Articles

Wearing Two Hats:

An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Millinery Trade in Ontario, 1850-1930

Abstract

This paper combines the methodologies of historical research and material culture analysis to explore the history of the millinery trade in Ontario. The material studied is a collection of five-hundred hats, from the 1920s to 1930s, old stock from one Sarnia millinery shop. Documentary research in archives and libraries, tracing the rise and fall of the millinery trade from 1850 to 1930, provided a context for the collection. The collections research confirmed the documentary story, but also provided insights into the millinery trade not available from the written record.

Résumé

L'auteure aborde l'histoire du commerce des chapeaux féminins en Ontario en combinant les méthodologies de la recherche historique et de l'analyse de la culture matérielle. Son étude porte sur une collection de cinq cents chapeaux des années 1920 et 1930 qui formait l'inventaire d'une modiste de Sarnia. La recherche documentaire, effectuée dans des archives et bibliothèques, a permis de suivre l'essor et le déclin de la chapellerie féminine de 1850 à 1930 et de situer la collection dans un contexte. La recherche fondée sur la collection a confirmé le récit documentaire mais aussi éclairé des aspects de la chapellerie que les écrits ne pouvaient révéler.

1 This paper is a dialogue between written evidence and material evidence of the millinery trade in Ontario, from 1850 to 1930.1 To explore this topic, I found it advantageous to wear two hats, as a historian and curator, combining the methodology of gender and economics history with that of material history and collections research to help identify and develop a new topic in the history of working women.

2 The impetus for this project came from a collection of five-hundred hats, old stock from Miss Newton's millinery shop in Sarnia, Ontario. Most of the hats date from the 1920s, with about twenty percent from the 1930s and 1940s. When Miss Newton died in 1968, this cache was discovered in the attic of her store, and eventually made its way to the National Museum of Man, now the Canadian Museum of Civilization. This comprehensive group of objects, covering three decades, and all from one documented source, provided a rare opportunity for study. Like many museum collections, this large accession came with only the barest of contextual information. One research goal was to discover more about Miss Newton, her business and her hats, so as to strengthen the documentation of the collection. But the main goal was to discover whether the collection could contribute to an understanding of the past, and in particular, shed light on a uniquely female labour.

3 My methodology was to balance documentary research on the millinery trade with analysis of the collection, both to test the written record, and to extract new information. This paper will present the results of research into the written record and into the material record consecutively, but the actual strategy was to shift back and forth between words and objects, from archives to collections storage.

4 Donning my historian's hat, I began traditional research in archives and libraries. I relied almost exclusively on primary sources. The historiography of women's work in Canada is well represented for nursing, teaching, agriculture, social and domestic work, and factory garment manufacturing, but only a few sources touch on the millinery trade.2 My work was greatly informed, however, by comparison with the American experience in Wendy Gamber's research on the millinery and dressmaking trades in the northeast from 1860 to 1930.3

5 Fundamental statistical information about the trade in Ontario was garnered from census reports and city directories. More detailed information and attitudes toward the millinery business was found in trade magazines, government documents, city histories, occupational guides, biographies and millinery instruction manuals. Each source was evaluated for accuracy and bias. Like many female trades and activities, the millinery business has left behind few written records, and what does exist is incomplete. No doubt there were more milliners than were recorded in the federal census returns or in the trade and commercial sections of city directories. Many milliners carried on small businesses out of their homes, and their work went unrecorded. Nevertheless, the numbers of milliners reported in the census and directories provide at least a sense of the breadth of the trade.

6 Observations about the millinery business in two extant trade journals were both insightful and problematic. The Canadian Milliner, published in Toronto (only 1929 extant), and the Dry Goods Review, also published in Toronto with offices in Montreal, Winnipeg and Vancouver (surveyed from 1891 to 1937) were not written for women who made hats. Aside from a few articles submitted by actual female milliners, these journals were dominated by male contributors who participated in the millinery trade "fraternity," as they called it, as manufacturers, wholesalers and large retailers. Despite this bias, the journals were very useful for charting the involvement of men in the millinery industry, changing it from small, female enterprises to large-scale factories.

