Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Canadian War Museum's Airborne Beret Collection

Canadian War Museum's Uniform Collection

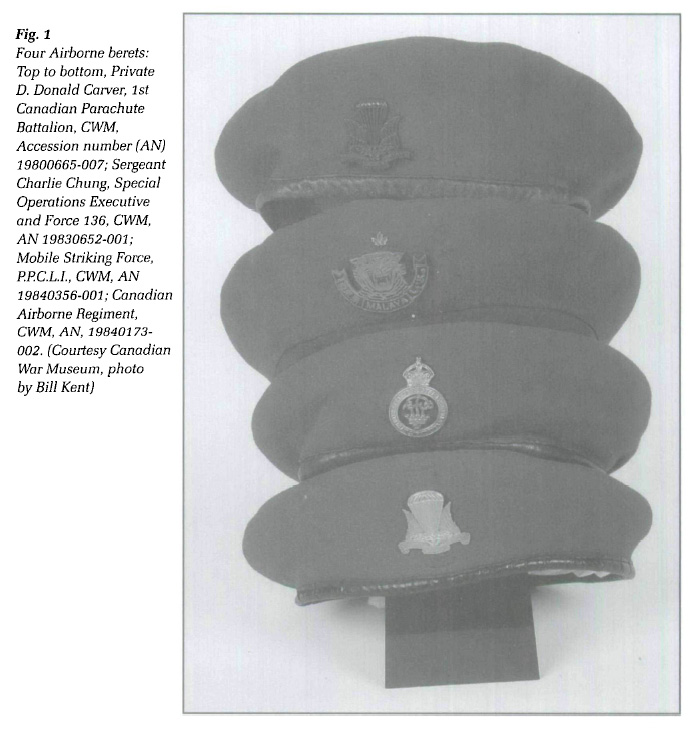

1 Over the years the Canadian War Museum (CWM) in Ottawa has acquired, arranged, and catalogued over 35 000 items for its uniform collection. The headdresses alone total 5 891 items. In January 1998, a study revealed that this collection contained forty maroon berets.1 They were acquired by the CWM between 1967 and 1988. Of these, thirty-two berets document Canada's Airborne history from 1942 to 1974 (Fig. 1).

2 This article will examine the origin of the beret, the origin of the British and Canadian Airborne Forces, the origin of the maroon colour and the adoption of the beret as the official headdress for the British Airborne Forces, the adoption of the maroon beret by the Canadian Army, the manufacturing of the first Canadian maroon berets and the first issue of maroon berets to 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion personnel. In addition it will present an overview of the CWM's Airborne beret collection and show how it documents the different eras of the Canadian Airborne history; a detailed examination of Corporal Frederick George Topham's and Sergeant Charlie Chung's Airborne berets; and an in-depth analysis of the parts of a beret, the manufacturers and Ordnance markings stamps, and the authorized and unauthorized modifications carried out by paratroopers to their maroon berets.

Symbolism of the Military Headdress

3 Throughout history, the headdress has been the most distinctive, varied and visible part of the uniforms of every country's armed forces. For soldiers, the headdress was much more than an article of clothing. It was a symbol of their collective identity. The headdress reflected their unit's cultural and ethnic legacies, esprit de corps, identity, pride, reputation and tradition. Among the thousands of headdresses produced throughout the centuries, the maroon beret, despite its short existence, has very quickly earned a special place in the annals of military history.

Origin of the Beret

4 The first berets were worn by members of the Royal Tank Corps in 1924. A few years later, in 1928, the 11th Hussars were issued their berets. They were worn without a badge, a privilege granted to the regiment by King George VI. The British Airborne Forces received their berets in 1942. Other British units were issued their new headdress between 1942 and 1944. Each had its unique colour.2 Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein did much to popularize the beret as he regularly wore the black beret of the Royal Tank Corps.

