Coastal Communities / Communautés Côtières

Boat Models, Buoys and Board Games:

Reflecting and Reliving Watermen's Work

Abstract

Generations of watermen from Smith Island, Maryland, have spent their lives harvesting the seasonal round of crabs, oysters, and fish from the Chesapeake Bay. Separated from the mainland by twelve miles of open water, islanders traditionally have created their own variety of verbal and material cultural expressions. This paper explores one aspect of the island's maritime material culture — objects created by watermen, particularly those who have recently retired from full-time work on the bay. Created for various artistic and social purposes, these handmade objects, including boat models, a board game, painted figures, and reconfigured crab pot buoys, reflect their makers' strong bonds with their island home and its main occupation. The following presents these items within the context of the island's history and material culture, seeking to understand their role and significance within the community.

Résumé

Des générations de marins de Smith Island, au Maryland, ont passé leur vie à pêcher crabes, huîtres et poissons dans la baie de Chesapeake, de saison en saison. Coupés de la terre ferme par un bras de mer de douze milles de largeur, les habitants de l'île ont engendré un répertoire d'expressions orales et une culture matérielle qui leur sont propres. L'article qui suit examine un aspect de la culture matérielle maritime de l'île, en l'occurrence les objets façonnés par les marins, surtout ceux qui ont cessé depuis peu de travailler à temps plein dans la baie. Créés dans divers buts artistiques et sociaux, ces objets faits à la main comprennent des modèles réduits, un jeu de société, des figurines peintes et des bouées de cages à crabes sculptées. Tous évoquent les liens étroits de leurs créateurs avec leur patrie, l'île, et avec leur métier. L'article replace ces objets dans la trame historique de l'île et de sa culture matérielle, s'efforçant d'en saisir le rôle et l'importance au sein de la communauté.

1 This paper concerns a variety of artistic objects created by watermen at Smith Island, Maryland. From boat models to a board game, from painted figures to reconfigured crab pot buoys, all of these handmade objects reflect their makers' strong bonds with their island home and its main occupation — the commercial harvest of seafood from the Chesapeake Bay. The following presents these items within the context of the island's maritime material culture, seeking to understand their role and significance. Using an approach familiar to folklorists and anthropologists, the objects are examined from the esoteric, or insider's, perspective, and are discussed in terms of their construction, use, and meaning within the community, rather than according to external criteria, such as the aesthetic sensibilities of outsiders or the objects' desirability in the marketplace. As folklorist Michael Owen Jones has argued, such an ethnographic approach, which considers the "immediate circumstances in which the [objects are] conceptualized, built, sold, responded to, and used" can reveal a great deal about their cultural significance.1

Smith Island and the Water Business

2 Smith Island is a ragged patchwork of land and marsh, lying 19 kilometres off Maryland's lower Eastern Shore, in the middle of Chesapeake Bay. It is the state's only inhabited offshore island. Since English colonists first settled there in the late seventeenth century, this low-lying, windswept landscape has been home to generations of their descendants. For most of their history, islanders lived by farming and fishing. By the late nineteenth century, however, much of the island's acreage, including its most fertile soil, had eroded into the bay. As a result, islanders abandoned agriculture altogether and turned their full attention to the commercial harvest of oysters, crabs, fish, and other seasonal delicacies from the Chesapeake. In 1910, the population of Smith Island hovered around 800; today there are only about 400 people who live in the island's three villages of Ewell, Rhodes Point, and Tylerton.2

3 With the seafood business at the centre of life at Smith Island, it is not surprising that the community boasts some of the bay's most proficient watermen. The majority of island men are independent watermen who own their workboats and sell their catch to an array of seafood buyers. Despite a sea of regulations about where, when, how, and how much they can fish, watermen still perceive themselves as independent operators, free to work as much or as little as they please and to press the limits of the laws governing any fishery. A highly competitive group, they also place great value on the mastery of occupational skills acquired over time.

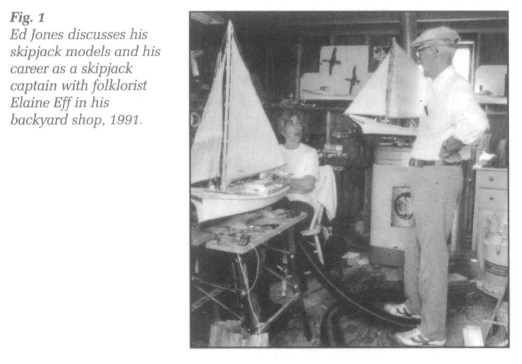

4 Besides being exceptional watermen, Smith Islanders also are known for their distinctive dialect and use of speech. In the 1960s, folklorist George Carey documented the lively verbal traditions among island watermen, who habitually gather in local general stores or in crab shanties to swap complaints, stories, and humour. These verbal forms invariably reflect their personal experiences on the water or the exploits of figures from the community's maritime past. As Carey observed, "With the water consuming almost the entire working force of these small towns, it is not surprising that the general bent of conversation turns on the occupation."3

5 As in virtually all North American fisheries, troubles have been brewing in the Chesapeake Bay seafood industry. Due to a combination of factors including over harvesting, pollution, oyster diseases, and destruction of habitat, it is becoming more difficult for watermen to make a living. Bay-wide, the number of full-time watermen has decreased since the 1980s. Smith Island has been affected by these downward trends as well. As watermen find it harder to support their families, some have quit the business entirely and moved to the mainland to work for wages. Those that remain, however, still comprise, with their families, a unique, single-occupation, maritime community.

