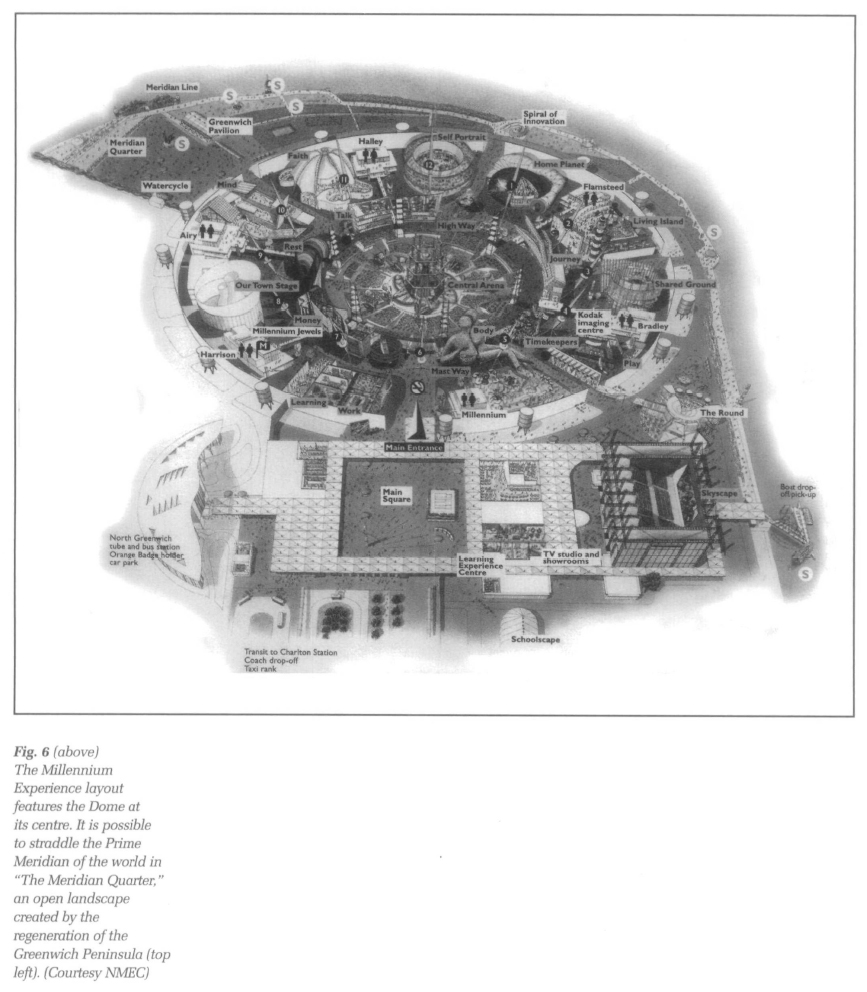

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 36 There are indications that negative public perceptions of the Dome are starting to change. Attacked by The Guardian newspaper two years ago as "a farrago of consultancy shite," the paper recently conceded that "it is not hard to draw an unfashionable conclusion: the Big Top will be a Big Success," a prediction that begins to look more and more unlikely. The impermanence of the Dome, the tent-like structure of the roof, the central performance arena, all conjure up an image of a circus. Some critics have suggested that the central area is much too big. The performance — a circus-like combination of aerial ballet and Olympic opening ceremony — was described by one designer as looking like a flea circus. There is no doubt that the eye constantly wanders. Obviously a theatrical blackout is not possible under a translucent roof canopy. At the Shakespearean Globe Theatre, a few miles downstream, performances are open to the skies but succeed by arranging spectators in close physical proximity, thus enabling actors to use eye contact to hold the audience's attention. Such an option is not available to performers in the Dome, of course. The central arena looks even bigger when empty, which is for most of the time, especially compared to the frantic activity and noise levels around the perimeter.

