Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'exhibitions

Finding Sense in New Places: Vital Signs in Contemporary Art Practice

Towards a Phenomenological Aesthetics

Curators: Display Cult (Jim Drobnick, Jennifer Fisher, Colette Tougas)

Duration: 30 March to 20 May 2000

Accompanying Conference: Uncommon Senses: An Interdisciplinary Conference on the Senses in Art and Culture, Concordia University, organized by Jim Drobnick and Jennifer Fisher with anthropologists Constance Classen and David Howes. Conference papers in process: three volumes entitled Vol. 1, "Sensation and Society;" Vol. 2, "Sensorial Aesthetics;" and Vol. 3, "Aural Cultures."

1 Phenomenology, as the study of human experience, is a school of philosophy that seeks to understand the world through various acts of consciousness. It calls for a renewal of our awareness of our subjective positioning and participatory actions, as living, feeling, and sentient beings. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, one of the most significant contributors to the philosophy, challenged traditional theories of perception and sensation, ultimately positing the body — the porous substance which seamlessly engages with the surrounding landscape — as the mediating ground between the natural world and one's understanding of it. Human perception, he argued, be it visual, aural, olfactory, tactile, or gustatory, provides us with our connection to the world. This perception is constituted by description, as opposed to analysis, by direct experience instead of distant or passive understanding, and by wonder rather than acceptance.

2 That the technologies of modern science have occasioned an estrangement from the sensual world is undeniable. It is not surprising that the ideas that would become the rudiments of a phenomenological movement would be articulated in the writings of early modern thinkers as influential, yet diverse, as Hegel and Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Freud.2 These inquiries into perceptual insight by the modern mindset are not limited to philosophers and psychoanalysts alone, however, as the phenomenological method was, undoubtedly, also at work in the process and paintings of artist Paul Cézanne. With its emphasis on sources of intuitive knowledge and modes of perception, phenomenology has since been recuperated in the practices of various disciplines. These range from anthropology and psychology to feminist theory, and, in this context, to aesthetics. Here surfaces of the body become the meeting ground for new dimensions of sensory experience.

Vital Signs: Embodying Contemporary Practice

3 The body was the primary mediating ground in the exhibition Vital Signs/Signes de vie, held at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery at Concordia University in Montreal (30 March-20 May 2000). Curated in conjunction with the international event "Uncommon Senses: An Interdisciplinary Conference on the Senses in Art and Culture" at Concordia University in April 2000, Vital Signs used the body to expand traditional notions of aesthetics by encouraging a multi-sensory engagement with the objects and installations within the gallery space.3 The exhibition was accompanied by a performative evening entitled Sentience: A Performance Salon, which featured a crossover of artists whose work was featured in Vital Signs, as well as some artists whose work was not.

4 Curated by collaborative team Display Cult (composed of Jim Drobnick, Jennifer Fisher, and Colette Tougas),4Vital Signs revealed how the non-visual senses are equally powerful agents in evoking memory through lived experience in works produced by nine different artists from across Canada and the United States. The sixteen pieces featured in the exhibition recalled the richness of human modes of perception in their combined appeal to the olfactory, the aural, the tactile and the gustatory, in addition to the visual and even the extra-sensory senses.

5 In positing a phenomenological aesthetics, the exhibition curators have challenged the hegemony of vision as the primary mode of perception in art practice and display.5 Such an aesthetic thus enlarges the terrain of contemporary art production while legitimizing this reformed practice within the very institution that supports ocular-centrism.6 The success of Vital Signs lay not only in its challenge to its gallery setting, but more broadly speaking, in its acknowledgment and endorsement of the manifold ways of learning and relating to the world.