Maritime Landscape and Material Culture

6 The cultural landscape of Smith Island is complex and dynamic. A researcher knowledgeable of maritime material culture in other regions of North America would find many familiar — though not identical — forms at Smith Island, where nature and culture collide and cohabit at every compass point. Submerged skiffs sprout marsh grasses; high tides lap at shanty doors; sunburned watermen scoop up soft crabs from the shallows; narrow skiffs shoot through narrow guts.

7 Not surprisingly, workboats dominate the Smith Island landscape. They rim the harbours and are the most important category of material culture in the water business. The fleet, consisting of about three hundred craft, includes traditional boat types of the Chesapeake Bay — vessels developed over time to suit the region's particular environmental conditions and working purposes. The most distinctive of these are crab-scraping boats — beamy, shallow draft, low freeboard craft used for harvesting peelers and soft crabs in the grassy shallows surrounding the island. Other types include deadrise workboats, the generic term for V-bottom craft used for oystering, crab potting, or clamming. Most numerous among working craft are flat-bottom skiffs, which islanders use for netting crabs, hook-and-line fishing, basic transportation, and sport. The fleet comprises a significant maritime resource in terms of number, variety, and age of the workboats in a single community.4

8 In addition to workboats, distinctive vernacular buildings also populate the Smith Island landscape. Plywood crab-shedding shanties built on pilings ramble along the shore; adjacent piers, criss-crossed with PVC pipes, carry bay water to interior shedding floats. A shanty is a crabber's domain, for it is where he docks his boat and deposits his peeler crabs in tanks until they shed their shells, becoming valuable soft crabs. The waterman's shanty, as well as his outhouse (the term for any out-building, usually located in one's backyard), serve as storage for gear and spare parts. They are also where watermen repair equipment, construct crab pots, and, basically, tinker with stuff. Larger equipment is piled outside — before crab season opens in April, mountains of wire crab pots tower beside shanties and fill small backyards. Rusty oyster patent tongs, hand dredges, culling boards, and old engines also occupy the spaces between buildings and boats. With limited land on an island, watermen make every square foot count. In the same spirit, they recycle and re-use parts, and are reluctant to discard anything that may yield spare parts in the future. The material world of Smith Island, especially along the shore, clearly reflects a working landscape, a place devoted to extracting seafood from the Chesapeake. As George Carey noted, "There is little to suggest a profession other than following the water."5

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 In the course of a project to document traditional workboats at Smith Island, I found it impossible to ignore the preponderance of other expressive cultural forms, from yard art to grave markers to foodways, which were connected, in one way or another, to the island's occupation. Images of workboats appeared on house signs and tombstones; families decorated their yards with crab shedding floats, skiffs, oyster tongs, and channel markers; crab cakes, clam fritters, or fried oysters were a fixture at any number of church or community events. When my research (which took place mostly at the local marine railway, along the shore, or on the water) brought me indoors to interview watermen and boatbuilders, I found still other types of maritime material culture. Interior spaces in shanties, outbuildings, and homes contained objects conceived of and made by watermen for artistic, entertainment, commemorative, and social purposes. Like the stories told in local stores, these objects, discussed below, represented and reflected their makers' lifelong occupation and island community.

Models from Memory

10 As in maritime communities elsewhere, Smith Island has its share of model boat builders. The miniature boats built by both retired and active watermen reflect the region's distinctive work-boat types — sailing schooners, bugeyes, skipjacks, and crabbing skiffs, as well as power craft, such as oyster buyboats, scraping boats, and deadrise workboats. The models fall into two basic groups: boats personally known to the builder and made for himself, his family, or other members of the community; and models of regional types, especially sailing workboats of the past, made for outsiders.

11 On one of my first visits to Smith Island in 1990, I met Ben Evans and Ed Jones, two retired watermen in their late seventies, who were building boat models in their tiny backyard outbuildings (Fig. 1). Evans had built a handful of models, including some bay schooners, which were for sale in the local general store. Jones, a retired skipjack captain, was producing a variety of boat models but was concentrating his efforts on building model skipjacks for the developing tourist trade. Both Evans and Jones built their models based on memories of boats they had once seen or worked aboard. Neither used model-building plans, nor did they build the miniature boats to any measured scale or standard of precision. Rather, Evans and Jones built the models according to basic proportions they remembered from their intimate knowledge of and lifelong experiences with full-sized craft. In these respects, their approach was similar to many folk model builders, including those at Harker's Island, North Carolina, discussed by folklorist Charles Zug.6

12 While model makers are surely motivated by a variety of factors,7 both Evans and Jones were motivated by an impulse shared by many retirees: having been active watermen all their lives, neither could stand being idle in retirement. According to Jennings Evans, who was related to both men, neither of the men could have concentrated on model building while they were still working on the water. They wouldn't have had the time or patience. Yet when they retired, neither could keep still. And, unlike most watermen who have, as Jennings said, "clumsy hands or arthritis," Evans and Jones were able to manipulate materials to produce miniature craft.8 Building model boats was a way for both men to utilize their knowledge of local watercraft and to express their continuing identification as members of their occupational group.

