Pictures and Portraits / Images et Portraits

"You Paint Me a Ship as is Like a Ship":

The Verkin Ship Portraits

Abstract

Commercial maritime photography archives are rich, largely underutilized, resources and examining photographs from them within the context of the history of ship portraiture offers another way of understanding these collections. Images from the Verkin Studio archive from Galveston, Texas, because of their subject matter and adherence to specific representational conventions, maybe viewed as a step in the evolution of ship portraiture. Ship portraits appealed to owners, captains, officers, and crew members alike, and from the eighteenth century onward, a diverse clientele was supplied by craftsmen of varying skill. By the twentieth century, the creation of these pictures using a camera — while maintaining the visual conventions and centuries-old practices of manufacture and sale — testifies to continuity in the craft of ship portraiture. Photography, the quick and relatively inexpensive way to obtain representations from life, supplants the quick and inexpensive pierhead painter.

Résumé

Les archives photographiques de la marine marchande constituent une réserve fabuleuse, mais fort peu exploitée, et l'examen des clichés qu'elles renferment dans le contexte historique des reproductions artistiques de navires jette une lumière nouvelle sur les collections de ce genre. On peut considérer les images tirées des archives du studio Verkin, à Galveston (Texas), comme une étape dans l'évolution des reproductions artistiques de navires, en raison de leur thème et de leur respect de normes de représentation très précises. Les portraits de navires plaisaient aux affréteurs, aux capitaines, aux officiers et aux membres d'équipages. Dès le XVIIIe siècle, des artistes au talent variable s'efforcèrent de satisfaire une clientèle diversifiée. Au XXe siècle, la création de telles images par le truchement d'un appareil photo — sans déroger aux conventions visuelles ni aux pratiques séculaires de la fabrication et de la vente — démontre la continuité de l'art de la reproduction artistique des navires. La photographie, méthode rapide et relativement peu coûteuse de représenter la réalité, supplantera donc rapidement l'artiste-peintre, qui exécutait un tableau en deux temps trois mouvements pour quelques sous sur les quais.

1 When the English poet C. Fox Smith wrote a poem called Pictures she wanted to explain to the landlocked what it was that sailors sought in paintings of ships. Her protagonist, Bill, tells his audience,

an' some likes 'orses best

...But I likes pictures 'o ships...an' you can keep the rest

...An' I don't care if it's North or South, the Trades or the China Sea

Shortened down or everything set — close-hauled or runnin' free

You paint me a ship as is like a ship...an' that'll do for me.1

Ship portraiture — the accurate painting of important or significant vessels for owners, captains, or crews — was a kind of representation practiced in port cities for centuries. Since accurate representation was the most highly prized attribute of ship paintings, photography would seem to have been the perfect medium for creating a visual record of ships and shipping, and photographers familiar with waterfronts to have been the logical successors to legions of "pierhead painters." Maritime museum photography collections abound in representations of ships and shipping, and this essay explores another way of understanding the rich visual material housed in what usually function as research and reference collections.

2 Members of the Verkin family of commercial photographers who practiced in the port city of Galveston, Texas, produced a valuable, very traditional collection of ship portraits. They loved ships. Both Paul Verkin and his son, Paul Roland Verkin, spent hours on the docks and piers of Galveston taking photographs of the vessels that called there. An extensive documentary record of watercraft that were active in the port was the primary fruit of these endeavours — some images created in the regular course of work for the Galveston Wharf Company or other clients, some taken because the Verkins were intrigued by a particularly unique vessel, and a significant number of the pictures shot "on spec," taken, developed, and printed to be sold to the ship's officers and crew as they disem-barked in the island city. They were craftsmen, as John Szarkowski notes, "whose professional lives were defined in terms of service to specific communities — geographical or cultural — that no longer exist," part of "the last generation of professional photographers who practised their trade as a local cottage industry." 2 In making these images and marketing them in this specific way, the Verkins not only created an invaluable collection of ship pictures but also perpetuated the centuries-old practice of ship portraiture.

3 This essay is part of a longer manuscript mat examines the maritime photography of the Verkin family. Originally, thirty-one images were examined in the context of a discussion of photographic ship portraiture, some pictures chosen as the best representations of traditional composition and practice and others selected as evidence of the incorporation of photographic technology into the creation of ship pictures. Paul Verkin, who began taking pictures at the port of Galveston in the 1880s, advertised himself as a "commercial photographer" or "view photographer" and worked out of his home or office. Not until his sons also began working as photographers did the Verkins open a "studio." The eight photographs analysed here are only a representative sampling of the more than three thousand negatives that survive and an even lesser percentage of the thousands of negatives created by the photographers over their time in business.3 These particular images were selected because of the style of their presentation and their relevance to a discussion of ship portraiture. Both in their circumstances of production and appearance, the pictures testify to the perpetuation of the practice of ship portraiture through the modern medium of photography. To the extent that photographs might be less expensive to produce than a painting, this practice even expanded the market of consumers who could afford to purchase photographic images of ships.

