Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

With Love from the Trenches:

Embroidered Silk Postcards of the First World War

1 On 2 August 1914, the German army penetrated into French territory. Two days later Great Britain, Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, and South Africa became involved. For these Allies the war would last four years.1

2 The separation of women from their husbands and sweethearts caused by the First World War gave a rise in popularity to a particularly individual type of postcard: the embroidered silk. Most commonly made in France, these richly coloured designs were sent home by the soldiers stationed there.

3 One such collection, owned by the author, contains 168 cards sent to members of a close-knit Winnipeg family.2 The largest number of cards in the collection was received by the author's great-aunt, Alexandra, or "Ex" as she was called, from her Irish-born husband Samuel James Patterson. Sam joined the 27th City of Winnipeg Battalion, 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division Royal Expeditionary Forces on 8 December 1914.3

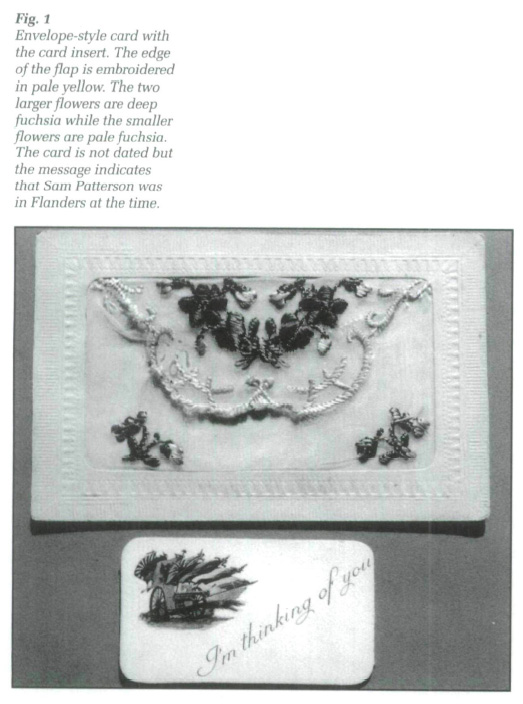

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 Alexandra's sister Ernestine also received cards from Sam as well as from her American-born husband Frederick McClelland. Fred was formerly with the U.S. Army Corps and joined the 78th Canadian Infantry Battalion, 100th Regiment Winnipeg Grenadiers. 12th Canadian Infantry Brigade on 17 February 1916.4 On 13 January 1917, at the age of 27, Fred was killed in action and is buried at Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery, Souchez, France.5 McClelland left behind his wife Ernestine and namesake Frederick, a child born while he fought in France.

5 Isabelle Simpson , aunt of the author, received cards from family and friends alike. Particularly touching are those from Ernest Samuel Walker who joined the forces on 4 July 1915 as a private in No. 5 platoon, B Company, 78th Overseas Battalion, 100th Regiment Winnipeg Grenadiers.6 English-born Ernie has been described as "an old flame" of Isabelle.7 Born in 1900, Bella was fourteen to eighteen years old during the First World War, probably too young for a serious romance. Nevertheless, the cards bear witness to her charm for Ernie has written "To Bella with best love from yours always," "Here's to your health sweet girl," and the long, but touching note that reads:

6 Ernie must have been a close family friend as at least three other cards were sent by him to Alexandra Patterson. Bella also received at least one card from Fred McClelland. Not dated, it wishes her a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. Since he died in February 1917, it may be assumed that he is referring to Christmas, 1916. Regrettably, there are no longer any surviving family members to provide additional information on these men, nor on the women left behind.

