Articles

Time Balls:

Marking Modem Times in Urban America, 1877-1922

Abstract

This article describes time balls, a long forgotten technology for marking the time. It focusses on the period between 1877 and 1922, when several dozen time balls were erected around the United States and many more were requested. Additionally, the essay provides a history of time balls in the United States from their first appearance in 1845 to the final drop of one in 1936. It argues that time balls were primarily monuments to modernity, rather than navigational devices or instruments for public dissemination of the correct time.

Résumé

Cet article décrit les ballons horaires, une technologie depuis longtemps oubliée qui a jadis servi à marquer l'heure. Il y est surtout question de la période de 1877 à 1922, alors que plusieurs dizaines de ballons horaires ont été installés aux États-Unis et que l'on en réclamait davantage. L'article présente aussi l'histoire des ballons horaires aux États-Unis, de leur apparition en 1845 à la chute du dernier en 1936. On y explique que les ballons horaires étaient principalement des monuments à la modernité, plutôt que des instruments de navigation ou des mécanismes permettant de donner l'heure juste au public.

United States Naval Observatory

dated August, 1884

1 During the decades after the Civil War time balls joined the array of newly erected monuments across the nation, many of which embodied the cultural, commercial, and political aspirations of Americans. Typically perched atop the highest point in the central part of a city, usually a tower, these globes with metal ribs and canvas covers of various colours were rigged to an electric pulse, which caused them to drop at noon. The daily, except Sunday in most cases, dropping of the ball was a public event, and on occasion of error or failure to drop, notice was published in city papers. First built in England in 1829, arriving in the United States in the 1840s, but only proliferating in the 1880s and 1890s under the aegis of the United States Navy, time balls could easily be understood as one of the more minor, though intriguing, devices designed to disseminate time.1 This article, however, seeks to call attention to time balls as symbols of civic modernity, arguing that their vogue arose out of their ability to indicate modern times, rather than the correct time.