4 As a major port on the Gulf of Mexico, Galveston welcomed a steady stream of vessels, especially in the years that the port dominated cotton carriage. Even as late as 1936, forty-five steamship lines served the city, with forty-two of them offering regular foreign service and three working coastal routes.4 In addition, craft moving goods through the intra-coastal canal (constructed during the operation of the Verkin Studio) and numerous local vessels called in the port for one reason or another. If the archive is any indication, the Verkins never lacked for subject matter.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

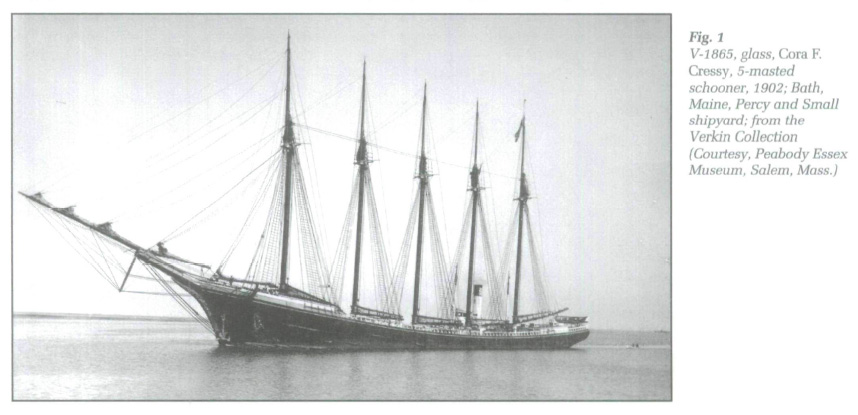

Display large image of Figure 35 The eight ships considered below were selected for their pertinence to this particular discussion of ship portraiture. Exact dating of the images is impossible, but information in the collection's index notes that the identified vessels in the photographs were built between the years 1891 and 1927.5 Three of the pictures were printed from glass negatives and five from nitrate film stock. Cora F. Cressy (V-1865) (Fig. 1) Concho (V-44) (Fig. 2) and Britannia (V-1749) (Fig. 3) appear to have been equipped with sailing capability. The remaining ships are more modern powered cargo carriers. Clearly, a diverse fleet might be in port at any given time, and ships of the most advanced technology might berth near the most basic of sailing vessels while all were tended by specialized local craft providing necessary port services. At this time, the needs of maritime commerce created profitable niches for many different kinds of ships.

6 What vessels, then, are chronicled? Much may be gleaned by close examination of the photographs. The easiest way to identify a ship is by simply reading the name on the bow. Where this is impossible, those familiar with steamship companies may determine a ship's identity from distinctive insignia on her smoke stacks or from house flags flown on board; a national flag indicates a ship's country of registry. Concho (V-44) (Fig. 2) represents one of the most important clients of the Port of Galveston. The ship is "dressed," flying signal flags in celebration of arrival or departure — or simply in honor of having a picture taken. Also included among the passenger ships is the Iroquois (V-1667) (Fig. 4), a beautiful liner built in 1927. Both ships are pictured postcard style — broadside, steaming through the water with stacks smoking as they make their way down channel. Unlike the photograph of Iroquois, there is no local shrimping vessel in attendance to suggest scale or speed of Concho; the passenger ship steams sleekly along, the hull form slicing across the heavy, almost equally sized horizontal areas of sky and sea that seem to sandwich the ship in the centre of the image. A small bow wave and smoke direction suggest forward progress, and the wave action in the foreground sweeps the eye toward the stem of the ship, adding to the impression of movement.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