7 This collection of silk postcards is valuable, not only for the tangled story they tell of strength, love, patriotism and patience but for a view of the First World War that brings that reality to life. Some messages written in haste are testimony to the trials of the time: war diaries, records, and historical summaries indicate that all too often, particularly grim battles can be linked to postcards with the briefest of messages. For instance, Sam Patterson writes his wife on 16 April 1916: "Belgium. Dear Ex, I hoping [sic] you are quite well and everyone happy under the trial circumstances." In the twelve previous days, the area between St Eloi and the Ypres-Menin road was the scene of activity when "the 2nd Canadian Division lost 1,292 men, battling in the mire for the craters of mines... "8 On June 11 he writes briefly: "To my dear Ex, from Sam." June brought "the pressing Germans...preceded by the heaviest artillery preparation hitherto experienced."9 In November "Canada paid a heavy price for Regina Trench. For weeks the close battle swung backwards and forwards across the battered quarter-mile of trenches...Desire Trench was carried on the 18th...The corps lost 22,000 men on the Somme..."10 Ernie Walker writes Bella on 12 November 1916: "Somewhere in F. Keep your heart up — alls well."

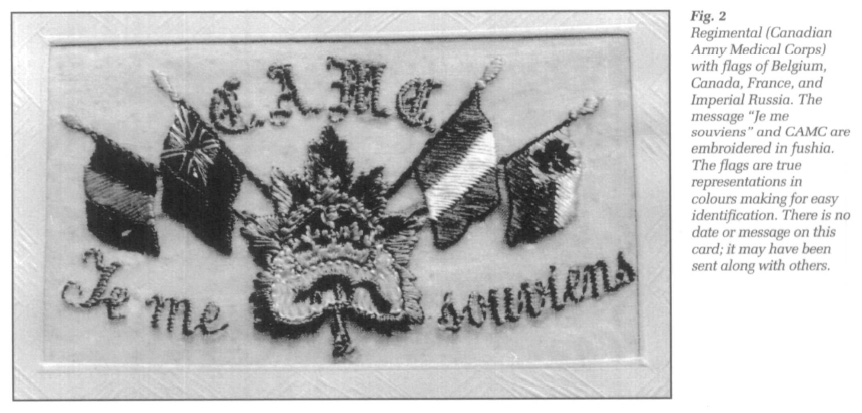

But these embroidered postcards had their origins much earlier than the Great War. The first French cards of this type dates back to 1907. They were known in Austria in 1903 and by 1910 had gained considerable popularity.11 Until the outbreak of the war most designs featured flowers as their main theme. The pansy is the most popular flower shown on the cards in the author's collection but daisies, poppies, lilies-of-the-valley, carnations, and roses can also be identified. Once war enveloped Europe, the major themes soon changed to flags and regimental designs.12 Among the regiments in this collection are Royal Army Medical Corps, embroidered R.A.M.C; Canadian Army Medical Corps, embroidered C.A.M.C; Royal Flying Corps, embroidered R.F.C.; Royal Field Artillery, embroidered R.F.A.; Royal Engineers, embroidered in full; and Canadian E.F. in France ("E.F." stood for Expeditionary Force). One card that is likely an embroidery error is for the British Red Cross Society which is embroidered B.R.S.C.13

8 While France did not invent the embroidered card, she was certainly one of the largest producers. The cards flourished during the war, enjoying particular success with the military. Ports like Calais, Boulogne, Dieppe, Rouen and Le Havre were especially rich in these silks and nearly every shop, large or small, had them for sale. Cards conveying affectionate tidings were by far the most favoured, followed by patriotic sentiments, then regimental badges. As a result, cards in the first category are more plentiful.14 Long after the Great War had concluded, manufacturers continued to make them, supplying troops stationed at Gibralter with the silks until 1926.15