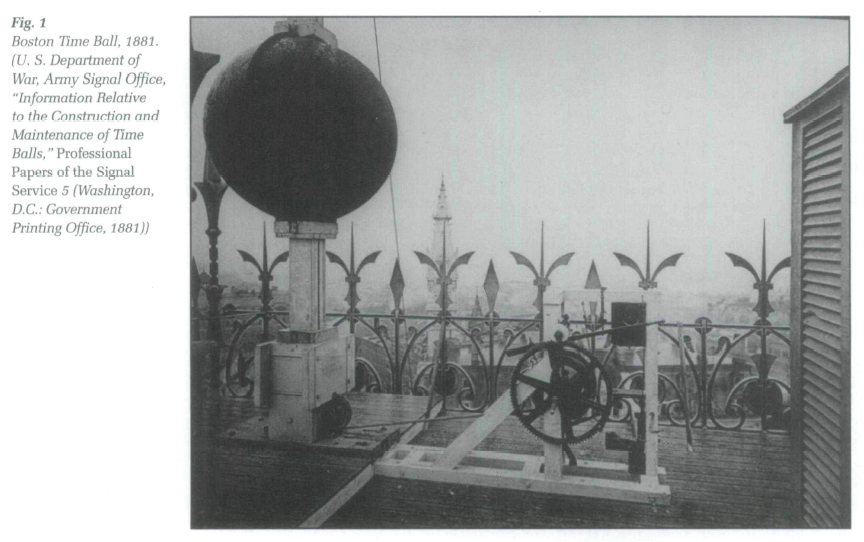

2 This essay focusses on the years between 1877, when the nation's most prominent time ball first dropped, and 1922, when almost all time balls were decommissioned and requests for time balls ceased. This period coincides with the emergence of the historical period denoted by the term "modernity" and the rise of the artistic movement now known as "modernism." Theorists have imputed to modernity a "new consciousness, a fresh condition of the human mind," and have located its origins in the cataclysmic economic and technological changes of the late nineteenth century. Literary critic Northrop Frye observed that these events fostered "a type of consciousness frequent in the modern world," one that was "obsessed by a compulsion to keep up." Modernity also created "an awareness of contingency as a disaster in the world of time," and spread "a sense of disorientation and nightmare." Modernist literature and painting share a sense of urgency, which could be described as an orientation to the "now."2 As modernity and modernism took shape, contemporaries identified the strong sense of contingency that permeated European and North American cities; the "vast agglomerations of people in widely contrasted roles and situations" made cities into "places of friction, change and new consciousness."3 Time balls at once reflected and reinforced this new consciousness. Dropping only once a day, and otherwise standing as mute symbols of the time, they monumentalized the now, the present, the instant (Fig. 1).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 The first time balls were dropped in Portsmouth, England, in 1829 and Greenwich in 1833 as maritime experiments. Knowing the correct time enabled the determination of longitude, which was central to efficient and safe navigation. But chronometers varied in their going-rate (how fast or slow they ran from day to day), and when in port captains were responsible for rating their timepieces, so that when at sea they could make the necessary corrections and thereby chart their course with certitude.4 Other means of publicly disseminating the correct time included firing guns, on the presumption that both the report and the gun smoke would alert interested parties as to the time.5 By 1844 the world's eleven time balls had developed into devices meant to aid ship captains and navigators in the deadly serious task of rating chronometers.

4 Shortly after moving into its first building on a bluff above the Potomac in 1845, officers at the United States Naval Observatory attached a large sphere to the flagstaff, and at the precise instant of noon (Washington, D.C., mean solar time) the ball was "thrown down by hand." The signal prompting the drop was either orally delivered or "made by hand from an assistant stationed in front of a mean time clock in the Observatory." After the ball was released it landed on the Observatory's dome, and then rolled to the roof beneath, only to be hoisted up to the top of the pole the next day.6 It was clearly almost useless to navigators, few of whom would have bothered to anchor so far inland along the Potomac. Perhaps not intentionally, but almost certainly in practice, the naval observatory's time ball fulfilled the same function as did monuments: it defined a public sphere of citizens, those in Georgetown and Washington, who could observe its descent. But rather than glorify a past moment, the time ball heralded the present.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 25 A year previous to the time ball's appearance in the nation's capitol, the introduction of telegraphy made possible the dissemination of accurate time (as determined in astronomical observatories through a variety of means). However, being able to telegraph time signals was not sufficient; some manner of publicly indicating the time once it was transmitted was necessary.7 After mid century, daily time signals from either a master clock or an observatory were sent to newly established municipal fire alarm systems, and so city and church bells would ring at noon, providing an aural time signal.8 Railroads also utilized the telegraph's capacity for time dissemination. Before telegraphy they designated a master clock along their routes. Train conductors would set their watch by this clock and carry the time to other depots. The extension of telegraph wires enabled the immediate and rapid transmission of time signals to railroad depots. Once a clerk received the time signal, he was expected to manually reset the straying hands of the clock. By the middle decades of the century, the time on the local railway depot's clock came to serve as the standard in most places. Depots with more than one railroad passing through tended to have more than one clock showing more than one time, such as the depot in Kansas City, Missouri, with its five railroad times and as many clocks.9 Watch and clock makers in larger port cities were eager for telegraphic connection with observatories for their trade depended in large part on navigators, who insisted on having accurate chronometers. In many cases their proprietors were also officially recognized as municipal timekeepers. Clocks, and in two known instances a miniature time ball, prominently displayed in shop windows made the correct time visible to pedestrians.10 With the development of automatic means of regulating and resetting clock hands between the 1860s and 1880s, culminating with the success of the "Self-Winding Clock Company" in the 1890s, the problem of disseminating the correct time was solved.11 Wireless transmission of time signals was the icing on the cake.

6 During the time when methods of time dissemination were maturing, few time balls were proposed or built in the United States, in large part because they were considered impractical. For instance, around mid century a prominent Boston chronometer maker pointed out that were a time ball placed on the cupola of the State House, only a small number of city inhabitants would see the ball drop. Furthermore, most navigators in port, if they could see the ball, could little "afford time to prepare and watch for the signal."12 Consequently, the only two time balls erected between 1845 and 1860 were both on San Francisco's Telegraph Hill in 1852, each of which was a short-lived commercial venture.13 During the 1860s four time balls were erected, all at the insistence of regional observatories seeking to highlight their ability to deliver accurate time.14 But in the early 1870s officers of the United States Naval Observatory began to lobby for the erection of time balls in prominent places such as New York City's central business district and the Government Building at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.15 It was not until 1877 that a time ball that might rival Washington's 1845, and still operational, device was erected, and this initiated not only a period of technological improvements for time balls, but also their emergence as monuments to modern times.