7 An essential source was the the millinery trade manual, which proliferated in Britain and North America from the late-nineteenth to the early-twentieth century.4 Most of the instruction guides I found were published in the United States or England. A number of those consulted, however, had a clear connection with Canada, as they were found languishing on the shelves of libraries in Canadian women's colleges and universities. An important source for my study was the 1913 manual, Scientific Dressmaking and Millinery, by Isabella Innes, principal of the Costumer's Art School, established in Toronto in 1890. Scientific Dressmaking and Millinery was written "for the young lady or widow who finds she has to make her own way in the world." Miss Innes, who had many years of experience working for a merchant tailor, revealed to her female students the "scientific" secrets of pattern drafting systems for garments and hats, borrowed from men's tailoring. She claims to have set down in writing all the "secrets of the business [which] had to be learned or rather found out by experience."5 Instructional guides like Scientific Dressmaking and Millinery attempted to formalize a system of learning traditionally built on apprenticeship.

8 A story emerged from the statistics and the discourse, familiar to the economic history of the past century, about the demise of the hand-craft for the assembly line, the sacrifice of small retail stores to the giant department stores, and the usurping of a traditionally female trade by male owners and workers. This trend was already in place by the late nineteenth century, but was not keenly felt until the 1920s. At the same time, a more uplifting story can be told, of the heyday of the handmade hat from 1890 to 1920, and about the highly skilled milliner and the role she played in virtually every town and community in Ontario. The following is a synopsis of the findings.

9 Prior to the 1870s, millinery was allied with dressmaking, and the making of hats, bonnets and dresses was often done by the same tradeswoman, who also sold dressmaking supplies, clothing accessories such as gloves and fans, and garment trimmings. Dressmaking and millinery was one of the few skilled occupations available to women in the nineteenth century. Women who had learned basic accomplishments in needlework at home or at school were able to put their training toward earning an income. Most took on the occasional commission to augment family income, but the more ambitious, or those working out of necessity, carried on full-scale dressmaking and millinery businesses.6

10 The 1851 and 1861 census returns do not differentiate between dressmakers and milliners, but it is clear from the Toronto city directories that some dressmakers concentrated on making hats and bonnets. Of the fifty-two dressmakers in the Toronto City Directory for 1856, nine were also listed as milliners. By 1861/62, there was a separate listing for milliners. Two of the thirteen milliners listed were also dressmakers, and two were also straw bonnetmakers, a specialized trade, requiring a skilled hand to plait the straw, and sew the plaits together in concentric circles to form a bonnet. A cross reference with street addresses in the directories shows that most of these women were from the lower to middle bourgeois, the wives and daughters of skilled tradesmen such as carpenters, printers or shoemakers.7

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 It is clear from advertisements in the Toronto City Directories that a few milliners, such as Mrs Simpson and Miss M. McDonald, milliners and strawbonnet makers on Yonge Street, occupied storefront premises.8 Some milliners operated large businesses, such as Miss Burnett, who according to a government survey on labour and industry of 1889, employed twenty-five people and made regular buying trips to England. Her apprentices trained for three to four years before becoming skilled milliners, when she rewarded them with forty dollars per month.9

12 But many more milliners conducted their trade in their own homes, receiving women friends and acquaintances in their family parlours. These small, domestic businesses, with no overhead and only a small outlay of stock, allowed women with little or no capital to have some income. Many women also laboured in their homes to provide hats and bonnets for the retail trade. Of the few men listed under millinery during the 1850s to 1870s in the Toronto City Directories, most were dry goods merchants, who carried millinery among other clothing and home furnishings. Milliners supplied these businessmen with bonnets and hats they made at home, but occasionally a trained milliner worked in the shop, as evidenced in advertisements such as "William Polley's Millinery, Mantle and Dry Goods Establishment," which boasted as manager, "an experienced Lady from one of the leading Millinery and Mantle Rooms in New York."10

13 The next phase in the story, from 1890 to 1920, marks the heyday of feminine headwear. The introduction of the huge, free-standing hat at the turn of the century, made from a foundation of intersecting wires, and covered in net, finished with velvet or silk cloth, topped with magnificent feathers, flowers and shirred ornaments, was the apogee of the milliners art. Great skill was involved in the manipulation of wire to create a shape, in the draping and shirring of fabric, and in the artistic application of just the right ornaments. Close-to-the-head hats, such as berets, turbans and toques were made from cutting pieces of net, buckram or other stiff material from a flat pattern, and sewing the pieces together to make a three-dimensional hat, which would then be covered with the desired cloth. Observers at the time commented on the skills required to make these most important elements of the early twentieth-century wardrobe: "...a first-class milliner is really an artist. Her hands must be skilful and quick, her touch light and sure. She must have a sense of colour and form, and originality and creative ability."11

14 The number of milliners listed in the Toronto City Directories grew rapidly in the early part of this century. County directories listed at least one milliner for almost every town, village or municipality in Ontario.12 Compared with the late nineteenth century, a growing number of milliners operated shops, being at the same time craftswomen, saleswomen and business-women. The National Archives of Canada and other collections contain remarkable photographs of early-twentieth century millinery shop interiors in small towns in Ontario. Proud entrepreneurs wanted to record their success through photographs of their elegantly furnished and draped shops, sumptuous retreats for their female customers (Fig. 1).

