Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

The Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto

1 Everybody can relate to shoes. We all wear them, doff them and scuff them and we sometimes prize them. We also know that shoes reveal a lot about us: things like our age, character, cultural background, and colour of collar. So the opportunity to see shoes from a collection that has been gathered from all points of the globe and spans 5 000 years of shoe making is an intriguing one. Such an opportunity is offered by the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto.

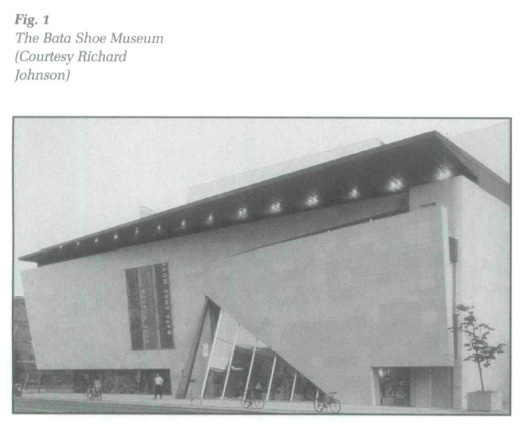

2 The Bata Shoe Museum opened in May 1995, as the showcase for the most extensive collection of shoes anywhere. There are 10 000 shoes in its collection, all of which have been reviewed and approved for acquisition by Sonja Bata, wife of shoe mogul Thomas J. Bata. The museum sits on a corner lot at St George and Bloor Streets in Toronto, on the periphery of the University of Toronto campus and two city blocks away from Bloor Street's upscale shopping district. This is an apt location for a place that addresses shoes as both cultural objects and fashion items. Conveniently for the museum-goer the location is also just one subway stop away from two other Toronto attractions: the Royal Ontario Museum and the George R. Gardiner Museum of Ceramic Arts.

3 The Bata shoe collection entered its nascent stage when Sonja Wettstein married into the Bata family in 1946. The Bata family had been prominent shoe manufacturers in Czechoslovakia for eleven generations until its Czechoslovakian interests were expropriated by Communists at the end of the Second World War. To survive in business, the Batas hung onto their manufactories in western Europe, established plants in developing countries, and in 1946 Thomas and Sonja moved to Canada to develop the outpost Thomas had established here in 1939. Sonja made the shoe business her business and developed a specialist's eye for shoes. Mrs Bata travelled extensively with her husband, visiting the many Bata manufactories and markets in far-flung places from London to Singapore, and places in between including Pakistan, India, Kenya, Malaysia and Uganda. Through her travels her specialist's eye turned to that of a collector, with particular focus in footwear that "was being displaced by modern global production methods" (quoted from Taming of the Shoe exhibit in the Museum).

4 As is often the case with collections of objects bigger than stamps, the collection soon outgrew home storage. In 1979 Sonja Bata established a foundation with non-profit charitable status to manage the collection, and set about finding quarters to house, care for, research, interpret and exhibit the shoes and shoe-related objects. Locations next to the Ontario Science Centre and within the Harbourfront area were considered but rejected. In 1992 a hint of things to come appeared when a formal but temporary exhibit space for the collection opened in The Colonnade, a stylish midtown Toronto retail complex. Finally the location at St George and Bloor was fixed and the permanent home for the collection was subsequently created for the opening in 1995.

5 The permanent home was designed by Raymond Moriyama of Moriyama and Teshima Architects as a gleaming, limestone-clad landmark. Filling a former gas station lot in a neighbourhood of Neo-Gothic and rusticated Romanesque old stone structures, the Bata Shoe Museum rises as a sleek, post-modern cat among the pigeons. The museum's surfaces are smooth, its angles canted, its lines taut. This is a building that telegraphs importance, style and wit. References to its content are playful but subtle. Exterior tan limestone walls remind one of smooth boot leather and the windows look as though someone took a sharp knife to that leather, cut slashes, and pried pieces of it open. Sidewalk window displays designed by the Montreal firm L'Atelier du Presse-citron are fanciful, colourful, multilingual and fun, beckoning the visitor to step through glass doors and into a welcoming central hall. With a three-story-high window as a dramatic backdrop to this hall and its open stairway, Moriyama has created a light-filled, airy space. This serves as a pleasing counterpoint to the closed and darkened galleries necessary to display light-, temperature-, and humidity-sensitive artifacts to museum standards.

