Articles

Material History as Cultural Transition:

A La Ronde, Exmouth, Devon, England

Abstract

The sixteen-sided house of A La Ronde in Exmouth, Devon, England, built around 1795, was owned and furnished by Jane and Mary Parminter, who decorated its interior with extensive designs of shells and other natural gleanings gathered from the beach below. The Parminter lathes had their own money and never married; they specifically left the house to the female line of the family. In 1991 the house was bought by the National Trust and opened to the public. At A La Ronde we see heritage created through the transformation of female private eccentricity to public high status National Trust exhibition. This transformation embraces issues of the female role, domestic artistic creation, and notions of personal integrity. Heritage emerges as the dynamic interplay between history and people through its construction of aesthetic and meaning.

Résumé

La maison à seize côtés de A La Ronde à Exmouth (Devon), en Angleterre, construite vers 1795, a appartenu à Jane et Mary Parminter, qui l'ont meublée et décorée à grand renfort de motifs de coquillages et d'autres éléments naturels glanés sur la plage située en contrebas. Les demoiselles Parminter étaient indépendantes de fortune et ne se sont jamais mariées. Elles ont expressément légué cette maison à la lignée féminine de la famille. En 1991, le National Trust l'a achetée et ouverte au public. Avec A La Ronde, nous voyons un patrimoine créé parla transformation d'excentricités féminines privées en exposition publique de renom gérée par le National Trust. Le rôle de la femme, la création artistique domestique et certaines notions d'intégrité personnelle sont autant de questions qu'englobe cette transformation. Le patrimoine représente l'interaction dynamique entre l'histoire et les gens par sa construction de l'esthétique et du sens.

1 A major issue in material culture studies focuses upon the issue of how "heritage" is achieved, that is, upon how some conjunctions of material evidence acquire the status of political, community and aesthetic value, and some do not. This raises questions about the nature of "fine" and "folk" art (as discussed, for example, at the 1997 Folk Art conference at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax, in 1997, reviewed by Gerald Pocius in 1997),1 about authenticity and value, gender, and the relationship between objects, place, and national agendas.

2 All these issues, together with a significant link between Devon and Canada, are played out in the political history and material culture of the Parminter family and their house A La Ronde, at Exmouth, near Exeter, Devon, England. This paper will concentrate upon the double transition shown first in the creation of the house, which involved the translation of beach gleanings, that is, nature and rubbish, to culture and art; and second, in the transfer of this product from private, home-centred construction to public, prestigious National Trust exhibition.

The Parminter Lathes and A La Ronde

3 In 1784, following the death of her father, John Parminter, Jane Parminter2 embarked on a continental tour accompanied by her invalid sister Elizabeth, her orphaned cousin Mary (see Appendix A), and a London friend, Miss Colville. John Parminter had been a well-off wine merchant and manufacturer of building materials, whose daughters were his only surviving children, and therefore his heirs. At this time, Jane, born in 1750 and so thirty-four, was unmarried (which she was to remain) and wealthy enough to please herself. Jane's Diary provides a detailed account of the party's travels during the summer months of 1784. On June 29 they visited the Prince of Condé's palace at Chantilly and Jane noted "the Cabinet of Curiosities in which are ... spar, coral, amber, crystal, seeds of plants, shells and many other natural curiosities." Jane's Diary ends when the party reached Burgundy, but other material shows that they continued south, visiting Germany and Italy before returning to England in 1795, shortly before Elizabeth's death.3

