Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

The Eva and Morris Feld Gallery, Museum of American Folk Art, Millennial Dreams: Vision and Prophecy in American Folk Art

1 An angel blowing a trumpet heralds Millennial Dreams: Vision and Prophecy in American Folk Art at the Museum of American Folk Art in New York City. This suspended sculpture dominates a short hallway graced with weathervanes and sets the scene for a verse from Revelations projected on the floor: "And I saw an angel come down from heaven, having the key of the bottomless pit and a great chain in his hand. And he laid hold on the dragon, that old serpent, which is the Devil, and Satan, and bound him a thousand years..." This dramatic introduction encapsulates the theme of a well-presented exhibition exploring prophecy and Utopia in American folk art.

2 The text accompanying various other trumpet-blasting angels introduces the central theme of the exhibit: the influence of the idea of the "millennium" in American history and culture. As the text explains, American folk art is replete with Judeo-Christian visions of a millennium as both "a long-awaited period of peace, harmony, and abundance" and "the end of time itself." Using an impressive array of materials, the exhibit shows how Americans have interpreted both visions, from prophecies of the apocalypse to attempts at creating a heaven on earth.

3 On the whole, the layout and design of the exhibit permits the creative presentation of sometimes unwieldy artifacts and allows for effective use of limited space. The curator selected not only paintings and sculpture but also clocks, chairs, quilts and maps to convey the sense that folk artists have a deep and longstanding interest in millennial and Utopian themes. For the most part, the texts describing these pieces perform an excellent job in combining ethnographic, religious and artistic explanations. Furthermore, the concept of two central "millennial dreams" — apocalyptic and Utopian — is expressed by the use of colour and light in the galleries themselves: the first space, which contains the art and artifacts that seem more concerned with the end of time and an imminent day of judgement, is painted a deep eggplant colour; whereas the second space, with its white walls, high ceiling and skylight, contains materials concerning attempts to create a heaven on earth before the eventual day of judgement.