6 The theme of sophistication, style and playful wit established on the building exterior is continued on the interior, with various shoe-related details. These are often subtle, and it becomes a game to pick them out. The central hall window, designed by Lutz Haufschild, features coloured glass pieces in shoe-like shapes. Directional signs are made with leather, conference chairs are made of molded plastic that resemble curved pieces of leather, and stair risers are cut with peek-a-boo holes that allow quick glimpses of shoes worn by the museum-going, stair-climbing public. Door handles and decorative stairway fasteners designed by Dora de Pedry-Hunt affirm the authority and importance of the museum with depictions of shoes from the collection cast in heavy bronze medallions.

7 The stairways span five stories in total, two below ground. Building layout is clear, easy to follow, and galleries well identified. Visitor amenities are there: two special events lecture spaces, clean ample washrooms and cloakroom. The gift shop is located on the ground floor as an offshoot of the central hall, so a gift shop stop can be first or last on your visit. Universal accessibility is part of the plan. A passenger elevator provides all-floor access to those who prefer not to use the stairs. Almost all display case contents are visible from small person, tall person and wheelchair height. Circulation space is generous. Never, despite the low light levels required for artifact preservation, does one feel closed in. Information can be accessed through audio and visual media and primary-level exhibit text appears in large, bold type.

Display large image of Figure 2

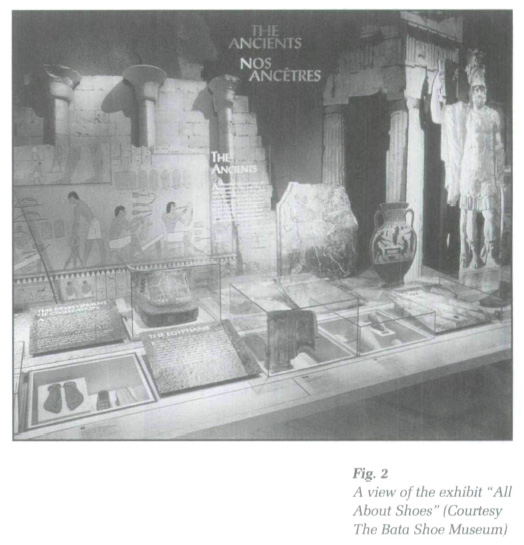

Display large image of Figure 28 Upon paying an entrance fee visitors are directed below ground to see the long-term exhibit All About Shoes: Footwear Through the Ages. As its name suggests, this is the linchpin exhibit, a survey on the subject of shoes. It informs the visitor of the importance of shoes as cultural signifiers, thereby underscoring the importance of the museum itself. Once through AU About Shoes visitors find themselves back in the circulation core facing stairs to the second and third floors, where a selection of ongoing and temporary exhibits are located. On the second and third floors are temporary exhibits including, at the time of writing, The Spirit of Siberia (replaced in winter 1998 by Footsteps on the Sacred Earth, an exhibit of native North American footwear of the southwestern United States), Taming of the Shoe (replaced in September 1998 by Little Feats: A Celebration of Children's Footwear, an exhibit of children's shoes from all over the world), and Dance! (replaced in February 1999 by an exhibit of Japanese footwear with the working title Japanese Footgear: Walking the Path of Innovation). On the way to Dance! visitors pass a window onto the conservation workshop and curatorial and administrative offices, a reminder that the exhibits are supported by other museum functions.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