7 In 1877, the Western Union Telegraph Company garnered tremendous publicity when it erected a time ball on top of its New York City headquarters, and announced that daily, except Sundays, the ball would drop precisely at noon. A seeming wonder of modern technology, the Western Union time ball was connected through the wires to the clocks, transit telescopes, and scientific expertise housed in the nation's premiere observatory, that of the U.S. Navy.16 When in 1885 the naval observatory's time ball was relocated to the State, War, and Navy Department Building (which was no accident of location, but a deliberate choice meant to communicate the nation's veneration of accurate time), the system for releasing the ball relied on the telegraph and electrical circuitry and thus appeared to be considerably more sophisticated than the earlier one, where the signal was gestural or oral and the ball manually released.17 By this time large clock-dials, electrically controlled or synchronized systems of "master" and "slave" clocks in multi-office buildings and factories, and church and fire-alarm bells also announced the time to the public.18

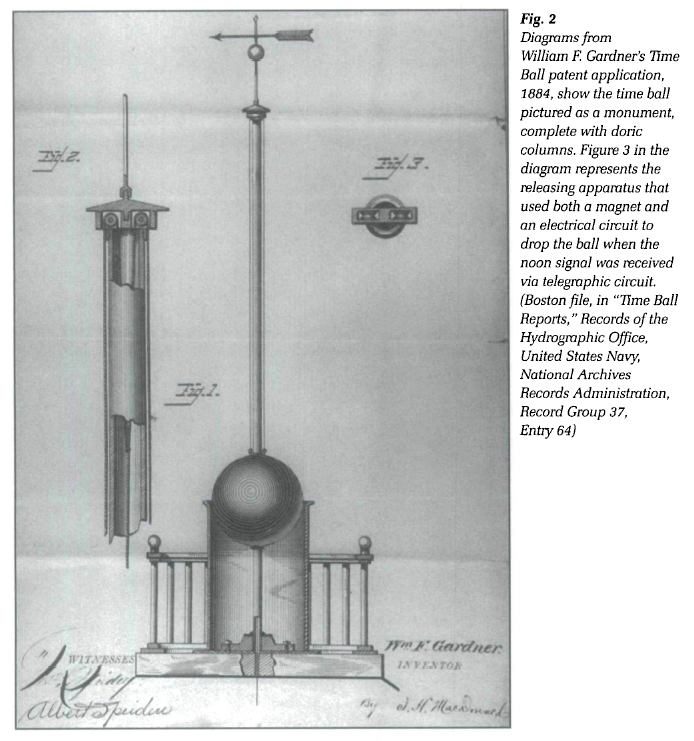

8 Just when other technologies for transmitting the time had developed sufficiently to ensure their feasibility and reliability, interest in time balls heightened. Between the first drop of Western Union's time ball (1877) and that of the new Washington one (1885), the leading instrument-maker for the United States Naval Observatory, William F. Gardner, perfected the mechanism for releasing the ball when the telegraphic time signal was received, which was acknowledged as "the essential part of the apparatus."19 At its most basic, the ball, with a diameter between two and four feet, was constructed out of a framework of wood, steel or iron and covered with canvas usually either black or red, and weighted sufficiently so that it would drop instantly fifteen to twenty-five feet.20 Shortly before noon, the ball would be raised, usually by hand, up a staff secured to the top of a building or tower. A few seconds before noon, the releasing apparatus (which utilized a magnet and electrical circuits) was applied, and if all went well an automatic signal would then release the ball21 (Fig. 2). With such a set-up it is easy to understand how things could go awry: wind or ice could prevent the ball from being hoisted, trouble with the wires could interfere with the signal, the releasing apparatus could be triggered accidentally.22 More than one officer in charge of time balls made it his "custom to drop the ball by hand," surely not a reliable way to transmit "accurate time."23 When the ball was released at the wrong time, most relied immediately on braking systems to "arrest the ball in its descent," and later on the local press to notify the public that the ball was dropped in error.24