13 Elmer "Junior" Evans is another local model builder, who estimates he has built about twenty-five boat models since 1980, when he took up the hobby. Evans is an active waterman who is a generation younger than Ed Jones and Ben Evans. One of the first models he built was to commemorate his first workboat, a round-stern deadrise named for his wife, Mary Ruth. The original Mary Ruth had been built by a local boat builder in 1961, when Evans was just starting out on his own. Years later, he sold his round-stern workboat and bought himself a new fibreglass model. Yet he still harboured affection for the Mary Ruth, and set about recreating her in miniature, plank by plank. More than a decade later, the little round-stern holds a prominent place in Evans's home and is clearly meant as a keepsake and an object of memory, not simply a decoration.9

14 More recently, Evans has built models of local deadrise workboats and scraping boats at the request of their owners. At the same time, he has reached further into his own working history and begun building model skipjacks. (As a young man, he crewed aboard his father's skipjack, Somerset, before striking out on his own.) Evans builds his models largely from memory, without the assistance of scaled drawings. He begins with the basic dimensions of the actual vessel, then makes wooden patterns for guides. Because he believes that "most skipjacks aren't very pretty, they're rough looking, you know, they don't have good lines," he takes certain liberties in making his patterns. Preferring the look of the bowsprit gently following the rise of the sheer line, he has incorporated this look into one of his patterns, unconcerned about changing the accuracy of a particular vessel's lines. In this respect, he approaches elements of design in the same way as traditional builders of full-sized workboats in the region. Such boatbuilders typically develop certain design features to suit their own sense of aesthetics.10 Likewise, Evans crossplanks the hulls of his models in the manner of V-bottom construction favored by local boatbuilders. While Evans will sell his skipjack models to anyone who wants them, on or off the island, he refuses to advertise or market his craft. "I don't even try [to market the models]. If I ever got orders, it would take the fun out of it."11

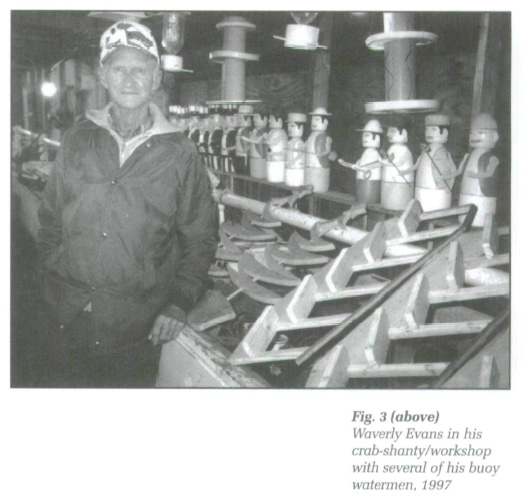

15 In general, the men at Smith Island who build boat models never built full-sized craft. One exception is Haynie Marshall, who, in his seventy-some years has built twenty-four flat-bottomed skiffs. Recently, Marshall has slowed down, retiring from oystering altogether and not planning to build any more skiffs. Instead, he has begun building models of his basic 18-foot (5.5-metre) flat-bottomed skiff, painted the same brownish green he uses on his full-sized skiffs. He also builds models of gunning skiffs formerly used by market gunners on the bay. These models include a scale version of the massive, deadly "punt gun," which is mounted amidships and extends well over the bow stem.

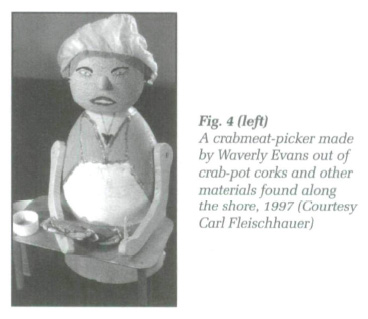

16 How long have watermen been building boat models at Smith Island? Over a seven-year period of visiting the island regularly, I found little physical evidence of boat models that were more than about twenty years old. Of course, this observation is not conclusive; by no means did I inspect the contents of every out-building and home. However, the island's humid environment is hardly conducive to long-term preservation of small wooden objects and it is likely that any older boat models would have deteriorated and been discarded. Yet of the dozens of people I interviewed, no one could remember anyone of an older generation (people born before the turn of the twentieth century) making anything but "crude toys" for children. Such toy boats were nailed together in haste out of wood scraps for children to play with at the shore. But as far as making miniature boats to represent actual vessels known to members of the community, there was no memory of such activity before the early 1970s.