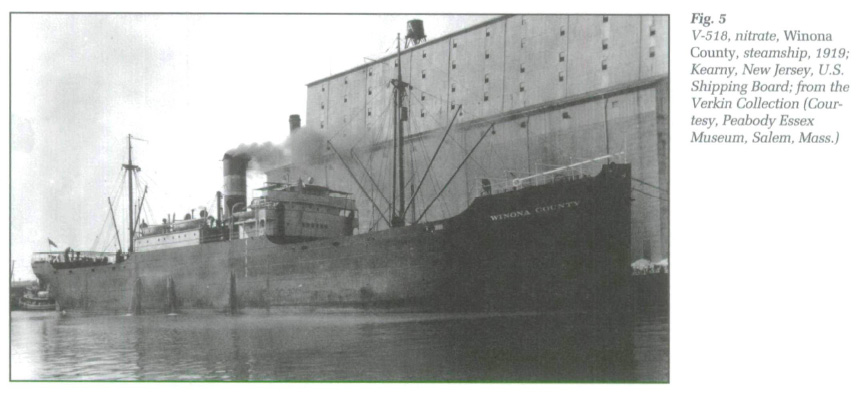

Display large image of Figure 57 The port moved more freight than passengers, and other images under review portray the kinds of vessels employed in this work. As if to suggest the loading and unloading of cargo, the Winona County (V-518) (Fig. 5) is pictured at the dock, photographed from a pier opposite the vessel. The ship is high in the water, awaiting loading or with a cargo recently discharged. Such craft could probably carry a few passengers but were not designed or equipped for the hundreds that could be accommodated on a passenger liner. Winona County was also a U.S. Shipping Board vessel and is shown berthed alongside one of Galveston's grain elevators. The ship is getting up steam, smoke streaming from her stack and engine cooling water being discharged over the side. She may be moving into position prior to loading. The photographer looks up at the pier-side vessel, in a manner different from traditional ship portraiture. It is quite possible that this image was taken to promote the facilities of the port of Galveston, or that one of the Verkins, on the wharf for some other business, took the picture out of personal interest.6 Nevertheless, the ship is depicted as a strong, impressive object. It stretches across the frame, the rise of the bow working against straight lines of the horizon, conveying lift and power. Perhaps the most unusual vessel included is the Britannia (V-1749) (Fig. 3), a whale-back barge equipped with sails. Built in West Superior, Wisconsin, she was probably constructed for the Great Lakes; records indicate that by 1927 she was owned by Sabine Towing and Transport Company, a firm based in Port Arthur, Texas, which might explain her presence in Galveston.

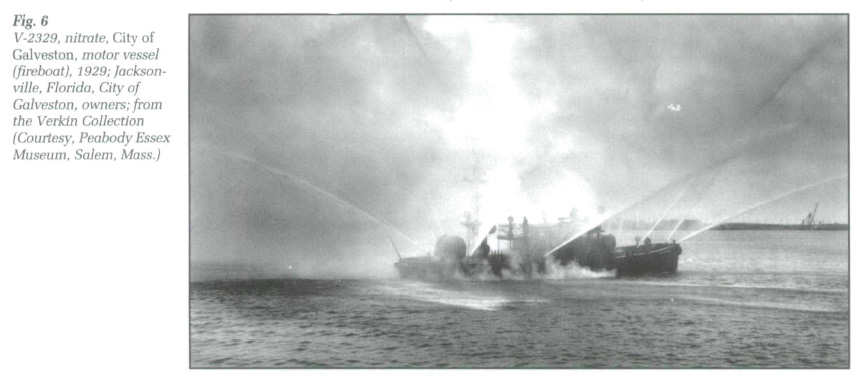

8 Also included in this sampling are watercraft important to the operation of the port. The diesel-powered City of Galveston (V-2329) (Fig. 6) was built in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1929 and purchased by the city for fire protection along the waterfront. The steel motor vessel was 87 feet (26.5 metres) long and 18.6 feet (5.7 metres) wide with a mean draft of 6 feet (1.8 m). She was powered by a 250-horsepower engine, but saved her real power for the pumps.7 In 1931 the Wharf Company proudly claimed that the "craft makes use of the latest features and attains a speed of 12 knots per hour" and went on to assure clients "she is docked near the center of the waterfront, at Pier 23, and can quickly reach trouble at any quarter of the wharves." Two crews were available for round-the-clock availability and her two 500-horsepower engines were capable of pumping 7,500 gallons (28 000 litres) of water per minute.8 The fireboat was a prized possession, owned by the city and manned by the fire department. The Wharf Company repeatedly cited the vessel's "instantaneous response," her capacity "to respond at an instant's notice," and the fact that she "has always been ready."9 While stressing the fireboat's preparedness, the Wharf Company reassured its audience that "the fireboat has not been called upon to play any spectacular role at a big fire." This particular picture captures City of Galveston in the channel off her regular station as she demonstrates her capacity — on a variety of trajectories — in a major display of fire fighting hubris.