15 Only a few women trained by apprenticeship in millinery work could hope one day to run their own businesses. Many joined the army of milliners in the large workrooms of department stores in the first decade of the twentieth century. A series of photographs of the millinery workrooms of the T. Eaton Company department store in 1903-04 clearly shows the handcraft nature of the work at this time (Fig. 2). Some workers are manipulating loose coils of wire into hat frames, while others are cutting, sewing and applying finishing materials by hand. The millinery department in the Eaton's store was created in 1878, and by 1900, employed "several hundred young women who are kept busy to supply the enormous demand for Eaton headwear."13

16 Ironically, the highest achievement of millinery artistry and commercial success held the seeds of its own demise. The consumer demand for hats spurred improvements in the manufacture of millinery, changing a trade that was almost entirely manual to machine production. Wholesalers and manufacturers who supplied to the millinery trade were growing rapidly by the turn of the century. In 1909, there were fourteen wholesalers to eighty-eight retailers in the Toronto City Directory, all of them men. Instead of hats being made from scratch in the workrooms of small shops and even in the large department stores, all or parts of the process were now being performed by machine. The foundations of women's hats — the wire and buckram frames — could be bought ready-made, along with actual finished hats. The large department and dry goods stores, which had for some time sold ready-made garments, were the first to add these factory hats to their stock.14

17 A great impetus to the women's hat industry was the vogue for the bell or cloche-shaped hats of the 1920s. Compared with the elaborate hats of the first two decades, the cloche was an understatement, as explained by the fashion editor of the Dry Goods Review, "when skirts are short, nothing is more important than stockings and shoes, and the simple little hats must not detract."15 The cloches were made of cloth and straw, but felt became a common material for the first time in women's headwear. Manufacturers began to realize that straw and felt cloches could be factory-made in great quantity, in the same way as men's hats. The simple shapes and minimal decoration made the cloche ideal for mass production, and hats could be produced and sold for a fraction of the cost of the handmade hats of a decade before.

18 The Dry Goods Review and the Canadian Milliner clearly show the transition from millinery workroom to factory floor. Despite that, contributors in general advocated the ready-made trade, they paid homage to the handmade hat, and bemoaned the demise of the millinery workroom. One writer warned that, "If the public are still able to buy hats from retail millinery stores at $1.49, or so, how can a millinery store even pay its overhead?...As an old millinery man, I would not like to see the end of the many milliners who are striving for a decent living."16

19 But the transition was inevitable, as indicated in statistics from the Censuses of Canada. In 1911, there were 5567 milliners in Ontario. Despite tremendous growth in the provinces's population, the number of milliners had dropped to 1067 by 1931. Similarly, in 1911, Toronto boasted 1215 milliners, which had dropped to 441 in 1921.17 By the 1950s, the once-thriving custom millinery trade had all but been eclipsed.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 220 These general parameters of the rise and fall of the custom millinery trade have been gleaned from both statistics and discourse, but how do they relate to Miss Newton and her hats? How does the experience of one particular milliner correspond to the aggregate? Can the Newton hat collection provide details about the millinery business that is lacking in the written sources?

