Pictures and Portraits / Images et Portraits

Emotion as Document:

Death and Dying in the Second World War Art of Jack Nichols

Abstract

The paintings, drawings and watercolours of Canada's Second World War art collection are a source of contemporary technical, social and cultural data. Some of the more than 5000 works in the collection also provide the evidence of the human emotions experienced in wartime, particularly when servicemen were brought face to face with terrible sights. This is a significant and hitherto unexplored aspect of the war art collection. This paper will explore the Canadian war art collections with particular reference to the work of naval artist Jack Nichols. Although Nichols' work lacks detail and clarity, it provides the more truthful experience of wartime life at sea. Unlike many of Canada's Second World War art works, Nichols's works address death and its surrounding emotions. As such, his compositions are invaluable tools to expand our understanding of the naval servicemen's experience.

Résumé

Les peintures, les croquis et les aquarelles de la collection du Canada sur la Seconde Guerre mondiale forment une véritable banque de données techniques, sociales et culturelles contemporaines. Une partie des 5 000 œuvres et plus constituant la collection laisse transparaître les sentiments que l'on peut éprouver en temps de guerre, notamment lorsqu'on se retrouve subitement devant une scène atroce. Il s'agit d'un aspect important, mais peu connu, de la collection d'œuvres sur la guerre. Cet article fait un survol des collections du Canada d'œuvres d'art sur la guerre, s'attardant aux travaux de l'artiste Jack Nichols, sur la marine au temps de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Quoiqu 'ils manquent de précision et de netteté, ses tableaux évoquent avec le plus de véracité ce qu 'est la vie en mer par temps de guerre. À la différence de nombreuses œuvres canadiennes illustrant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, les œuvres de Nichols gravitent autour de la mort et des émotions qu 'elle provoque. Aussi, les créations de l'artiste constituent-elles des aides inestimables pour comprendre l'expérience vécue par les membres de la marine durant la guerre.

1 Over recent years the study of art has expanded. Art history and art theory have predominated, but it has also become more common to use paintings and drawings as historical evidence, especially in the field of cultural history. A study of contemporary paintings can yield a rich store of information on the life styles, value systems and social attitudes of a particular era. In Canadian art, for example, a number of studies have focused on depictions of the landscape and of native people and, as a result, have expanded our understanding of social and cultural attitudes in particular time periods.1

2 Our understanding of the experience of war can also be explored through art. In terms of the First World War, Maria Tippett's pioneering research on its war art program cast light on a variety of cultural agendas, ranging from the purely artistic to the political.2 Jonathan Vance's recent book, Death So Noble, contributes important insights on the cultural imperatives that determined how Canada would remember this conflict.3

3 Canada's Second World War official art collection also provides a unique opportunity to study a group of paintings, drawings and watercolours as a source of contemporary technical, social and cultural data. The history of the program that generated this art collection has been briefly reviewed in Joan Murray's ground-breaking catalogue, Canadian Artists of the Second World War.4 A small selection of the art has also been discussed from a Marxist perspective in Barry Lord's volume, The History of Painting in Canada: Towards a People's Art.5

4 The fact remains, however, that the intent of the Canadian War Records program, which commissioned war artists after it was established in early 1943, was clearly that the artworks produced constitute useful historical documents in reference to the materiel, personalities and events of that war. Indeed, many of the Canadian artists invited to become Official War Artists in the three services were issued with instructions that placed an emphasis on depicting the machinery, people and events of war accurately. The instructions issued by the army and prepared by Colonel A. Fortescue Duguid, Director of the Army Historical Section, stated: "Any instruments, machines, equipment, weapons, or clothing which appeared in the work had to be authentic."6

5 However, a number of the more than 5000 works of art that comprise the Second World War art collection in the Canadian War Museum also provide another form of evidence — the evidence of the human emotions experienced in wartime, particularly when servicemen were brought face to face with terrible sights and conditions that are both frequent and concomitant to the waging of modern war. War artists not only painted the technical aspects of what they saw but also, in several cases, sought to capture the human side of war as expressed in the intangible emotions of fear, joy, pain and struggle. In such instances the artist functioned as both participant and viewer, and consequently was in the unique position of being able to record not only what he observed, but also what he felt.