17 Were people too preoccupied with survival, as one islander suggested? Perhaps, but that notion does not account for the substantial periods of time watermen spent "yarning" in the local stores. The expressive verbal traditions noted above occupied a considerable amount of time on a regular basis, filling a social need on an island where options for entertainment were limited. The local store continues to serve this social function, but now some watermen also spend time crafting materials on their own, in addition to swapping stories with each other. Their interest in making miniatures of bay workboats may have much to do with the particular context of the current fishing industry. As the seafood business declines, there is a gradual decline in the number and variety of vernacular working craft at Smith Island and elsewhere around the bay. Perhaps the impulse to historicize these vessels, whose days are surely numbered, is stronger now than in the past.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2Buoys into Men

18 Another type of expressive material culture comes from the hands of Waverly Evans, a lifelong waterman, who was born in Tylerton in 1926. Like many islanders, he patent tonged for oysters in winter and fished crab pots in summer. A few years ago, when the winters got to be too rough and his old round-stern deadrise became too much to maintain, he gave up winter work on the water. He now fishes a modest one hundred crab pots in summer out of a large open skiff. With time on his hands during the long winter, he spends it in and around his crab shanty making things — artistic objects that reflect his life as a waterman.

19 Shortly after what he calls his "semi-retirement," Evans went to work on his crab shanty, painting it in a style unlike any other. Most Smith Island shanties are weathered to a soft grey; some are painted white or red and one in Ewell inexplicably sported a coat of neon green for a few years. Using paint he had on hand to maintain his workboat, Evans painted his shanty white with a wide band of sea-mist green (a favourite shade for workboat trim) at eye level. He proceeded to paint scenes within the band of green — men in skiffs, crabs, fish, channel markers, workboats — motifs from everyday life at Smith Island.

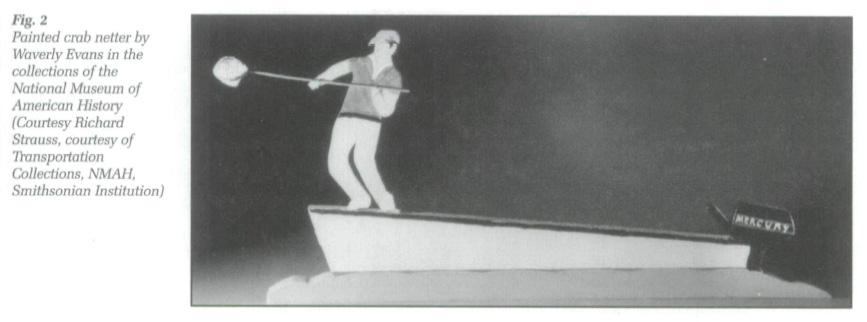

20 Evans's creativity did not end with the shanty. In 1996 he began making objects that appear to have no precedence on the island, or elsewhere in the region, for that matter. He began making flat, painted figures, measuring roughly twelve to eighteen inches in length, out of scraps of wood. The figures (Evans does not have a name for these objects, but tends to refer to them as his "crab netters") are profile views, almost caricatures, of watermen aboard skiffs (Fig. 2).

21 Evans has made dozens of these figures in a variety of postures and pursuits, capturing the body language of watermen netting crabs, landing a fish, or planing a skiff with a dog in the bow. There is one constant in all the figures: each skiff is powered by Evans's preferred motor — a Mercury outboard. According to Evans, his first effort — a waterman standing on the bow of a skiff with a crab net held aloft — shows a netter who has scooped up a "doubler," a pair of mating crabs, which islanders also refer to as "a husband and wife." With a flick of the wrist, the netter flips the pair into the air to separate them. If the manoeuvre were brought to its conclusion, the netter would twist the long handle of the net to catch the female, the more valuable of the pair because she will soon be a soft crab. The "jimmie" (the local term for a male crab) would be left to find himself another "wife." These deft motions — second nature to islanders — are what Waverly Evans has captured in his simple wooden figures.

22 Evans begins by drawing the figure on a piece of 1" x 6 ' (2.5 cm x 15 cm) pine, then cuts it out with a skill saw. He paints each piece, using the same colors he used for his shanty — sea mist green for water, white for the boat, a black line to mark the sheer, and red to resemble anti-fouling bottom paint on the skiff. The finished pieces are meant to stand on their own or be hung on a wall.

23 In the same manner that watermen recycle equipment, Evans combs the recesses of his shanty and the shore for materials to use in constructing his figures. He makes the long handle of the net out of heavy gauge wire. For the netting, his wife suggested he use pieces of a synthetic "cleansing puff' they had received as a free trial offer from a beauty soap manufacturer. The mesh of the cleansing puff is nearly the correct scale and has just the right look when attached to the wire rim. The final touch is a tiny crab shell, to scale, which is glued inside the net.

24 Evans has no ready explanation for how he came to populate his crab shanty with wooden watermen. When pressed, he says, simply, the idea "just popped up" and "I've always enjoyed making things." The inspiration for the original design, which he named "01' Dub" (for "doubler" crab), came from memories of late-summer crabbing. He recalled, "when I was a kid we used to net around a lot. We don't do it much anymore."12 Making the figures started out as a hobby; it was something to do with the leisure time he suddenly had after retiring from oystering. Evans did not intend to sell the figures, but his neighbors and the occasional tourist saw them, liked them, and were willing to pay a modest price. Those he has given away or sold on the island decorate both public and private spaces, such as the exterior of an outbuilding or the bedroom of a child.