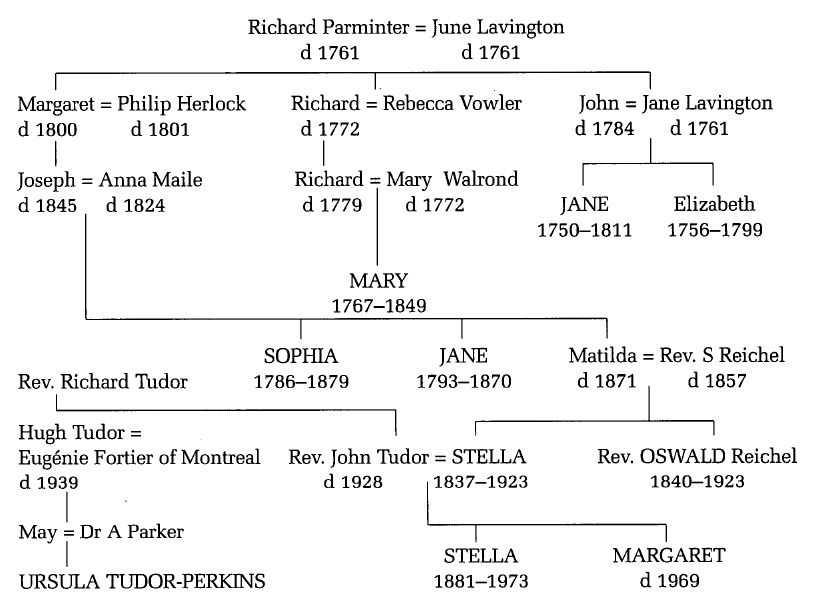

4 Jane and Mary plainly intended to build a new house that could embody their view of the world, and they fixed upon Exmouth, down the River Exe from Exeter, on the south-east Devon coast. By the later eighteenth century Exmouth had developed from a small fishing village to a relatively fashionable sea-bathing watering place, on the strength of its mild climate (for which south Devon is still famous) and its picturesque pastoral surroundings (the Exe Valley still has one of the most famous and appealing fieldscapes in England, with the hills of Dartmoor on the western horizon). By the 1790s the principal landowners, the Rolle family, had built houses to provide for the new visitors and residents, who included the estranged Viscountess Nelson and Lady Byron, Mrs Clarke, the mistress of the Prince Regent's brother, the Duke of York, and the former prime minister, Lord Bute. A certain femininity of society is perceptible; and by the 1820s the town had a theatre, a club and assembly rooms.4

5 Jane purchased land on the hill above Exmouth, between Nutwell Court, home of the Drake family and Bystock, renowned for its octagonal summerhouse paved with 23 000 sheep's hooves, and overlooking the Exe Estuary. The house, A La Ronde, seems to have been designed by Jane in conjunction with connections of the Parminters, John Lowden and his son John, who operated as builders and architects, chiefly in Bath.

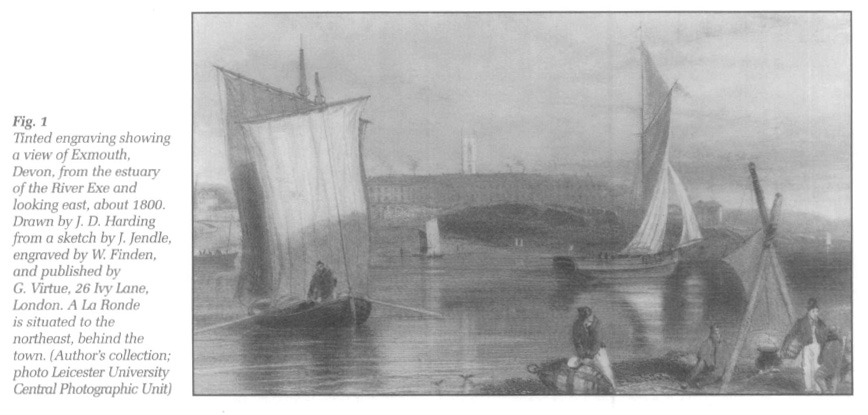

6 A La Ronde was constructed as a sixteen-sided building and eventually it was accompanied on its east by a building complex known as Point in View that included a small chapel, a school, and almshouses.5 The house itself was entered at first floor level, with the Octagon as the focus of the floor, from which radiated the principal living rooms, the Drawing Room, Dining Room, Library, Study and Music Room. The Drawing Room has a remarkable feather frieze and borders, and a chimney board created by the Parminters from a water colour of St Michael's Mount surrounded by shells to form a miniature grotto, and with neo-classical engravings cut out and mounted on cards applied to the overmantel. The second floor contained various bedrooms and boudoirs.