6 The fact that the Second World War artists had this dual opportunity was due to the circumstances under which they worked. Unlike the artists of the First World War whose experiences at the Front were often only a matter of weeks, and whose paintings were often compositionally assisted by official photographs and the recollections of participants, the Second World War artists were commissioned and, to take the army as an example, were attached to specific units for long periods of time. Thus they became very much part of the working environment of their unit and, along with their comrades, uniquely able to observe and experience the theatre of war in which they found themselves. The division between the artist's reaction and that of his associates is therefore difficult to separate, as the experience of war was shared equally, to an unprecedented degree.

7 As a result, while a majority of the works in the collection are useful as a source of technical data in reference to the Second World War, a number also provide important, contemporary insight into the nature of human emotion under the stress of conflict. This is a significant and hitherto unexplored dimension of these works of art.

8 The value of the first-hand visual document as an emotional document as well is made very apparent through a study of the paintings and drawings made by the war artist Aba Bayefsky at the Nazi concentration camp, Bergen-Belsen, in the days after its liberation. A Jewish artist, Bayefsky has continued to revisit the subject matter of the Holocaust to this day. A comparison of his 1945 compositions and his subsequent paintings and works on paper demonstrates that the artist's emotional response in 1945 was very different to that in more recent years. The earlier compositions include sensitively observed portraits of suffering and starving individuals, and a number of moving, but low-key studies of a burial pit. The later emotionally charged works centre on the emblematic strutting figure of a skeleton, quite often wearing Nazi insignia. In a particularly powerful composition, the skeletal figure, portrayed as the "grim reaper," cuts a swathe through a pit of dead bodies. The difference in approach is arguably attributable to the fact that less was known about the extent of Nazi atrocities in the immediate aftermath of V-E Day than became apparent after. Thus, with greater knowledge, the artist's painted response became more vehemently angry. However, the works of 1945 demonstrate very clearly that the evidence of human suffering was the central focus of the artist at the time of his visits to Bergen-Belsen, and that the politicization of the later work is a function of second-hand knowledge gained later, rather than at the time. This is not to decry the importance of the later work, but to suggest that by studying particular works of art, revealing information concerning the emotional tenor of a particular period can be gleaned.7

