Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

Clothing in Two Acts

Sponsor: Mulberry, British designers of clothing, luggage, leather goods and a home interiors collection

Curator: Amy de la Haye

Duration: 6 March to 27 July 1997

Publication: The Cutting Edge: Fifty Years of British Fashion, 1947-1997. Ed. Amy de la Haye. Woodstock, N.Y.: Overlook Press, 1997. 224 pp., cloth $50, ISBN 0-87951-763-8.

Sponsor: Parfums Christian Dior (UK) Ltd and the Association for Business Sponsorship for the Arts

Curator: Angela Godwin

Designer: Imperial War Museum in association with Peter Leonard & Co.

Duration: 12 February-31 August, extended to 2 November 1997

Publication: Forties Fashion and the New Look. Colin McDowell. London: Bloomsbury, 1997. Cloth $39.95, ISBN 0-7475-3032-7.

1 It is precisely because clothing is so ubiquitous, and because humans are generally so aware of how powerful a reflection of individual and social persona clothing can be, that historians of material culture find costume and fashion such potentially rich artifacts to explore. In London, England, last summer, two museums dedicated space to such projects on clothing, and both the Victoria and Albert's The Cutting Edge: Fifty Years of British Fashion, 1947-1997 and the Imperial War Museum's Forties Fashion and the New Look were substantial in their own right. Overlapping only minimally in focus and content, they represent two distinct ways of approaching the study of clothing — one using a more traditional methodology and confining itself to studying the "best" in the field, arguing its thesis almost exclusively through the actual dresses, shoes, and underwear it presented for view, and the other gearing itself to a more holistic approach to popular culture, relying on a great variety of cultural artifacts to state its case.

2 The Victoria and Albert Museum's The Cutting Edge, on display between March and July 1997, was deliberately upmarket in its selection and presentation of themes and costumes. Including both men's and women's fashions, it was intended as a "unique opportunity for fashion students, victims, and style gurus alike to view a spectacular ensemble of British fashion at its very best." The exhibit was sponsored by Mulberry, an English company that sells men's and women's clothing and leather goods, in a mutually gratifying arrangement since at least one Mulberry product was exhibited. Based on the premise that London, rather than New York, Paris, or Milan, was at that moment the most significant hotbed of haute couture, the exhibit sought to promote the designers that made it so, and consider the characteristics that gave British fashion its distinctive and respected identity.

3 This is a premise that, in its own context, has some justification. British couturiers have indeed been making their names in the international fashion world, and have infiltrated, by invitation, the sacred space of the French fashion houses: Alexander McQueen was hired as principal designer at Givenchy, John Galliano at Christian Dior, and, more recently, Stella McCartney (daughter of Beatle Paul) recruited to Chloe.1 Savile Row tailors are the benchmark of discrete, high-quality, perfectly cut men's fashion. But perhaps the strongest generator of interest in English fashion was the limelight borrowed from one of its advocates. Before her death, the Princess of Wales was arguably the ambassador of choice in disseminating awareness of British couture throughout the fashion world: as a Royal, she had been committed to wearing the designs of her national compatriots to public functions.

4 The disappointing aspect of The Cutting Edge, however, derives from the inherent assumption that underscores the exhibit, that "designer-level" style and "British fashion" are equivalent. Untrue to its name, this is not a trend-setting exploration of the impact between fashion and culture in the sense that it did not venture beyond the mainstream chic of the fashion magazines, did not walk the streets or bars or countryside to discover what the majority of its citizens wear, did not consider the impact of its multicultural and therefore multi-clothed population.

5 Moreover, it ventured little to add context to the clothes by showing them as and where they had been worn, except by captions that identified the designer, sometimes named the wearer and the occasion and, rarely, added brief information concerning some isolated aspect of the design process. And, although it is difficult to think about couturier fashion now without considering the negative repercussions on self-image — here, too, the Princess's famous confessions about bulimia are called to mind — no such considerations were encouraged here to threaten the feel-good tone.

