Course Reviews / Comptes rendus de cours

Winterthur Museum's 1999 Winter Institute:

A Review

1 I was first introduced to the Winterthur Museum while I was working on my Master of Museum Studies at the University of Toronto and enrolled in Dr. Adrienne Hood's "Topics in Material Culture" Seminar in 1996/97. Winterthur's video "Why Things Matter" articles in the Winterthur Portfolio would not prepare me, however, for the sheer volume and staggering importance of the Museum's collection. At the urging of an esteemed colleague at Kings Landing Historical Settlement I applied to attend a course at Winterthur, and in January 1999 I had the great fortune to attend Winterthur's three-week intensive program Perspectives on Early American Decorative Arts, 1640-1860.1

2 Winterthur Museum is located in Wilmington, Delaware, and contains more than 89 000 decorative arts objects that were made or used in America between 1640 and 1860. Winterthur Museum comprises the eight-floor, 175-period room museum that Henry Dupont opened to the public in 1951, as well as three floors of permanent and temporary gallery spaces located in a newer addition. Winterthur is also one of the largest teaching museums in the United States. It sponsors three graduate programs in co-operation with the University of Delaware: Early American Culture, Art Conservation, and History of American Civilization.

3 Each year the Winter Institute accepts - approximately thirty to thirty-five individuals with an extremely broad range of backgrounds and experience, from museum curators, educators, and collections managers to antique appraisers. The application process is clear and expeditious, and notification of acceptance (or rejection) is issued promptly. Winterthur offers tuition scholarships to aid with the hefty US$1400 tuition fee. In addition, the Institute arranges for those participants who so desire to be placed with Winterthur staff for the three weeks at $20 per day.

4 The course began on a Sunday morning and continued for eight hours each day, with the exception of Sundays, for the next three weeks. The inaugural lecture, "Understanding Objects," outlined three methodological frameworks that Winterthur staff have developed and utilized over the years. The instructor, Rosemary Krill, Director of the Winter Institute, provided an overview of the "fourteen points of Connoisseurship"2 Charles Montgomery designed in 1961 to evaluate rare, valuable objects. Krill emphasized how Montgomery shifted the focus from the maker or user to the object. The second framework that she discussed, E. McClung Fleming's 1974 "Artifact Analysis,"3 remains the dominant paradigm for viewing objects as social documents. The final framework outlined was Eversmann, et al., "Visitors Approach to Objects."4 The Education Department of Winterthur developed this framework in 1992 by focussing on how visitors react to objects, including how they associate objects with other objects more familiar to them. Consequently, the Department has incorporated visitor perceptions of objects into its research.

5 After three days of introductions and general tours, the course proper began, with each morning taken up with two lectures on a variety of topics, such as eighteenth-century material culture, the transmission of European culture to America, Queen Anne and Chippendale furniture, upholstery, metal, textiles, and glass. These topics only scratch the surface, as the course presented a full history of the decorative arts between 1640 and 1860. Some of the speakers included noted Winterthur staff such as senior curator Donald Fennimore; Brock Jobe, Deputy Director for Collections and Interpretation; John Krill, Senior Paper Conservator; Dwight Lammon, outgoing Director and CEO; and Michael Podmaniczky, furniture conservator and leader of the Windsor Chair Workshop. The roster of guest speakers also impressed: Richard Bushman, Professor of History at Columbia University; James Henretta, Professor, University of Maryland; Charles Hummel, Curator Emeritus at Winterthur; Peter Kenny, Associate Curator of Decorative Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Robert St George, University of Pennsylvania, and many others.