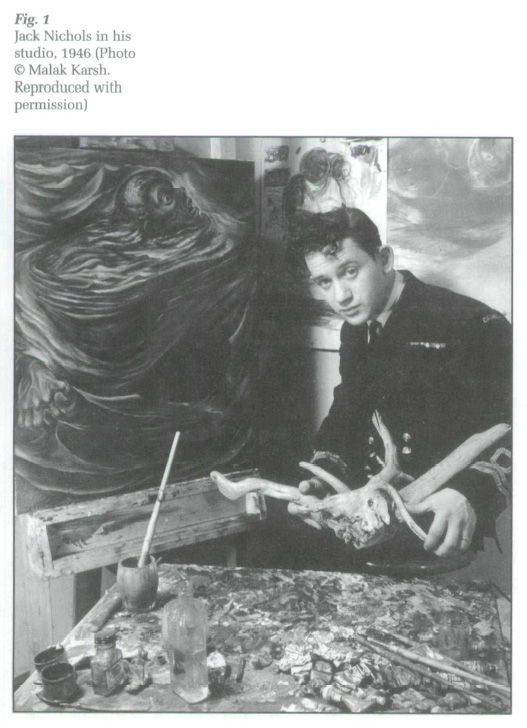

9 Jack Nichols, one of Canada's official naval war artists, is another who looked death in the face and recorded the emotions of the wounded and dying on paper and canvas (Fig. 1). A photograph of the artist in uniform — his paints, brushes, oil, turpentine and palette before him — shows him sitting in front of his most powerful painting, Drowning Sailor.8 In this painting a terrified mariner clutches uselessly at the water as he is pulled down into its depths. His eyes bulge, his mouth is open in a scream, his convulsed face is a portrait of abject terror. In the background, behind the artist, are two sketches. One is obviously a study, presumably now lost, except that it features two heads in the water. The artist himself, in the centre of the photo, holds a piece of driftwood. The dead wood could be considered emblematic of his tragic subject. It is similar to that which he used in the foreground of his painting Normandy Scene, Beach in "Gold Area, " a study of human emotion in the aftermath of battle.9 In a likely unintended parallel, the artist's eyes roll up above the sea of paint and sketches, away from the dead wood and twisted tubes of paint, in an unconscious echo of the composition beside him. None of the seven other naval artists commissioned under the Canadian War Records program chose to depict death or the fear of death so directly. For this reason Nichols's work provides a unique document as to how the average Canadian sailor dealt with it and lived with it.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 110 There were seven other naval artists: Anthony Law, Harold Beament, Leonard Brooks, Michael Forster, Donald Mackay, Rowley Murphy and Tom Wood. None of them painted death by drowning, preferring to concentrate on scenes of action at sea, ship portraits and harbour scenes. Why was this? Did they disagree that death was a factor in the average sailor's wartime career? Were they simply averse to painting the dying and dead? Harold Beament seems to have felt that he was obliged to present a positive view of the Navy, as he was a serving officer as well as an artist. "Beament's main problem," writes Joan Murray, "was in separating the officer from the war artist. He wanted to present the ships as sea-worthy from the Navy's point of view — which caused, [he felt](aesthetic) 'constipation'."10 Donald Mackay agreed. "Like Beament, he found the necessary accuracy of depiction inhibiting."11 Leonard Brooks too is recorded as having seen his role as seeking out the positive in the midst of horror. "Brooks felt the war artist had a special role. Like the doctor or priest, he added the constructive human element in the midst of the horrors of war."12 Tom Wood saw sailors drown, and was present on the Normandy beaches on D-day, but preferred not to remember the tragedies, and thus did not depict them.13 Anthony Law was deeply affected by the 1945 destruction of the motor torpedo boat flotilla he had served with, but his mourning took the form of a more general change in subject matter from scenes of optimism to scenes of adversity, and in a change of palette towards purple and yellow, the colours of Easter and of sacrifice.14 Actual depictions of death, however, are absent.

11 As for artists in the other services, death, when referred to at all, tends to have been symbolized. The army war artist Campbell Tinning was particularly fond of a work he had painted entitled Canadian Graves at the Gothic Line.15 "The olive tree (the symbol of peace) and the grey sky were there and possibly were fortuitous, but their message comes across," he stated.16 When it came to depicting the enemy there was less reluctance to be more graphic. The careful detail of Charles Comfort's Dead German on the Hitler Line is one example.17 On the back Comfort noted: "I am not given to painting lugubrious subjects of this kind, but at least one horror picture is not inept in this situation." Tragic Landscape by Alex Colville is another example of a work where the subject is a dead person.18 Colville was, like Bayefsky, to enter Bergen-Belsen shortly after its hberation where he was brought face to face with the mass pits of the dead. Bodies in a Grave is the finished painting that can be associated with six related sketches.19 While the impact of Belsen has not manifested itself in his later work as directly as it has in Bayefsky's, some of Colville's later paintings still echo his war art, and demonstrate that the exposure to deaths of all kinds, while not necessarily a strong artistic inspiration, remains emotionally haunting. As the author has written: "The hanging arm of the woman in Diving Board of 1993 makes a direct reference to the dead arm of the upper figure in Bodies in a Grave."20

12 Nichols's interest in the bleaker aspects of the human condition was not complicated by the issues that constrained many of his colleagues. The human condition, even in death, was ultimately what interested him and we know this simply by looking at his war work itself. There is no other entry point as the extant correspondence from the war years that has survived, and the few published reviews and pieces of critical writing in existence are not particularly enlightening. Moreover, while Nichols himself is interested in what is said about his art, he is not inclined to explain it in great detail. To understand his contribution to the documentary record of the Second World War, there is no choice but to go to the works themselves.