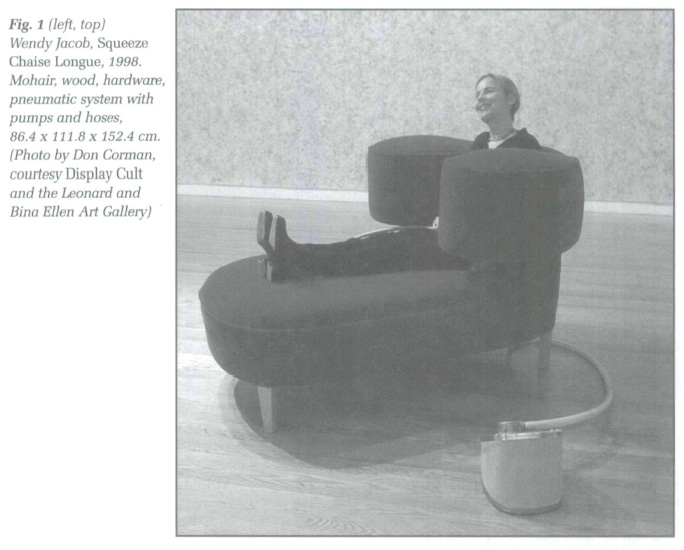

6 Vital Signs assembled a variety of artistic media, including variations of painting, sculpture, performance, photography, and site-specific and technological installations, which, through their very materiality, encouraged a visceral approach to the works in question. Wendy Jacob's Squeeze Chaise Longue, for example, is a Victorian-inspired chaise longue that has been recycled toward therapeutic ends to provide a haptic encounter between visitor and the object (Fig. 1).

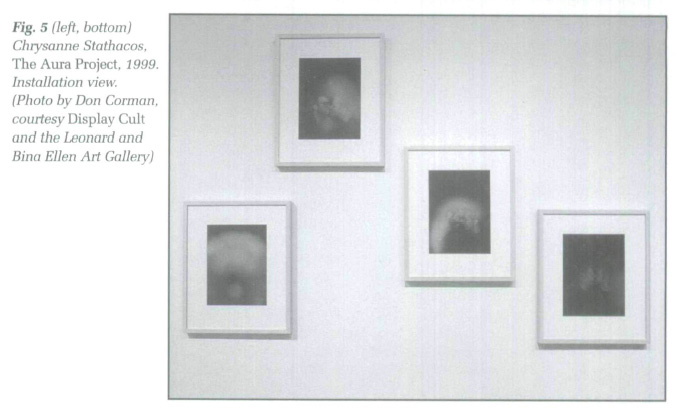

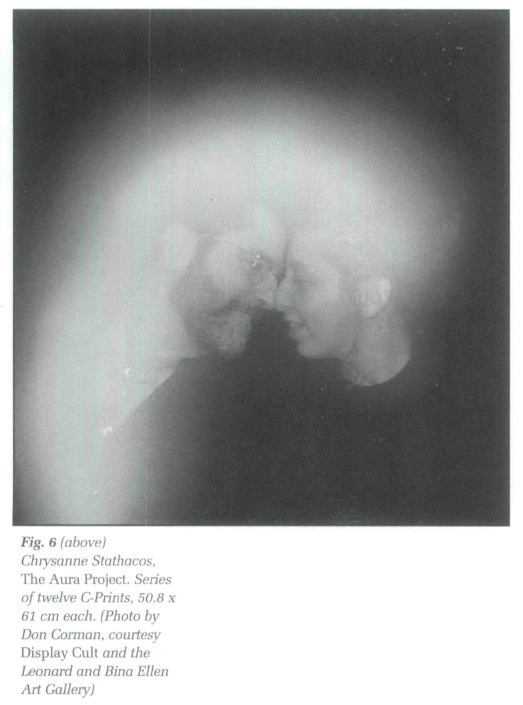

7 Jacob was originally inspired for the series of squeeze chairs and sofas she produces by the work of scientist Temple Grandin. In research she conducted on humane livestock treatment, Grandin found that applying gentle pressure to the animal's body would greatly reduce anxiety before slaughter; the ironic flip side of this finding is that it also makes the animal's flesh more tender for human consumption. Grandin applied these results to her own explorations about the human mental condition of autism, and developed a device capable of reducing an individual's state of nervousness from over-stimulation by providing a gentle squeeze, or surrogate "hug." Wendy Jacob re-interpreted Grandin's research in Squeeze Chaise Longue, a work that proposes a calming embrace by means of a prosthetic pump which inflates the arms of the chair to enclose the sitter. The acquiescent visitor reclines to have a hug administered to them by a second visitor, rendering this somatic object interactive on multiple levels. The work's formal elements — a chaise longue and its sitter — can also be read within a more traditional canon of art history where images of reclining women are abundant. An exception is noted in that Jacob's installation never allows for the complete objectification of its subject, as the sitter is her/himself capable of releasing the valve to disengage the device.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 38 Semiotically, the use of the chair carries with it innumerable associations: we cannot help but interpret the chaise longue within the context of Freudian analysis, or, in keeping with the Victorian aesthetic, as an extension of regal paraphernalia. However, like many works in Vital Signs, while the object may outwardly signify leisure and comfort, it has an underlying connotation that is somewhat more threatening, in the manner it constricts its sitter to a particular position, playing on attendant sensations that are almost pleasurably masochistic. In this regard, Squeeze Chaise Longue explores the precarious boundary between liberty and confinement.