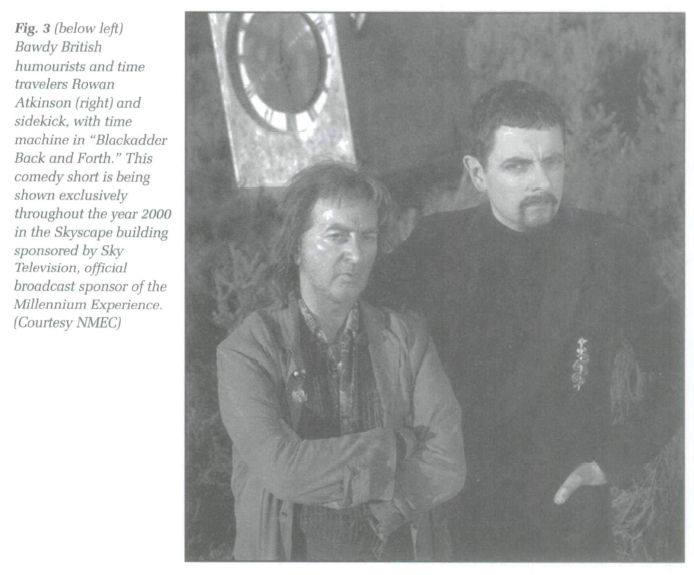

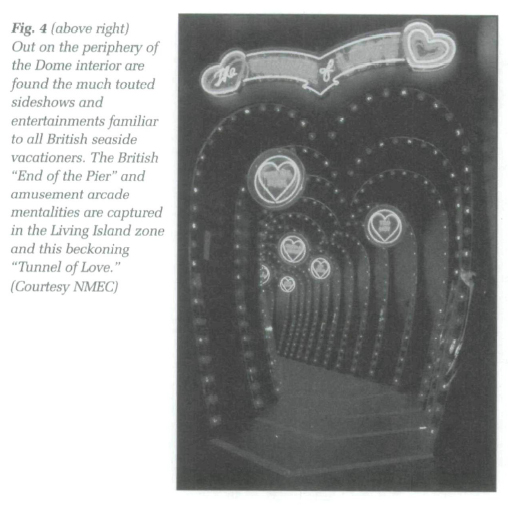

7 If the performance at the centre is a circus, then the exhibits around the perimeter are sideshows. The cacophony of noise — perhaps attributable to acoustics — has echoes of that very distinctive strand of British cultural life, the "End of the Pier." The raucous roll-up, roll-up of pier comedians and saucy seaside postcards, as George Orwell wrote in his essay on British humour, are the bedrock of British popular culture. In one of the exhibits, an animated brain wearing a red fez impersonates the comedian Tommy Cooper, who put so-called incompetence at the heart of much of British humour. Incidentally, the originator of "Mr Bean," arguably a comic descendant of Tommy Cooper, namely Rowan Atkinson, stars in one of the exhibition's "hits" — a short comedy film shown twice daily in the cinema complex next to the Dome (Fig. 3). One of the exhibits inside the Dome is based on a traditional seaside resort, complete with amusement arcades and a tunnel of love, albeit with an eco-message twist. Long lines of bus shelters at the entrance make the queue of visitors part of the exhibit itself (Fig. 4).