13 He was born in Montreal on 16 March 1921. Largely self-taught, his mentors were Louis Muhlstock, a Montreal artist, and Frederick Varley of the Group of Seven. In 1943 he joined the Merchant Navy. In the fall of that year he was commissioned and served on ships both on the Great Lakes and in the Caribbean. In 1943 he was commissioned by the National Gallery of Canada to produce some drawings of his Caribbean experiences, which led, in turn, to his being appointed an Official War Artist in the Royal Canadian Naval Reserve (RCNVR) in February 1944. After training on the East Coast, he sailed for England, arriving just in time to participate in the D-day landings on June 6. Before returning to England, he spent some time in the area around Caen. By August 1944 he had returned to sea and was present at the attempted evacuation of Brest, where the Canadian destroyer, HMCS Iroquois, and several British vessels attacked and destroyed the German convoy attempting to make an escape. At some point during this episode he was injured and he subsequently spent time in England before returning to Canada. He was demobilized in October 1946 having produced an official total of twenty-nine works on paper and nine oils on canvas.

14 He applied for, and won, a Guggenheim Fellowship to study in Mexico in 1947. Consistent in his enthusiasms, he noted in his application: "My basic interest and subject matter is people.. .together with their environment."21 His interest in human tragedy had also been remarked upon, and was expressed well in journalist Graham Mclnnes's 1950 book, Canadian Art:

By the time J. Russell Harper had published his second edition of Painting in Canada, in 1977, Nichols had largely retired as a practising artist. However, Harper did draw attention to another aspect of Nichols's war work, other than his humanism, and that was the religious dimension. "Jack Nichols painted groups of sailors and the huddled pathetic refugees being evacuated from the French beaches, and he saw them with a religious aura."23 In Nichols's war art, this is borne out in two drawings in particular (Fig. 2): Ammunition Passer, which makes reference to the head of Christ carrying the cross on the road to Calvary;24 and Head of a Wounded Soldier Crying, which is reminiscent of traditional depictions of Christ's mourning family.25

15 These two important historians of Canadian art both refer to Nichols's war commission as being significant. Certainly this commission remains his most celebrated body of work and constitutes the major legacy of an artist with enormous potential who somehow lost his way, for he did little work of equal force after. While it has undisputed value in terms of its artistic quality, what is of interest here is its value as an important document of wartime emotional experience.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 216 One issue that arises when discussing the evidentiary value of Nichols's war art that is also applicable to war art in general centres on the fact that a painting or a drawing is not a photograph. Rather, the artist shapes what he sees and thus distorts the evidence of his eyes. It is known, for example, that artists such as Alex Colville and Lawren P. Harris composed their canvasses using elements taken from a number of sketches and watercolours.26 While the individual elements may well be based on original observations, the resultant composition is not necessarily a depiction of a single reality.

17 In the case of Nichols's Drowning Sailor, the photograph referred to earlier indicates that there once existed a preliminary drawing for the subject that featured two sailors' heads. Given this fact, one might ask how much literal truth there is in the final composition of a single figure. Perhaps not much, but that kind of truth may not be the most important. What may be more important is the question of whether the depiction of the drowning sailor encapsulates that particular experience of death in a way that is universally, as opposed to specifically, meaningful.

18 A recent acquisition by the Canadian War Museum of a tiny graphite drawing by Nichols of a single drowning head confirms that the artist did work with a single image of a head. The drawing was completed in the aftermath of the action at Brest in 1944, when the artist was on board HMCS Iroquois. It is in no way a completed drawing, and despite the fact that it is of a single head, should not be considered a study for the larger composition. It is rather an attempt to capture on paper the salient details of an act of drowning that the artist had recently observed. The connecting element with the painting of the same subject is the portrayal of the emotion felt by the sailor facing death by drowning.27 The fact that the two heads do not share any particular likeness is irrelevant. The fact that we do not even know the nationality of the victim is also unimportant. The drowning sailor is Everyman, and what the artist appears to have wanted to express was an abstract emotion — anguish in the face of death. His interest was not in portraying a particular person or event.