Forging the Airborne Identity

5 The origins of the Commonwealth Airborne Forces go back to the first year of the war. On 22 June 1940, on instruction from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, General Hastings Ismay, head of the Military Wing of the War Cabinet Secretariat, ordered the War Office to raise a corps of at least five thousand parachute troops.3

6 The origins of the Airborne Forces in Canada can be traced back to an August 1940 memorandum from Colonel E. L. M. Burns to Colonel J. C. Murchie. Impressed by the successes of German parachute units during 1939-1940 campaigns Burns recommended the formation of a Canadian airborne unit. His enthusiasm however was not shared by National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa where the high command favoured the formation of defensive rather than offensive units. Analysing the situation, Burns re-submitted his idea and underlined that the parachute unit could be used as an internal security force to protect Canada. It took two years to convince various levels of National Defence Headquarters that raising such a parachute unit was necessary.4

7 On 22 April 1942, during a question period in the House of Commons, the Hon. James Layton Ralston, Minister of National Defence, stated, "... the formation of paratroop units is not being gone ahead with at the present moment, but rather the training of men so they can be used as paratroopers when the time comes, with the additional training to be done with aircraft, except the jumps which are done from the tower."5

8 On 27 June 1942 Brigadier E. G. Weeks, Deputy Chief of the General Staff, announced at a press conference the decision to organize and train a parachute battalion using U.S. facilities and training methods. In order to assess the current parachute training available, one group was sent to the Fort Benning Parachute School in Georgia, and a second group to the R.A.F. Parachute Training School in Ringway, England.6

Origin of the Maroon Colour

9 There are several accounts of the origin of the maroon colour for the British Airborne beret. The version that the Airborne Forces Museum, Browning Barracks, Aldershot, Hampshire, England, considers as true is the following: "A tradition within the British Army has always held that the Colonel of a newly raised regiment was allowed to choose the facing colour, which at the time of the Red Coats was displayed on the collar, cuffs and lapels, as well as forming the ground of the Colonel's Regimental standard. It is believed that General Frederick "Boy" Browning, in accordance with this tradition, was given the honour of choosing a distinguishing colour for the newly raised Division he was to command. His choice of the maroon colour is believed to come from the colour he used for horse racing silks."7The beret was officially approved as the British paratroopers' new headdress and its authorization for issue is contained in Army Council Instruction 1596 of 29 July 1942.8

Canadian Airborne Berets: Dark Green or Maroon?

10 During the initial discussions concerning this new headdress, Lieutenant-Colonel G. F P. Bradbrooke, commanding officer of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion (1st Cdn Para. Bn), recommended that his unit be issued with dark green berets to match the backing of the parachute qualification jump wings.9 Three days later, 11 November 1942, Bradbrooke was informed by Lieutenant-Colonel J. G. K. Strathy of the office of the Director of Military Training (D.M.T.) that, during a meeting of the Military Members, it was decided that the Parachute Battalion should adopt the maroon beret. The Master General in charge of Ordnance (M.G.( ).) would take the necessary administrative procedures for procurement.10

Display large image of Figure 1

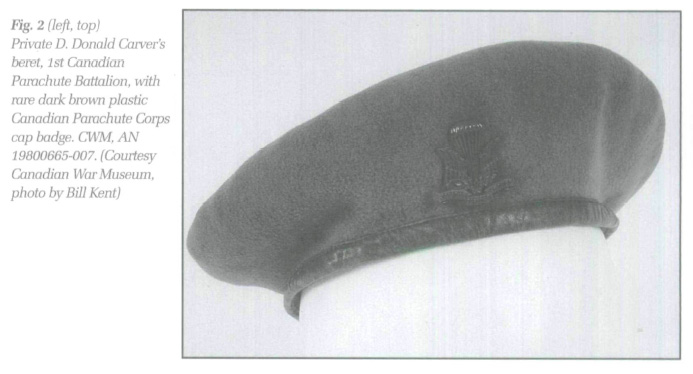

Display large image of Figure 111 On 16 November 1942, Colonel R. W. Keefler (D.M.T.) sent a memorandum to T.D.C.G.S. (B) (the Deputy Chief of the General Staff) recommending that they reconsider their decision concerning the adoption of the maroon beret. Keefler stated that the green beret would match the paratroopers' green buttons and background of the parachute badge. Brigadier Ernest G. Weeks returned the memo to Keefler with the following note, "... If we copy someone in the matter of uniforms it should be the British in preference to U.S.A."11 The matter was closed. Canadian paratroopers would wear the maroon beret.

Five Eras of Canadian Airborne History

12 The CWM's Airborne beret collection documents five different eras of Canadian Airborne history: the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, 1942-1945; the CANLOAN Program, 1943-1945; the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.) and Force 136, Asian Theatre, 1945; the Mobile Striking Force, 1949-1958; and the Canadian Airborne Regiment, 1968-1995.