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

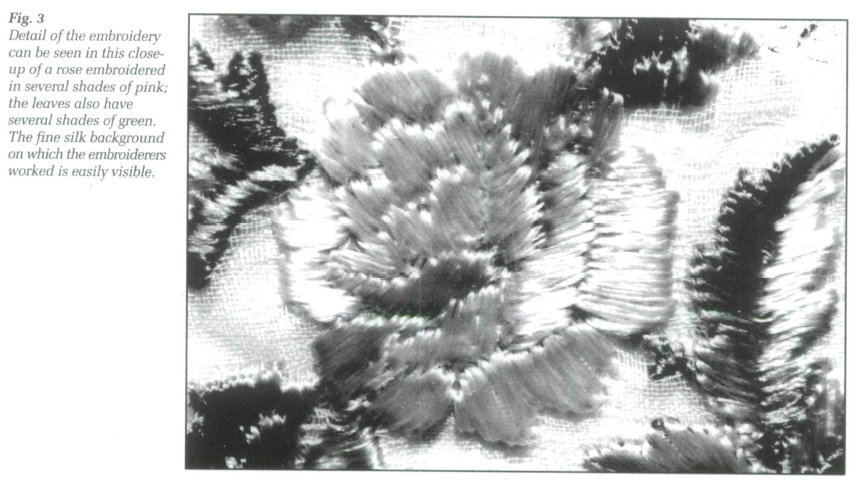

Display large image of Figure 39 All the cards in the collection have been protected against light, and consequently against fading. As a result, the silk postcards in this collection are as dazzling today as they must have been more than eighty years ago when they were made by rural artisans.16 A small quantity of cards worked in England was turned out by refugees from France.17

10 All the cards have similar construction: a white silk rectangle on which the message and design were embroidered. The embroiderers began with long strips of silk about 190 centimetres by 11 centimetres, long enough to accommodate up to twenty-five designs. The strips were starched before embroidery began.18 Generally the silk portion of the card measures approximately 6 centimetres to 1.6 centimetres in width. When completed they were sent to factories for finishing. Here they were attached to a card that framed the embroidery on one side with borders embossed to simulate lace, geometrical, or blossom and foliage designs. The alternate side was a regular postcard back.19

11 There is scant information on the manufacture of the cardboard portion: none of the consulted sources provided this information. However, examination of the cards in this collection reveals that a number of manufacturers appear to have been involved in France, England, and Switzerland. The most frequently seen printers' marks are those of CM, J.J. Saint-Omer-Paris, and H.S. The latter had his border patterns registered as the term "Modèle déposé" appears on those of his manufacture. One card indicates that it was made in France but carries a London address: "Inter-Art Co., Red Lion Square, London, W.C." While most of me cards are printed in French or French plus English, one card that originated in Paris bears five languages: "Carte Postale, Post Card, Cartolina Postale, Parjeta Postal, Bilhete Postal."

12 The back of the card, like a typical postcard, has space for a message and address. One collection card is printed: "Tous les pays étrangers n'acceptant pas la correspondance au recto, se renseigner à la Poste" leaving the reader to wonder how the Canadian and British forces were to comprehend the message.

13 Some of the cards are known to have borne postage stamps and were mailed just as they were. Generally though, the men in the trenches preferred to guard their souvenir silks against damage and enclosed them in the lightweight semi-transparent envelopes sold with the cards.20 Since one message in this collection refers to a "letter under separate cover" this may have been the way that particular card was mailed although no envelopes exist in the collection.

14 More elaborate examples had embroidered flaps covering a small pocket in which a decorative message card could be found; some even had silk handkerchiefs tucked into them.21 Images on the smaller cards represent landscapes, or a couple, and are sometimes the work of well-known illustrators like Xavier Sager.22 Sager drew many of the designs used for these small insert cards that bear mostly patriotic messages. All his cards are signed. G. Meihler designed sepia-coloured landscape war scenes, sometimes showing a soldier with his country's flags.23

15 The subject of the cards is evidently a response to the demand of the principal clientele: the military engaged in the Great War who wanted to give news of life at the front, to send messages of affection to those from whom they were separated. In an analysis of the cards, two principal themes dominate: patriotism and military life on one hand and anniversaries and sentiments on the other hand.

16 Patriotic cards, often showing the flags of various countries, celebrate the participation of the Allies in the war. Certain figures are shown side by side to symbolize the patriotism. of the fraternization of the alliances. The accompanying text is usually of a patriotic nature: "All united," "For right and liberty," "The maple leaf forever," and "Send him victorious."