9 With only the most elementary understanding of the technology, one must wonder how much time balls assisted in the rating of chronometers. The active trade in chronometers in several leading American ports suggests that ship captains frequently rented chronometers (which usually were rated) for their voyages, and paid agents to rate their chronometers while they were in ports of call. To rate chronometers, watch and clock makers, such as William Bond & Son of Boston, received time signals in their shops, either via Western Union's time service or over dedicated lines from local observatories.25 As one 1859 circular promised, William Bond & Son "will loan chronometers for long and short voyages," and the business's daybooks show that it made good on the promise. Early in 1852 their business was active enough that they called in a lawyer to determine whether or not they were liable for chronometers left "in our charge for rating and repairing."26 A catalogue of timepieces to be sold in a public auction in 1876 included the entry: "Lot 5:45 Second-hand chronometers of various makers. These chronometers are at sea, loaned out."27 In 1885 when branches of the Navy's Hydrographic Office began to offer free rating of chronometers in its offices, Bond & Son and other chronometer merchants were outraged, for rating chronometers was a chief part of their business.28

10 Additionally, evidence gathered by the United States Hydrographic Offices in various ports reinforces this view that few ship captains relied on time balls to rate their chronometers. For instance, the officer in charge of Boston's Hydrographic Office found in 1886 that a prominent member of the Chamber of Commerce had never heard of the time ball, and those city officials who were "in the know" did not make use of it, since "bells are struck all over the city at noon by the Cambridge Observatory." He further reported that "prominent shipping people" assured him "that the ball is seldom if ever made use of by the captains of vessels for rating chronometers." Captains of ships themselves confirmed this report, stating "that they seldom see the ball, and never think of rating their chronometers by it."29

11 Furthermore, the process of using a time ball to rate a chronometer should be considered. Even if the time signal was transmitted without interruptions on the line, if the ball was hoisted without problem, if the battery, electrical circuitry, and magnets were working correctly, and the wind not blowing too terribly hard, so that the ball, therefore, floated down the pole at precisely noon of some known meridian, how would the officer in charge of rating the chronometer have been able to note the time ball's precise moment of release and exactly where the hands were on his chronometer, which usually would have been kept in a protected place? Even if an assistant rang a bell or hollered once the ball began its descent, would such an aural signal have been reliable enough to navigate ships with millions of dollars of goods, not to mention countless sailors, officers and passengers on board? If time balls were used to rate chronometers in any significant manner, which I doubt, they must be understood not simply as visual time signals, but as parts of networks of associated signals. More evidence is necessary before it can be proven, but it is plausible to argue, as I am doing here, that time balls were irregularly used to rate chronometers used in navigation.

12 If it was the case that time balls were impractical, then why did branches of the United States Navy devote significant energies and funds to the construction, maintenance, and operation of time balls after 1884? The answer lies in the monumental nature of the devices, for they were able to signal the presence of the United States Navy in ports where commissioned American ships were only infrequently sighted since the War of 1812.30 True, some people set their watches and clocks by the time ball, as did the stagehand at Ford's Theatre the day Lincoln was assassinated.31 The Boston Hydrographic Officer quoted above concerning the disregard of the time ball in 1886, concluded his comments with the observation that the ball was "of use to hundreds of people who regulate their watches by it, and in all probability there would be much complaint were it removed."32 The Naval Observatory and the Hydrographic Office, the two departments of the Navy that oversaw the construction, maintenance, and operation of time balls, did not purposefully engage in monument building. Their missions did not stipulate such activity; but in practice, the devices served little other than symbolic purposes. Time balls played a minor role in navigation, and a somewhat more pronounced part in the public dissemination of time. But naval officers, commercial elites, and local politicians supported their erection with a passion that does not match the device's limited utility. Time balls derived the critical portion of their desirability in the realm of the symbolic.