9 Naval vessels were also frequent callers to the port, and Verkin captured many of the visitors on film. In this sampling, U.S. forces are represented by the light cruiser, U.S.S. Memphis (V-1692) (Fig. 7). The U.S.S. Memphis has a modern appearance, her masts devoted to communication and observation equipment rather than sails. The image of the Memphis, printed from a glass plate negative, has the name of the vessel engraved directly upon the negative, suggesting that the picture was mass produced for sale during the ship's visit.10

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 710 One of the most striking pictures captures a large sailing vessel that called in the port. This schooner, the Cora F Cressy (V-1865) (Fig. 1) was built in Maine in 1902 and could still operate profitably despite the prevalence of steam vessels. She most likely brought general cargo and worked as a tramp carrier, finding and loading whatever needed to be carried. Upon unloading in the next port, the routine of securing another cargo began again. The picture of this large schooner suggests some of the limitations of photography in ship portraiture. Unlike a painting, photographic images of schooners in port portray the ships as they actually appeared at the time the image was taken. Sails are furled, and the ship lays at anchor. Where an artist could create an imaginative composition with all sail set and the vessel underway, a photographer shoots what is before the lens.

11 The Galveston Wharf Company was a regular client of the Verkin Studio. Pictures of ships that were taken by the firm may be found in port promotional materials, annual reports, and employee publications. In addition, other community organizations used ship pictures from the Verkins as part of general island publicity.11 Besides taking pictures of ships for these local interests, Verkin Studio photographers — frequently one of the Verkins — would photograph ships as they sailed or steamed up the channel prior to docking or as they were eased into a berth on the Galveston waterfront. After securing the desired image, the photographer would hurry back to the studio (located very near the most active part of the wharves), develop the film, and make prints of the best pictures. Later, prints in hand, Verkin or one of his employees would offer the images for sale to the officers and crew. Conversations with Verkin descendants and collector Eric Steinfeldt confirm this practice.12 This process — the rapid creation of a ship's portrait in port for sale to her crew — was a custom that originated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A particular kind of itinerant artist who lived near the waterfronts of England and Europe specialized in sketching and painting newly arrived ships and then offering their works to the ship's crew. Owners or captains could commission expensive oil paintings of a favourite ship, and regular crew members often were no less proud of their respective vessels. A small, inexpensive, and quickly executed painting on a board or piece of fabric could be a prized possession at the end of a voyage. These renderings — ship portraits — are a special kind of image with a distinctive art historical pedigree.

12 Within the field of art history, ship portraiture is generally considered to be a subset of marine painting. Marine painting, in turn, is traditionally understood to be a kind of landscape painting. In American Marine Painting, John Wilmerding argues that "marine painting belongs on an equal level of related, coherent interest [to landscape painting]. Often the two areas run parallel to each other: seldom is one an integral part of the other. We have cousins here, or brothers perhaps, but not parent and child."13 Within the category of marine painting may be depictions of anything sea-related, including seascapes, shoreside scenes of fishermen or busy ports, commemorative views of famous battles, launchings or embarkations, and ship portraits. What distinguishes ship portraits, however, is the overriding commitment to the accuracy of the representation. With roots that are equal parts drafting in nature as well as artistic, the ship portrait is a hybrid product of excellent drawing and deliberate style. The best of ship portraits, magnificently executed renderings in oil on canvas, were above all documentary art and not fine art in the tradition of marine artists like J. M. W. Turner or Fitz Hugh Lane. The Verkins, in producing their ship images, represent the next in a long succession of ship portraitists, following a path trod by artists since the seventeenth century.

13 Views of ships within larger works may of course also be found in ancient Egyptian and Greek art.14 As the sea became a more important factor in human activities, visual materials and representations included more and more water-related images. Homer's Iliad and Odyssey both concern sea voyages and representations of these epics naturally include depictions of ships. The story of Noah and the flood and various biblical references to fishing were maritime subjects that were incorporated into religious art. Boats and ships also carried symbolic weight in particular visual contexts as well. Ships appeared on the seals of maritime cities as early as the twelfth century and are "surprisingly accurate" in rendering vessels later recovered or understood through other means.15 In portraits of prominent individuals, ships were frequently incorporated in the background as signifiers of wealth, victory, or extensive travel in a painting of a nobleman, naval officer, or wealthy merchant.