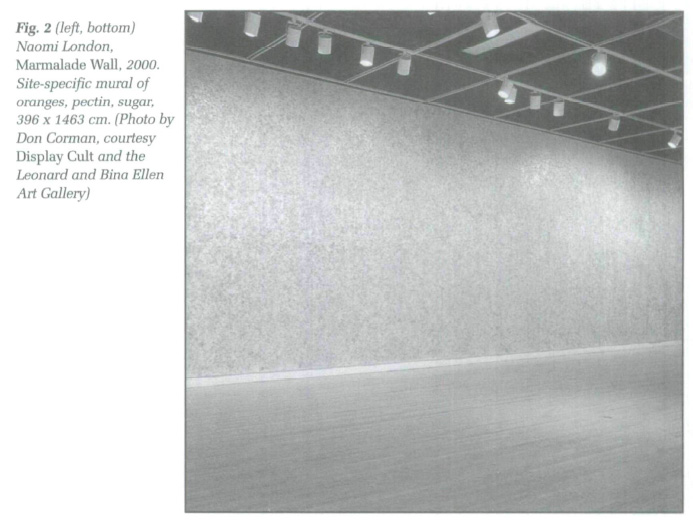

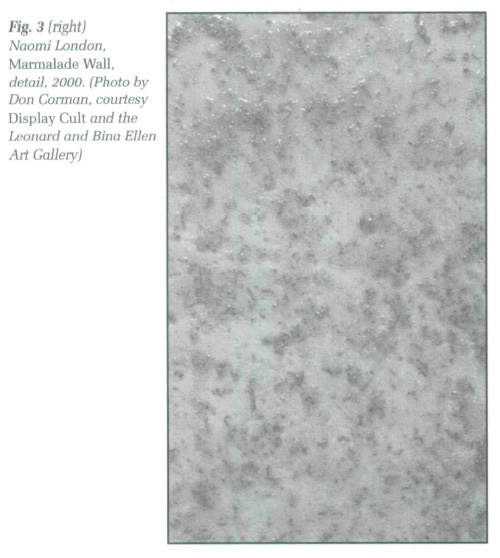

9 Opposite Squeeze Chaise Longue, Naomi London's monumental Marmalade Wall (3.96 metres by 14.63 metres) extended across an entire wall in the gallery (Fig. 2). The pattern of its glowing orange surface is faintly suggestive of ornate Victorian wallpaper. London's work both operates within traditions of art practice, and introduces important departures from it. By its impressive scale and in the manner of its making — created in situ on individual boards — Marmalade Wall immediately recalls Italian Renaissance fresco painting or the gestural tendencies of American Abstract Expressionists of the 1940s-50s. As for the use of food in art, it might be recalled in viewing this work how one enterprising artist inaugurated Swiss cheese to the artist's palette by spreading a melted version of it across a hotel room in New York City (Fig. 3).

10 But to dwell on formalist criteria is to neglect the work's ideological dimension. If, in scale and design, Marmalade Wall makes significant connections to existing artistic practice, London also problematizes this practice by reaffirming the important link between art and craft. These two forms of creative output are traditionally polarized, and, in the case of the latter, marginalized within modernist discourse as "women's work." In much of her oeuvre, London challenges this positioning of craft outside of mainstream art production, quite literally by celebrating the fabric of everyday women's culture. Thus, Marmalade Wall confounds the spaces, techniques, and materials of both practices, while simultaneously infusing the work with its dual focus on artistic production and domestic labour. By using a material traditionally associated with the domestic sphere in a non-utilitarian way (an impressive 83 industrial-sized jars of marmalade were necessary for this work), London thus produces an edible architecture that, quite literally, appeals to gustatory senses.