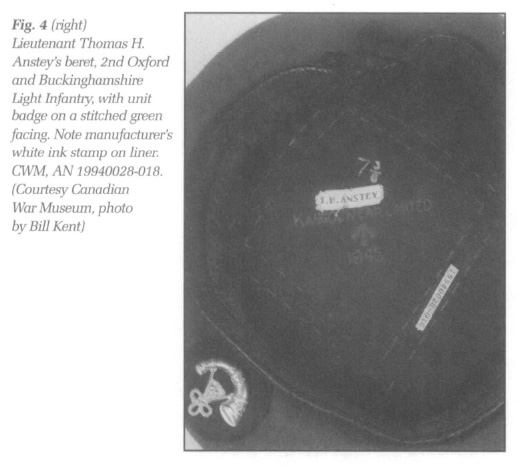

Manufacturing the First Maroon Berets in Canada

13 From December 1942 to March 1943, various sections and departments of the Canadian Army studied the feasibility of replacing the then-current Field Service Cap with the beret. The first Canadian Airborne maroon berets were manufactured by Dorothea Hats Limited of Toronto circa March - April 1943. The production run totalled 2 000 berets.12 The CWM does not have an example of this initial issue in its uniform collection. No Airborne berets were produced in Canada during 1944. In 1945, both Grand'Mère Knitting Mills, Montreal, and the renamed Dorothea Knitting Mills manufactured maroon berets.

Issuing the Maroon Beret to the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion

14 The first issue of Canadian Airborne maroon berets to members of the 1st Cdn Para. Bn took place in Winnipeg, in the morning of 26 April 1943, prior to the Fourth Victory Loan Parade. Ninety-nine paratroopers and four officers under the command of Major D. J. Wilkins were tasked to represent the battalion during the Fourth Victory Loan Parades in Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal.13 The rest of the battalion received their berets in Camp Shilo, Manitoba, between mid-May and early June 1943.

15 The issuing of each new item of clothing inevitably meant that a crash course was given on how to wear the item properly. Undoubtably, some paratroopers must have had fun experimenting or devising new ways of how the beret, in their opinion, should be worn. Others, who were overzealous, found out quickly that the new headdress was not meant to be pressed. Since none of the non-commissioned paratroopers had any experience wearing the beret, it was initially difficult to set an immediate dress standard for the paratroopers. On 12 June 1943, Lieutenant-Colonel Bradbrooke pulled in the reins and issued instructions regarding the proper manner of wearing the new headdress in Part 1 Orders #544, Dress — Wearing of Berets. "1. Worn with band level on the head, one inch above the eyes. 2. Pulled down to the right and slightly to the rear. 3. Badges worn 3/4 inch above the band and directly above left eye. 4. Under no circumstances will the beret be pressed."14

16 Throughout the war, the proper wearing of the beret was a constant cause of concern and frustration for the commanding officers of many units: the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion; the S-14 (later S-35) Canadian Parachute Training Centre, Camp Shilo, Manitoba; the 1st Canadian Parachute Training Company, Bulford, England; and those in the operational theatres. Listed in the Part 1 Orders of these units and the training centre were regular directives issued to the paratroopers on the proper manner of wearing the beret.

17 The Canadian maroon beret was used as a means of recognition during the Rhine Drop. During the preparatory phase of Operation "Varsity-Plunder," the Battalion received on 17 March 1945 Operation Orders, Copy #21. On page 6 of this nine-page document, listed under item #47 Recognition, is an interesting reference pertaining to the tactical use of the maroon beret. This headdress, due to its unique colour, would be a standby recognition measure during the first days of "Operation Varsity-Plunder." Because Airborne troops were dropped behind enemy lines, it was extremely important for the pilots to know the paratroopers' precise locations during aerial attacks and supply drops. To assist the pilots, each Canadian paratrooper was equipped with yellow celanese triangles. At unit levels they were equipped with fluorescent panels. The third and final entry for item #47, states, "RED berets will be worn only for minimum periods. If required or as urgent need for aid and recognition."15

18 In August 1945, at Niagara-on-the-Lake, the battalion's ranks were dwindling rapidly. The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion personnel were being demobilized. Most of the paratroopers retained their uniforms. The maroon beret became a prized possession, carrying with it powerful memories of the Battalion's distinguished role in Normandy, Dives, the Ardennes, the Rhine Drop and the North West campaign.