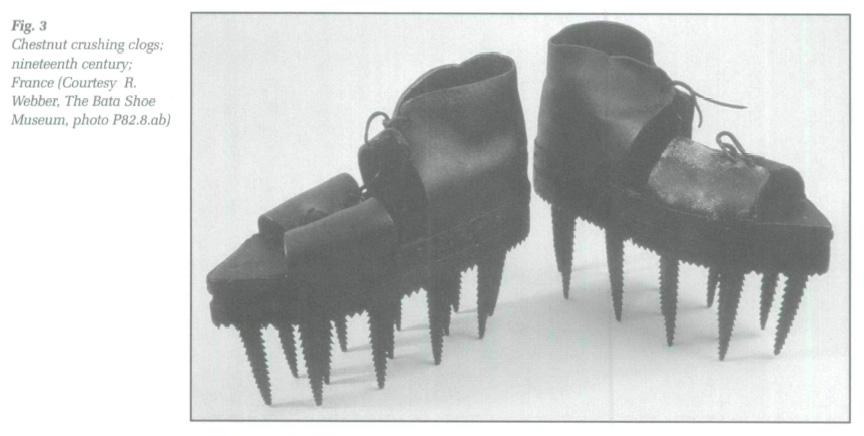

Display large image of Figure 49 All About Shoes gives a general introduction to the subject of shoes and leads well to the more specialized exhibits on the second and third floors. All About Shoes was curated by Jonathan Walford and designed by Design + Communication Inc. Its introduction begins at the beginning with a reproduction of the earliest known human footprints, which were preserved in hardened volcanic ash and discovered in 1976 in Tanzania by Mary Leakey. The original footprints are 3 700 000 years old. Linked to this glimpse of pre-history is the statement that "through our feet, we have come in closest contact with our history."

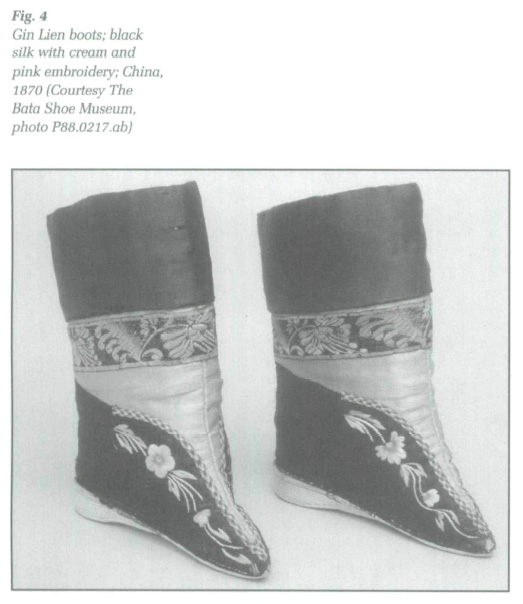

10 With this statement one is introduced to the degree of importance assigned to the shoe by the Bata Shoe Museum. The following five exhibit components make up the core of the exhibit and address shoes as significant in cultural anthropological terms. These five components demonstrate that shoes began as strictly functional items but soon became expressive of cultural values and systems. Such values and systems are identified as social status, rites of passage, religion, occupation, and fashion. The footwear shown to illustrate these themes embody for the average visitor the distant and exotic, the familiar and pedestrian, peaks of accomplishment in human history, and oddities in cultural practice. There are some truly remarkable items on display here, prompting superlatives. There are shoes, sandals and boots that must be the biggest ever made, the smallest, the most ingenious, and even the most blatantly hegemonic. While following the exhibit's theme of footwear as cultural signifiers one cannot help but stop and contemplate the superlative nature of some of these objects.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 511 In a display component that presents footwear that signify the wearer's occupation is an enormous pair of French coachman's boots from the early nineteenth century. Their immense size combined with colour (black), material (thick leather), and form (thick-set) make them an intimidating and wondrous sight. Label information and a touch-screen presentation dissolve some of the mystery of these dark boots. They were used as coach equipment rather than personal apparel, and were designed to stay with the coach to accommodate each coachman's already booted foot, hence their size. Their hardy, almost brutal form was prompted by their prime function: to protect the coachman's legs and feet from the crushing effects of a horse's fall.

12 The smallest shoes on display are three-inch-long Chinese shoes made for women who had their feet bound in childhood to inhibit normal growth. They are horrific to the sensibilities of a 1990s visitor for their association with the now-defunct practice of foot binding, but the same visitor can divine and appreciate the elevated status accorded the wearer through the beauty of the fine materials and refined craftsmanship used.

