Articles

The Historic Site as a Cultural Text:

A Geography of Heritage in Calgary, Alberta

Abstract

Historic sites serve their communities with an authorship of public memory at least as influential as more formal, written history. Drawing a distinction between museums and historic sites, where there is an attempt not only to reveal and represent history, but also to re-create place, this paper argues that the interpretation of history at such sites is frustrated by their structure and their attempts to animate the past, resulting in an aesthetic of "heritage." Focussing on two sites in Calgary, Heritage Park Historical Village and Fort Calgary Historic Park, I examine the ways in which history and heritage are constituted in this urban centre. Both sites operate within a cultural environment that values the concept of "heritage" over history. At these sites, history is told in a limited way, with an emphasis on practical uses in the present, particularly entertainment and profit. Moreover, in Calgary, the past is confined to particular spaces; such spatial fracturing of time serves to render the past irrelevant to the present-day economic and political development of the city.

Résumé

Pour une collectivité, un site historique constitue un ouvrage de mémoire publique ayant au moins autant d'influence que l'histoire écrite, plus officielle. Établissant une distinction entre les musées et les sites historiques, où l'on cherche non seulement à révéler et représenter l'histoire, mais aussi à recréer un lieu, l'article soutient que, sur ces sites, l'interprétation de l'histoire est contrecarrée par la structure et la tentative d'animer le passé, ce qui crée une esthétique du « patrimoine ». Se penchant sur deux sites historiques de Calgary, Heritage Park Historical Village et Fort Calgary Historic Park, l'auteur examine la façon dont l'histoire et le patrimoine se constituent dans un centre urbain. Les deux sites fonctionnent dans un environnement culturel qui favorise le « patrimoine » au détriment de l'histoire. Aux deux endroits, l'histoire tient une place limitée et l'accent est mis sur les considérations d'ordre pratique d'aujourd'hui, à savoir le divertissement et le profit. À Calgary, en outre, le passé est confiné à des espaces particuliers ; de telles fractures spatiales rendent le passé incohérent par rapport au développement économique et politique actuel de la ville.

1 Historic sites, as places where we may "visit" history, are central to a community's identity. Like written scholarship, the "authorship" of such sites, including decisions as to location and management, is integral to the final product and its meaning(s) to its intended and accidental audiences. Historic places reveal as much as written history about the cultural power to define, and may have an even greater ability to influence and construct, public memory. From monuments to museums, these preservations and commemorations reflect and participate in the production of memory and culture. Benedict Anderson identifies museums as one of three key "institutions of power" by which the nation is officially imagined.1 While such Canadian institutions remain understudied, there is now an extensive and critical academic literature on the politics of collection and display around the world, including civic and political aspects of their creation and use. There is, as well, in uhs writing an awareness of the space of the museum, from the way it contains historical artifacts in glass boxes, physically separating "history" from visitors, to the practice or ritual of the museum visit, with its prescribed routes of observation.2

2 The historic site that is an "open-air museum" or preserved/reconstructed building, however, distinguishes itself from the museum in that there is an attempt not only to reveal and represent history, but also to recreate or preserve place. As places, they bring new emphasis to the idea of visiting history that museums also advertise. At first glance, this might make a historic site more accessible. Instead, I will suggest that, in practice, visitors to these sites (residents of Calgary specifically) distance themselves from the history presented. Even as its reanimation enables the past to be re-performed in the present, the gap between them grows, rendering the past increasingly irrelevant. Nor is this ironic outcome entirely accidental. While it is not the intent of curators and administrators, the production of irrelevance is directly attributable to their actions. This situation is partly a reflection of a situation currently challenging all types of museums, the way in which "the liberal conception of culture has had to run alongside — if not compete with — neo-liberal notions of culture as a consumer product."3 Exacerbated as it is by the competitive context of consumer culture, much of the problem nevertheless is an issue intrinsic not just to the representation of an earlier time, but to the attempted re-creation and animation of the physical space of that time. The interactivity of such sites blurs distinctions between past and present, fiction and non-fiction, producing a spectacle where "modernist distinctions between real and the imaginary are no longer valid."4