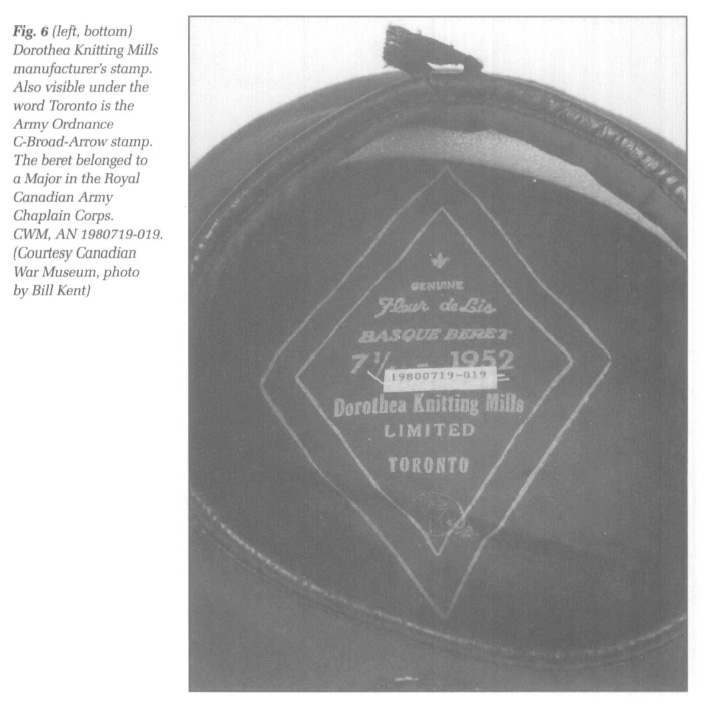

19 The CWM has two 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion berets. The first belonged to Private D. Donald Carver and is a British issue. The manufacturer's marking is faded and unreadable. However, another marking confirms that it was made in England, and the manufacturer was possibly Kangol Wear Limited, London, England. Stamped inside the liner is a white ink marking arranged in a diamond pattern: WDM 127 with an arrow pointed upwards. The stamp is located near the two ventilator holes. The letters W and D stand for War Department. This marking was stamped in the beret by Ordnance personnel following a quality control examination. It signified that the beret was now officially part of the British Army clothing inventory. This Airborne beret still has an original rare, dark brown plastic Canadian Parachute Corps cap badge (Fig. 2).

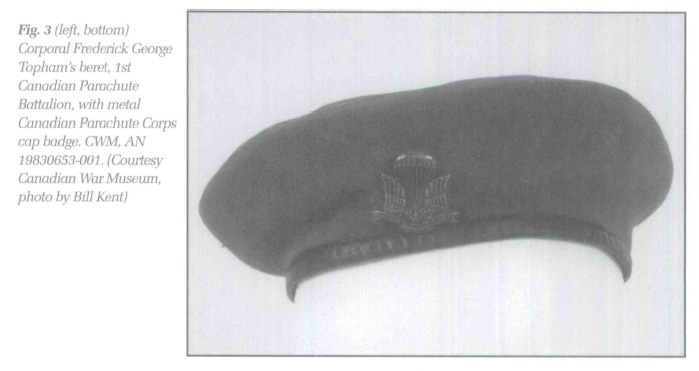

20 The second beret belonged to Cpl. Frederick George Topham, V.C., and has a metal Canadian Parachute Corps cap badge. This beret was a British issue, and was manufactured by Kangol Wear Limited. The beret's liner has a stamped white ink arrow marking, 7 W D 127, with an arrow pointing upwards. Also stamped are the manufacturer's name, beret size (7), and year of manufacture (1945). The CWM accession file states that Topham wore this beret after the Battle of the Rhine (Fig. 3).16

CANLOAN Program, 1943-1945

21 The CANLOAN program started in October 1943. During this period the British Army had a shortage of junior officers while Canada had a surplus. This program was developed to encourage Canadian officers to serve as volunteers with British Army units. The program's success exceeded all expectations. A total of 623 infantry and 50 ordnance officers volunteered. They "... became a distinct entity with distinctive CDN numbers, separate administrative arrangements, and an operational code word, CANLOAN."17 Of these, 100 Canadian officers served with various British Airborne units.18