17 But the sentimental theme dominates with simple messages conveying the thoughts of those in the trenches: "I long to see you," "My thoughts are at home," and "You are ever in my dreams." As well, special occasion cards for Christmas, New Year's and Easter were common and bore more traditional messages of "A Happy New Year" and "Christmas Greetings." More often the messages were personal and dedicated to a loved one: "With love to my dear wife" and "To my dear sweetheart."

18 Occasionally, the written message was a direct response to the embroidered message. One card embroidered "A Kiss From the Trenches" has a written message that reads "Just a Kiss from the Trenches. I wish it was natural then I know I would be home." Another reads "In case you become doubtful P.TO." where the embroidered front declaration is "Ever True." An undated card with the embroidered message "Will soon be home" has Sam Patterson clinging to that thought when he writes:

While undated, the comment of "nine months in these trenches" implies that it was sent fairly early in his tour of duty since the 27th Regiment saw action that began in February 1915.24 Sam had joined the regiment 8 December 1914. Postcards indicate that he saw action for two more years. One of the last postcards Sam sent from France is dated January 1917; the following month he wrote the first of several from Lady Warner's Red Cross Hospital in Ipswich.

19 Although the number of symbolized elements is limited, the variety of their combination and the richness of the colours add a great deal of charm, and give proof of the inventiveness of their creators. In effect, the embroiderers who worked from a series of designs and motifs had a certain margin of artistic licence and placed their own personal marks on the cards through a combination of elements and colours.25 Occasionally the first line of a song, or a well-known line within a song, hymn or anthem has been embroidered on the card: "It's a long long way to Tipperary" and "Send him victorious."

20 The possible list of countries whose flags might appear on embroidered postcards numbered nineteen.26 But for some countries, more than one flag may be represented. For example, there are the three ensigns of Great Britain: the white ensign of the Royal Navy, the blue ensign of the Royal Naval Reserve and the red ensign of the Merchant Navy. A second example applies to Russian flags, one being that of Imperial Russia, a double-headed eagle on a yellow background, the other the Russian civil flag of 1914-17, a tricolour with equal horizontal stripes white over blue over red.27

21 This collection has a number of flags that can be identified: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Great Britain, Italy, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Russia, Serbia, and the United States. As well the International Red Cross flag can be seen. The appearance of the familiar stars and stripes of the U.S. flag also provides a means for dating. Such cards must have appeared after the United States entered the war on 5 April 1917. Frequently, a number of flags were used to create butterflies, the R.A.M.C. insignia, horseshoes, and crosses. One uses four flags to create yet another flag.