13 There is a tie for the most ingenious footwear. It is between Dutch clogs and American army boots. The clogs have soles carved to leave an imprint of a foot going in the opposite direction from the wearer's path. They were used by Dutch smugglers circa 1940 during a time of limited trade and rationed goods. Perhaps the designer of the 1960s American army boots knew about such Dutch clogs. The army boots have soles fashioned to leave footprints in the shape of a Vietcong sandal. The most blatantly hegemonic and overtly expressive items are a pair of sandals worn sometime around 1930 by an Asante king for state occasions in Ghana. Their very large black soles are fashioned in the silhouette of a man, and the wide top straps are decorated with chunky gilded wooden carvings of a king on his throne and his two wives. These are sandals with attitude.

14 A nod to technology follows the five components of shoes as cultural signifiers. Shoe-making tools and a mini diorama of a shoemaker's workshop are displayed along with text, pictures and two videos. Each video describes the step-by-step process for making shoes. One explains pre-industrial shoe making in a cobbler's workshop, the other outlines post-industrial shoe making on an assembly line. The point of this display component is that the manner of making shoes changed little for 7 000 years until mechanization transformed the workshop into a production line. The videos simply describe process, leaving the visitor to speculate about this significant change in production methods. One wonders if the change affected the way we use and think about shoes, and one wonders further if the evidence of this change is obvious in the Bata shoe collection.

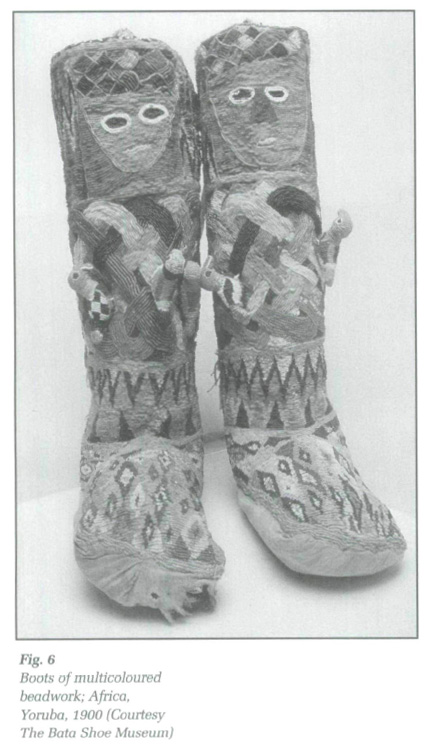

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 615 From these ruminations on technological change a visitor's attention is diverted by the strains of music beckoning one up a zigzag staircase to a mini theatre labelled Star Turns. Along the way are cube cases showing shoes or shoe-related artifacts in a novel form of open storage. Star Turns turns out to be a sound, light, and artifact show. To see the show visitors can settle onto a bench in a mini theatre that will accommodate approximately fifteen people seated and many more standing. Star Turns displays the shoes of fifteen famous people and one horse. The shoes include a pair of Anne Murray's dress sandals, a running shoe worn by Terry Fox, Gaétan Boucher's speed skates, sandals worn by a young Pierre Trudeau, a John Lennon "Beatle boot," and a zippy pair of zebra-striped shoes once worn by Pablo Picasso. The horseshoes? They were once nailed to the feet of Ian Millar's champion show-jumper Big Ben. These and others are behind glass, spotlit in synchronization with a music and voice soundtrack. Nearby bubble cases show shoes of other well-known people. Any vicarious feelings one may have of the importance, ambition, victory, power, or intrigue of the shoes' former owners is heightened by a sound track that varies from strength to sentimentality.

16 From the Star Turns mezzanine one can look back over the entire All About Shoes exhibit and see clearly the layout and display devices that served to energize, surprise, delight, and sometimes distract the visitor from the exhibit content. There are lights, there is sound, there is movement, and there is interaction. Many artifacts are placed in context with small theatre-like sets. These are created by the layering of large cut-out photos of artifact-associated images. Each set is clearly identified with bold tides and delivers a distinct thematic message through bold-type text panels. More detailed text is offered at a smaller type size and positioned consistently and logically below the primary message for each unit. Descriptive labels complete information delivered by text.