21 Miss Newton's story has been pieced together from oral history, scanty archival documents and newspapers.18 She entered the millinery trade at the age of thirty-five, perhaps by necessity: she was responsible for the care of her older brother, sister and mother. She opened a shop on the main street in her home town of Petrolia in 1918. Petrolia was a former boom town, based on the discovery of oil, but by 1918, production had waned, and the population had shrunk to about 4000. The next year, she bought out the "Elite Millinery" business on a prosperous commercial street in the larger nearby town of Sarnia. Sarnia was a prosperous manufacturing town of 9000, on a major waterway and the terminal point of the Grand Trunk and Erie and Huron Railways. Miss Newton's hat shop, along with one other lady milliner and several dry goods stores selling millinery, supplied the women of Sarnia with hats, whereas in Petrolia, Miss Newton remained the sole millinery supplier. She prospered in the 1910s and early 1920s, with two milliners and one apprentice on her payroll. In 1929, one of her appentices, Jessie M. Todd, became the manager of Miss Newton's Sarnia store, and later Miss Todd opened her own millinery business. By 1930, Miss Newton was "seriously embarrassed financially" and closed down the Petrolia store. It is likely that she overstocked during the previous few years, and could not sell all the hats, which eventually found their way to the museum. No doubt The Great Depression exacerbated her situation, but her business did not improve afterwards. In 1946, she closed down the Sarnia store. She continued to carry on a small business in Petrolia until 1953.

22 Unlike the majority of women who entered the millinery trade between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four, Miss Newton started her career later in life. Perhaps her familial demands required her to take on a paying job. But like the rest of her sister milliners, Miss Newton followed the pattern: she opened shop in the optimistic 1910s, to find herself foundering by the end of the 1920s.

23 I will now put on my curator's hat to report on the Newton hat collection. The collection was studied to test the written record, but also to extract new information not otherwise discernable. The hats were first discovered in 1971 by the late Katherine Brett, then Associate Curator in the department of textiles at the Royal Ontario Museum. When Miss Newton died in 1968 a local historian in Petrolia who had purchased the store and adjoining property, contacted Mrs Brett about the possibility of acquiring the contents of a "filthy old loft." Mrs Brett made a selection of forty-seven hats, and notified the registrar of the National Museum of Man about the rest, almost five-hundred hats. At the time, the History Division was actively developing its collections, and decided to accept the balance of the hats in their entirety.19 Today, such a large collection would no doubt be rejected because of space and fiscal restrictions, and, like Mrs Brett, current curators would likely make a small selection, choosing the finest, or representative examples, and eliminating duplicates. The research potential of such a small collection, however, would be greatly reduced. The larger the collection, the more opportunity there is for comparison and for discerning patterns in technique, materials and production. Duplicates are very important to analysis, because they demonstrate Miss Newton's own method of selection and manufacture. Hats in partial production, or modified, or poorly made, also contribute to the research. Even if the whole collection were documented through photographs, the possibility of close material examination of the actual objects, and the new information from that analysis, would be lost.

24 The large sample proved to be both a blessing and a challenge. Where to start? Luckily, the Canadian Museum of Civilization was in the process of digitizing its collections, and the entire group of hats was photographed and available for viewing on compact disc. The hats themselves were stored in open bins accessible by ladder. I commenced with an open-minded perusal of the collection, both the images and the artifacts. My first impression of the collection was sheer delight in the variety of form, colour and ornament. I also observed the preponderance of cloche-style hats; the materials, such as felt, straw and fabric; some of the consistencies in design; hats in varying stages of completion; completed hats with manufacturers' labels; and the evidence of machine stitching and finishing. After these intial observations, I began to form questions that could help with understanding the collection, as well as the milliner's trade: what range in date do the hats represent? How many are ready-made and how many handmade? Of the ready-made hats, where did they come from? Did Miss Newton make or alter hats? What materials were used? What types and range of designs did Miss Newton favour? What range in price did Miss Newton stock?

25 These questions required a detailed level of analysis for which I lacked technical ability. I was fortunate to obtain the assistance of trained milliners in my research, including retired milliner Mrs Ina Shale,20 who has practiced traditional craft methods in Toronto for fifty years, and Madeleine Cormier, a gifted Ottawa milliner who has more recently entered the field. On an ongoing basis, these milliners helped me to develop a millinery literacy: an understanding of the aesthetics and techniques of the trade, and the various categories of materials and methods of manufacture.

26 A second phase to the collections analysis was a more structured study by Ruth Mills, who has had twenty-three years of experience in researching and fabricating historical reproduction costumes and accessories, especially millinery.21 She examined digitized images of over half the collection, and physically analyzed 128 hats. As a pilot project, the study concentrated on cloche-style hats of the 1920s (dating was largely determined by comparison with the Eaton's catalogue) for comparison purposes. In addition, she chose hats to study that were typical in shape or style; similar except for small details; obviously produced in a factory — either because of the presence of a label, or a factory technique; custom or handmade hats; and hats untrimmed or unfinished. The report also includes detailed cataloguing, analysis of techniques and materials, glossary of millinery terms, bibliography and material samples.