13 Western Union's New York City Time Ball heralded the short golden age of the time ball in American cities. In the spring of 1878 a Boston clock maker's daybook noted "The time ball on top of the building of the Equitable Life Insurance Co. corner of Milk and Devonshire St. was dropped for the first time today." Harvard College's Observatory sent the time signal gratis, the United States Army's Signal Service operated the mechanism each day, and Equitable Life Insurance paid for the apparatus.33 Between the Boston ball's drop and 1883, eight time balls were established in cities as far west as Crete, Nebraska, as far north as St Paul, Minnesota, and as far east as New Haven and Hartford, Connecticut.34 The most modern of enterprises in 1880, the Connecticut Telephone Company, paid to have a time ball dropped on the roof of its Hartford offices each day, perhaps already acknowledging the telephone's pivotal role in transforming practices associated with time co-ordination and synchronization.35 Civic leaders hoped that the time ball standing 140 feet above street level in Kansas City, Missouri, which an appropriation from the city council paid for, would "be a prompter of punctuality."36 Clearly the time ball was a harbinger of modernity, a tribute to instantaneousness and accuracy, an indication of the eagerness to memorialize forward-thinking.

14 Time balls were among the first material representations of the federal government outside of the District of Columbia. They sprouted up in cities during the same decades that soldiers' homes were spreading across the nation, monuments to American presidents were being dedicated, and federal courthouses were being built in each federal jurisdiction. By 1884 the Navy had secured its long-held right to erect and operate time balls, overcoming a legislative challenge posed by the Army's Signal Service. As it became obvious that uniform and correct time would have to be disseminated across the nation for the worthwhile comparison of geophysical observations, the Signal Service became more and more frustrated with the piecemeal, haphazard manner of time-keeping. So it proposed to erect time balls at fifty-five of its signal service stations (including ones in Bismark, Dakota Territory; Leavenworth, Texas; and Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory) and to cooperate in the maintenance of "public Standard Time Balls" elsewhere. The Navy presented its own plan, which involved placing time balls on the custom houses at ports of entry and in other cities of more than fifteen-thousand residents. Neither of these plans received the kind of political support necessary, most likely since appropriations would have had to amount to more than $25 000 during a time when the federal budget covered little more than military pensions, and these only for veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic.37

15 So, by 1884, when the prominent time balls in New York City, Boston, and Washington, D.C, and those in upstart places like Kansas City and Crete, Nebraska, dropped, they denoted both dominance and aspiration in scientific, financial, and cultural arenas. They also signalled willingness to lead Americans into disposing of local time in favour of the standard time of time zones, an innovation that railroads had introduced on Sunday, 18 November 1883. Time balls signified connection to accurate and standard time, and represented the knitting together of a nation previously living as if on islands of local time, based on a multitude of meridians, rather than only that of the 75th, 90th, 105th, and 120th. City boosters sought time balls of their own as part of their larger quest for status. However, the prohibitive expense of the equipment and of the telegraphic connections to a reliable source of time prevented most from erecting their very own monuments to modernity.38

16 The desire of some places to adorn their newly developing skylines (for it was in this period that skyscrapers made their debut) with symbols of accurate time coincided with the expanded means of the Navy's Hydrographic Office. In 1884 California's Mare Island Navy Yard Observatory began to send signals to a time ball in San Francisco, and in 1885 the Hydrographic Office there took over responsibilities for its maintenance and operation.39 Soon other cities with branches of the hydrographic service, including Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Orleans, and Portland, Oregon, had time balls of their own.40 By 1886, authority for Boston's time ball had shifted from the Signal Service to the Hydrographic Office, civic authorities in Akron, Ohio, paid to have a time ball rigged in their city, and under a variety of federal auspices time balls in Savannah (Georgia) and New Orleans joined others in Woods Hole (Massachusetts), Newport (Rhode Island), and Hampton Roads (Virginia).41 A vogue for time balls had taken hold, despite their limited sphere of usefulness.

