Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

The Bank of Montreal Museum

1 Museums, including national repositories of archives, are confronting the reality that acquiring artifacts comes at considerable cost and the likelihood is slim that more than one or two percent of one of these collections will ever be on view at any one time. It is therefore timely to acknowledge the efforts being made by the private-for-profit sector, such as the Bank of Montreal.

2 Not only is the Bank of Montreal preserving its extensive archives, but it is also operating a small (56 square metres) but intriguing museum, which opened in May 1963. It is situated in the hallway between the Bank of Montreal's main branch, built in 1847, and its head office building, built in 1960, both on St Jacques Street facing Notre Dame Church in Old Montreal. Thankfully, I made my visit before the end of March, because otherwise I would not have had the warm welcome from an on-site guide. Unfortunately, like so many other museums suffering through belt-tightening, this position is being eliminated.

3 The Bank of Montreal is not the only corporation to show an interest in preserving and rendering accessible artifacts of national importance. Bell Canada had a museum until very recently, and still maintains its extensive archives. Hydro-Quebec has a floor devoted to its archives. Canadian Pacific has an archives open to the public and located in Montreal's Windsor Station. Molson Breweries has maintained an archives, as have the Eaton company, B.C. Sugar Refinery, and Redpath Sugar.

4 Clearly, the original impetus may not have been to preserve what they felt would become significant or of national importance. Rather, it was probably due to a large corporation's documentation policies and a need to limit access to potentially sensitive materials. Only later, when sufficient time had passed, was it realized that their corporation's history was inextricably linked with the history of our nation, and therefore worthy of preserving. In the introduction to Merrill Denison's Canada's First Bank: A History of the Bank of Montreal, published in 1965, the bank's chairman and president wrote: "In presenting this work as the history of a single institution, we commend it also as a wide-ranging story of Canadian achievement."1 In the Bank of Montreal's Business Review published in 1967 it was written: "Many of the highlights of the Bank's progress have been associated with important milestones in the development of the country, so that the history of the Bank of Montreal is, in many ways, a reflection of the history of Canada itself."2

5 The indisputable fact that the Bank of Montreal is Canada's oldest banking institution, having been founded in 1817, is reason enough for them to devote a museum to its origins. A re-created office of the Bank of Montreal's first cashier greets visitors appropriately to the museum. While undoubtedly some artifacts, including the grillwork and ledgers, are not reproductions, it is difficult to tell which are and which are not. This is not an unusual problem found in the best of today's "professional" museums, including the Canadian Museum of Civilization, and is certainly not insurmountable, through a labeling system. The wonderful ambiance achieved through such a re-created period room is not undermined with good, solid labeling, but enhanced through communication on more than one level.

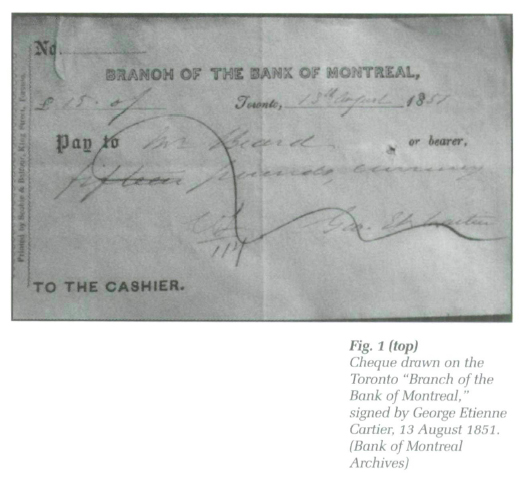

6 The history of the Bank of Montreal, originally the "Montreal Bank" until it was granted a charter in 1822, is also fascinating from the standpoint that it was involved in the financing of such projects as the Lachine Canal, early steamship navigation through to the Great Lakes, the Grand Trunk Railroad and Canadian Pacific's transcontinental railway. Donald Smith, later Lord Strathcona, vice-president of the Bank of Montreal, hammered into place the last spike of the railway in 1883 in the Rockies. In the museum, these "mega" projects are displayed in three-dimensional, wall-mounted shadow boxes consisting of now out-dated reproductions. In fact, this installation dates from the early 1970s, and also includes classic 1970s glass-topped showcase furniture in which authentic artifacts are displayed. Most of these artifacts consist of bank notes, including a rare example of a $3 bill from 1944 (one of two known to still exist) and a cheque inscribed on the back of seal skin from 1933, as well as a note signed by George Etienne Cartier in 1851 (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, the deep cases are for the most part poorly lit, and as a result hinder the visitor's ability to decipher the lovely nineteenth-century handwriting.

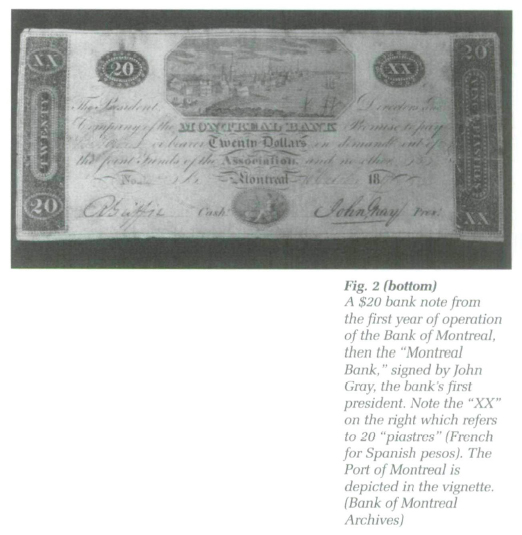

7 Other bank notes on view communicate the fact that the Bank of Montreal had issued notes since its inception in 1817 (Fig. 2), a role played exclusively by the Bank of Canada today, and had served as banker for the federal government since 1867. The Bank of Canada was formed in 1935 following the Great Depression in 1929 and in response to a need for a central monetary policy. In 1935, the Bank of Montreal was given fifteen years to retire circulation of their notes, and was no longer the government's exclusive banker.