3 Historic sites, even when they are theme parks, pride themselves as designated for the preservation of history and offer the visitor an enriched historical education. In such places the visitor is invited to go back in time, visit the past, and know what it felt like in "olden days." Instead of merely learning the facts and figures of historic events, guests at historic sites are able to gain a sense of the space, to appreciate its multidimensionality. Beyond its obvious three dimensions, there is also the opportunity to experience the sounds and smells, the movement of people, animals and other traffic. It is exciting to imagine the past might be "alive" again, an active instead of a static image. To place such activity on the stage of a site, where it can be "brought to life," defies the natural laws of time and provides the equivalent of foreign language immersion, where all the senses are brought into the learning of history. It is similar to the "interactivity" that is now commonly found in science museums5 whereby the visitor actively and intentionally becomes a part of the exhibit. Áine O'Brien has described this museum visitor as "not simply a spectator of a scene, but also a reader, an observer, and a walker who moves through the space of the exhibition (one who may at times even become an essential component in the workings of the display)."6

4 What interests me is the way specific spaces and the allocation thereof are used to preserve and also to restrict the history of a place — that is, the ways in which the act of defining is also confining, spatially and ideologically, the appropriate place and use of the past in a culture's self-perception, self-definition and self-identification. Space and the built landscape participate in the construction, or as Eric Hobsbawm might prefer, the "invention" of tradition. Tradition, in this approach, has much in common with Alberta's favoured concept of "heritage." While all history is narration that fills a therapeutic prescription for the teller and the audience, the emphasis on heritage or tradition is the most consciously selective of narratives. Drawing on work that has studied the production of culture in terms of history and tradition, particularly the institutional and spatial production of such culture, I investigate the production of this idea of heritage: where it came from, what it means, how it is used.

5 The "heritage industry" is now a well-studied phenomenon, particularly in the British example.7 There, the issue revolves more around the invention of a national image, with a focus on the role of the state in inventing the citizens' collective "heritage." While the industry is more developed in Britain than in North America, the well-debated distinction between history and heritage remains fruitful here. Broadly speaking, heritage is the aesthetic of history. Lacking both depth and specificity, it is history reduced to an economic and political commodity. The emphasis is on a sensory experience of the past, its exoticism and spectacle. The entertainment value of heritage sites is not merely their selling point, but increasingly their raison d'être and a principal influence in the selection of historical narratives recounted.

6 "Heritage" is, I believe, the current context of historic sites in Calgary. To illustrate this, I would like to present two specific sites: Heritage Park Historical Village and Fort Calgary. Through these two examples, I examine the ways in which history has been used and diffused in this urban centre. I think there are many positive and negative aspects to how these places "re-create" history, but I am not trying to provide simply a critique or review of these sites. Rather, through an exploration of the visitor's experience of these places, what the curators and administrators of these places have achieved and tried to achieve, and the context in which they make their decisions, I am attempting to raise questions about the role such places play in shaping our understanding of history and, ultimately, of ourselves.

Heritage Park Historical Village

7 Heritage Park Historical Village is the most popular historic site in Calgary. First opened in 1964 by the Heritage Park Society of the City of Calgary, this site houses more than 150 exhibits with over 45 000 artifacts on 66 acres of land in a suburban residential area southwest of the city centre. To handle the approximately 400 000 visitors the Park receives each year requires 55 year-round, full-time staff, 300 seasonal staff and 1500 volunteers. The park is open every day to the general public from the Victoria Day weekend through Labour Day, and continues on weekends only through Canadian Thanksgiving in October. From October to June, the park hosts school groups in a variety of programs, focussing on younger children from Early Childhood Education to grade 6. In addition to their historical programs, the site also runs a complementary catering and retail sales business. Groups are welcome to rent parts of the site for occasions such as office parties or weddings.8

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

8 Such a large operation is expensive to run and here is where the park nuis into an obstacle that helps shape, perhaps more than a curator might want, how the past is interpreted on the site. In 1996, Heritage Park cost about $6 million a year to operate. A little more than V6 of that budget came from an annual grant from the city ($1.1 to 1.6 million); some other financial support came from federal grants and from retail and ticket sales. To draw visitors, the park offers a free pancake breakfast beginning an hour before opening to visitors who have paid their admission. This meal is specifically promoted in much of the park's advertising and creates a further opportunity for the park to display its catering services. Many of the exhibits have created retail opportunities for the visitors as well. There are no fewer than twelve exhibits where one may purchase meals and snacks. The General Store is unabashedly a present-day establishment, selling park memorabilia and a wide variety of Western souvenirs.