27 The hats were organized by type of construction: fabric or pattern hats made of material that was cut into shape, and which, when assembled, achieved the shape and structure of the hat; foundation or buckram hats, with an understructure of fabric and/or wire; wire hats in which the hat receives its support solely from a network of wires; felt hats made from a hood, or unstructured cone, which was then moulded into a hat shape; woven straw hats, made from a hood or body that is woven in one piece and usually moulded; and plaited or straw braid hats, sewn together in a spiral. Many hats used a combination of these construction techniques.

28 This study established the source of many of the hats. Despite local legend in Miss Newton's home town of Petrolia, which maintains that she made all her own hats, most of the hats were ready-made. Over half the hats have makers' labels and/or handwritten price tags, making it possible to establish their origin and price ranges. Miss Newton ordered from a total of forty establishments, most of which were Toronto firms, but she also ordered from Vancouver, Montreal and New York. Information on these companies was found in the Dry Goods Review and the Canadian Milliner. Most firms manufactured their own hats, but also imported hats from the United States, Great Britain and Europe.

29 Certain characteristics of machine production were identified in the labelled hats, so as to establish the origin of unlabelled hats in the collection. Machine-blocked felt and straw hats were often simple in shape, and displayed a clear crease at the headsize (headband) line, created by the pressing machine, as well as a shiny, sometimes crinkled, finish, from the pressure of the machine. Machine stitching was evident in many hats, especially chain stitching, which was achieved on an industrial chain-stitch machine. Hats with these characteristics could not have been produced in a small millinery shop.

30 The variety of ready-made hats Miss Newton had hoped to sell to the ladies of Sarnia and Petrolia attests to the inroads that the factory hat had made in the millinery business, even outside the larger urban centres. The Newton collection provided me with an idea of the range and scope of Miss Newton's business, which was much wider than I had anticipated. I thought a smaller town milliner would have had a much more circumscribed operation. However, during her perusal of the collection, milliner Mrs Shale pointed out that in her opinion, the styles were fairly conservative, reflecting the needs and desires of a provincial town. Since I have been concentrating on the production and distribution of goods, I have not investigated this observation. A future avenue of study would be to analyze the collection from the point of view of consumption: to explore the relationship between a milliner and her customers; the kinds of choices women made in purchasing such an important a piece of apparel; and the role hats played in personal presentation.

31 The quality of design, materials and workmanship in many of the hats made by wholesale firms and ordered by Miss Newton was immediately obvious to Ruth Mills. Evidence from her study shows that factory production did not necessarily mean lesser quality. Some firms had consistently good design and execution, such as the John D. Ivey Company of Toronto, from which Miss Newton ordered over fifty hats. No doubt shoddy hats were also available and perhaps sold by Miss Newton, but clearly this surviving collection shows that Miss Newton showed judgement and taste in her choice of ready-made millinery.

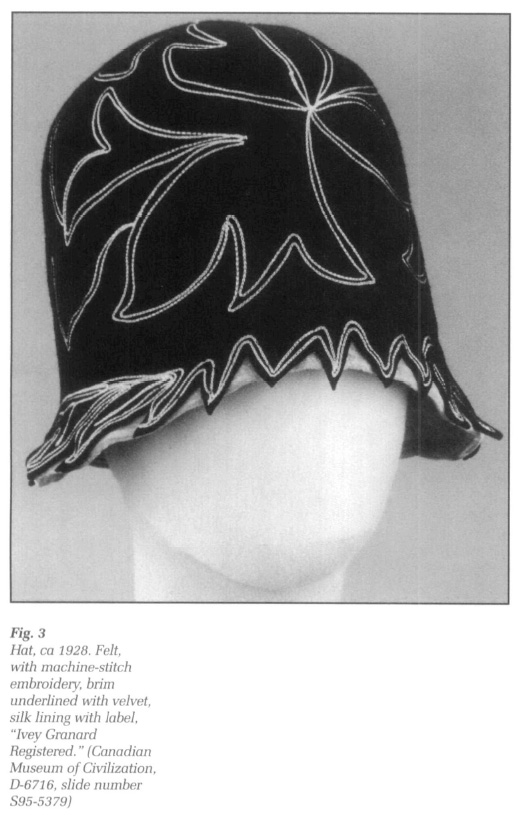

32 An example of an Ivey hat is shown in Figure 3. The basic form is simple to produce by felting, blocking and finishing machines. The design, however, is excellent. Made of light weight felt, the cloche features metallic chain-stitch embroidery in leaf shapes around the crown and dentilled brim edge. It is undertrimmed with tan velvet, machine stiched in several rows one-eighth of an inch apart. The lining is hand-sewn into place, and the label attached with zig-zag stitching. This hat was in the higher price range at $9.75. Cost depended on the quality of the design and materials used. Another phase of the research will be to compare these prices with department store catalogues and advertisements.