11 The simultaneous metaphoric and semantic references of the exhibition's title announced the multi-layered curatorial premise of the show. Firstly, this premise explores both how we perceive and the breadth of our perceptive abilities through the very senses that are, in this instance, equated with the body's essential functions (those that are habitually measured by vital signs). Secondly, we are led to examine the conventional signs and social/cultural constructs of artworks in the expanded terrain of a non-traditional aesthetic practice. This second signification is further apparent in deconstructing the space in whichVital Signs' phenomenological aesthetics was launched.

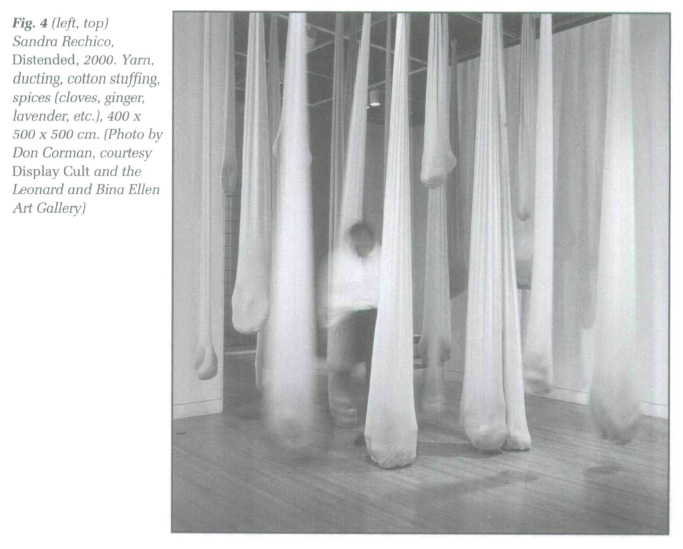

12 Taking to task the gallery-as-cube conception with its attendant sterile and impenetrable surfaces, Display Cult orchestrated a paradigm shift from public to private spheres, rooting the phenomenological inquiry of Vital Signs within evocations of domesticity. No sooner had visitors entered the gallery when they were met with the aromas emitted from the far corner of the gallery by Sandra Rechico's herb-filled stalactite hangings. Distended hangings magnify and explore the inner workings of the body: giant stuffed sacks suspend from the ceiling, recalling alternately organs, bowels, intestines, even testicles, with the effect that they both attract and repel the visitor in their arrangement and scale. Enclosed within these bodily casings are aromatherapeutic ingredients such as cloves, ginger, and lavender: herbs that are used to treat digestive disorders but which also recall those found in the home (Fig. 4).

13 It may not seem unusual to pair explorations of the body with the "haven" of the home, but just as phenomenologists presuppose the world to be an ambiguous realm, so too did this exhibition evoke the ambiguity of the place that is the private domestic sphere. At first glance, the gallery and curatorial arrangement of works had all the trimmings of a domestic setting. A grouping of twelve colour photographic portraits, hung like a portrait gallery and constituting Chrysanne Stathacos' Aura Series, brought Vital Signs' phenomenological investigation to the level of the extra-sensorial and the paranormal, each photograph chromatically revealing its subject's (or subjects') energy field like a modern-day halo (Fig. 5). Sitters for these photographs are asked to place their hand on a metal plate which "reads" the skin's moisture, temperature, and galvanic response; this information is then translated and relayed on the photograph as a chromatically-charged aura. The tension in these works arises in the tripartite interplay between the technological method of the medium of photography, the paranormal or sixth-sense information that this medium reveals, and the quasi-religious composition of the sitters and their exposed life force (Fig. 6).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