9 Entrance fees and souvenirs, helpful as they are, do not generate sufficient income to maintain the site, and so, since the early 1990s, Heritage Park has employed a full-time, paid fundraising co-ordinator. One of the fundraising projects is "Partners In History." Through this program, the park receives funding from a business for a year for a specific exhibit: in return the business gets a small sign at that exhibit in recognition of its support. This initiative has been taken up mostly by oil companies, but also by private citizens.9 Because investors may choose to support a specific exhibit, some of the maintenance and development decisions are thus taken away from curators and their staff. As public funding gets tighter and dependence on private and corporate gifts increases, what places and times the Park is able to represent may be strongly influenced by "special interests" rather than a historian's interpretation of the past.

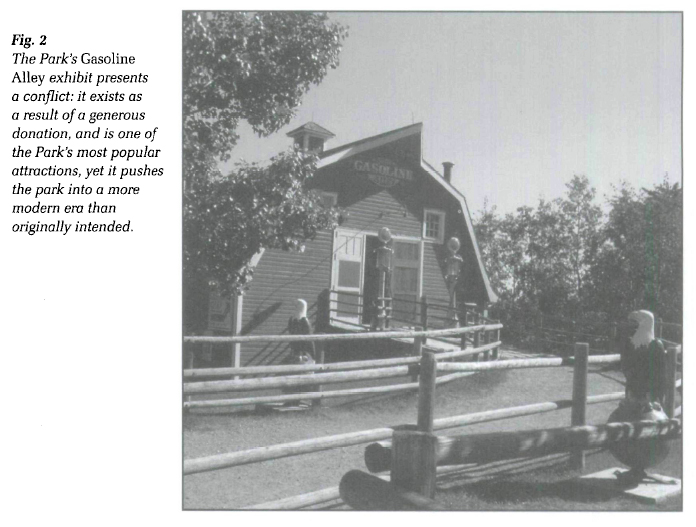

10 There have already been examples of conflict along these lines. The Park officially represents the time period 1880-1914. A new exhibit introduced in 1994 called Gasoline Alley, however, pushes the park into the automotive era, as far forward as the 1930s. The cars, gas pumps and other automobile memorabilia are from the collection of a local businessman and collector who offered them on loan to the Park. (The Park only accepted 1/3 of the collection, which includes artifacts from as late as the 1970s). The exhibit receives further sponsorship from Alberta Tourism and Shell Oil. Upon its introduction, Gasoline Alley immediately became one of the site's most popular attractions. Such generosity is a constant source of struggle for the Park. On average, Heritage Park receives three hundred offers of donations per year, eighty percent of which the administration turns down.10 Restricted funding not only signifies a possible decline in the curator's control over the site's current exhibitions, but also an increased reliance on donations rather than an acquisitions fund for purchase of artifacts needed for the development of new exhibits.