25 Evans expanded his creative endeavours when he began making "cork people," or images of watermen out of used Styrofoam crab pot floats (Fig. 3). Using what he calls "bullet corks" (because of their shape) for the body, he places a smaller round float on top of it for the head. Evans makes baseball caps (the preferred head gear for watermen) out of the end of yet another cork and arms out of thin pieces of wood. The arms are nailed to the bullet cork and support tiny crab nets or fishing rods. Evans gives each "buoy man" a colorful outfit and facial expression. While they seem to resemble watermen in the community, Evans does not admit to fashioning them after individuals. Like the corks that mark the location of submerged crab pots, those transformed by Evans are complete with sticks protruding from their bases. The sticks, which the crabber grabs when throwing the pot line around a mechanical hauler, provide the means for displaying Evans's creations — shoved in the ground, the buoy men become yard decorations.

26 After making a few dozen cork watermen, Evans tried his hand at capturing the image of the island's female crab pickers (Fig. 4). He gave his first female figure, also made from recycled crab-pot buoys, to the women who had organized the Smith Island Crab Meat Coop in Tylerton.13 This figure, complete with table, knife, crab shell, crabmeat container, and refuse can, sits atop the desk in the co-op office. With its requisite apron and hairnet (mandatory attire, according to Maryland Health Department regulations), the figure commemorates recent efforts by community women to "go legal" with their crabmeat picking operations. In a moment of whimsy, Evans added some fancy finishing touches to the crab pickers: glitter outlines the apron and the pickers wear jewellery made of tiny shark's teeth. Like the used buoys and crab carapaces he uses to make the cork caricatures, Evans finds fossil shark teeth in the marsh and along shore.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4The Crab-Pot Game

27 Each October, at the beginning of oyster season, Smith Islanders engage in a ritual that harkens back to the days of oystering under sail. Then, captains and crews would depart for ports to the north ( "up the bay") to harvest oysters aboard sailing dredge boats. For the past twenty-odd years, many of the community's watermen take their deadrise power boats to distant towns to work during the week, returning home on weekends.14 The men stay aboard their boats, forming a floating dockside community in various ports around the bay. After a day's work, they typically have a meal at local restaurants and read, play cards, or talk with each other in the snug workboat cabins before retiring. It was during one such winter of oystering more than twenty years ago that Ewell waterman Jennings Evans started thinking about the coming crabbing season and came up with an idea. "I was a-thinking one time, I said, 'Gee, wouldn't it be nice to simulate crabbing without having to go out and face the high seas and the hot weather and all?' "15

28 From that idle thought Evans developed a board game that re-creates the experience of crabbing for a living (Fig. 5). Similar to Monopoly, the game involves four players, each manning a small workboat as it moves around the game board. One trip around equals a day of crabbing; a game usually consists of six times around the board, or a week's worth of work during crab season (islanders, staunch Methodists, observe Sunday as a day of rest). Evans is another example of the waterman-recycler. To make the game, he papered over an old game board and drew the cartoon illustrations for each space himself. He fashioned the workboats out of Winston cigarette hard-packs (shirt pins serve as radio antennae), and made the barrels and baskets out of cardboard.

29 At the beginning of each game, one player turns a spinner on a card to set the basic framework for the game — the market price for crabs, and the costs for bait and fuel. As in real life, these factors are beyond the control of water-men, yet they have tremendous significance. Players roll dice to move their boats around the game board. The lucky crabber lands on spaces that allow him to bring aboard one, two, three, or four baskets of crabs. However, as in the real world, there are all sorts of unanticipated problems.

30 For example, a player landing on a trouble spot draws a card that reads: "Lost in fog this morning. You need new compass. Buy compass in port. $100 cash." Another may say: "Coast Guard Inspection. You need new life jackets, fire extinguishers, a bell, a horn, and a wishel [mimicking the accent of one of the inspectors.]. Get new equipment in port. Cost $150." Another card reads: "Crab pot on your wheel [pot line on your propeller]. Go directly to railway. Bill for hauling $30. First put out your catch." Another: "Sea nettle in your eye. OUCH! You're KILLED. Quit fishing, and go home for rest of the day. Put out your catch in port."

31 In discussing the background of this particular problem, Evans explained, "Well, when you're out on a boat and you get stung in the eye, sometimes the sting is so heavy and the pain's so dense that your eyes begin, you know, water begins pouring from 'em and you have to go in. You can't see your pots or anything. Now, not in all cases. Sometimes you get a little bit in the corner of your eye. You can endure that. But when it gets right in the eye, that means you're done for the day...it's very painful. And although this is a joke, it's very true."

32 Other spaces marked "Long arm of the law," involve getting cited by the state marine police for familiar infractions:

Since no one can make money in jail, Evans created the "Sharky Fin Loan Company," whose motto is "If you're in a financial bind, then come on in, the water's fine." Players may borrow money for bail, on the understanding that they have to pay it back the next time around the board. When players do not catch enough crabs to meet expenses, they also have to borrow money from the loan company.