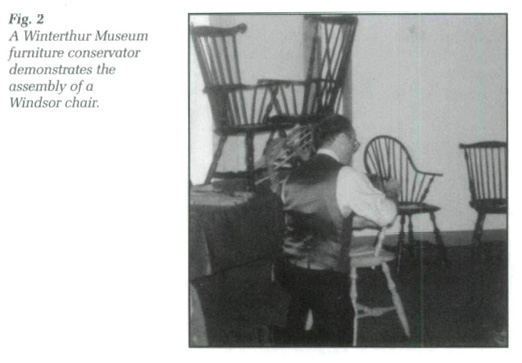

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 26 The program's lectures can be divided into two categories; those providing historical information and those providing information on specific areas of study such as Queen Anne Furniture or English Ceramics. In his lecture on "Seventeenth Century Decorative Arts," Robert St George discussed spatial practices in seventeenth-century homes, such as room placement and usage and furnishings. Kevin Sweeney, Associate Professor of History and American Society at Amherst College, lectured specifically on seventeenth-century and William and Mary Furniture, describing its character, transmission to America, usage and the transition to Queen Anne furniture. James Henretta's lecture is another example of contextual information that was essential to participants' full understanding of the material under study. His discussion of "English Culture in America, 1600-1760," focussed particularly on the transmission of European culture to British North America and the resulting regional variation in material culture that developed from differing settlement patterns.

7 After the first week of the program and a variety of lectures on historical background, the program shifted focus toward specific furniture styles and specific classes of objects, such as glass, textiles, silver and prints. John Krill's "Handmade Paper for the Arts" for example, demonstrates the transition in the program's focus. Krill's session included the identification of paper available before the nineteenth century. He discussed types of paper, uses, and quality. Participants became more comfortable with the various aspects and types of paper production.

8 The morning lectures provided the background for the afternoon activities. Each afternoon began with in-depth period room study that corresponded thematically with the morning lectures. Following the room studies, which Winterthur's highly trained teaching guides conducted, one of the morning lecturers conducted workshops. These workshops provided participants with the opportunity to view the collections more closely and were of tremendous value. The fundamentals of cabinet making and Windsor chair workshops, for example, highlighted the technical side of furniture construction, as the furniture conservator discussed joinery, woodworking tools, varieties of Windsor chairs and assembled a Windsor chair. At the Metal Workshop participants learned the different uses of base metals, their various alloys and how particular pieces, such as kettles, were constructed.

9 There were several reasons for Winterthur's conducive learning environment. The daily activities served to reinforce the morning lectures, and allowed participants to view the artifact collection in a smaller group setting, which facilitated discussion and allowed the instructor to answer more questions. The morning lectures also allowed participants to hear top rate scholars from Winterthur staff and guest lecturers from other museums and universities discuss current scholarship and their areas of expertise. Most speakers provided copies of their papers, bibliographies and other useful handouts. The afternoon sessions, while providing an opportunity to stretch one's legs, more importantly allowed participants to experience lengthy room visits, furniture discussions and closer examination of selected pieces in study rooms. One drawback, however, was that even with cotton gloves, artifact handling was rarely permitted. Many participants agreed that, after so much study and discussion, it would have been useful to get the "feel" of an object. The development of a hands-on study collection of a few pieces would enhance the Winterthur experience.

10 Any free time outside of the lectures and workshops could be spent in the three floors of displays that were open to the public without a guide. The displays explored material culture methodology, and fakes and forgeries. One floor consisted of an in-depth furniture study using Charles Montgomery's fourteen points of connoisseurship. A temporary in-house exhibit entitled "Deceit, Deception and Discovery" focussed on two varieties of artifacts, those that unintentionally deceived individuals and forgeries that were meant to fool. The "Discovery" element highlighted the processes that were used to discover such deceit and deception. It was particularly enjoyable to see Winterthur not shying away from this area and displaying many objects that had duped its curators.

11 Winterthur's teaching guides deserve commendation. Many of these guides have been at Winterthur for years and have developed their own specialties within the collection. Teaching guides led the room studies each afternoon and special study tours on the weekends. Participants ended up spending a great deal of time with the teaching guides who were welcoming, professional and highly knowledgeable. Weekend "Special Study Tours" were optional, but who could refuse a further opportunity to visit the period rooms, which, it should be stressed, were not open to participants without a guide. These tours focussed on areas such as Chinese export porcelain, rugs, clocks, needlework and metals.