19 While in the case of Drowning Sailor the act of dying is recorded, Nichols also seems to have been interested in conveying to his viewers the fact that death was a constant fear for any Canadian sailor. In a majority of his RCNVR compositions, his subjects emanate a sense of foreboding. The means he uses to convey this sense of imminent doom are varied. To begin with, in his portraits he chooses to reveal something of the skull, skeleton and flesh beneath the skin's surface. The appearance of naked and unprotected flesh is a powerful visual image. Thus in the drawing Troops Moving Forward the eyes of the sailor in the foreground seem almost absent, presenting the viewer with what could almost be comprehended as the empty eye sockets of a stone sculpture or of a skull.28 In Men Going to Action Stations the muscles, ligaments and bone structure of the sailors are emphasized so that the viewer is aware of the physiology of the subjects, and hence their vulnerability.29 Nichols's preference for a dark and sombre palette and the generally gloomy or tense expressions on the sailors' faces all enhance the prevailing mood of potential tragedy in these works.

20 In his search for some kind of universal truth regarding wartime experiences — death included — Nichols appears to have found that as he moved away from the literal, he came closer to the truth. This can be demonstrated further by a brief study of his approach to depicting life, rather than death, at sea. In an interview he once commented that what impressed him greatly was the way in which the crew of a ship could move about silently, with no light and without getting lost.30 The artist was well aware that the restrictions regarding light and noise were related to safety and survival, so how did he convey this in his work? Essentially what he did, especially in the case of the works on paper, was to remove colour altogether, and in the paintings, to darken the palette so much so that it is hard to identify details in the works. In other words, he sacrificed clarity in the interests of a truthful record of what it was like to be on board a ship in war conditions. Loading Gun During Action at Sea is a good example of a painting completed in this manner.31 The figures emerge only partially from an all-encompassing gloom. The information is obscured for the viewer, yet the imagery is compelling. One senses the tension, the fear and the commitment to the task at hand.

Display large image of Figure 3

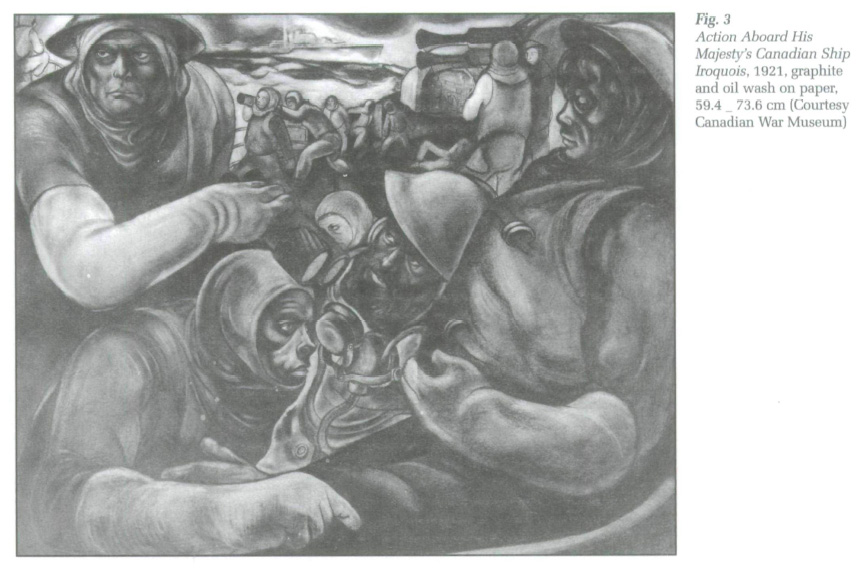

Display large image of Figure 321 Another compositional route that Nichols appears to have followed was seemingly the opposite — to almost provide too much information. In some works he chooses to fill his scenes with a great many figures so that it is at first glance quite difficult to interpret what is actually going on in the scene. This was deliberate. Congestion is an ever-present factor on board naval vessels, and the artist was impressed that within this congestion, and seeming confusion, sailors actually knew precisely what they were doing.32 He took pains to depict this in a number of his RCNVR pictures. Action on Board HMCS Iroquois is a typical example (Fig. 3).33 The figures are plastered one against the other, all concentrating intensely on the multitude of tasks called for at the moment, the seeming confusion in reality nothing of the kind. In fact the confusion, while perhaps artistically problematic, represented the reality of shipboard life in wartime.