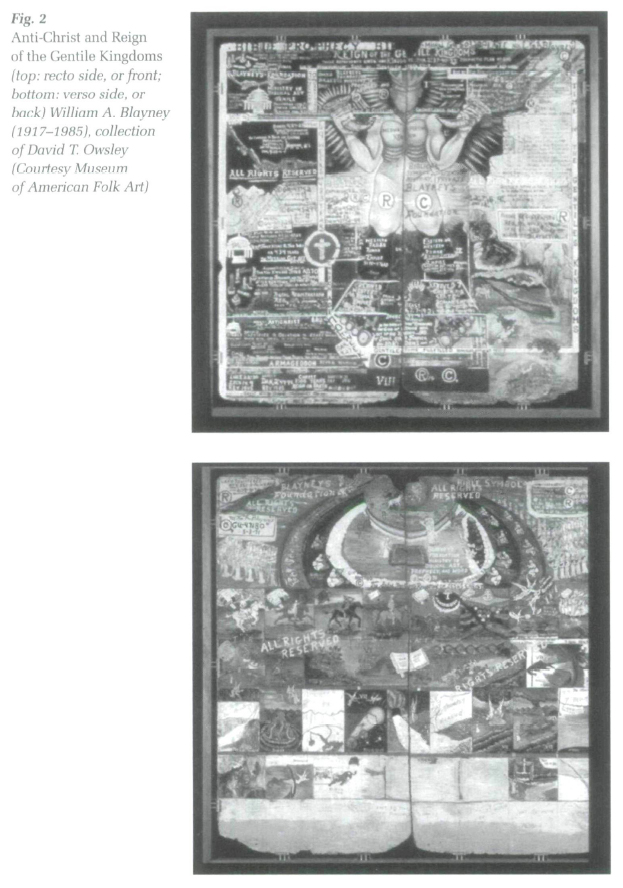

4 After running the gauntlet of Father Time, Michael slaying the Dragon, silent angelic trumpeters and the ominous floor projection, visitors come to a dramatic free-standing display wall that houses two double-sided paintings by William A. Blayney. Because the two are suspended between panes of glass, both sides are visible, allowing the visitor to enjoy the full effect of the multi-coloured visions of Judgement Day. On the other side of the wall, flanked by the Blayney pieces, is a photographic reproduction of Bible Quilt by Harriet Pomers, a former slave in Athens, Georgia. The quilt was too fragile to survive travel and display, but the reproduction does ample justice. Even better are three individual blocks from the quilt with accompanying text related to Pomers. The use of both the illiterate artist's words (recorded by an acquaintance recognizing their value) and the individual blocks more than compensates for the lack of the actual quilt.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 Facing this display is a wall covered with maps and charts. These items derive mostly from the Millerite movement. William Miller convinced his followers that the millennium would start in the 1840s. The charts explain his theory through mathematical calculations and biblical imagery. As if to provide even more proof for the coming of the end of the world, a quote from the Book of Revelations is painted high up on the wall: "And Lo, there was a great earthquake, and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became like blood, and the stars of heaven fell into the earth." The quotation is so high off the ground that it may easily be missed. However, the effort of craning one's neck to read such dramatic words creates an aura of being in attendance at a fire-and-brimstone sermon.

6 Nearby, a rectangular space generates the peculiar impression of a combination of a Buddhist temple and an apse in a cathedral. This was due to the shape of the gallery and the presence of a bizarre and intriguing display at the far end of the space. This piece is part of The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nation's Millennium General Assembly by John Hampton; the rest of the 11.5 metre display remains at the National Museum of American History. Made of found objects such as chairs, lightbulbs and dishes all covered in silver and gold foil, the Throne is just that — a fantastical assembly room, topped off with crowns. Accompanied by paintings by other artists entitled The Wages of Sin and The Book of Revelation, the overall effect is quite remarkable.

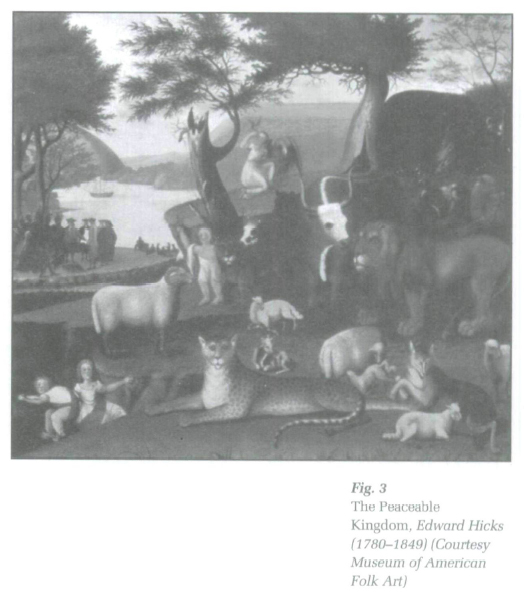

7 While these design decisions all enhance the content of the artwork, the most effective display is the series of Shaker ladderback chairs suspended from the ceiling in the next gallery. Ascending gracefully as a man-made ladder towards the skylight, the chairs appear as a modernist sculpture. The accompanying text quotes religious writer Thomas Merton, who wrote in 1966 that "the peculiar grace of a Shaker chair is due to the fact that it was made by someone capable of believing that an angel might come and sit on it." The cosmology of the Shakers that, according to Merton, encompassed "creativity and worship" is well represented by this simple yet evocative display.

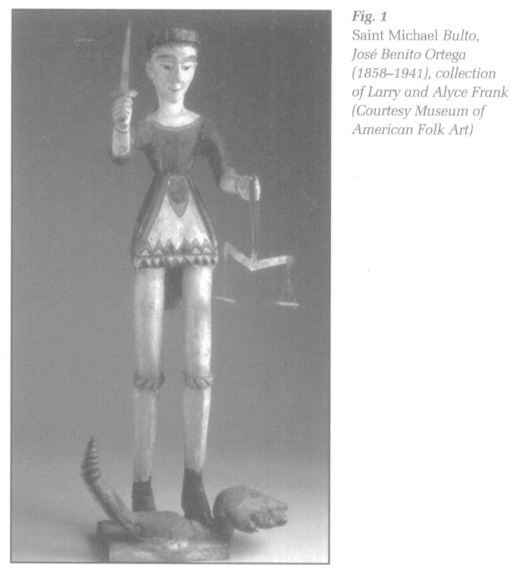

8 The exhibit design is not without its flaws, however. Some of the text fails to fully explain the significance of the art. For example, text accompanying a wall of Shaker drawings repeatedly calls them "gift drawings," yet makes no reference to either the term itself or the symbolism of the artwork. Another drawback is that the display case of mid-nineteenth-century Bultos and Retalbos, small wooden sculptures and icons from New Mexico, is partially concealed behind the structure of the entrance hallway. It is a shame that these pieces (which one visitor claims he prefers to works by Picasso) are easily missed. Two other criticisms regard omissions: while the lecture series accompanying the exhibit includes gospel music, it would have been a welcome addition to integrate music — spirituals, Shaker hymns, etc. — into the exhibit as a whole. Another possibility might have been to include recorded versions of famous orations and sermons addressing the exhibit themes.