Display large image of Figure 4

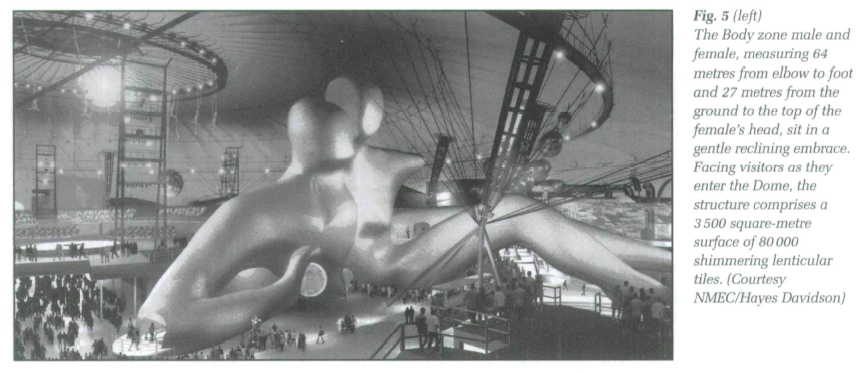

Display large image of Figure 48 There are eighteen exhibition zones in all — the exhibition's organizers recommend that visitors need at least five to six hours to see every one. The different zones are arranged around the perimeter of the Dome interior. Some bear the heavy hand of corporate sponsorship more than others. The Body zone, one of the most publicized attractions, features a massive structure depicting two reclining human figures. Visitors enter inside and move through special effects exhibits, experiencing, for example, an adrenaline rush in the Heart Room, where a huge model of a human heart beats realistically, if somewhat unnervingly, above one's head (Fig. 5).

9 The Faith zone features a cool white canopy and at the centre an igloo-like structure incorporating light sculpture by James Turrell. Outside the "igloo," crystal pillars display photographs and text describing how common human experiences — birth, death, marriage — are marked in distinctive ways by nine world faiths.

10 In the Home Planet zone, a seven minute "ride" simulates a journey through outer (and inner) space guided by animated aliens. In the Journey zone, displays featuring the history of travel, including a suspended model of Leonardo da Vinci's ornithopter, a penny-farthing bicycle, and the steam engine are featured alongside future possibilities such as bionic boots and future air travel. In the Talk zone, the history of printing, telecommunications, broadcasting and the Internet feature alongside 3-D photo-booths and virtual environments.

11 The Work zone examines the past and future of the world of work. Six core skills are identified as being essential for the future — communication, numeracy, problem-solving, IT, hand-to-eye co-ordination, and teamwork. Interactive exhibits test visitors' skills. Attendants dressed in ersatz sports gear shout instructions through microphones across the room — part gymnasium, part bingo hall.

12 The Learning zone features a larger than life school corridor complete with sights, sounds and smells. It includes a theatre space with a performance commissioned by the BBC, which discusses learning in relation to the achievement of goals. The Mind zone explores perception and illusion. It features an invisible sculpture (only visible by using infrared cameras) and looks at how minds communicate with each other, and the impact of collective thinking, a concept highly relevant to the concept of the Dome itself. The Mind zone also includes a colony of giant Leaf Cutter ants, and an Internet Web Stalker that visually maps the World Wide Web. Morphing machines allow visitors to change their race or age themselves by twenty-five years. The Money zone features a ceiling and floor lined with £50 notes. Visitors experience a dramatization of the worst and most extreme economic consequences of a society that consumes and indulges. There is a display of twelve of the world's rarest diamonds, including the 203-carat Millennium Star.

13 Also within the Dome are performance spaces for local communities. Each performance tells the story of a particular town or area in Britain. The World Stage project gives countries from around the world an opportunity to give a performance based on their own culture or history. Pageants, puppet shows, and orchestral performances are some of the entertainments scheduled to take place from over thirty countries worldwide. These projects give the Dome the air of an international eisteddfod, a Welsh cultural phenomenon not normally seen outside Wales. There is also a National Program of events and activities planned throughout Britain that will aim to create a lasting social legacy through educational and charitable initiatives (Fig. 6).

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 514 The future of the Dome itself is not yet clear. Six organizations have bid to develop the exhibition site for future use. The urban regeneration of the rest of the Greenwich peninsula continues apace with the construction of a Millennium Village, a new development that will include homes, shops, schools, medical facilities and work and leisure space.

15 As might be expected, the exhibition bears the evidence of the collaborative efforts of hundreds of different voices. It is perhaps inevitable that these voices do not always sing the same tune. Its problems (lack of a single-visioned overall impact, and sensory overload) and its successes (a celebration of individual choices and empowerment) are but two sides of the same individualistic coin. This cultural snapshot of Britain at the turn of the millennium is transient, existing only at this particular point in time. After all, one day the circus must move on.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6