17 Text is supplemented by touch-screen multimedia and on-going or button-activated video loops. Sound tracks for videos are offered by handsets and in some instances by open speakers. When the Bata Shoe Museum first opened to the public all sound components in All About Shoes were delivered by open speakers; overlapping sound tracks made it difficult to concentrate on any one portion of the exhibit. The problem was recognized by museum officials and corrected. They turned the volume down. This simple change is a significant improvement to the Bata Shoe Museum experience.

18 Lighting is used well for the most part. Artifact form, colour, and detail are made clearly visible by clean, white, small spotlights within a generally darkened gallery. This sets up a rhythm of alternating dark and light spots that satisfies museum requirements for low lux levels on light-sensitive artifacts, and heightens one's sense of drama and discovery.

19 In addition to illuminating artifacts and text, lights are used to convey a sense of excitement and energy. This is done by the addition of swirling overhead light projections of boot and shoe shapes, and by visitor-operated push-button spotlights. The push-button spodights prompt visitor interaction in the form of button pushing, and they rouse hope of something new coming to light. It is a letdown to find that they only brighten display details that are already clearly visible.

20 Other visitor rousers include trompe l'oeil boxes in the wooden parquet floor and mirrors positioned ingeniously throughout the gallery. Many of the mirrors are placed at foot level and serve to remind visitors of their own boots and shoes. I was startled when I bent down to pick up a pen while standing in front of The Ancients display component. There I saw the reflection of my own winter boots cast in the shadow of a 2 000-year-old mummy footcase. Suddenly my boots were in a dark, chimerical gloom below an ancient tomb artifact. This was a jolt that was momentarily distracting yet served to demonstrate the timelessness of footwear. Overall, the novel display devices serve to entertain without seriously distracting a visitor from the subject matter, and nowhere do the display devices attempt to replace the artifacts.

21 Leaving All About Shoes and Star Tarns one proceeds to the temporary exhibit galleries feeling ready to focus on a particular genre of shoe, or a particular culture as expressed by its shoes. Such focus is indeed offered by the temporary exhibits. As of January 1998, these were Dance! and The Spirit of Siberia.

22 Dance! is an exhibit of shoes styled and worn for social dancing. There are shoes from France, England, and the United States spanning a period from 1730 tol980, moving from the minuet to disco fever. The exhibit displays artifacts in traditional chronological order, but departs from tradition in the use of sound, light, and visuals. The whimsical tone of the exhibit is set by a life-size puppet-like figure who bows in welcome to visitors as they enter, then straightens to ready himself for the next person through the door. A sense of late-night occasion if not the surreal is created by the use of light from videos, image projections, ultra-violet lamps and luminescent paint in a dark gallery. The surreal quality of the exhibit is further advanced by the scattered placement of scrims between visitors and display content, and "spun" wire dancing figures that appear to float above the displays. Sound tracks can be heard if you lean close to listen at tiny speakers projecting from display boards. Kinescopes showing silhouettes of partners in dance offer a low-tech but highly period-evocative alternative to video.

23 A glance at the credit board reveals the character of the multi-disciplinary team assembled to produce this exhibit. Curator Jonathan Walford and exhibit design firm MC2 Design Lab Canada Inc. worked with a team that included such non-traditional participants as an "Electronic Executive Producer" and "Creative Director." Each shoe is well identified, placed in slightly surreal context, and the chronology is easily followed. The narrative identifies various dance styles, their respective periods and influences and the shoes that were used along with the music of each period identified. While the display devices do not attempt to replace the artifacts they do overpower them. For this visitor the display devices suggest that dance shoes are part of a world of fantasy and escape from everyday life. This message, which may have originated with an analysis of the shoes themselves, is carried by the novel display apparatus only, leaving one to wonder at the validity of the idea.