33 All is not toil and trouble in the crab pot game, however. Landing on certain spaces entitles the player to draw from the "Helper Card" pile or the stack marked "Big Deal Bonus Card." Here is where wonderful, unexpected things can happen. For example:

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 534 Evans explained how the game reflects the experience of crabbing: "One day might be a disaster for you, but the next day, you know, might be good for you. It's the way crabbing is. I know it's hard to pay these penalties on the board, but when you're crabbing, you have to pay those penalties every day. That's the hazards that await everybody. Hopefully, they don't happen, you know, every day, but the odds are you're going to experience one of these things that's in these cards at least once every two or three weeks, something, you know, needs repairing or something is going to break down or you'll find your engine broke down at times."

35 He continued: "Of course, in real life, you depend on, you know, your neighbour coming by or your fellow crabber. Most of the time they've got a keen sense when somebody's in trouble out on the water here. You've all got radios now, and you just relay the message that you've broken down and the closest one to you a lot of times will come pick you up...They won't let you lay there, you know, if it starts to breeze up or anything. So there's some of the hazards that you face in real life, and I've tried to simulate them on this game, you see. I think it would help children, you know, to realize what a waterman has to go through without actually having to go through all the rough weather and the freezing weather and the hot weather, and it would give them an idea of just what the water business is all about, without the pain."

36 While educating children may have been in the back of his mind as he developed the game, Evans and his cohorts have been the major players. Recalling the players' reactions to the game after they played it for the first time, he said: "At the end of the game, we all decided it was similar to the real thing. One of 'em said, 'It proves one thing. If you don't get the market, you're not gonna make any money.' That was what I wanted to hear, you know, for the first game. It was similar to the real life thing, although it was just a game."

37 Over the years, Evans played the crab pot game with other watermen aboard his boat when working away from home, mostly near the end of oystering season, in late February and March, "when the skim was gone" and they were "just dipping."16 At that time of the season the tongers would be anticipating the crabbing season ahead. Now that he's retired, Evans plays the game occasionally with friends who stop by his outhouse. For them, the game is pure entertainment, which doesn't mean they don't grumble and complain about how hard it is to make a living. But at this point in their lives, it's only a game.

Meanings in Process and Products

38 The folk art objects described above have a great deal in common. Each was conceived of and created by Smith Island watermen using knowledge, skills, and, for the most part, materials at hand. None of these craftsmen consulted ship plans or how-to books before beginning, and in only rudimentary ways did they seek the assistance of others. Unlike the majority of traditional artists and craftspeople who serve an apprenticeship at the elbow of an elder, none of these men traced their interest or skill to the influence of any particular individual. Instead, their instruction came, as did inspiration, from a lifetime spent in a small, closely-knit community of watermen intensely devoted to the harvest of seafood resources from the Chesapeake Bay. The particular skills involved in making the objects had little to do with perfecting certain artistic techniques, but had everything to do with such esoteric abilities as instinctively knowing the lines of bay boats, or the silhouette made by a crab netter balanced on the bow of a skiff, or the complex set of circumstances a crabber encounters when trying to make ends meet.

39 Opportunity also played an important role in the creation of these objects. For Jennings Evans, it was the long winters away from home that provided the extended time needed for developing, constructing, and, later, for playing, the crab pot game. For most of the others, it was a matter of having increased idle time after slowing down or retiring from the water business. The relationship between retirement and the desire to engage in creative activity has been noted by, among others, Simon Bronner, in his study of traditional chain carvers, and Charles Zug, in his work about model boat builders in North Carolina.17 From the Chesapeake region, George Carey noted that one of the best raconteurs of Maryland's Lower Eastern Shore, Alex Kellam, began painting at the end of his life. While Kellam was widely known for his verbal wit and remarkable repertory of stories, in retirement he turned to a more solitary creative endeavour — painting pictures of the skipjacks he had worked aboard in his youth.18

40 While retirement provides opportunity in the form of free time, it can also present something of a crisis, for it "entails a shift in status with respect to society."19 Within the Smith Island community, the attitude of "once a waterman, always a waterman" prevails. Retired watermen are widely respected and continue to be consulted about the ways of oysters and crabs, boats and gear. Still, some watermen find it troubling to stay ashore after having spent so many years aboard a boat. The artistic objects, informed as they are by their makers' intimate knowledge of occupationally-related details, provide a means by which a retired waterman can maintain a connection to the occupation and its current practitioners.