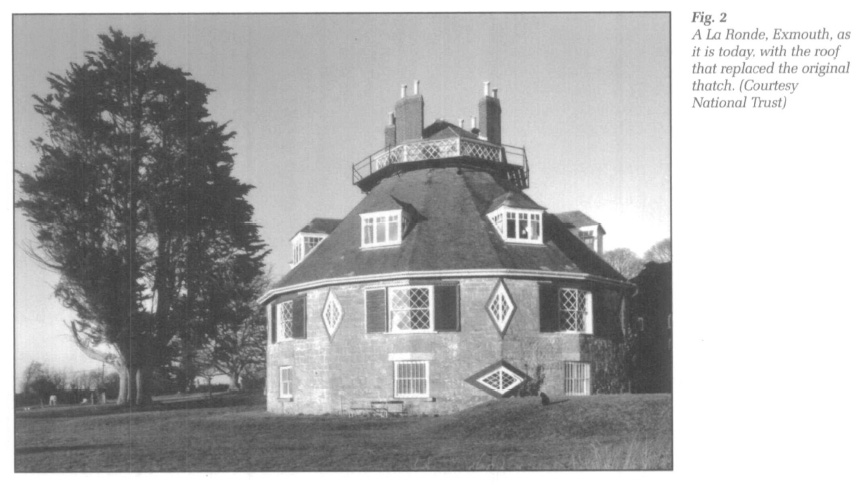

7 From the second floor a narrow staircase leads to the Shell Gallery: these two rooms are the most extraordinary in the house. The two short flights of the very narrow stairway are painted with vaults and pointed arches encrusted with bands of shells fixed directly to the walls. At the first landing a grotto has been contrived around a looking glass above a glazed case filled with shells, mirrors, quartz lumps and quillwork. At the second landing there is a similar glass-and-shell grotto, featuring also a doll's house facade in quillwork. The left turn leads into the Shell Gallery, with above its entrance a crown painted by the Parminters in honour of George III in 1800. The walls of the Shell Gallery were originally completely covered with ornamental shell work. The design embraced a zigzag shell frieze above a clerestorey of eight diamond-paned windows, each within a shell-encrusted recess. Between the windows are pairs of feather work panels showing birds with mosses and twigs. The whole involved many years of devoted labour, using largely material gathered in the neighbouring woods and fields, and on the seashore below.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 Jane died in 1811 and is buried in the chapel at Point in View. In 1849 Mary, too, died and was buried near her cousin. Her will mentions an "obelisk, fountain, shellary, hothouses, greenhouses, sundial, ornamental seats and ornamental gates" in the grounds, so clearly the lathes' ornamental crafts had not been confined to their house. Nothing informative, however, survives of these outdoor efforts.

9 Mary's will also specified that A la Ronde and its contents should be preserved intact, and that only unmarried kinswomen should be eligible to inherit. Accordingly, two unmarried cousins, Jane and Sophia Herlock, inherited, to be followed by their niece Stella Reichel. However, changes in the law allowed Stella to break the trust and transfer the property to her brother, the Rev. Oswald Reichel, the only male owner the house has had. In the interests of "modernisation" he made a number of fundamental changes, in the course of which considerable expanses of the lathes' shell and feather work were destroyed. Reichel lived in the house from 1886 to 1923, following retirement from his post as Vice-Principal of Cuddesdon College, Oxford6 (a theological college, and not one of the colleges of the university).

10 In 1887 Reichel had married Julia Ashenden, but the marriage was childless and so after her husband's death she attempted to sell the property on the open market. By chance a niece, Margaret Tudor, daughter of Stella, saw the advertisement for the property in 1929 and bought it at auction, although she was not herself well-off.7 In 1935 she opened it to the public, and it has remained open ever since. Part of the land attached to the house had to be sold in order to finance the house, and in 1969 Margaret died, to be succeeded by her sister Stella. She lived on in the house until her death in 1976.