17 Over the next two decades time balls were erected in a variety of prominent sites. The wife of former United States President Polk opened the 1888 Centennial Exposition of the Ohio Valley and Central States, held in Cincinnati, Ohio, on 4 July when a time signal received from Nashville dropped a time ball and triggered the ringing of gongs. The officer in charge of the time ball at the exhibit tried "to do all the missionary work" he could, for Cincinnati was one of the few places in the nation that vociferously refused standard time.42 A few years later a time ball was placed on the United States Government Building at the Colombian World's Fair, held in Chicago. It was part of the naval observatory's exhibit, which included a master/slave clock exhibit and a display of "chronometers of historical interest and specimens of the best of American manufacture."43 Between 1899 and 1907, just as wireless transmission of time signals was perfected, the Hydrographic Office initiated time ball service in Baltimore, Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Sault Saint Marie (Michigan), Buffalo, Galveston, Duluth, Norfolk (Virginia), Key West, and at Cavite Naval Station in the Philippines.44 In each instance, excluding the last, local commercial organizations materially assisted in the enterprise, mainly by providing permission to use the roof of a prominent building for the apparatus.

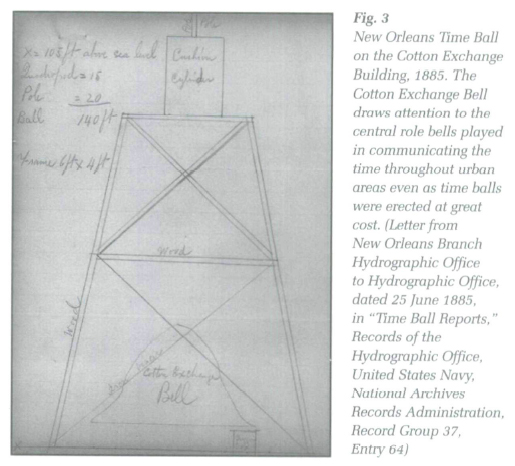

18 A closer look at the history of New Orleans' time ball highlights the monumental nature of the devices. In 1884, the astronomer in charge of Washington University at St Louis's observatory oversaw a time ball exhibit on "the central tower of the Main Building" at the Cotton States Exposition in New Orleans. In addition to releasing the time ball every day at noon, the time signal also regulated "a great many clocks," and was responsible for "a Torpedo exploded in the lake [on exposition grounds]."45 As it neared when the exhibition would be dismantled, several proposals for erecting a permanent time ball appeared in local papers, with justifications focussing on "the advantage of uniform and accurate time... To banks, courts and railroads the value of precisely correct standard time is a matter of practical moment."46 The Hydrographic Office prevailed over the Signal Service, and was placed in charge of the time ball service. In June 1885 a fifteen-foot tower with a twenty-foot pole, placing the ball one-hundred-and-forty feet above sea level, was in working order on the roof of the Cotton Exchange, "the highest building in the city except those having steeples." The ball could "be seen from the balconies, upper windows, or roofs of nearly all houses in the city and from nearly all parts of the river front, either from the decks or riggings of ships..."47 Beneath the ball was the Cotton Exchange's enormous bell, which was struck twelve times each day at noon (Fig. 3).

19 New Orleans' tribute to modern times attracted crowds. Without any notice in papers, "a very large crowd gathered on the streets to witness" the first noon drop of the time ball.48 The next day "an immense crowd on the streets" again waited "to see the Ball drop." But it did not, due to trouble with the telegraphic signal.49 The monthly reports documenting the erratic performance of New Orleans' time ball that span several years throw into doubt the New Orleans Maritime Association's assurances, stated in a letter to the Chief of the Hydrographic Office, that "all the principal jewelers, chronometer makers etc. take advantage of its [the time ball's] indisputable accuracy." Nor is it possible to take as a fact the association's additional endorsement that "many strangers and residents compare their timepieces daily upon the dropping ball."50