41 Similarly, because the retired watermen craft the objects in the same physical spaces they used during their working lives, they are still a physical presence among the community's active watermen. Smith Islanders have ordered their limited space according to function, an arrangement that reflects work practices as well as established and conventional notions of gender roles. In every case, the objects were made in male-dominated spaces — crab shanties, outhouses, aboard a workboat. As Charles Zug observed with model makers in North Carolina, the process of making these objects continues "patterns of male independence so important during working life."20 Retired watermen generally don't sit around the house all day; if they're able, they go down to the water to do minor jobs in their shanties, socialize with each other, and continue the familiar occupational banter. Messing around in these occupationally significant spaces communicates their continued identification with the water business, despite their reduced role. Continuing to be productive in these spaces by making objects which express the knowledge, skills, and values associated with their lifelong occupation reinforces their status as engaged members of their communities.21

42 Of the three groups of objects discussed, the boat models are the most widely known examples of maritime folk art. The practice of sailors and fishermen crafting miniature reproductions of vessels is so widespread, it would have been unusual had I found no model builders at Smith Island. Susan Stewart has written extensively on the phenomenon of miniatures, observing that objects (like boat models), are often imbued with nostalgia and that the desire to make such objects in miniature (as well as their wide appeal) springs from an urge to capture a vanished era.22 In many respects, this applies to model boats made by Smith Island watermen. The model of a particular vessel, like "Junior" Evans's round-stern Mary Ruth, was created out of a desire to make something tangible to commemorate a period in the past that had special meaning. Likewise, viewing the completed miniature — a small version of his first workboat, one named for his wife — provokes a nostalgic response that may involve a longing for the time when he was embarking on what has become a satisfying working life.

43 Islanders' skipjack models, even those built for outsiders, also carry this evocative power. Skipjacks — the sloop-rigged, sail-powered vessels that comprise the last commercial fishing fleet in North America — have become virtual icons of Chesapeake Bay history. Smith Island's present landscape carries few clues about the importance of these vessels, called "oyster drudgers," to the community's past. But, thanks to Jennings Evans and others, the relationship between islanders and dredge boats is revealed. Evans has compiled a list of all the skipjacks known to have been captained, at one time or another, by Smith Islanders. Seventy-nine vessels are on the list (out of a documented 536 skipjacks), which provides only a hint of the number of islanders who worked aboard dredge boats in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.23 Scores of islanders also worked as crew, hauling dredges, culling oysters, running the push boat, and tending sails. The community's last skipjack, the venerable Ruby G. Ford, was sold off the island in 1972. In the years immediately following, some of the island's young men continued to crew on vessels owned by captains elsewhere in the bay. With the precipitous decline in the bay's oyster populations since the early 1980s, however, young men no longer work aboard the handful of skipjacks that remain in the Maryland fleet.

44 For the older generation of Smith Island watermen, including Ben Evans and Ed Jones, who passed away in 1992 and 1995, respectively, the waning and ultimate demise of the skipjack fleet — first at the island and later throughout the state — is an event of profound significance. They were the last generation of island captains, the last in a long line of Smith Island Evanses, Tylers, Joneses, and Bradshaws to steer a sailing dredger over the bay's oyster beds. Ed Jones, who captained both the Howard and Lola, was doing more than building models of skipjacks, he was giving form to a time and place, the demise of which he had witnessed himself. Researchers for the Grand Generation exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution noted this relationship between certain builders of model sneakboxes and garveys in New Jersey. These men represented "a cohort that [saw] itself as the last generation to freely hunt and trap the disappearing coastal marshes, and as such [they saw themselves as] co-witnesses and curators of a vanishing way of life and the places in which it was staged."24 Even "Junior" Evans, who never captained a skipjack but who crewed aboard the Somerset for fifteen years, perceives himself as part of this fading era. "It's a part of the past," he said, "it's authentic and unique."25

45 There was a social dimension to the model skipjacks built by men like Ed Jones, as well. The models provided him an opportunity to engage in conversation with neighbours, as well as visitors to the community, on a subject a waterman never tires of— the water business. In a sense, the models drew people in and served as props for Evans to share his knowledge with outsiders, an activity that put him in the role of waterman/expert. Because of the public's fascination with skipjacks, Jones was rarely without an audience during the summer tourist season. As noted by others, the "miniatures are not only lures for memories, they are lures for drawing the world in."26 In a similar vein, Charles Zug found that models of regional boat types in North Carolina became "catalysts for a history of the region" as natives used them to educate outsiders about the region's maritime past.27

46 In contrast to the widespread practice among sailors and fishermen to craft models of vessels from their own experience, Waverly Evans's creations are without discernable precedence on the island, or elsewhere in the region. Evans's figures and crabpot cork creations are more innovative than traditional and represent a more personal response to circumstances — his own semi-retirement, his desire to continue to keep busy by making things, and his highly developed skill for finding, adapting, and re-using materials. Like the watermen who scrounge rusty engine blocks to use as anchors, or who use old beer kegs for fuel tanks aboard their scraping boats, Waverly Evans searches the shore for used crab pot corks brought in on the tide. Many Smith Islanders are "proggers," people who roam the edges of the marsh, looking for interesting things of nature and culture to collect.28 Evans, the progger, is also something of a bricoleur, a craftsman who can see the potential in debris, who can envision a creative mix of shark's teeth, crab shells, bottle tops, and scraps of wire.29 Viewed another way, Evans is merely continuing a long-established pattern of a waterman's work — gathering whatever can be wrested from the waters of the Chesapeake, whether it be crabs, oysters, or interesting flotsam.