11 Ownership of the property devolved upon Ursula Tudor-Perkins, who was descended from the marriage between the first Stella's brother-in-law and Eugénie Fortier of Montreal. Ursula appreciated her inheritance very fully, and by then, the house had begun to attract the attention of the artistic world and articles had appeared in the well known journal Country Life. Ursula negotiated the purchase of the property by the National Trust and in 1991 the transfer of the house, its contents, and the remaining land to the Trust was completed. It remains open to the public, while money is raised to continue the work of restoration.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Key Issues in the Parminter Construction 1795-1811

12 Between 1795, when Jane and Mary returned from the ten-year-long tour of European cultural sites, and 1811, when Jane died, the A La Ronde project was conceived and brought into being, for although Mary seems to have continued to decorate the house alone between 1811 and 1849, and although her will did not come into operation until this date, it seems clear that Jane was the moving spirit and that the intentions expressed both in the house and in the will were primarily hers. Given the significance of this relatively brief period of sixteen years a number of key issues arise, and these revolve around the historical context of the first decade of the nineteenth century, the positioning of the Parminter cousins within it, and the constructions of their individual gaze through transformations of the material world. Within this are questions relating to the perceived appropriate relationship with nature, the bearing on this of gender and celibacy, and the role of the collecting process.

13 By 1800 the English middle class, with its landed tendency and its integral relationship with the trading opportunities offered by eighteenth-century early imperialism and capitalism (to use a useful if rather omnibus term), had emerged as potentially the most powerful social force in the country. This process was assisted, rather than damaged, by the long wars against revolutionary France and Napoleon (1793-1815, with short intermissions) as a result of the manufacturing developments that the wars generated. The Parminter lathes themselves were surrounded by a Jane Austin-like protective walling, in that we could read the narrative of their peaceful, inward-looking lives without realising that a bitter and ideologically powerful European-wide war was being fought during their crucial years at A La Ronde, some of it less than thirty miles away from their seaside home, but the economic and political results of the war and the ultimate British victory affected them as it did the country in general. The effects of bourgeois prosperity and its contemporary links with liberal notions of personal freedom, gender equality, and consumption choice, are clearly marked in the Parminter ménage.

14 The relationships between commercial prosperity and production, and the growth of the romantic imagination and the consumption of goods as spectacle has been traced by Colin Campbell. As the imagination of desire is stimulated by the flow of production, so what we perceive as the marks of the romantic gaze emerge: consumption by "seeing," with the vision directed towards domestic interiors, public exhibitions and eventually shops; the desire for the exotic other in nature and culture; and the willingness to transgress previously forbidden boundaries. With this is connected that strong vein of taste known as the Gothic8 that, in point of history, developed as early as when the first acknowledged Gothic novel, Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), was written and so preceded what is conventionally known as the Romantic period, the first generation of whose authors (Wordsworth and Coleridge) were writing in the 1790s. There is a sense in which the Gothic was a reaction against the sweet reason and hopes of universal enlightenment posed by the high modernism of the earlier eighteenth century. "Gothic" restated the dark underbelly of unreasonable human nature, and in stressing the fragmented, unconnected, carnivalesque character of life and spectacle undermined the notion of the essential self occupying a unique biography comprising an integrated sequence of intelligible interconnected and consciously self-directed events.

15 These streams of thought and feeling united in a powerful moment during the later years of the Napoleonic Wars, from the point in 1809 when the British Army in the Spanish Peninsula under Wellington first began to deliver a significant series of victories up to the climacteric of Waterloo (June 1815). For the present purpose, one important element here is the changing view of material and its relation to the exotic other, whether of the world outside Britain, of nature, or of the past. As, for example, the collecting activities of Charles Tatham in Italy in the 1790s show,9 later eighteenth century taste did not recognise the quality of authenticity as intellectually or aesthetically significant: objects were equally valuable whether they were ancient pieces, Roman copies of ancient pieces, contemporary productions in antique styles, or any combination of these. The criteria was not a perceived integral or metonymic relationship to recognized historical or external sequences, but rather the perceived aesthetic correspondence between the superficial appearance of the piece and the imposed scheme of which it was to be a part: sculpture was assessed against its capacity to grace a predetermined landscaping scheme or candelabra in the Egyptian style against their ability to enhance a room design.