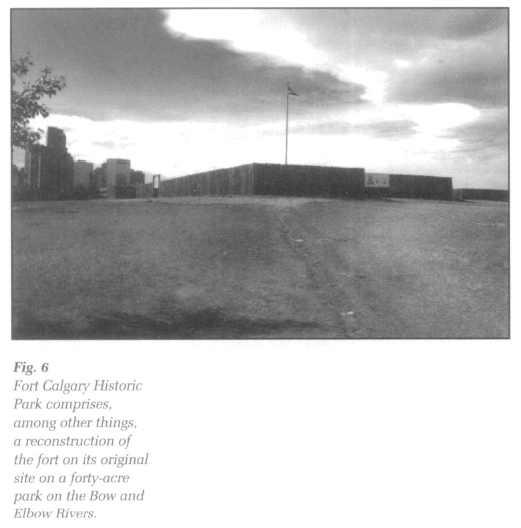

11 Gasoline Alley may be an extreme example of the disruption of the Park's mandate by donation, but it is not the first such occurrence. A large donation of carnival rides in 1984 created a permanent "midway" that adds a theme park atmosphere, not entirely desired by curatorial staff, to the town site. This exhibit, along with the train that circles the site and the paddleboat ride on the Glenmore Reservoir, collectively invent the possibility of an experience of the park that has nothing to do with history. Indeed, a survey done for the park in 1994 revealed that local residents, especially those with season family passes, occasionally employed the park only as a theme park, bringing their children to Heritage Park simply to play on the rides.

12 Ultimately what decides the issue of what to interpret, preserve, maintain or develop is another economic factor: attendance. Heritage Park has gone so far as to establish a Customer Advisory Council to assist the administration in assessing the interests of its visitors. This point, a sensitive one for museums of all kinds, raises a debate between popular culture and what is frequently called "elitist culture." Should short attention spans and the values of consumerism determine what aspects of the past we select to remember? Should we instead have dusty exhibits presented by dusty but educated curators, even if no one comes to see them? Museums in North America are all in one way or another walking a fine line between entertainment and education. Faced with dwindling state support, the pressure is increased, not just to be popular, but to even survive. Can authenticity be sacrificed to accessibility? What is the value of what remains? How accurate does the museum or historic site need to be?11

13 Accuracy is certainly an issue at Heritage Park. Much historical research underpins the efforts of curators to represent history in a way they feel is accurate. I believe their mission statement is sincere: "To entertain, inform and involve our guests in an atmosphere providing a heritage experience representative of pre-World War I Western Canada." Moreover, part of their operating philosophy includes a commitment to "respect the integrity of the period."12 There are nevertheless questions about the integrity of representation at any such site, as there are fundamental difficulties with both time and place. First, the site attempts to exhibit life over a period of decades as though many examples were contemporaneous. While it may be defensible to argue that the start of the First World War is a watershed time for the city, the thirty-five years preceding it were not without change. Furthermore, to re-create this historic place, the park has also relocated many of the artifacts and the buildings from places as far as Dundern, Saskatchewan, merging them as though they were collocated. In both cases, the representation lacks specificity, even when the objects are authentic, suggesting that the places and times within the West and its history are relatively interchangeable.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 314 The animation of the site, mostly through volunteers in period costume, is central to the visitors' experience. Many exhibits are staffed with at least one volunteer, who performs activities or duties appropriate to the time, location and character displayed. These individuals are thus part of the "past" — the exhibit itself — but also the present, as they interact with their audiences, answering questions and even initiating conversation. The presence of these particular workers serves to heighten the appearance of authenticity of this performance of history. First, they desire to increase and enrich the information available to visitors through their activities and answers. In a further way, their presence as volunteers testifies to an authenticity born of a pure love of knowledge. It is similar to the entrepreneurial "amateur enthusiast" who pursues preservation projects as observed in Israel by Ariella Azoulay. There, she argues, non-professional individuals and groups who donate their time and energy for the cause of history provide "a legitimating narrative for the supposed 'objectivity' of the representation of the past that the group produces since it is perceived as having sequestered the past from oblivion, saved the authentic from annihilation, and so forth."13 While the need to rescue history from such indifference is probably not felt as keenly in Calgary, the image of the volunteer, giving of her/his time and energy simply for the good of the community, does create an image of 'objectivity,' a superficial de-politicization of the interpretation presented there. How could there be any political motive, any bias served through the work of people with no obvious vested political interest?