22 The CWM has two CANLOAN Airborne officer's berets: Lieutenant Thomas H. Anstey's, who served with the 2nd Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry attached to the 6th Airborne Division, and Lieutenant George W. Comper's, who served with "C" Company of the 1st Border Regiment.19 It was agreed that the British Army would issue certain items of dress and equipment to the CANLOAN officers. Both berets were manufactured by Kangol Wear Limited. Comper's beret was part of the initial 1942 Airborne beret production run. Anstey's beret was manufactured in 1945 (Fig. 4).

Special Operations Executive and Force 136, 1945

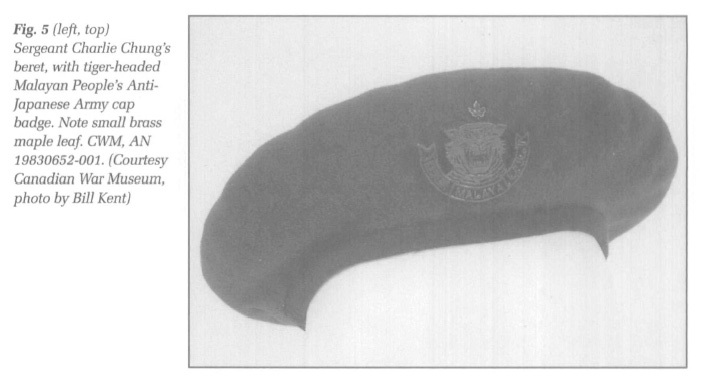

23 Another unique Airborne beret is the one that belonged to Sergeant Charlie Chung. He volunteered in early 1945 and served with two top-secret British organizations, Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.) and Force 136. During that period many Chinese Canadians operated deep behind Japanese lines in Burma, Sarawak and Malaya. Chung and seven other agents operated in the jungles of Kedah state.20 On his beret, Chung wore the tiger-headed cap badge of the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (M.P.AJ.A.) (Fig. 5). This beret was a private purchase from a civilian manufacturer and not a military issue item. Sewn on the inside liner by the manufacturer is a beige coloured label. Printed in black letters are the words "Regulation Pattern, G. A. Dunn and Co. Ltd., London and the Provinces." The beret is undated and does not list the head size. One interesting feature which distinguishes this beret from all the others in the CWM Airborne beret collection are the drawstrings protruding from the back of the cloth headband. One drawstring is black and the other is gold.

Display large image of Figure 2

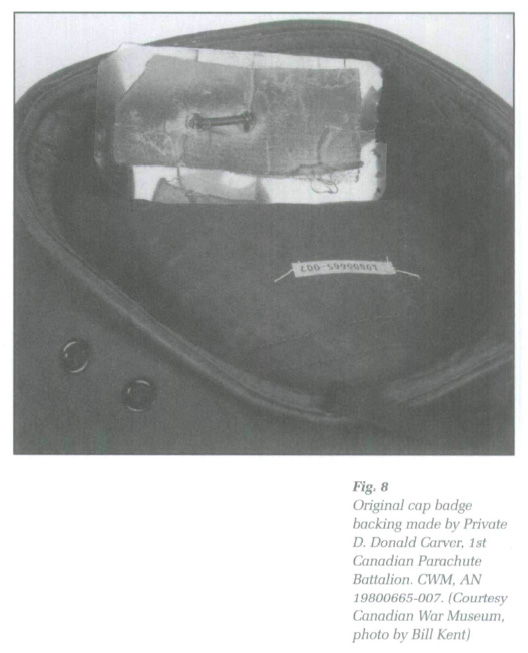

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 424 A second S.O.E. beret is currently on display in the CWM's "Hall of Honour" exhibit. The beret belonged to Captain Roger Marc Caza, a Canadian serving with the S.O.E. who was parachuted into occupied France and later in Malaya. His beret has a black leather headband, black drawstrings and the tiger-headed M.P.A.J.A. cap badge.21

Mobile Striking Force, 1949-1958

25 After the disbandment of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, the Special Air Service Company was formed in 1948 to carry out the parachute role within the Canadian army. After two years of training similar to that of the British Special Air Service Regiment, the Special Air Service Company was disbanded in 1949.22 The CWM does not have an example of the maroon berets worn by the members of this Company.