22 Judging by their existing compositions, a majority of the other naval artists would likely have treated crowded scenes entirely differently. They would have eliminated figures and the diversity of actions in the interests of the clarity of the composition. This is traditional artistic practice. In the case of action subjects, they would have been likely to provide much more detail in regards to the type of gun used, the crew's clothing, the position of the gun on deck, the kind of ammunition used in the action, and to have provided more light. They were in fact working in the tradition of naval art that had prevailed for most of the preceding two centuries. Yet, in the final analysis it could be argued that it is Nichols's work that, although lacking detail and clarity, provides the more truthful experience of wartime life at sea. It is through artistic means of his own devising that the artist comes close to the essence of the experience, as opposed to simply describing the elements that comprise it.

Display large image of Figure 4

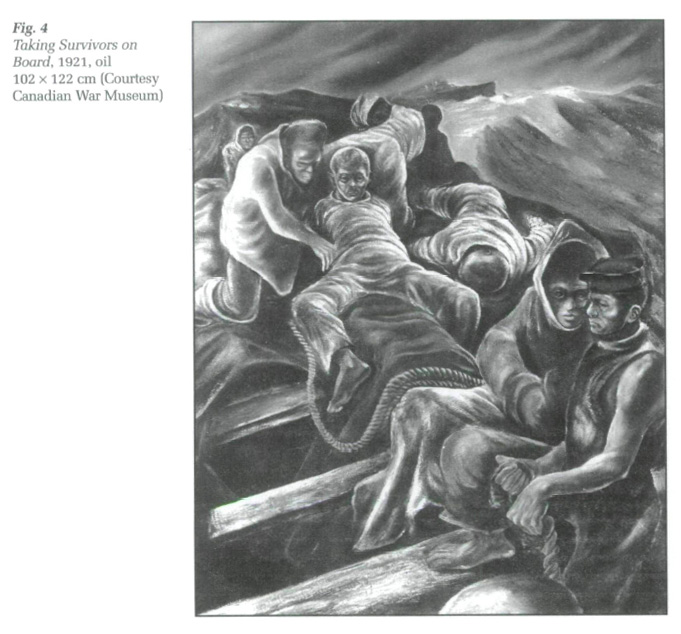

Display large image of Figure 423 In his search for the essential experience of war at sea, Nichols also made use of the viewer's ability to reference other areas of knowledge as a route to understanding the human emotions associated with these experiences. His primary tool was Christian iconography, an aspect of his art that has already been mentioned. In several compositions, it can be argued that the viewers' comprehension of the fear and agony of the protagonists is in part derived from their understanding of these emotions as manifested in the visual subject matter of the Christian faith. In Taking Survivors on Board, previously titled by the artist Rescue at Sea, the scene recalls images of the "descent from the cross" with the wounded Christ figure spread-eagled mid-composition, the mourners, commiserators and helpers around him (Fig. 4).34 As a result, the emotions of sorrow, fear, concern and loss associated with the Christian theme are intensified in the wartime composition through association.

24 Unanswered questions remain to be explored, however, relating specifically to issues surrounding the portrayal of masculinity in his work. By showing men crying in the face of death and dying, some of Nichols's work provides an important alternative to the more traditional portrayals of Canada's Second World War servicemen that conform more closely to familiar masculine military stereotypes. It is apparent that the artist felt that these rather abstract emotions needed to be recorded, and not simply the concrete details of a ship's structure and equipment. It is this element, and the simple power of his imagery, that makes Nichols's war work unusual in comparison to his peers. What makes it particularly interesting is his use of a commonly understood visual vocabulary — often religious at base — to get these abstractions across to the viewer. Thus, that sailors feared death and drowning, and that cold and misery, darkness and claustrophobia were an integral part of shipboard life are awesomely evoked. A range of human emotions not touched upon by more traditional artists is carried in these works of art through solely visual means. As such the works provide an important bank of evidence as to the emotions experienced in the everyday life of Canadian sailors in wartime. In particular, unlike a majority of Canada's Second World War art works, they address the issue of death as well as its surrounding emotions. As such, Nichols's compositions are invaluable tools in expanding our understanding of the naval servicemen's universe of experience.

The author wishes to thank Susan Butlin for the research she did on the artist Jack Nichols in 1995 in preparation for the exhibition Memento Mori, which was immensely helpful in the preparation of this article. The helpful criticism of Dr Cameron Pulsifer, Chief, Historical Research, at the Canadian War Museum is also appreciated.