15 The animation labour of the volunteers serves a further purpose. In addition to the relatively ad hoc performance and interaction with visitors, those in period costume also present sketches designed to illuminate various aspects of the exhibits. A skit I observed on a visit in 1996 illustrates the efforts of the park staff not only to bring the past to life, but to link the individual exhibits of the park and have them collectively seen as a single place. In the short drama, a man meets the train of a female relative (she having sat on the train among tourists) and brings her through parts of town while they have an emotional conversation that carefully mentions a number of aspects of turn-of-the-century social history. The joining of separate exhibits through the action and narrative of the skit intentionally establishes relationships between different spaces and discourages visitors from seeing them in isolation. Unlike the fragmentation possibly found in a museum among displays that are not related, the message of this skit is that Heritage Park is a single, coherent place.

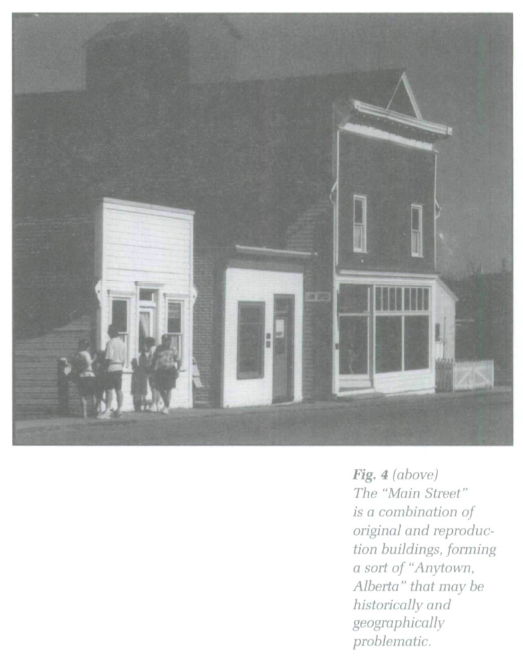

16 But what place is being represented here? The site itself is not of significance to the creation of a park there. The artifacts and reproductions are not specific to the site; many are not e v e n specific to Calgary. More profoundly, the spatial reconstruction of this site, even if it were anonymous, a kind of "Anytown, Alberta," is not historically accurate. In the town site area, the locations of individual buildings are not necessarily where they would have been in relation to each other in any small town in the West. They suggest exchanges and interactions that would not have taken place. The litter-free thoroughfare of Main Street is fronted by a combination of original and reproduction buildings from various locations, arranged to present a "typical," if selective, example of the kind of structures or businesses found on a Western street in 1910.

17 In particular, their chummy proximity serves to eliminate the appearance of racial and ethnic tension. Located around the corner from the Masonic Lodge and directly beside a law office, the Wing Chong Laundry is the only sign of a non-white community in the town.14 The exhibit is not animated; inside a visitor may read a more general account of Asian immigration to Canada, including the head taxes faced by the Chinese. But the placement of this laundry on the Main Street suggests peaceful coexistence, not segregation. It implies merely difference and thereby mutes a central identity conflict that shaped the development of Western Canadian cities, especially in Alberta and British Columbia.15

18 The re-created residential areas do not address such tensions either; the houses are beautiful examples of middle-class dwellings, and there are no examples of other dwellings in the "1910 Town Area." The closest we come is in the two teepee that stand a short walk from town, near the generic Hudson's Bay Company fort. These teepee are accompanied by the least amount of interpretation of any exhibit on the site; although Natives did erect teepee near Hudson's Bay Company properties, their location at Heritage Park with respect to the fort and the town is not intended to reflect anything specific. By the 1880s, all of southern Alberta (and Saskatchewan and Manitoba) had been turned over to the Canadian government by treaty, Native populations had been decimated by small pox and starvation, and had been settled onto reserves. Those that drifted into urban areas (usually requiring permission of the Indian Agent to leave the reserve) were greeted with suspicion and hostility. Calgary was no exception. In 1883, a reserve of approximately 260 square kilometres was created for the Tsuu T'ina (previously known as the Sarcee) near the western edge of the city. Although teepee continued to be used in some circumstances (such as camping during the Calgary Stampede) many residents on the reserve, including Chief Bull Head, lived in houses.16 The two teepee in the park do not express any of this history. Perhaps most revealingly, the skit mentioned above traversed the space of this exhibit, but without reference to the Native presence. The couple enters the field in conversation and continues as though the teepee were not there. This act of ignoring the exhibit and therefore erasing the Native presence is striking in a performance designed to express the coherence of the exhibits.