9 The most egregious display problem is the use of glass on Horace Pippin's Peaceable Kingdom. This dark painting is protected by glass but the glare from the lights creates distracting reflections. This makes it very difficult to see the ghostly figures in the background — of a lynching, soldiers, and gravestones — that greatly complicate the pastoral foreground scene. Both visitors and museum staff on hand agreed that the use of non-reflective glass (or no glass at all) would have solved this problem detracting from the enjoyment of one of the exhibit's strongest pieces.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 210 Despite these flaws, the exhibit is effectively designed overall. But it is the art itself that does the best job of illustrating the power of "millennial dreams." The exhibit curator takes the position that this fascination with a "divine plan," and a society's role in it, may in some ways be unique to American culture. An introductory panel quotes Thomas Paine as saying that the young country had the "power to begin the world over again." Whether or not one agrees with this exceptionalist viewpoint, the array of artwork is impressive and attests to the power of millennial thought in American culture.

11 Several pieces evince the first main theme: that of a heaven to come. Photographs of Puritan headstones, intricately carved with skeletons snuffing out candles, are situated across the room from the Hispanic sculptures of Saint Michael who has the scales of judgement in his hand (Fig. 1). The juxtaposition of these two cultures, both anxious about the chances of salvation, reminds the visitor of the diversity of an American culture that nevertheless shares some common beliefs.

12 Other pieces are more outspoken in their vision of imminent judgement. The works by Blayney are evocative of a cross between a painted VW bus and an Hieronymus Bosch painting; Blayney interpreted the Book of Revelations literally in dense and vivid detail (Fig. 2). In comparison, John Hampton's The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nation's Millennium General Assembly evokes a vision of a majestic yet placid group of celestial visitors, obediently sitting in their reserved seats. Both artists evoke a coming Judgement Day, but Hampton, while certainly quirky, is relatively calm in comparison to Blayney's cataclysmic hysteria.

13 Likewise, Pomers' Bible Quilt presents the coming judgement as an inevitable truth but, unlike the terrible scenes or glittering assembly envisioned by Blayney and Hampton, hers is a more familiar vision. According to Pomers, elements of the millennium have already come to pass. For example, she sewed a quilt block describing a meteor shower that actually happened, calling it The Falling of the Stars on November 13, 1833, and is quoted as saying that on that night "[t]he people were fright [sic] and thought that the end of time had come. God's hand staid the stars. The varmints rushed out of their beds." Perhaps, having been enslaved, Pomers had no need to imagine apocalyptic horrors, and instead saw the millennium as a form of deliverance, guided by a God who could control the stars in the sky.

14 Another vision of the end of time is visible in a more recent and very curious painting (A Woman Shall Compass Man, 1978) by Harold Finster, Baptist preacher and self-proclaimed "man of visions." It portrays a giant smiling woman in bright clothing and heavy boots who is capable of lifting churches off the ground with ease. On her sleeve it reads "she will pick them up and sit them down before the end," on her boot it says "woman power in men shoes," and a tiny person at the door of the church yells "Hey, set the castle down!" More text explains that "[w]omen shall out number man and growing great power before the end of earth's planet." The curator interpreted this to mean that the increasing social and economic power of women is a prelude to the millennium. His note is cryptic, however, and does not offer an opinion as to whether Finster finds "woman power" to be a desirable development.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 315 The exhibit's second theme, that of the possibility of creating a heaven here on earth, is exemplified by artifacts from the Shakers, Quakers, Church of Latter-day Saints, along with other lesser-known "intentional communities." The combined effect is one of hope for a better world through the creation of Puritanical "cities on a hill." C. C. A. Christensen's Handcart Pioneers of 1900 depicts the westward journey on foot by the followers of Joseph Smith on their way to the Salt Lake valley. The details in the painting — a woman gathering buffalo chips for fuel, a child on his father's shoulders, a woman nursing a baby — personalize the individuals who sought to create their ideal society. Next to Handcart Pioneers is Bishop Hill from the North by Olof Krans, painted years after the community founded by dissenting Lutherans in the 1840s failed. It was, evidently, important to Krans to document the attempt at a perfect society. Across the gallery is a drawing of another attempt at creating a Utopia, a Shaker drawing of the town of Alfred, Maine, with clear, numbered buildings and explanatory text. The shutters on the neat buildings are drawn in sharp detail but the mountains in the background are hazy. This suggests that the town's inhabitants held little interest in the imperfect world beyond their own. The views of each group, most likely, would have clashed with one another. Imagine the roiling theological debates between the artwork after the museum closes!