14 European voyages of exploration also provided subject matter for a wide variety of representations that commemorated discovery, conquest, and European expansion. Notable marine imagery documents the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, depictions that fuelled a long British tradition of painting naval battle scenes.16 In addition, increases in both the complexity of ship construction and the size of vessels meant that more and more drawings were created to guide the shipbuilder. An English shipwright, Matthew Baker, wrote and illustrated the manuscript, Elements of Shipwrightery, circa 1585.17 The drawings from this work are technical in nature, seeking to convey by accurate mechanical representation the correct dimensions, proportions, and orientation of ships of the period. In short, by the sixteenth century, marine painting, in technique and in the treatment of its subject matter, became a respected genre in its own right.

15 The rise of Dutch shipping, the increasing wealth of that region, and political struggles for independence brought with them an attendant growth in consumption and commemorative art for an expanding class of affluent merchants and financiers. Prosperous individuals commissioned or purchased visual records of their wealth (ships) or of their regional strengths (ships and shipping). Three particular phases in Dutch marine painting lifted that kind of representation to new technical and aesthetic levels and established the field as a distinct artistic form. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, artists concentrated on painting pivotal engagements at sea that led to Dutch independence from Spain. In addition, pictures of busy port scenes and voyages of exploration documented and celebrated commercial expansion and economic growth. During the second, subsequent phase of Dutch marine painting, practitioners focused more on the natural context of vessels, concentrating on sea, sky, and the depiction of wind and weather. The third and final phase of this distinctive art form saw a return to naval battles during the Anglo-Dutch wars.18

16 Ship portraits are generally evaluated by different standards than those usually applied to history paintings or even landscapes. As mentioned earlier, to be taken seriously by a maritime audience in a nation proud of its naval supremacy, paintings had to depict ships accurately. The correct number of masts, proper rigging, appropriate sail configurations, and a realistic attitude of a ship in the water were crucial, whether portraying a pivotal naval battle or the most mundane of waterborne commerce. The great advancement of the Dutch marine artists was in painting ships that "looked right." Willem van de Velde the Elder (1611-1693) and his son, Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633-1707), are the most prominent and important marine painters of this period, not only for their combination of technique, accurate representation, and innovative subject treatments but also because they moved to England in the early 1670s where they received royal patronage. Once in England, they continued to focus on marine painting and achieved great success. After 1674 each was paid a salary of £100 a year by Charles II and later James II to make drawings of sea battles and convert the renderings to paintings.19 This patronage resulted in the creation of a massive documentary record of watercraft from the period and in the establishment of a school of British marine artists.20

17 British support of marine painting and the availability of subject matter in the expanding and thriving English ports led marine artists to settle around active waterfronts. The presence and success of the Van de Veldes encouraged numerous lesser painters, and markets for marine representations grew. Not only did the British aristocracy commission paintings but a healthy demand for ship portraits arose from large communities of merchants and seamen that could be found in the port cities. And the artists in the lower social and economic strata of these urban areas could seldom support themselves from their ship paintings alone. Frequently, ship portrait painters paid the rent as draftsmen, house painters, ships' painters, or carvers of figureheads or other kinds of ship ornamentation.21 In addition, sea cadets learned drafting skills, and chart-making and coastal sketches were often expected from navigation officers in the navy and merchant marine. Changes in ship construction led to the professionalization of naval architecture; ship plans required more exact and exacting drawing skills, abilities that some craftsmen transferred to the creation of ship portraits.22 Upon retirement, men with maritime careers, guided by their familiarity with ships and the sea, sometimes settled in waterfront areas and commenced producing ship portraits. Only a modern appreciation of primitive or naive art has ultimately granted these practitioners any attention in the fine arts world.

18 Painters of ships' portraits, then, emerged from two strains of artistic lineage. On the one hand, schools of highly trained, mostly landscape, artists supported by public commission, aristocratic, or mercantile patronage created works depicting important maritime events or special vessels for the public sphere or the wealthy, whose financial success increasingly derived from things maritime. On the other hand, self-trained artisans speedily produced paintings for officers and crews of these ships, individuals more intimately engaged in the daily routine of maritime commerce and pressed for time but no less desirous of visual renderings of their equally esteemed commands or homes. An officer returning from a long overseas voyage could claim no better souvenir than a portrait of his command, rendered in a foreign port and bearing the signature of a foreign artist.23 As Basil Greenhill has noted, "most masters and owners of small vessels could not afford the famous, but relied instead on a breed of artisan painter, a breed which grew up in the ports by demand, who for a small sum would produce a ship portrait, sometimes overnight."24 "This sort of picture [ship portraits] owed as much if not more to the draughts and doodles of mariners, shipwrights and others of maritime calling...embracing the plebeian as well as the patrician."25