19 The use of space in both Heritage Park and Fort Calgary is integral to their meaning. The location and employment of these spaces contributes to the historical meaning of that space and the contemporary meaning. Before elaborating further on that, I would like to compare and contrast Fort Calgary with Heritage Park, then return with some concluding remarks on these sites and the broader issue of representation of time and space.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6Fort Calgary Historic Park

20 Fort Calgary's position is, in some ways, a mirror image of Heritage Park. Located a stone's throw east of the downtown business district, the site itself is of historical significance. It was here that the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) began the settlement that would become the city of Calgary, establishing a military outpost in 1875. Fort Calgary was part of a larger project to "tame" Western Canada and its Native population to better prepare the area for white settlement. Abandoned in 1914, today the reconstructed fort is part of a forty-acre park on the Bow and Elbow Rivers that includes an interpretive centre, the Hunt House Historic Site (related to the history of the Hudson's Bay Company), the Deane House Historic Site and Restaurant (originally the home of a NWMP superintendent), and walking paths. Remaining "true" to the inherent nature of this site, a minor military fort of the NWMP, limits the interpretation of history relevant to that site and those people.

21 In 1973, the city purchased the land where the fort had been located with the intention of developing a historic site. Existing buildings and train tracks had to be removed from the site and an archaeological survey was conducted to determine the precise location of the fort. An interpretive centre was built in 1977 and Fort Calgary opened as an organized historical park in 1978.17 For almost two decades, the fort itself was marked only by short posts and historical narration was mediated entirely through the interpretative centre. Its displays reflected the restrictions of a history narrowly conceived through the lens of a small fort. Displays concerned the life of the NWMP, their relationship with Native peoples in the area, and the image of the Mounties in Canadian and American popular culture. The relevance of such information to the history of Calgary was not explored, nor was there much interest in representing other populations besides these white, British-Canadian males. Women and immigrant groups were not represented here, and what there was of Native history was presented briefly and Eurocentrically.

22 Changes came with the reconstruction of the fort, which is ongoing. It now has a full perimeter and two stables and a wagon shed within; there are further plans for a blacksmith, carpenter, quartermaster's store and a hospital. Also, beginning in 1995, the interpretive centre underwent a complete overhaul and now stands as a small museum of Calgary history. Exhibits display the obvious military barracks, but extend to include displays relating to medicine, early journalism and transportation history. The museum offers several programs for school groups, including interactive archaeological activities that relate to the reconstruction of the fort itself. The plans of the Fort Calgary administration seem to follow the model of Heritage Park and many other museums and sites that have introduced more directly engaging interactive exhibits.

23 The future relationship between the reconstructed fort and the interpretive centre will be key to its identity. What Fort Calgary has gained in inclusive representation, it has lost as a physical historic site. The history of the fort itself has become increasingly marginal to the site's exhibits on the past. For now, rather than a historic site, where a place is re-created from an earlier time, the interpretive centre is a museum that could be located anywhere in the city. While the archaeological displays make a statement about the physical preservation of historic places, the interpretive centre contains the past within the walls of a museum. If Heritage Park is anything to go by, the reconstruction and animation of the fort will not necessarily link past and present in a coherent, relevant manner; it may, in practice, serve to sever any connection.

24 At every turn, there is the opportunity to divorce the past from the present. When the past is treated as "a simple existent...there both to be dug up and also to be visited,"18 any sense of a dynamic relationship with the present is impossible. The archaeological aspect of Fort Calgary presents a similar veneer of unbiased authenticity that the volunteers do at Heritage Park: history is not constructed; the past, as represented by this structure, lies waiting to be uncovered.19 But its presentation of the rime of the past as a place to be visited is the central point of distancing the past from the present. The preservation or reconstruction of an actual site, such as Fort Calgary, or the invention of a "typical" historic locale, such as Heritage Park, involves a re-creation of place that is not fully realizable. And it is within the interactivity of the animated site that past and present are further blurred until no distinction is possible or desired. No relationship between past and present is established, and a severing of the two, like that achieved through spatial segregation, is facilitated.