6 The Cutting Edge grouped British fashions into four distinct themes, and this quadripartite division gave the exhibit its structure. The approach was formalist, inviting comparisons of different styles at different times. New wave-type music set the mood, along with dim lights: the effect was demonstrated by the hushed tones of the viewers. Mannequins , some headless and others having what looked like blindfolds over featureless faces, were mounted on platforms that created a psychological distance between the artifact and the viewer, for whom, in many cases, the inaccessibility of costumes of this price range had already established such a gap.

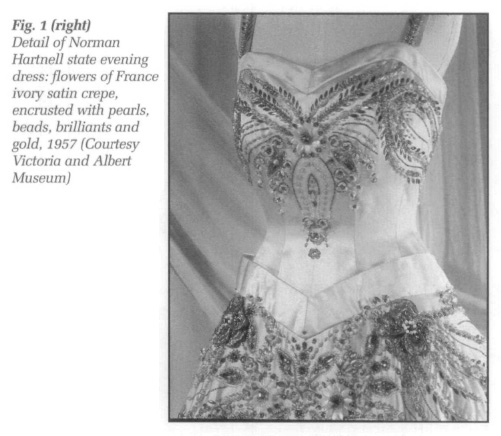

7 The first section, entitled "Romantic," furthered the glamorous ambiance by displaying the most fairy tale of the dresses, and alluding to (if not actually giving a sense of) the world of the debutante, the season, the society wedding. Represented here, for example, was the work of Norman Hartnell, who received the Royal Warrant in 1938 and was responsible for Queen Elizabeth's coronation gown. Here, too, was an enigmatic debutante gown of 1994 by Vivienne Westwood: bedecked with pearls and obviously inspired by eighteenth-century rococo, its otherwise saccharine adherence to traditional monumental extravagance sharply contrasted by what was alluded to in the caption as a modern concession, a shredded tulle skirt that evokes Cinderella before the arrival of the fairy godmother. And, perhaps at the most campy end of the fashion spectrum, a Zandra Rhodes gold metallic extravaganza from 1981 gave momentary pause from the pomp and circumstance by suggesting a synthesis between Attila the Hun and Barbie. The Cutting Edge may have had a limited scope, but was not without its sense of humour.

8 The exhibit did, on rare occasions, serve as a beacon beyond the confined realm of the pampered set. Two dresses in the Romantic section were particularly interesting in this regard. One, a Hardy Amies 1947 brown-and-white creation, was a response to British government promotion of the post-war cotton industry, of cloth made in Manchester for the West African market. Its three-quarter length was a reminder of the residual effect of clothing rations that continued for four years after the war. The second, a 1947 Rima evening dress of printed rayon crepe, was presented as an example of the difficulties of producing high-quality fashions after the war, because of the lack of satisfactory fabrics and dyes. In both cases, the focus widened, albeit slightly, to call to attention a fascinating range of issues, including the link between the fashion industry and other economic factors, and the role of technology on design production.