19 By the first quarter of the nineteenth century, shipowners, shipbuilders, and captains frequently commissioned portraits of merchant ships; occasionally an owner would order a single view of his entire fleet. George Mears (fl. 1870-1895) was "official marine artist to the London, Brighton, and South Coast railway" and painted representations of all the cross-channel steamships operated by that company.26 The period from 1870 to 1914 was the glorious zenith of British commercial sea power. During the 1870s and 1880s, British shipowners built upon their dominant position and found employment for their ships all over the world. Huge sailing ships and powerful steam vessels traveled the world's oceans and passed each other from port to port. By 1900, tonnage registered in Great Britain equaled almost half of all the tonnage in the world and by 1914 British ships would carry half the total sea trade of the world.27 Demand for ship portraits, pushed by the numbers of men working in the industry, expanded with the trade, and most ports developed enclaves of pierhead painters who catered to the myriad sailors in any given port.28 Reuben Chappell (1870-1940), one of these painters who later gained professional respect for his portraits, "painted, on the spot, hundreds of vessels which represented the last days of sail" and "was prolific..as his livelihood depended on the few shillings which seafarers could afford in order to buy his pictures from him."29

20 Other new kinds of enterprises increased the demand for ship portraits. Competition between steam and sail passenger lines meant more aggressive advertising for travelers and shippers. Broadsheets listed sailing times for the most modern, luxurious, and regular of passenger services and would often be embellished with portraits of the vessels, thereby providing visual evidence of a company's claims. Local tradesmen also took advantage of a vessel's visual appeal; "R. Crag Sailmaker Swansea" appears on the sails in a watercolour painting of the Swansea pilot schooner, Lion, implying that sails good enough for the pilots would be equally splendid for other craft.30 Besides private commissions and advertising uses, images of ships found their ways into the numerous new illustrated daily and weekly newspapers which, by the mid- to late-nineteenth century, felt obligated to provide their readers with visual representations of important stories. Beginning with the Crimean War, marine artists were sent to cover naval events pertaining to the conflict. They provided the illustrated press with sketches and drawings that could be reproduced to supplement correspondents' reports.31 By this time, marine artists also made lithographs from particularly successful marine representations for sale to the general public.32 An additional market arose from the production of postcards by local photographers for sale to residents of visitors to coastal towns or to passengers aboard the various ships.33

21 Ship portraits, however, no matter what their use, meet certain criteria and may observe particular conventions. "A ship portrait is a drawn or painted record of aspects of a particular vessel. It may exist in its own right or be a component of a composition portraying some happening or place, a naval action or port scene ...The subject may be glorified, flattered, made fun of or treated in any other way. It is a portrait so long as it declares the identity of its subject.34 As mentioned above, accuracy was prized above all; but that did not necessarily mean a strictly realistic vision. Customers might request the exaggeration of certain details, "the flags — standards, ensigns, pennants, jacks, burgees, signals and demonstrations of nationality, ownership and identification...In some portraits the direction in which they [flags] blow was governed not so much by wind as by readability, and a flag flying in an unrealistic direction is rarely an artist's 'mistake.' Flags mattered a great deal to the client — a master who was a Freemason would require his square-and-compass symbol flown..."35

22 The more professional artists often used models to guarantee accuracy, sometimes keeping many ships built to scale — or pieces of ships — to use for their paintings. Artist J. C. Schetky wrote to Admiral George White imploring that White's sailmaker make and fit "in all particulars of gear — a fore-sail, fore-top-sail, and fore-top-gallant sail...for a frigate...I have all masts, yards and rigging, complete and beautiful, but can't get the sails ship-shape... You will perceive at once my object and desire to have this model — it is to place it on my lawn and draw from it, for there are no mast-heads to be seen here at Croydon; and I am much at a loss for details when my ships come large in the foreground."36 On the other hand, the so-called pierhead painters were frequently self-taught by years at sea or observed vessels in the ports where they lived.

23 The most basic and least skilled portraits often strove for delineation only, with a lettered inscription "across the base of the composition recording perhaps in elegant copperplate the rig, ship name, port of registry, and name of commander. When drawn on light or dark base, it [the inscription] served to direct the viewer's gaze into the picture...Where this device was not used the foreground was often represented as in shade cast by a cloud — a compositional ploy used again and again by the best practitioners.37 The ship was also presented in a very stylized fashion, usually broadside. In the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, showing a vessel in three different views within the same picture became popular. In addition to the most common broadside view, the same ship would be painted "sailing off to port and starboard."38 For more money, a stern or bow view of the same ship could be added to the composition. "The more that went into the picture, the larger it was, the costlier."39 Whether the image was produced in oil or watercolour could affect price as well, with waterbased pictures being the less expensive. Vessels were often positioned near a familiar point of land to commemorate a particular voyage or an especially fast passage, and the work might be inscribed with the name of the craft and date of landfall. Sometimes clients requested ships depicted under particular circumstances — in a gale off Cape Horn, for example, or engaged in a rescue or altercation with pirates.