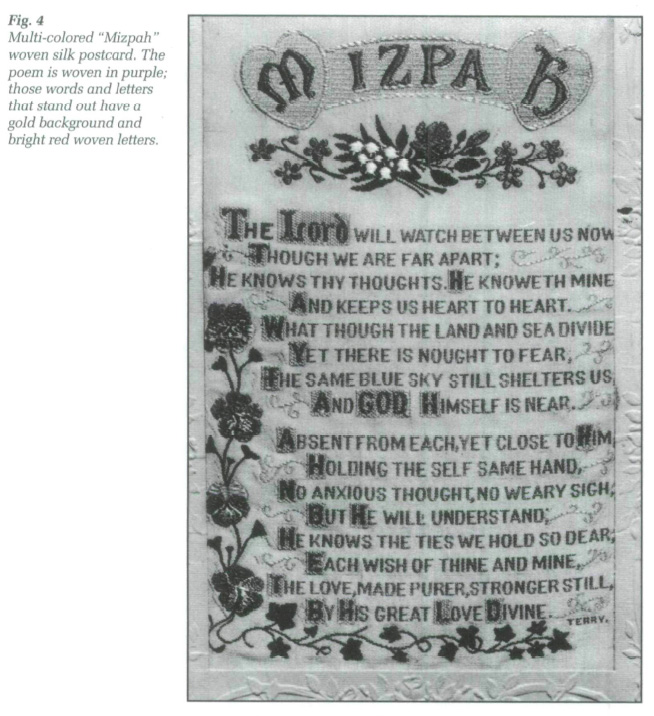

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 422 Early in the twentieth century, Thomas Stevens, who had been producing woven Stevenographs for a number of years, though not as postcards, commercialized woven silk picture postcards.28 Usually the cards show the name of the manufacturer but where they do not there are differences in the border around the picture which normally identifies them. Some were woven in a single colour while others were created using many colours.29 Stevens is known to have produced bookmarks woven with the word, or verse "Mizpah."30 One postcard in this collection has the "Mizpah" poem woven for the front but there are no marks of identification.

23 The Coventry firm of W. H. Grant followed Thomas Stevens in producing woven silk picture postcards. Grant postcards were woven and mounted at his factory until 1941 when it was destroyed during the blitz.31 One of his workers, Beatrice Heath, who began work there in 1910, recalled some of the silk postcard titles, among them "Lead Kindly Light," complete with words and a musical score.32 Grant is known to have produced similar cards with words and music to "Auld Lang Syne" and "Killarney."33

24 Another woven silk in the collection is definitely of French creation. The back of the card shows that the silk was woven by E. Deffrène, rue Montmartre, Paris.34 This silk-woven card titled "Martyr Ypres" is similar to the scenery weavings of Stevens and Grant.

25 The price of silk cards, from one to three francs, was relatively high for a French soldier who could only afford to make the purchase for a special family occasion or to serve as a souvenir. This explains why so many cards of French manufacture bear a text in English — for the British Army and British Empire forces, a favourable currency rate made the cards affordable. The French were also known to have sold the cards to British and Imperial Forces for half a franc or one franc each.35

26 There are also cards that were impregnated with a perfume fragrance.36 However, after more than eighty years the fragrance would have long disappeared and it is impossible to know today whether any of the cards in this collection were at one time scented.

27 The scent of those postcards as well as the beauty of the embroidery must have made the servicemen feel closer to home. One card from Sam Patterson remarked that the front of the card "reminds me of your fancy work." The messages hid from home the filth of the mud trenches and the stench of death that surrounded the men on a daily basis. Soldiers were able to hold the cards and finger the silk, be reminded of the warmth of a smile, recall the gentleness of a touch, and reflect on the reasons for suffering through homesickness and horror. Thus, the beauty of the cards served as a material link for bringing family and friends closer to the hearts of those in the trenches.

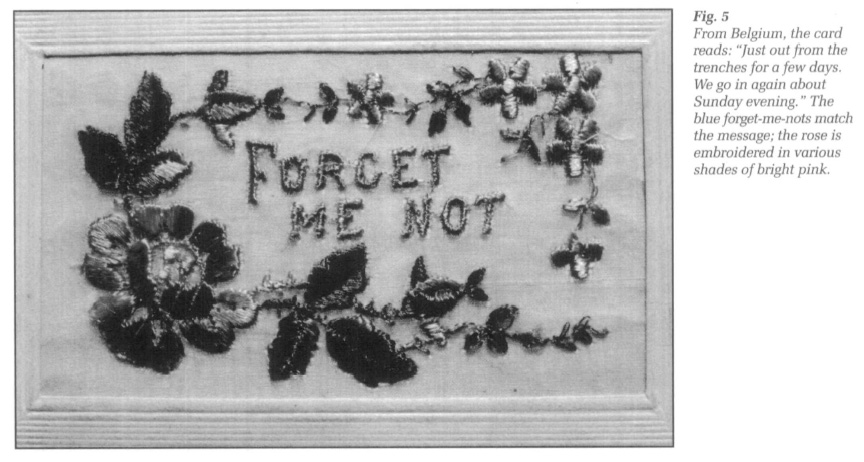

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5