24 From the flight of fantasy in Dance! one lands firmly on frozen ground with The Spirit of Siberia. This is a traditional exhibit in both curatorial approach and presentation, and provides a distinct counterpoise in tone and appearance to Dance! This counterpoise is a good antidote to museum fatigue. Curated by Jill Oakes and Rick Riewe, and designed by Holman Design Limited it presents an ethnographic study of the shoes, and other clothing of several Siberian tribes. It is a temporary installation displaying footwear on loan from the Russian Museum of Ethnography in St Petersburg. Pictures, text, sound, and video outline the tribes concerned, their way of life, the tools and materials used to create their shoes, and the use to which the shoes displayed were put. The importance of the Siberian peoples' spiritual beliefs and their close association with their environment is highlighted in the display. Visitors' attention is drawn to evidence of this importance in the decorative details of the tribal footwear. Decorative symbols evoking prosperity, happiness, protection from revengeful spirits, and good luck in fishing and hunting are noted.

25 Altogether the Bata Shoe Museum exhibits establish the high quality of the collection, its range and diversity, and the importance of shoes as cultural signifiers. They also offer an opportunity to revel in the fantasy that shoes can evoke, and, an opportunity to contemplate shoes as evidence of a particular and remote culture. The portion of the collection displayed in the museum is impressive for spanning many centuries, races, religions, and cultural standards. The diversity of shoes shown is testament to humankind's seemingly endless creativity, ingenuity, and energy when addressing and re-addressing the same basic form century after century. It is truly striking to see that such diverse shapes, colours, forms, materials and uses could be applied to a thing as commonplace as the shoe. But many of these shoes are far from everyday things for most visitors to the museum. Some are obviously unusual, and in many cases valuable for qualities such as rarity, fine materials and craftsmanship, associations with rich, famous, or historically-significant personages, and for the effort, power and skill required to find and acquire them.

26 The value of the collection as material culture is also evident and noted, but it is on this ground that the Bata Shoe Museum could go one step further. The Bata Shoe Museum is an architectural triumph and a welcoming and entertaining place to visit. Its exhibits are finished to high production values, show respect for the value of the artifact as well its care and preservation, and demonstrate a solid curatorial foundation. However, while the intrinsic value of the collection is evident from the museum displays, the value of the collection as material culture is not exploited as fully as it might be. Entertainment, novel display devices, and straight documentation, while pleasing and informative, do not convincingly demonstrate the truth to the premise presented in All About Shoes that shoes carry meaning that can enlighten us about our past and present. Because of this I left with a feeling of want.

27 I would definitely return for an exhibit that would not only identify but also analyse and discuss cultural themes revealed by shoes, as well as the interaction between the shoes themselves and the culture that fashioned them. It would be intriguing to see the ideas and conclusions borne of such an analysis applied to our own culture and footwear. Results from the analysis could be applied to questions like: What are the cultural developments that brought about the current popularity of basketball-style running shoes? Does a pair of basketball shoes bear any relationship to a sporting pair of seventeenth century French fencing shoes? Or is a basketball shoe more akin to an Asante king's sandal? Such a discussion would be a distinctly positive addition to the Bata Shoe Museum and its community.

28 The museum does tread lightly on the grounds of material culture analysis. In All About Shoes we see a chronicling of changes in Western women's shoes through the decades of the twentieth century, and a description of changes in history and social mores that accompanied the fashion parade. In Dance! we learn that shoes of certain types can indicate the social or economic status and moral attitude of the wearer; The Spirit of Siberia notes that the fundamental human need to address spirits and the elements is reflected in shoe decoration. However an in-depth analysis of the interaction of shoes and culture, and the associated meaning of the shoe, would take the visitor beyond the basic recognition that shoes have meaning as demonstrated by All About Shoes, could delve into the meaning of a particular genre of shoe in addition ' to a chronicle and celebration of its use as in Dance!, and could further inform a visitor about the culturally motivating forces that are noted in The Spirit of Siberia. The effects of technological change on the way we think about and use shoes could also be pursued. Perhaps such analysis could be carried out through a series of installations in the Bata Shoe Museum's temporary exhibits gallery. Lessons learned from the series could then be applied to our own culture. We could then feel the benefit of understanding the next time we see our own shoes or boots in a mirror, however scuffed or polished they may be.