24 In general, "the most elaborate works...were for naval officers and ship owners, the middling ones for the commanders of ocean-going merchantmen, the smaller shipbuilders and ship-brokers, the simplest for the masters, mates and lesser crew of coasting vessels."40 This hierarchy of production illustrates both the size and variety of the ship portrait market. Ship portraiture style remained rigid and circumscribed until the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century, largely because the men who purchased the images were intensely traditional themselves.

25 Surprisingly, given the stress upon accuracy demanded by purchasers of ship portraits, the use of photography in creating these images was slow in coming. By the mid-nineteenth century, some ship portraitists were using photographs to aid the production of their paintings, but photography did not replace painting by any means.41 Technological limitations were largely to blame, since the size of the equipment and long shutter speeds made it difficult to shoot objects that were constantly moving through the water or bobbing at anchor. Even vessels secured to a dock bob up and down according to tide or current, and early marine photographs are often blurred. With advances in technology, more convenient cameras and faster lenses made good pictures of vessels possible, and some marine artists eventually used photographic images from which to paint.42 And, as in the case of the Verkin Studio, some commercial photographers in port cities assumed the roles and the markets of lower end ship portrait painters.

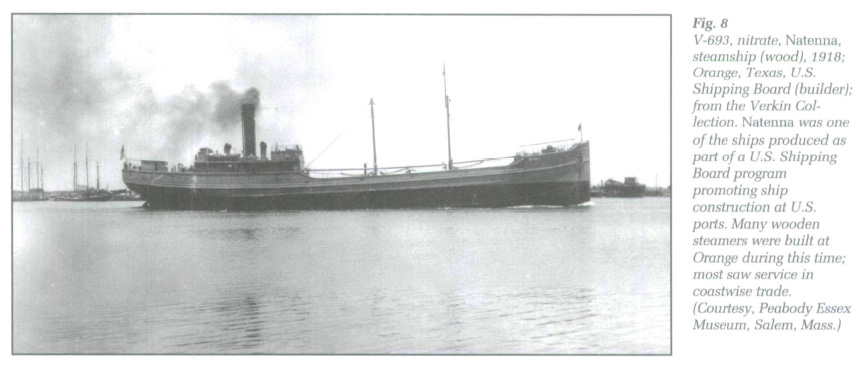

26 Looking at the sampling of ship images from the perspective of the history of ship portraiture offers another way of understanding these representations. The Verkin photographs follow ship portraiture convention in a number of important ways, but at the same time introduce both the limitations and possibilities afforded by photography. Like many paintings, most of the images are captured near familiar land areas. All of the pictures were taken either in the Galveston channel or berthed at one of the wharves. Familiar land structures may be seen in the background — storage tanks and buildings on Pelican Island (V-693) (Fig. 8) or Wharf properties (V-518) (Fig. 5). The channel itself is very distinctive, a long, narrow stretch of water bordered near the commercial wharves by jetties to the south and Pelican Island to the north. While this attribute is indeed a convention of ship portraiture, Galveston channel geography also facilitated capturing the vessel underway, most often broadside, another traditional aspect of ship depiction. In fact, the topography of the channel and location of the port created a uniquely propitious setting for the creation of photographic ship portraits. Every vessel visiting Galveston passes through the constricting waterway. The narrowness of the channel helped Verkin obtain clear, relatively close views of the watercraft that passed nearby thereby appropriately fixing the vessel and its location in the representation. Without elaborate special effects, largely unavailable at this time, or rendered impractical by cost and time requirements, photographic ship portraitists had fewer options in situating their subjects; marine artists positioned painted ships within familiar landscapes at the client's request. The Verkins had little other recourse, but this coincidence of photographed and painted ship portraits worked to keep filmed portraiture within the parameters of painted representation.