26 Shortly afterwards the Mobile Striking Force was set up. Its mandate was to defend Canada's northern border against Soviet attacks. The first Battalions of the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry, the Royal Canadian Regiment, and the Royal 22e Régiment (respectively P.P.C.L.I., R.C.R. and R22R) were given the Airborne designation.23 As training progressed each battalion was granted authority to wear the maroon beret: P.P.C.L.I. on 2 December 1949; R.C.R. in May 1950; and R22R on 7 August 1950.24 The CWM has twelve maroon berets that were manufactured during this period. The Dorothea Knitting Mills of Toronto produced these berets in 1952, 1954, 1955 and 1956. Three berets could not be dated. The markings in one of them were faded and unreadable. The liners in the other two berets had been removed.25

27 Five berets still have cap badges. The units documented are P.P.C.L.I. (with the King's Crown, see Fig. 1), the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, the Royal Canadian Artillery-Ubique badge with a red maroon cloth backing, the Royal Canadian Army Chaplain Corps with a dark blue cloth backing and the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery.26 The accession files of these five berets do not contain sufficient information to confirm whether in fact these badges reflected the donors' service with Airborne units of the Mobile Striking Force. It is impossible to determine whether they were issued later and document Airborne units operating during the Defence of Canada Force, 1958-1967 (also known as the Jump Companies era), or perhaps even issued during the early years of the Canadian Airborne Regiment in Edmonton 1968-1977.27 The accession files of two other berets confirm that they belonged to members of the R.C.R., and R.C.A. (Royal Canadian Artillery). They do not have cap badges. The remaining five berets do not have cap badges and the accession files contain no information as to the identity of the donors' Airborne units.

Canadian Airborne Regiment, 1968-1995

28 The Canadian Airborne Regiment (Cdn AB Regt) was activated 8 April 1968, and started training in Edmonton. Arrangements were made to start manufacturing new maroon berets as quickly as possible because the availability of this type of headdress was limited. The CWM has three berets documenting Cdn AB Regt. All three were manufactured by Dorothea Knitting Mills. One is dated 1972 and has no cap badge. The other two are dated 1974 and one has a Canadian Airborne Regiment cap badge (see Fig. 1, bottom beret). All three berets have built-in cap badge stiffeners and bear the manufacturer's white ink stamp. Other Airborne berets, from the late 1980s to the present, that were studied in private collections show that the white ink stamp was replaced with a printed, stitched-on label.28

The Beret as a Headdress

Physical Characteristics

29 The military-issue Airborne beret consists of five parts: the crown; the liner; the headband; the drawstrings and the ventilator holes. The crown is made of a dyed maroon wool; the liner consists of a black broadcloth type material; the leather headband is machine stitched to join the crown and the liner. Some production runs had a grosgrain cloth headband instead of the regular leather model. The drawstring was inserted in the leather headband and was left hanging out the two openings located at the back of the beret. This enabled each paratrooper to adjust his beret. Finally, two ventilation holes with black metal grommets are placed in the lower right underside of the crown and liner. Depending on the production runs, some grommets had a black leather backing, hand-stitched onto the liner. Manufactured cap badge stiffeners in the Canadian Airborne berets produced by the Dorothea Knitting Mills were introduced sometime during 1945. Later versions of the manufactured cap badge stiffeners varied, depending on the specifications submitted by the Army.

30 In the early years (1943-1946), Canadian manufacturers would stamp their markings in the liner using a turquoise-coloured ink. Later the manufacturers switched to white ink. The marking consisted of a double diamond. In it was listed the manufacturer's name, town and province, beret size and the year of production. Some also listed additional information as to the manufacturer's beret line. Example: "Genuine Fleur de Lis, Basque Beret" (Fig. 6). Upon reception of a shipment, the Army checked the berets and, if no problems were found, applied their marking, the C-Broad-Arrow stamp in white ink (see Fig. 6). The berets would then be officially part of the Canadian Army's clothing inventory. When numerous shipments of an item were received throughout the course of a year, as was the case with khaki berets, the stamp would also indicate the month.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