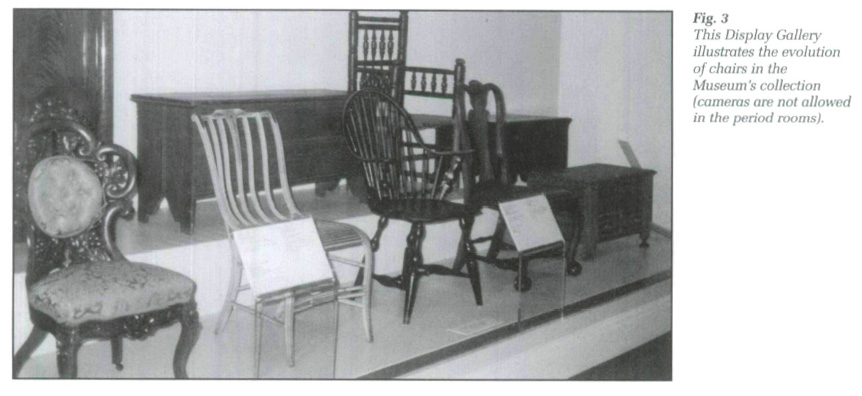

Display large image of Figure 3

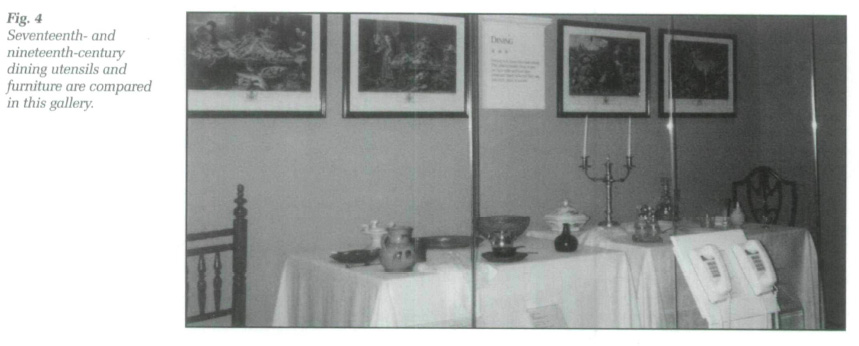

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 412 There were also many opportunities to visit "behind the scenes" at Winterthur. Participants were able to visit Winterthur's collection storage and visit the closed-for-the-season hands-on children's "Touch-It Room." Participants were able to visit the museum's state-of-the-art conservation laboratories and its three libraries, and speak at length with staff in these areas. The library hours were extended for Winterthur participants to conduct research (if time could be found for this exercise). Although the program was full, a number of participants conducted research during the evenings and appreciated the opportunity to do so as the library has an outstanding collection of resources.

13 The Institute also arranged for a number of day trips. One such trip consisted of a visit to three other historic house museums under the aegis of Winterthur, the historic houses of Odessa. Another trip included a visit to Baltimore, Maryland, to visit the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Homewood House Museum on the John Hopkins University Campus. There were also organized visits to museums and galleries in the evening for those participants who had the stamina to attend. Overall, Winterthur provided numerous opportunities for participants not only to acquire a great deal of knowledge about the decorative arts but to apply and foster this knowledge with in-depth workshops and museum visits.

14 Another enjoyable and educational aspect of the program was the interaction and networking with museum professionals from across the United States. Spending three weeks with this group of professionals was indeed valuable in providing a range of contacts, as well as invigorating discussions with thirty other individuals fascinated with the decorative arts.

15 The Institute advertised the program as one designed for an intermediate level. Judging from the other participants, many of whom were at very different stages in their careers and at all levels of museum work, the instructors pitched the course at an appropriate level. Winterthur's ability to integrate material culture scholarship into a decorative arts institute enabled participants to acquire a solid foundation of the decorative arts and material culture. Indeed, after three weeks, participants were able to pinpoint different styles and regional differences in the decorative arts and understand the broader historical context out of which these objects arose.