27 Besides locating their subjects in a comparable way, artists and photographers also represented the vessels quite similarly. All of the images are horizontal. Rather than emphasize the height of masts or stacks, both kinds of portraitists focus on the length of the vessel as it extends through the water. All of the images considered here show vessels broadside, also the most common point of view for ship portraits. The generally straight orientation of the pictures is made more noticeable by the strongly linear components of the images themselves — the horizon line, the length of the ship's hull form, the wave shadows on the water. Many of the ships seem to be composed of layers of lines, with parallel levels of rails, decks, awnings, or portholes, and even smoke spewing from stacks trails away in linear fashion. Vertical masts or stacks and diagonals of rigging are the only punctuation in the sweep of a hull. Motion is suggested but not apparent, conveyed by wakes, discharging smoke, or small bow waves. (Channel traffic is generally restricted to a very slow rate of speed and a captain whose vessel was having its picture taken would probably cut his speed even further.) Marine photographers, like the Verkins, were familiar with traditional marine representations. They met with and dealt daily with sailors, officers, shipping executives, and wharf company representatives who possessed painted ship portraits and were used to seeing ships portrayed — in newspapers and publications — in very traditional ways. As commercial photographers, the studio was not hired to create innovative or pathbreaking imagery; ship photographs were meant to conform to long established standards and conventions of ship paintings.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 828 Moreover, representing a vessel broadside eliminates perspective and lessens any sense of depth or movement within the image that might be conveyed. A ship shown broadside appears to move cleanly across an image, entering and exiting the frame independently of the observer and conveying freedom, speed, intent, and unfettered progress. Where ships are captured in perspective, their sense of motion is more strongly suggested, but the observer is a more active participant. An added benefit to the photographer with less than perfect equipment was the opportunity for a longer shutter speed when capturing an image that was far away. Taking a picture of closely and rapidly approaching watercraft had less margin for error than shooting at greater distance. The ship either moves away or toward the viewer, implying an interaction or even interference, a stopping or starting. The frame of the image may be confining or directing; no longer does the ship simply move past and beyond. Perspective may make a ship appear more real, but reality is not necessarily the primary intended impression. Ships carry imaginative freight as well as goods and people, and those most desirous of ship portraits prize both the realistic depiction of the vessel and its implied journey, a voyage that might be constrained by an image too literal in its appearance.

29 The naval vessel U.S.S. Memphis (V-1692) (Fig. 7), slightly angled within the frame, gives a suggestion of movement, although calm waters and no wake work against such a perception. What makes the ship appear to be moving has more to do with the large white cloud area in the left side of the sky, with the way the top of two cloud banks recede almost exactly parallel to the tops of the communications masts and their wires, and with the large white hull of the ship and its reflection in the water on the left side of the picture. The composition of clouds, ship, and water, as well as the slanting to the right of the identification in the lower right of the frame, focus the eye on the left side of the image and move it swiftly down and to the right, following the ship's hull further back into the view. A painter depicting a ship on the open ocean operated under far fewer constraints than a photographer limited by equipment and location. Gains in accuracy were eroded by losses in vivid visualization.

30 In contrast, several of the ship pictures in this sample were taken of vessels as they lay at their respective berths (Britannia V-1749 (Fig. 3), Winona County V-518 (Fig. 5)). As mentioned earlier, these images were likely to have been used in port promotional materials, and do not fit the traditional categories of ship portraiture. The beauty and glory of ships is best depicted underway, and those commissioning or purchasing ship portraits wanted the vessels to be shown actively engaged in their trade. A ship tied to the wharf might be a strong, stable component within a clear, informative composition, but the ship is competing with equally strong, if not larger, shoreside objects. And the focus of activity immediately shifts to the grain elevator, warehouse, or pier, since the ship is purposely attached to the structure for some reason. Wharves and piers connecting the ship to the land worked against the idea of ships as independent, unfettered ocean vehicles. A ship tied to a pier is a passive structure being acted upon, and the craft appears to lose its capacity for agency. While these kinds of images may reinforce the ties of ship portraiture to the larger field of landscape views, these photographs are industrial landscapes, not ship portraits.

31 Photographic ship portraits, because of their subject matter and adherence to particulars of representational convention, may be understood as a step in the evolution of ship portraiture. The creation of these pictures, for the most part utilizing visual conventions and centuries-old practices of production and sale, points to continuity in the craft of ship portraiture whereby photography — the quick and relatively inexpensive way to obtain representations from life — supplants the quick and inexpensive pierhead painter. Given the high value attached to accurate representation in ship portraiture, using photography to generate these kinds of images is a natural development in the larger history of the genre.

32 What is not addressed in this essay, largely due to constraints of time and space, is the reciprocal influence that photography has had on the larger tradition. The painting of ship portraits continued, but those representations assumed certain aspects of photographic technique, most noticeably in the areas of composition and point of view. A survey of later, twentieth-century ship paintings with an eye toward this visual cross-pollination is the logical next step in exploring the evolution of ship portraiture.