33 Miss Newton was, like most millinery retailers, a maker of hats as well as a seller of hats. The paucity of handmade hats in the collection is probably because, being specially made for particular customers, the custom hats left the store upon completion. However, some evidence does exist of the. scope of Miss Newton's millinery craft. First, the collections analysis determined some of the characteristics of the hand-formed hat, including the use of high quality materials such as fur felts; the separate treatment of crown and brim, made apart, and then sewn together; an indentation at the head-size caused by cord tied in place on the hat block; hand manipulation of the brim or crown after basic shaping has occurred; unique, flowing, natural, soft or complicated shaping, or awkward and clearly hand done manipulation; irregularities in the angle of cut edges done by scissors, rather than a cutting machine; and traditional construction techniques, such as wire framing. Only one hat in the collection bears the label, "Miss Newton Hat Shop" (D-6754). This wide-brimmed hat was constructed in the traditional manner of buckram foundation, reinforced with wire, and finished with black velvet cloth. Mrs Shale pointed out several faults in its construction, notably that the draping was amateur, and puckered at the crown. This hat was probably the work of an apprentice, which explains why it did not sell. Although it was difficult to distinguish the shop-made from the factory-made hats, since some of the labelled hats showed signs of handwork, the report identified ten out of the 128 hats examined were completely handworked, and were likely made in Miss Newton's shop.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 334 Some of the most revealing items in the collection are hat forms in various stages of production. An example is a buckram foundation for a beret, ready to be covered with finishing material. It is clearly handmade, probably by Miss Newton. The piecing is very complex and indicates a professional hand. There are several unfinished hat forms, which Miss Newton would have ordered from the factory, to be finished by herself with the addition of brim, ribbon and trim (D-6929). These straw, felt and buckram forms or foundations, pressed into shape by machine, were ordered from wholesalers or manufacturers. They have the original paper lining hand-tacked inside, attached by the wholesaler for shipping purposes. The growth of millinery supply houses was clear in the written record, and these machine-made forms confirm that individual milliners ordered from the wholesalers, as the "custom" part of the milliners' trade in the 1920s often consisted of trimming ready-made forms. Examples of finished hats using these crowns indicate how Miss Newton would have individualized hats based on factory foundations (D-6866).

35 Other evidence from the collection shows that another important part of the custom millinery trade was the renovating or remodelling of old, or even new hats. Some felt and straw hats appear to have been taken apart, cut and restitched, (D-6996), and some have had their trimmings removed, ready for a new treatment (D-6922).

36 In many ways, the collection confirms patterns in the written record. The millinery trade was undergoing a drastic change by the 1920s. The mechanization of women's hat manufacture permeated not just the larger department stores, but the small millinery shops as well. Custom milliners had to change their business tactics, shifting from making all their hats by hand to ordering ready-made hats from the growing numbers of manufacturers and wholesalers. The Newton collection confirms this acceptance of the ready-made hat, and shows the variety and quality of wholesale hats that were available. The collection has also revealed data about the breadth of the milliner's business, absent from the written sources. The stock of even a modest milliner was wide, stretching across Canada, and beyond.

37 The artifact study also indicates the presence of traditional millinery handmade craft, in the few extant handmade hats in the collection. It is clear from hats partially-finished, or in an altered state, that the custom milliner's business relied a great deal on the maintenance and renovation of hats for her loyal customers. Milliners made use of new factory products, but altered them to suit their own, and their customers' needs.

38 The relationship between the written record and the material evidence has been very important to my understanding of the millinery trade. These two sources have informed one another, mutually posing and answering questions. The Newton collection allowed me to verify the documentary story, but also served to fill in some of the blanks left by the textual records. Wearing two hats has given me both an intellectual and tangible appreciation of the milliner's art.

I would like to thank Penny Clelland, Madeleine Cormier, Ken Heaman, Ruth Mills and Mrs Ina Shale for their contributions to this project.