16 Around 1800-1825 this sentiment changed to one in which material took on an essential character in which it was perceived to possess an essential and indissoluble integrity with the distant time or place from which it had come. The extensive mythology that became attached to material from the battlefield of Waterloo is a part of this; so is the display of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum (1817) or the exhibition produced by Belzoni in London in 1821 of a replica of the newly-discovered painted tomb of Pharaoh Seti I, among many other events. As confidence in the essential nature of the individual dwindled, and as the superabundance of successful production, with its imperial consequences, transmuted to the consumption of material through owning and seeing, so inevitably material objects took on the essential qualities that people no longer felt able to claim, and the scene was set for the ensuing developments in our century of identity through material.

17 The positioning of the Parminter lathes within this nexus is clear. They had inherited a comfortable competence in a generation in which they were able, as women, to choose where and how they would live, and to evade successfully any pressure that might be put upon them to marry. Their money had come from the wine trade — traditionally a gentleman's business — and from links that their father had had with Lisbon and the Portuguese establishment, both fundamental building blocks in Wellington's military success. They had been able to travel extensively and while abroad must have transmuted what they saw into the inwardness of the A La Ronde vision, where they were to lead lives of self-cultivation and self-realization.

18 The design of A La Ronde was supposed in family tradition to reflect the octagonal design of the church of San Vitale at Ravenna, which the Parminters had seen on their travels. There may be some truth in this, but there was also a certain vogue for near-circular buildings at the time, and in 1816 John Lowder junior, the probable architect of A La Ronde, went on to design the 32-sided Bath and District National School in Bath in 1816.10The cousins were presumably attracted to a distinctive appearance, which internally allowed the rooms on each floor to be accessible one from another in an unending circle: if, as seems likely, they were already experimenting with spectacular effects, this capacity may have been seen as an asset. In terms of the analysis of space, this plan produces both a lack of depth in that all rooms are equally at a primary level of access and are therefore hierarchically and democratically equal, while preventing any long, clear line of sight, so creating senses of mystery and surprise.11 The building produced by Jane and Mary did not privilege any personal space dedicated to either or both of the women — there are no individual studies or work rooms — but did permit the exploitation of curiosity and the desire to see. This is in stark contrast to most contemporary and nineteenth century domestic plans in which a hierarchy of access is very apparent and is designed to reinforce the privileged position of the male head of the family. The design of A La Ronde is expressive of a desire to choose for oneself, but embedded within are also statements of equality between the two cousins in a world where notions of equality were very live issues, and the capacity for a hide-and-seek, peep-and-see program of display.

19 Internally, the rooms were created by the women's hard work, in which Jane seems to have taken the lead, and this work featured very prominently the creation of designs, applied to the walls, in feathers and shells, and of picture effects created from seaweed and sand highlighted with various types of mineral glitter. There remains in the Drawing Room four elaborate shell pictures believed to have been brought back from the continental tour, which may have contributed some inspiration. The climax of the decorative scheme was the Shell Gallery in the top section of the house. Shell work of this type was not, of course, the Parminters' invention. A well-established tradition of architectural shell grottoes runs back through the eighteenth century to the Grotto of Thetis, which formed part of the original landscape setting of the palace at Versailles before it was demolished in 1681, and beyond to the rocks and fountain grottoes of the Mannerist artists.12 Similarly, the collecting of shells for both taxonomic and decorative purposes was a part of the beginnings of modernist collecting in the sixteenth century, and by the early eighteenth century decorative shell work had become something of a rage. Pope's "open temple" near his Twickenham villa was finished with shells and pieces of mirror glass, and Lady Walpole, the Prime Minister's wife, had a shell grotto, to name only two of the most prominent participants. The Duchess of Portland, who had an important cabinet of shells, also had a shell "cave" at Buldstrode created during the 1760s. There were well-known and important eighteenth-century shell grottoes at Carne Seat (Goodwood), created by the third Duchess of Richmond, at Clifton near Bristol at Mereworth and (about 1820-30) at Margate on the Kentish coast, where the subterranean grotto in the form of a rectangular cell, was approached by a twisting passage and rotunda.13