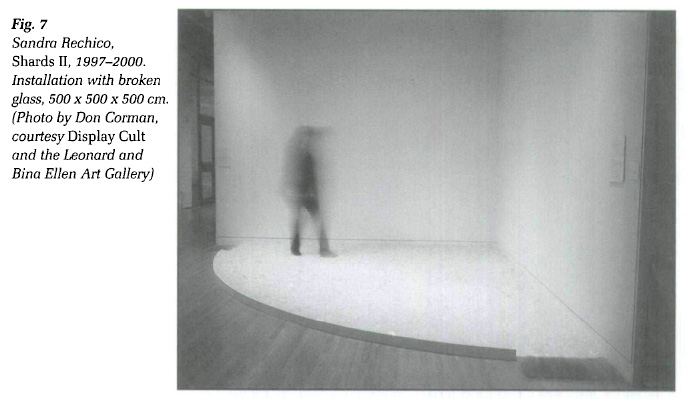

Display large image of Figure 614 The combination of Stathacos' work, Jacob's Squeeze Chaise Longue, and the warm glow of Naomi London's Marmalade Wall interacted as poignant if not romanticized reminiscences of harmonious living spaces and familial rituals. Like the bitter-sweetness of the citrus preserve, however, the first impression was but a partial representation of the dynamics of domesticity, which is not always the safe, secure place we imagine it to be. The seductive qualities of these domestic renderings were ultimately revealed for the fragile illusions they may in fact represent. Further forays into the gallery ruptured these initial moments of domestic bliss. Claire Savoie's audio installation, entitled Mon Coeur, projected into the gallery (amongst other noises) the sound of crashing dishes, an image which can be visually and experientially confirmed when encountering a second work by Sandra Rechico. Her weighty installation of crushed glass, Shards II, confronted the visitor on the other side of the gallery's dividing wall. Where Savoie's recording invokes the architecture of the home through the sounds of the everyday, Rechico's 1100-kilogram pile of broken glass uses memory to suggest both routine and ritual references. The fragments imply a range of creation, from accidental breakage in everyday use to diverse cultural and celebratory practices of plate and glass smashing (Fig. 7).

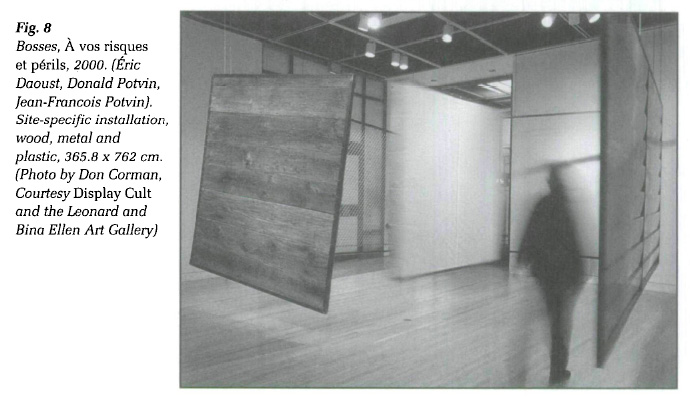

15 The ambiguity of the domestic sphere was more fully articulated in the site-specific installation of architectural collaborative Bosses' À vos risques et périls. Practising an architecture that provokes reflection on the built environment, the trio Eric Daoust, Donald Potvin, and Jean-François Potvin have designed three imposing architectonic frames that suspend menacingly from the ceiling and swing with guillotine precision in the powerful wind generated by two nearby fans activated by the visitor's approach. There is the potential for severe bodily danger to any visitor who does not respect the physical trajectory of these oscillating structures, dispelling the myth of the home as site of safety. More so than in other works in this exhibition, visitors are acutely aware of where they position themselves within the sphere of this installation, as its title aptly suggests. The combined effect of the sudden drop in temperature produced by the fans and the speed of the moving structures renders the possibility of a physical encounter with these frames threatening and forces a heightened awareness of the body's presence in space.

16 Like London'sMarmalade Wall, Bosses' installation makes reference to traditions in art practice, recalling in form hanging mobiles. In their combination of new and recycled industrial materials (wood, metal, and plastic) however, they are perhaps closer in lineage to the dislocating and hostile steel sculptures of Richard Serra. The use of tarp, wood, and chain-link fence introduce materials familiar to the domestic paradigm. However, their arrangement and the trajectory of their rotations force the visitor to carefully negotiate the space of this work. As an architecture of interaction, these frames successfully problematize overly facile interpretations of the home as protective shell (Fig. 8).

The Space of Learning

17 Ultimately, the question to be asked is what role a phenomenological aesthetics does and can play in museums and gallery settings. To assert that contemporary art practice has been enriched by its exploration of diverse forms and techniques devised to engage the non-visual senses is not to detract from the significant impact these critical art forms have had on audiences whose engagement is solicited in creative and innovative ways. Works operating on the level of direct sensory experience provide a welcome change from the conceptual and ocular-centric orientation of a modernist tradition where reductive aesthetics has privileged mute surfaces over the richness and sensuousness of layered, multidimensional ones. And while, historically, art museums and galleries have all but institutionalized the divide between artist, artwork, and visitor, a phenomenological aesthetics proposes a direct challenge to these institutions, by broadening the terrain of contemporary artistic practice.