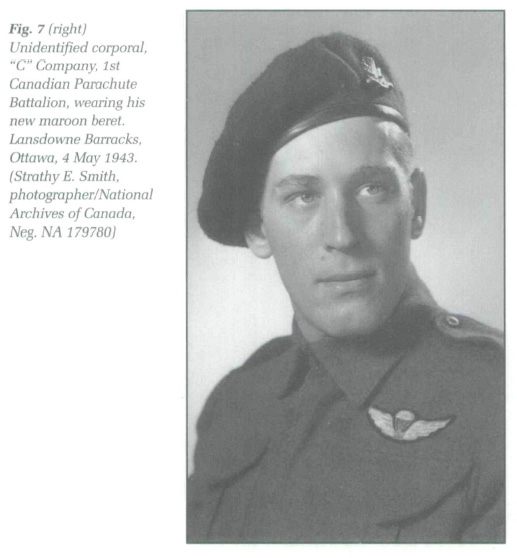

Display large image of Figure 731 Even before the manufacturing of the first Canadian Airborne berets, problems were anticipated regarding the dimensions of the crown of this headdress. During the 12 March 1943 proceedings of the Dress and Clothing Committee (Army Service), members were satisfied with a sample produced by a Canadian manufacturer. However, the Committee "... desires to point out the dimensions of the British sample should not be exceeded, when the Canadian manufacturer proceeds. The reason for drawing this to attention is, that in the case of Bonnets, Tarn O'Shanter and Caps Tank Battalion, there was a tendency of contractors to increase the size of the crown, with the result that there were complaints that the caps were too large; this should be avoided with the berets for Airborne troops."29 A series of black-and-white portrait photographs taken on 4 May 1943, in Lansdowne Barracks at Ottawa, show members of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion wearing their new berets.30 Note the size of the crown and the height of the shaft (the highest point of the beret starting from the headband) worn by an unidentified corporal, "C" Company, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion (Fig. 7). Also evident is the wool's fuzziness, indicating that this is a new beret. It was reported that the paratroopers used razors or razor blades to "shave off' the excess wool, thus giving their berets a smoother appearance. The corporal's Canadian Parachute Corps brown plastic cap badge is recessed in the folds of the shaft.

32 From the late 1940s to the present, paratroopers who were not satisfied with the crown's shape and size devised their own method to resolve this problem. The liner was cut out and the crown was soaked in hot water causing the wool to shrink. The water was then wrung out and the beret was placed and shaped on the paratrooper's head. It was then removed and left to dry.

Colour Designation

33 References to the beret's colour varied throughout the war. The most common designation used by British paratroopers was red. The German troops who fought against them during Operation Torch, 1942. in North Africa used the word rote, the German word for red. In other sources, the colour was described as cherry, claret, garnet or even burgundy. The official colour designation used in British and Canadian military records from 1942 to 1945 was maroon. A colour analysis of the CWM's Airborne beret collection revealed that there was a slight shading difference between the various Canadian Airborne berets. This shading variance was probably due to the manufacturers' preparations of different dye lots.

34 Once issued, the wear and tear, the sweat and the elements also had an effect on the beret's colour. A shading comparison of the CWM'S British and Canadian Airborne berets revealed that the British berets were slightly darker. Conversations with paratroopers of the Special Air Services Company, 1948-1949, the Mobile Striking Force, 1949-1958 and the Defence of Canada Force 1959-1967 revealed that in certain instances the paratroopers redyed their faded berets.

Berets: Durability of the Original Issue

35 Conversations with some 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion veterans and collectors confirmed that the lifespan of the original 1943 Canadian-issue berets was limited. Only two thousand were made. Some berets were lost during training or operational deployment, while others were reported stolen. Damaged berets were returned to the Company Quartermaster to be exchanged. Some veterans shared anecdotes revealing that sometimes berets were traded between Canadian and British paratroopers. Such was the fate of a large number of the original 1943-issue maroon berets.

36 When the battalion went to England in July 1943, it was agreed that the British Ordnance Corps would supply, upon request, Airborne berets to Canadian paratroopers. This is why numerous examples of 1944 and 1945 British Kangol berets are in the possession of collectors, museums and 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion veterans.