20 By the 1800s this tradition had been brought into the remit of bourgeois private domesticity. Women like Mrs Delaney and the Parminters used a range of natural materials, collected in the Parminters' case largely from the beach about two miles below their home, material that in the value judgements pertaining then (and now) would be regarded as rubbish. These objets trouvées were transformed from nature to culture not by incorporation within the taxonomic scheme of a Linnaean-based classificatory system, but through reference to the creation of a "natural" aesthetic in which the satisfaction gained from an exercise of reason in scientific tabulatory control is replaced by the pleasure that derives from a perceived fusion of home and nature in the recreation in the house of a "natural" expression. This relates to the Gothic/Romantic theme of essential object characters positioned powerfully in relation to less-than-commanding human individuals, whose role is to bring together, to arrange "as the material naturally dictates," and to view.

21 Collecting as practice (rather than content of collections) is now receiving a good deal of attention. The Parminter cousins exhibit very clearly a style of collecting practice that, by the later twentieth century, is essentially feminine.14 They accumulated easily-gained and inexpensive material that did not command value in the market place, and then expended much effort upon it to transform it from the outside to the inside of their lives by affective effort that turns it into a valued, emotion-carrying category signifying shared memories and the construction of home. Female collectors, in contrast to males, are broadly categorized by a preference for decorative collected material, which can be placed on show in a style that helps to create the domestic interior, with all that this implies, and which can acquire added value, especially as memory carriers. This is a new domestic form of the consumption of nature where consumption operates as the dynamic interplay between material objects and self and acts to define, reproduce, change and subvert identities through shared aesthetics, styles and meanings. In this, the boundary between "high art" and "craft" becomes blurred for both are visibly capable of making profound statements about the human condition and its relationship to the external world.

22 It is, of course, no accident that the shell and feather craft work undertaken by the Parminters was, and is, viewed as an essentially feminine accomplishment, and as such, like embroidery and knitting, to be considered as a second-class pursuit. Femaleness is at the centre of the Parminter project. The legal arrangements made in relation to the school and almshouses at Point in View, and to A La Ronde itself show that self-conscious feminism was a very important strand in the Parminters' thinking about their establishment and their view of the world. The estate and its style were specifically conceived as a statement of female appropriation. Only during the period of Reichel's ownership was this voice denied. We do not know the detailed personal circumstances in which the heiress to the property, Stella, transferred it to her brother Oswald Reichel, but we do know that he was aged forty-six, had recently retired from a substantial position in the Church of England that will have hitherto provided him with agreeable board and lodging within Cuddesdon College, and almost immediately arranged his domestic needs by marrying Julia Ashenden. It may not be stretching our knowledge too far to suggest Stella may have been under some pressure to sacrifice her own position in the interests of securing to her brother a domestic establishment seen as appropriate to a Victorian clergyman. Be this as it may, Reichel ignored the peculiar properties of the house, and by putting in hand a number of "improvements," did his best to turn it into a normal later-nineteenth-century gentleman's residence. If he had a son, we may surmise, the particular internal character of the house would have gradually been removed, and its peculiarities of design smoothed away by a process of "normalizing" through constructional changes and additions.

The Second Transformation 1973-1991

23 The second transformation at A La Ronde may be discussed more briefly. The descent of A La Ronde from the death of Mary in 1849 through to its acquisition by the National Trust in 1991 points up very well the culture clash shown by transmission through the female line that involves a single blood line of women but four different surnames (Parminter, Herlock, Reichel and Tudor-Perkins), a fact which would obscure the realities unless the matter were pursued in some detail. In this inheritance line, there were moments when the continued existence of the house and (what remained of) its interior was seriously threatened: in 1929 when Julia, Oswald Reichel's widow, put the property on the market, and in 1973 when Ursula Tudor-Perkins inherited.