47 Personality also plays a role in expressive culture and, indeed, Waverly Evans's impish personal style is reflected in the things he makes. When asked about the inspiration for his cork caricatures, Evans could only reply, "I guess I still got some kid in me!"30 While the process of crafting the cork people provides enjoyment for Evans, his finished products have provoked amusement among his neigh-bours, who are used to poking fun at themselves.31 The shape of the "bullet corks" suggests all too well the physique of many island men. When Evans delivered his cork crab-picker to the Tylerton crab-meat co-op, Janice Marshall reported that she "got to laughing so hard," because he had captured the "look of us ladies, sitting there with our aprons and hairnets, pickin' away."32

48 An outgoing personality, a talent with words, and Jennings Evans's experience on the water underlie the creation of the crab pot game, which combines entertainment and narrative. Watermen who play it can only laugh at the true-to-life, bad-luck scenarios that befall the beleaguered waterman with the roll of dice. In a sense, the game is a physical manifestation of the island's narrative tradition. The circumstances spring from the experiences of Evans and other members of the community and are the stuff of which the yarning tradition is made: troubles with the law; equipment breakdowns; a day's work that barely covers expenses; unexpected good fortune. Like the narrative tradition, where stories both entertain and reinforce occupational values, the game conveys certain messages relevant to commercial fishing: watch out for the marine police, keepyour boat in good repair, and be prepared to laugh and take things in stride because there are too many factors in this business beyond your control. The particular circumstances selected by Evans index some of the more significant aspects of watermen's work. These are the things that resonate among watermen, that need no explanation in the local context. Evans, however, mused about a particular group of outsiders playing the game. "I'd like the IRS [Internal Revenue Service] to play this game," he said. "Maybe then they'd know what we're up against!"

49 In the case of Waverly Evans's "OF Dub" figure, there is entertainment value, to be sure, and to outsiders, the figures represent nothing more than a cartoon or caricature of watermen. However, when the insider's view is considered, another level of meaning is revealed. Like the skipjack models, which represent a vanishing time and place, the lone crab netter represents a set of skills and depth of experience that older Smith Islanders possess in abundance. To what extent those skills will continue to flourish is open to debate, as the population of the island continues to decrease.

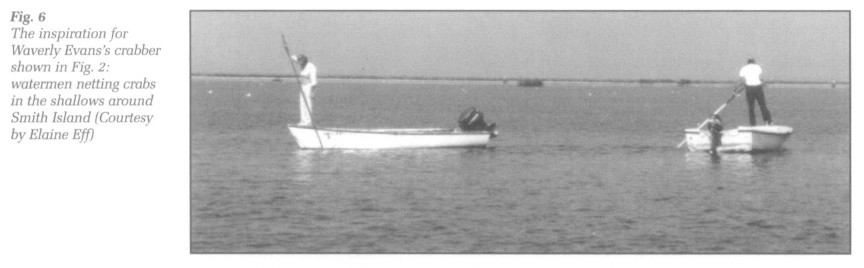

50 Evans's neighbour and cohort, Julian "Juke" Bradshaw, remarked: "Well, it's a lost art, dip netting is. Now, there's a time, from August until the end of the season, there's a time when you can do good dip netting...It's fun, really it is. It's hard work, too, but it's a lost art. I don't know if one of these days there won't be many of us left that will even know how to net...The main thing is to know what you're doing, because a lot of times crabs will be buried [but] you can find them. There's a way to catch them if you know how. A lot of people would shove right over them. But most the time in that part of the season, they're right out open. They're not hard to see, and it really is fun sometimes to catch them."33 Writer Tom Horton, who lived in Tylerton for several years, reported that islanders believed netting was "the prettiest way they know to catch a crab"34 For older residents especially, "Ol' Dub" evokes a place, season, artistry, and a community of netters that others can only try to imagine (Fig. 6). Evans's measure of success is the reaction he gets from members of the community. The display of "Ol' Dub" in a child's room, like the prominent placement of the cork crab-pickers on the co-op desk, indicates he got it right with the people who matter most.

51 There are multiple layers of meaning surrounding these few examples of expressive material culture from a single maritime community. Made for purposes of commemoration, entertainment, artistic expression, or for maintaining social connections, they all reflect their makers' strong occupational and community identity. Some of the objects provoke a nostalgic response, evoking a set of associations about a vanishing past. They also serve a social function, drawing people in for further interaction and, possibly, education. The forms vary in terms of traditionality and innovation, with some, like the boat models, being highly derivative, while others, like the buoy water-men, express the particular talents, personality, and creativity of an individual. Most of these forms are ephemeral; they may or may not last for the benefit of future generations of Smith Islanders. Yet, for most of the makers, the process of creating the objects was more important than was the final product. The range of objects also reflects life in the community at a particular moment in time. Smith Island is, if anything, a place in transition, where the population continues to decrease as the fisheries continue to decline. Other artistic forms are certain to emerge as more islanders begin reflecting on the history and traditions of their maritime community.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6I wish to thank David A. Taylor, Melissa McLoud, Leslie Prosterman, and Elaine Eff, who provided insightful commentary on earlier versions of this paper.