8 A selection of black-and-white photographs is also displayed in small snapshot format in another floor-standing, glass-topped cabinet. Many depict branches of the Bank of Montreal in remote locations across Canada, including Castor, Alberta (Fig. 3), Elliot Lake, Ontario (Fig. 4) and Kelliher, Saskatchewan. The buildings varied from trailers to sheds! The modest beginnings of some of these branches is somewhat refreshing. What did we expect, instant classic stone structures that spoke of riches? Furthermore, many of the photos are worthy of being exhibited in a more prominent fashion, because they have high artistic merit in addition to being of documentary value.

9 Unfortunately, stories of pioneering bank managers such as Arthur Buchanan, who had to travel by snowshoe the last fifty miles to open a branch in Nelson, B.C., early in 1892, are not present in the museum.3 On another level, when you consider the proliferation of branches through the acquisition of smaller banks by the Bank of Montreal, one has to feel that the Bank of Montreal played a unifying role in the creation of Canada in a way similar to the construction of the transcontinental railway.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 210 From the display, you unfortunately won't learn either about William McGillivray, a senior partner in the fur trading North West Company, who had to declare bankruptcy in 1826 with the decline of fur trading. "The McGillivray debt to the Bank stood at close to $90,000, at a time when the Bank's total assets amounted to about $1.6 million, and it was as a direct result of this and a number of similar but less costly insolvencies that the Bank, in 1827 and 1828, failed to declare dividends for the first and last times in its history." To leam that the bank has not always had it easy would be good public relations today for any bank, often criticized for making excessive profits.

11 The Bank of Montreal has had a history of commissioning Canadian artists, including Nicholas de Grandmaison, to paint portraits. A large format book of Grandmaison's native portraits was even published by the bank and is available for consultation in the museum.4 Sadly, not one of these are on view in this museum. It makes one wonder what other treasures have not been selected for display.

12 Tools of the trade, including an early mechanical pencil sharpener and typewriter, are displayed; however, there is little indication of the important role they must have played in advancing the bank's interests, let alone of the strong possibility that banks may have been among the first businesses in Canada to equip themselves with state-of-the-art technology.

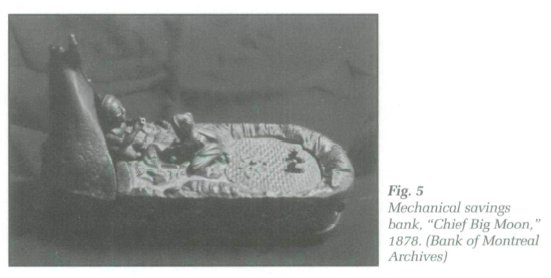

13 A wonderful selection of cast-iron mechanical penny banks from the Bank of Montreal's collection has also been temporarily put on display (Fig. 5). The installation is marred by the fact that some of the examples are of recent manufacture (why bother including these?), and all will disappear along with the guide, because they are at risk in an unmanned display. In fact the whole museum will lose a lot of appeal without the human presence. Not only was the interactivity wonderful for children, as they were shown how the mechanical penny banks worked, but also for the informed; the guide supplied supplementary pertinent information when labels were lacking (which was too often the case).

14 Sadly, with the loss of the guide and too much reliance on reproductions, the museum as a whole will suffer. In fact another more recent installation consists solely of reproductions of promotional flyers mounted in collage fashion. While at closer inspection it becomes evident that "My Bank" was a recurrent promotional theme for an extended period of time in which a dog was used to suggest loyalty, this fact is lost in the indiscriminate selection. Weak installations of this sort are also lost opportunities for the bank to do some good promotion work. It would take only a small portion of a publicity budget to have quite an impact when you consider that the museum apparently attracts an annual attendance of nearly 20 000 visitors.

15 Outreach display work is also ongoing throughout the bank's network and is for the benefit of employees as well as clients. An example is the display case in the main branch. It consists of Bank of Montreal related artifacts donated back to the bank. It is a tribute to the bank's customer service being reciprocated. One intriguing item is a silver dog collar that was given by the Bank of Montreal to a customer in 1893 for "services rendered." It was returned to the bank by the customer's descendants now living in England. The label, however, unfortunately doesn't elaborate on the story. Was it really for a dog?

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 316 Nevertheless, in this day and age of fiscal restraint, it is difficult to find fault with a profit-oriented corporation which neglects to maintain or improve a museum, when they are already preserving for future generations an acknowledged rich cultural resource of national importance. Rather, is it not a viable option to ask that the government encourage private sector endeavors of this kind by either matching grants or by tax credits, so that these small but wonderful efforts may continue?

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 517 Those of us in larger institutions who enjoy some government subsidization know only too well the impact of acquiring artifacts. They come at great cost and with no guarantee that they will ever go on view. Maintaining intimate corporate museums of this sort, even if they only provide a sampling of their rich archives, is a tribute to their modest beginnings and the personalities of the individuals who founded these corporations. The Bank of Montreal must be congratulated for its efforts!

I want to thank the Bank of Montreal's Yolaine Toussaint, archivist, and Lucie Vézina, animator, for their kind assistance in the preparation of this article.