25 The participatory, multisensory experience emphasizes an aesthetic experience, rather than encouraging a reflective, deeper knowledge. This performance of history, however, appears no less authentic or authoritative than a display in a museum; there would be no reason to believe the actors were "making it up." Indeed, the volunteers, their period costumes and their activities imply that history is being shown simply as it was, with less of the mediating interpretation of a curator than in a museum. By this implication, the interpretation is in fact more controlled than in the museum's glass boxes: by immersing visitors in the display itself, the site complicates, and possibly eliminates, their ability to achieve the necessary arm's length for doubt or debate. The aesthetic is thus more easily accepted as a true telling of the past, easily silencing questions that are never asked. Having "lived" the past through the experience of their own bodies, visitors do not suspect mat they have missed anything.

26 Other than these two large sites, there are few other places of recognized historical significance in Calgary, and certainly none more popular. In a small part of the downtown, the Stephen Avenue Mall, several buildings have been preserved from the city's early days; it, too, is principally a tourist destination. Allocating a few areas — with substantial acreage — to the preservation of history enabled the city to preserve little else in other areas, particularly during the peak construction years of the oil boom. It is as though these designated spaces are to do all of the memory work for the city, legitimating the reinvention of the rest. That actual buildings were removed to the space of Heritage Park reinforces the notion that the historic site is the appropriate location for historic objects, not the lived spaces of everyday life.20

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 727 The more contained and defined the space given to history is, the less relevant that history becomes to us. It is not meaningful in and of itself to preserve old things. Perhaps it would be valuable here to underscore the difference between old buildings or other artifacts of earlier times and history. "Old things" are not history. History is the context and meaning we impose upon such objects from the past. When little or nothing is done to contextualize those objects, to emphasize their relevance and the relevance of the past to the present, then they do not create any but a superficial sense of historic value. If we place the objects in irrelevant contexts, their meaning is confused. If we contextualize them in an inaccurate but therapeutic way, then our subsequent "history" is self-delusional therapy, not education or enlightenment. Without the weight of historical interpretation, objects of the past are unable to apply any pressure to the present. Certainly if the past does not mean anything to us, it is not part of our identity; in that case, we do not express ourselves through our study of history and it will not reflect what we consider to be our realities. The malleability, flexibility and irrelevance of "heritage" make it more desirable and more consumable than history. As the curator at Heritage Park put it, heritage is a less formal term, a "softer word" that is commonly used by the Conservative government of Premier Ralph Klein.21 History, in contrast, carries more baggage.

28 What has resulted from a heritage approach to history is that visiting a historic site in Calgary is ultimately an exercise in tourism — not only because the site is entertaining, but because the past is represented in such a way that visitors are involved but not personally implicated. As tourists to this place — a place that purports also to be a time — they may extricate themselves at the end of the walkabout with no consequences. They are not compelled to take with them any inheritance of the past, any understanding of how their lives are a product of it. Tourists are thus welcome to see the past to be as insignificant as a fantasy park. Such a representation is presentist in the extreme; the past is cast as an exotic irrelevance. Moreover, this tourist gaze assists in turning the past to economic purposes. The more attractive and consumable the past becomes, the more easily one can sell t-shirts and other tokens that commemorate not the past but the present visit. The more successful such commercial aspects are, the more easily the retail and entertainment aspects of historic sites may become more dominant features of their landscapes, both in the spaces of the shops and rides, and in the spaces of the exhibits themselves.

29 The idea of heritage has permeated the representations of past and present in the West, particularly but not exclusively in Alberta. As Lowenthal has observed, "The past is always altered for motives that reflect present needs. We reshape our heritage to make it attractive in modern terms..."22 History, especially in its public, spatial forms, has become driven by consumerism, tourism and a flight from the ugliness of the past. This has played its part in the construction of an urban culture that lives exclusively in the ultra-modern present, mindlessly embraces economic and political power, fears and avoids conflict, and prizes simplicity and homogeneity over the messiness of diversity and complexity.