Modifications to Airborne Berets

37 Even though much effort and time had been invested in examining, testing and studying the quality control results of British and Canadian Airborne beret samples, Canadian paratroopers, the toughest critics, were not satisfied with the original issue. They proceeded to carry out their own modifications. A study of the CWM Airborne beret collection revealed that twelve berets showed signs of modifications. Two were authorized while the other ten document the paratroopers' unauthorized handiwork.

38 The two authorized modifications were noted in Carver's and Topham's berets. Inserted inside the left front part of Carver's beret is a piece of clear plastic, reinforced with tape. The Canadian Parachute Corps plastic cap badge's lugs were pierced through the beret's crown and liner, the plastic film and the tape. A plastic cotter pin, which was issued with this cap badge, secured it firmly in place (Fig. 8). This handmade backing was inserted to provide a solid backing enabling the badge to stand straight and be more visible. From the outset, the paratroopers of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion did not like their plastic cap badge. It broke easily and did not stand out against the beret's overpowering maroon colour.31 In Part 1 Orders 3 April 1943, Bradbrooke issued the following directive in the section entitled Dress, 5 Berets Item C, " A small piece of metal or cardboard should be fitted behind the badge inside the beret to ensure that it stands upright."32 A similar directive was issued later in Canada by Lieutenant-Colonel D. H. Taylor, commanding officer of the A-35 Canadian Parachute Training Centre, Shilo, Manitoba. "The background for the badge will be cut to the exact size of the badge and will be placed inside the beret."33

39 The second authorized modification was found on Topham's beret. It concerned the knotting and sewing of the drawstrings protruding from the leather headband, at the back of the beret. Bradbrooke issued two orders regarding the drawstrings. The first was issued 22 November 1943. He wrote, "The ends of the drawstrings on all berets will be sewn down to the band of the beret. There will be no loose ends left dangling." He reiterated this order on 3 April 1943 adding, "When the band fits properly, the tape at the back should be tied in a bow 1 inch in length. The bow should be then sewn to the band."34 Bradbrooke probably issued the first set of orders as a reaction to observations brought to his attention on the manner that the British paratroopers wore their berets.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 840 The other ten unauthorized modifications involved cutting off the drawstrings, removing manufactured badge stiffeners and replacing them with customized ones. Another beret showed signs of customization to the existing badge stiffener. The liners of two other berets had been removed. Capt. T. H. Anstey's beret had a white cloth label sewn to the liner. Printed in red ink, on the label, are his initials and name (Fig. 4).

41 Charlie Chung's beret is one of two berets that document modifications visible on the outside of the beret. A small brass-coloured maple leaf was placed over his tiger-headed Malaya cap badge. There are a few photographs showing Chung wearing his beret. The maple leaf does not appear on them. It is possible that this insignia was added after he left active service (Fig. 5). The second beret, a 1954 Dorothea Knitting Mills beret, features an intriguing modification to the headband. The original leather headband and drawstring were removed and replaced with a shiny plastic vinyl headband. This new headband was machine-stitched using a maroon-rust-coloured thread. This modified beret belonged to an unidentified member of the R.C.R. Regardless who did what to their berets, their wearers would always be recognized as a breed apart.

42 The CWM's Airborne beret collection is a silent reminder of our Canadian Airborne history and our paratroopers' accomplishments. The museum is always interested in examining Canadian and foreign manufactured Airborne berets, worn by Canadian paratroopers during active service, with a view to possible acquisition. A survey is currently being conducted to prepare a list of the beret manufacturers and years of production.

The author wishes to thank photographer Bill Kent for providing photographs to the CWM (Figures 1-6, 8); and Canadian War Museum staff: Cameron Pulsifer, Historian; Eric Fernberg, Chief, Armouries; Helen Holt, Dress and Regalia Collection; Liliane Reid-Lafleur, Information Assistant, Hartland Molson Library and Margo Weiss, Librarian Technician, Art/Photo Reproduction Services. Also thanks to National Archives of Canada staff: Dr George Bolotenko, Archivist and Guy Poulin, Assistant Archivist, Manuscript Division; Paul Marsden and Tim Cook, Archivists, Government Archives and Records Disposition Division; Peter Robertson, Photo Archivist, Visual and Sound Archives Division. To my colleagues, Airborne History specialists Ken Joyce of Ottawa and Malcolm Johnson of Brighton, Massachusetts.