18 When viewed within the broader framework of social and cultural industries, to practise a phenomenological aesthetics is to acknowledge the manifold ways in which learning and apprehending occur, and which today have gained credence in many other settings. Whether such an aesthetic practice would ever be capable of overcoming the hegemony of vision in order to reconcile a sensory-deprived society is less instructive than asking how this vision has shaped and narrowed our experience of the world. As Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa has so compellingly argued in a recent lecture at McGill University's School of Architecture, it is not enough to critique the ocular-centrism of contemporary culture without also identifying the nature of vision it privileges. This too has shifted over time: commensurate with a culture that values progress and speed over processes that encourage a more deliberate form of discovery is a notion of vision that is highly focused and reductive.7 Certainly, in the manner it provokes a re-awakening of the senses, the multidimensional, multi-sensory artwork in this exhibition rewards the viewer with a deeper understanding of the self. In its insistence on alternative modes of perception, the space of Vital Signs provided a place to dwell in the world in which we live, while making sense of things we cannot see.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8Curatorial Statement

19 Given that the senses of taste; touch and smell are so consistently neglected in critical and cultural discourse, we felt that if we were to examine them at all, it was essential to do so in a varied and compound manner, that is, aesthetically, performatively, and theoretically. Vital Signs, then, was one component of a three-part, multivalent project exploring how the non-visual senses are being both interrogated and reconceived in contemporary artistic practice. This exhibition was accompanied by "Sentience," a performative salon, which featured six simultaneous interactive performances that engaged the audience's sensory modes directly. Concurrent with these artistic events, we organized an international academic conference, "Uncommon Senses: An Interdisciplinary Conference on the Senses in Art and Culture," held at Concordia University. This three-day symposium brought together 185 speakers from the fields of art history, philosophy, anthropology, performance studies, religious studies, and cultural studies, among other disciplines. Presentations addressed the subtle but powerful links between the senses, lived experience, cultural difference, and aesthetic meaning.

20 The title of the exhibition, Vital Signs, embodied two metaphorical dimensions: one medical, the other semiotic. The work in this show aimed to take the pulse of a certain type of contemporary art practice that exemplifies a shift in sensibility toward the experiential. The artists presented here engaged in a phenomenological aesthetics that favours immediate sensory experience yet also provides challenges to social and cultural assumptions about perception. While the non-visual senses may appear to operate "transparently" in perception, there is a politics of the senses at work which raises issues about how knowledge is produced out of encounters involving the body, history, memory, representation and culture.

21 Vital Signs also problematized and provided an alternative to recent conventions of interpreting and responding to artworks in exclusively visual or linguistic terms. The uniquely mutable status of artworks incorporating the non-visual senses calls for a new conceptual framework that can articulate how they function simultaneously as a material and an idea, a stimulus and a sign, an object to be interacted with, and one that is transformed in the very act of apprehension. In other words, olfactory, gustatory, tactile and acoustic artworks generate signs with vital properties that confound the habits of distance characterizing traditional aesthetic apprehension.

22 This exhibition juxtaposed site-specific installations, interactive sculptures and technology, performance, photography of the invisible, and painting with atypical substances. Not only were each of the five senses explored, but also senses not widely recognized and bordering on the paranormal. In contrast to the sensory calm that pervades the "white cube," Vital Signs sought to engage its audience with a sense of diversity and cacophony via the nose, tongue, skin and ear.

23 Ultimately, with this multidimensional approach, we wanted to pose a series of questions that we are still in the process of investigating: What lies beyond the scope of the aesthetic gaze? How do artworks involving taste, touch and smell transgress and reconceive definitions of art? In what manners can difference be mobilized to counter and reconfigure hegemonic understandings of the senses? Abandoning the conventions of discrete objects and visual detachment for artworks that change over time and involve elements of corporeal intimacy can sometimes raise challenging and provocative legal, ethical, and environmental questions. And when* prevailing cultural paradigms assume that the so-called "lower" senses are always-already marginalized and abject, it can be a surprise to experience fragrance, food and texture in meaningful and elegant artworks. Vital Signs, and the events associated with it, foregrounded these and other issues, bringing attention to the significant ways in which the non-visual senses contribute to identity, culture and artistic practice.