30 But the heritage/history debate constituted by Fort Calgary and Heritage Park is exacerbated by the specific history of the development of the city of Calgary. The present urban centre, whose political and economic landscape now has national significance, is the product of the post-Second World War oil boom. Regardless of the pre-1914 focus of both sites, and the non-date-specific but certainly pre-urban image of the cowboy of Calgary's Stampede, the history of the existing city's social, political and economic geography is, at most, forty years old. Furthermore, much of it is imported, with no roots in the area. Not only is the city dominated by new and different industries, they were built with large influxes of capital and population from other places (mostly central Canada and the United States). In 1981, the time of the first crash of the oil boom and the slowing of its accompanied population growth, almost forty percent of Calgary's residents were Canadians born in other provinces; a further 21 percent of the residents were foreign-born. Even today, more than 50 percent of the city's population comes from outside Alberta; 20 percent were born outside Canada, and 33 percent are people born in Canada who have migrated from other provinces.23 On the surface, it is more a coincidence than the product of coherent, contiguous chains of historical events that present-day Calgary happens to be in the same place and have the same name as the place commemorated by its historic sites. The city has created historic, even romantic, images of itself to which its citizens have little experiential or ancestral connection, but which satisfy emotional and aesthetic needs for authenticity and depth.

31 Perhaps it is not in the general interest of elites or other citizens to integrate this history in anything but a superficial, aesthetic way into the city's identity. Neither the ideological nor the spatial segregation of history from the present would suggest cause for concern. The blur of fact and fiction, past and present, actual and invented merely adds to the entertaining spectacle that tourists enjoy, and assists these sites in becoming financially successful and thus sustainable. The physical and emotional distance from these sites and their containment in a generous allocation of separate space facilitates the production of their irrelevance. By reaching farther back in time than the years of the oil boom, they create a sense of depth in Calgary's history, but its interpretation as heritage allows this to happen without addressing the challenges of its complexity. Nostalgic sentiments are fulfilled by being seen to remember, rather than remembering and living the consequences of such memory.

32 In addition to broader cultural implications, what might we wonder about the political agenda inherent in such a containment of history? In his review of a New York exhibit on Irish Immigration, Allen Feldman succinctly states, "The construction of public memory is an eminently political act..." and bids us to "understand the museum exhibit not as a passive reflection of culture and memory but as the creation of culture and memory..."24 Does confining history not free us from the difficulties that the past may impinge on contemporary politics? By suggesting that the past as "heritage" is that flexible, are we not also suggesting that the future, too, is flexible? While certainly historians are somewhat free to see the past as they choose, this idea of "heritage" smoothes the path to a place where the past is irrelevant. Its containment in certain places suggests an even greater freedom in other, "history-free zones." In such zones, the past is not allowed to interfere with the smooth running of politics and economics. In these spaces, we may remake ourselves, unfettered by roots and rust.

33 The problems of representation at the historic site, where an attempt is made to re-create place, frustrate curatorial desires for clarity, depth and authenticity. In the context of consumer culture and dwindling financial resources, the project is further diverted by the need to survive. An increasing orientation towards the consumer (rather than the student or citizen) means entertainment complements education, and often competes with it. History is re-presented as heritage; the past is reduced to another tourist commodity. With the resulting divide of past and present or a blurring of distinctions between them, or both, historic sites achieve little in linking the two meaningfully. Moreover, in a city such as Calgary, with its less obviously related layers of history, forging such chains would be a daunting task. At a minimum, museums and historic sites need the assistance of a strong system of formal education in history, and curators need the support — especially financial support — of politicians and citizens to pursue freely a rigorous interpretation of history that goes below the surface.

I would like to acknowledge and thank Sylvia Harnden, curator at Heritage Park Historical Village, and Margaret Ann Knowles, curator at Fort Calgary Historic Park, for their generous assistance with this research. I also thank my research assistants, Dr Sarah Payne and Dave Rossiter. Finally, I express my gratitude to Doug Parker and an anonymous reviewer for reading and commenting on earlier drafts of this paper.