16 On the rear wall of the gallery hang three interpretations of Isaiah 11:6, which is printed on the wall above them: "The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together, and a little child shall lead them." All three are entitled Peaceable Kingdom. The first, from 1865, is an ink-on-paper drawing by Dr William Hallowell, a Quaker physician, who wrote the above verse around his oval drawing. The second is Edward Hicks' familiar rendition of the same theme from 1846-48, a calm image of peace and security (Fig. 3). But the third, by Horace Pippin, dated August 9,1945, adds an element of danger to the otherwise pastoral triptych. Pippin, acutely aware of the horrors of our modern world, shows African-American shepherds with their peaceful flock, watched by menacing shadows in the background. The shadows serve as reminders of the experiences of African-Americans. The date of the painting itself is that of the bombing of Nagasaki. The effect is of an uneasy peace — who knows if, despite the best of intentions, the lion will suddenly turn on the lamb?

Display large image of Figure 4

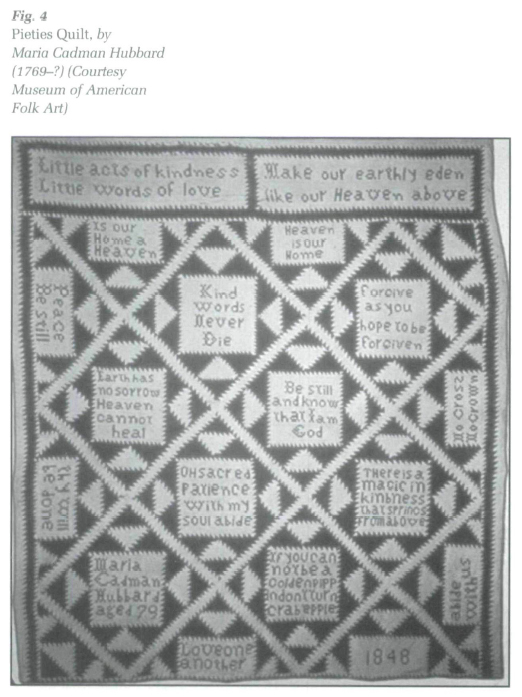

Display large image of Figure 417 Facing these paintings is a large red-and-white quilt made by Maria Cadman Hubbard and finished in 1848 (Fig. 4). Pieties Quilt is covered with aphorisms such as "if you can not be a golden pipp — dont turn crabapple" and "forgive as you hope to be forgiven" pieced out of red and white cloth. The saying in the upper right corner sums up the entire exhibit: "Make our earthly eden like our Heaven above."

18 The selected mediums represent a broad period of American history and show how Americans have long been preoccupied with the hopes and fears of their faith. This would have been further strengthened if the exhibit had included more work by artists of other faiths. There is only one piece by a Jewish artist (Daniel in the Lion's Den, 1949, by Morris Hirshfield) and none at all by Native Americans. The reliance on works exhibiting Protestant and a few Catholic beliefs are perhaps expected, given the dominance of Protestantism in American history over the last three hundred years. An even more diverse representation of cultures and artists would further support the curator's argument for the widespread power of vision and prophecy.

19 Another issue to consider is that the materials from Utopian religious communities are presented from a rather romantic viewpoint. It might complicate the picture to consider that, at the time, some of the groups mentioned were considered deviant and that communities were formed in self defense. Current groups that intend the same are often considered dangerous cults. Given today's recent violence surrounding the Branch Davidians and the concern over bigamy and child abuse among Mormon extremists (who are refuted by the established Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), we should bear in mind that Utopian visionaries of yesteryear would likely be found on today's FBI "Most Wanted" list.

20 While there are some significant caveats, Millennial Dreams is a fascinating and timely exhibit. The combination of a wonderful range of art presented creatively serves to convince the visitor of the historical power and ongoing influence of ideas of vision, faith, prophecy and hope in American culture.