20 Until 1909, when "the Time Ball was carried away during the gale of September 20," a hydrographic officer, or someone he dispatched, would hoist the Cotton Exchange's time ball.51 Sometimes it would drop at noon, other times it would not. That anyone set his or her timepiece by it is unlikely; that it imputed to the once thriving port a semblance of efficiency and punctuality is likely, though the descriptions of visitors to the city during this period need be consulted for confirmation. Over the next four years letters were exchanged, meetings held, and surveys commissioned in order to determine where the new time ball should be erected. New tall buildings overshadowed the Cotton Exchange, and the Navy wanted to ensure navigational use of the time ball by moving it to a site visible from all docks, which was almost impossible given the city's location on a crescent-shaped bend in the Mississippi River. But the time ball had never served as a navigational device, and with the introduction of wireless transmission of time signals a few years earlier, the effort to impute navigational value was hopeless. In 1910 the mast and ball on the Cotton Exchange were dismantled; and in 1913 it was clear that the time ball had vanished permanently from the cityscape.52 New Orleans no longer had the political or commercial will to maintain a time ball, in part because a host of monuments enshrining the "Old South" and the "Lost Cause" recast the city as a site of tradition and history rather than of the future, let alone "the now."

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 321 Just as New Orleans' time ball landed on the junk heap, other younger cities replaced theirs with bigger, more elaborate versions, placed atop the tallest of the new skyscrapers that now crowded downtown districts. By the 1910s many ships were outfitted with wireless receivers that picked up time signals sent from several points, including Paris' Eiffel Tower. That urban Americans watched for the drop of the ball is documented, what exactly they were looking for is not. The hydrographic officer in Portland, Oregon, noted in 1909 that he saw many people "standing in the park, on the corners, etc. etc. at noon waiting for the ball to move," which he surmised showed "the close watch people keep on the ball and the value of its existence here."53 The only navigational direction the balls provided was to avid participants in the consumer culture, for they were sited in the most prominent commercial buildings. In 1909 the hydrographic service sponsored the construction of a time ball on the roof of San Francisco's Fairmont Hotel; in 1910 it installed a time ball on the floor of the Philadelphia Bourse; and in 1911 it agreed to fund the erection of a new ball on top of the Maryland Casualty Company Tower, which when completed in 1912 would be Baltimore's tallest building, and one of the taller buildings in the nation.54

22 Around the same time, considerable speculation circulated about where to move New York City's time ball, since the one on the Western Union building was no longer visible. The hydrographic officer stationed in New York City observed that "a visible noon time signal is thought to be desirable solely for the sentimental reason that this great port should not be without one." He explained that "Observatory Time clocks are to be found in nearly every office in this City; that wireless noon signals can be used by almost every steamer; that nautical firms, not only take charge of and rate chronometers, but also when requested send Agents to ships to correct chronometers." He added that "the most conspicuous and best known location in the City," the Metropolitan Life Tower, had a "thoroughly admiral night signal."55 In the end a new ball was erected on the Seaman's Church Institute Building in 1913, and the Western Union Time Ball was discontinued the following year. New York City had enough monuments to modernity; it no longer needed a prominent time ball.

23 During the same period the chambers of commerce, leading businessmen, and city councils of smaller cities seeking distinction petitioned various branches of the navy for time balls. In 1891 the Fall River (Massachusetts) Yacht Club enthused that a time ball would "be a great card for us." Others seeking time balls for advertising purposes between 1905 and 1924 included a large wholesale and retail business in Rochester (New York), the Knoxville Tennessee Bank and Trust, Pensacola Florida's Chamber of Commerce, the Honolulu Photo Supply Service, Jacksonville's (Florida) Board of Trade, a Salt Lake City investment company, Tampa's (Florida) Board of Public Works, a congressman from Alexandria (Virginia), the mayor of San Diego, and a Lynn (Massachusetts) newspaper.56 The Navy did not build time balls for any of these applicants, and the record does not show if private concerns filled the breach. During the First World War the hydrographic office dismantled most of its time balls; by 1922 only a few were in service; and in 1936 the naval observatory's time ball was "decommissioned." Today the few time balls that remain are on display somewhere along San Francisco's and New York City's waterfronts. These outdated, curious monuments continue to serve as registers of a modernity long since past, even if they will never again be dropped daily, except Sundays, at noon.

I wish to acknowledge with gratitude the assistance of Shirley Teresa Wajda, Tom Knock, Malta Braun, the journal's anonymous reader, and Adam Herring. I also wish to thank the National Endowment for the Humanities and Southern Methodist University's Research Council who each provided research funding during the 1999-2000 academic year.