24 1929 was a poor moment to embark on the ownership of what might be seen as a folly, in poor repair, in a relatively distant part of England, on the part of a maiden lady in reduced circumstances. Yet Margaret Tudor, who only saw the sale advertisement by chance, did not hesitate to purchase, and in 1935 she opened the house to the public. We can only suppose that she was chiefly motivated by pride in the particular family tradition that the house embothed, pride that must surely have seemed perverse to many at the time. In 1973 Ursula was plainly determined to continue the tradition of A La Ronde, but to find contemporary ways of maintaining it. Negotiations with the National Trust15 were, of necessity, relatively lengthy, but in 1991 the Trust bought the house and the remaining grounds with the assistance of a grant from the National Heritage Memorial Fund. The view of heritage that persuaded the Trust to accept A La Ronde revolved around ideas of individuality, and of the intrinsic interest that attaches to individual effort, or indeed eccentricity, a theme that also plays an important role in the construction of Englishness. There is indeed a traditional historical element of value at A La Ronde in that it is the finest surviving example of the Georgian gentlewoman's craft of shell and featherwork, but it is the acknowledgment of an individual's creative intervention that drives the heritage project of the house.

25 At A La Ronde we see the recognition by a premier heritage institution of the value created by dedicated intervention on the part of individuals possessed of a particular desire to transmute their domestic surroundings through a vision of how the external and the natural can be turned into personal home. "Heritage" emerges as the celebration of individual effort, situated within an historic moment when notions about the intrinsic meaning of material culture and its relationship to humans was changing. A La Ronde as we see it now, at the end of the twentieth century, captures this moment as powerfully as it is possible to do.

Conclusion

26 A La Ronde is the site of an interrelated series of moments where individuals have intervened to create material agendas productive firstly of early nineteenth century notions of the female self in relation to family, society, nature and the act of domestic artistic creation; and secondly of late twentieth-century notions of personal authenticity, of the consumption of other people's lives, and of public display as managed tactfully by a prestigious national body. At A La Ronde we see heritage created through the transformation of private, domestic female eccentricity to public, high-status National Trust exhibition. Heritage and its consumption emerges as the dynamic interplay between material history and people, which acts to create, subvert or change identities through its construction of aesthetic and meaning.

APPENDIX A

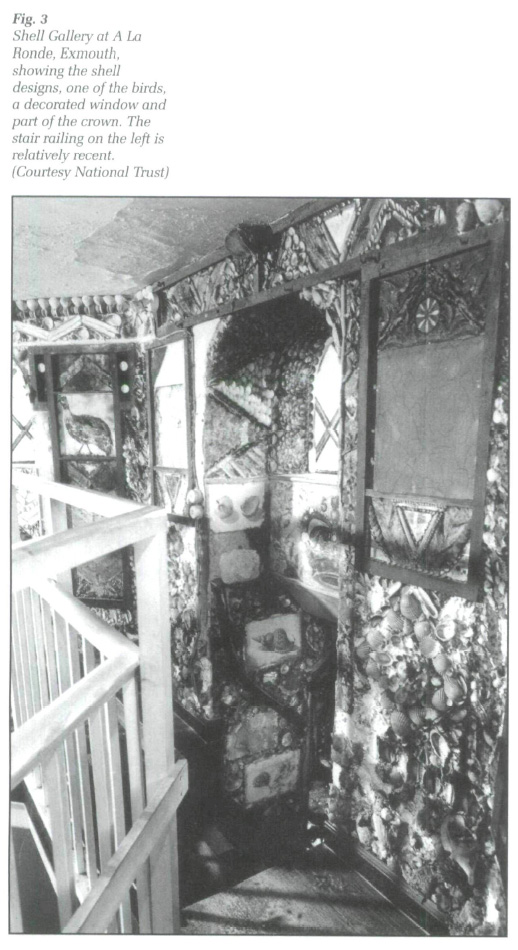

27 Jane was born in 1750, and Mary in 1767. They were, in fact, first cousins once removed, as the table below makes clear. Owners of A La Ronde are in capitals. Information relating to this genealogy will be found in Meller (1993) and Tudor-Perkins (see note 2).

I would like to thank the staff at the National Trust East Devon office, especially Hugh Meller, for the help that has been given to me. Thanks go also to staff at the West Country Stuthes Library, Exeter and the Devon Record Office, Exeter.