Display large image of Figure 1

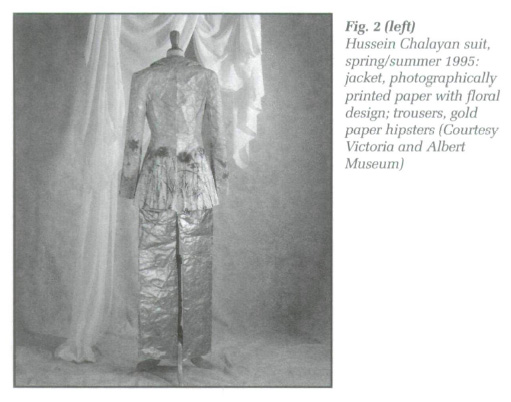

Display large image of Figure 19 The other three categories were entitled "Tailoring," "Bohemian" and "Country," and they contained surreptitious treasures. A Mary Quant "Tutti Frutti" grey flannel tailored suit of 1962 was presented as an example of a very popular trend, but called attention to itself because of its size, larger than the petite norm. Amidst the Laura Ashley-type flowery frocks in the Country section was a 1995 Hussein Chalayan suit, out of green and gold polyethylene that looked like crumpled paper — a suggestion of the exploration of new materials. The Bohemian category included a 1986 cape by Rosemary Moore entitled "African Mask," originally created for an exhibition of wearable art shown in London and Japan. A fabulous negation of body within its formless embrace, it invited musings on post-colonial-related issues.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 210 The Cutting Edge, then, was not without its faults. It was frustrating to see such riches and have little clue about the men and women who made these dresses, whether the garments were hand- or machine-sewn, made in Britain or elsewhere, whether they inspired cheaper versions for wider audiences. It would have been interesting, for example, to chart one design and see how it translated to a paper pattern to be used by the home seamstress, or knocked off, or was worn by people in then-daily lives. One can imagine tracing how the Chanel suit inspired many iterations of itself: a Mary Quant little black dress of the late 1960s, which appeared in this exhibit, would have been an excellent subject for such a study. Welcomed, however, were some of the attendant bonuses of the exhibit. These included a project entitled "Out of the Closet, into the V&A," whereby the public was encouraged to donate used designer clothing to a charity shop in return for free admission to the exhibit; a lecture course with guest speakers, including Mary Quant and Alexander McQueen; and two displays elsewhere in the museum, Fashion on Paper, of sketches by eminent designers; and Contemporary Fashion Photography, which focussed on the period 1987 to 1997.

11 While the Victoria and Albert made the clothing itself the primary speaker, such was not the case at The Imperial War Museum's Forties Fashion and the New Look, on display until November 2. Here, the British 25 Pounder Quick Firing Gun Mark II and the Bibber German One-Man Submarine in the central exhibit hall automatically contributed contextually; within the confines of the Forties Fashion exhibit space, artifacts of many types, a large portion of which were lent or donated from museums as well as from private donors, were presented. Thus, actual clothing vied for attention with advertisements, taped interviews, newsreel footage, films, radio programs, music, makeup, furniture, and mementoes such as a tin money holder and its contents fused together after a firebomb hit the John Lewis Department Store on Oxford Street. The result was an exceedingly rich foray into the world of England before, during, and immediately after the Second World War, told from the perspective of the clothes that people wore. This exhibit was a clear demonstration that the value of studying clothing lies not only in the opportunity to learn about the garments themselves, but in the chance to understand their central role in determining, disseminating, and reflecting their culture broadly writ.

12 Forties Fashion was arranged thematically within a general chronological framework. Its artifacts were at some points presented in synthetic settings to reproduce the environment from which they derive, an unnecessary effort, given the demonstrated ability of the objects themselves to create and carry the narrative. At the entrance was a photo of Wallis Simpson wearing Schiaparelli's Lobster Dress of 1937, inspired by Salvador Dali and photographed by Cecil Beaton. Capturing a sense of frivolity and decadence, it was a perfect foil for what lay ahead. Similarly, a section on "Phoney War fashions," addressing the early stages of the war during which no serious action took place, included a 1939 Vogue magazine's pronouncement that to be au courant, one must choose just the right bag in which to carry one's gas mask.

13 The impact of the war was shown through a number of operative themes. In a section entitled "Fashion Takes Cover," clothing became the symbol of the terror of hearing airplanes over London during the blitz. For example, women's shoes at the Café de Paris nightclub, which suffered a direct hit in 1941, poignantly carried the image of destruction and devastation.

14 On another tack, two sections, "Fashion on the Ration" and "Make Do and Mend," explored the multiple repercussions of the restriction of fabrics and garments for the war effort. A central artifact here is the ration book that governed family purchases, and challenged the resourcefulness of Britons in overcoming this obstacle. As of June 1941, each person received sixty-six coupons per year, reduced to forty in 1943; this translated to less than half the number of garments available to an individual for purchase, as compared to before the war.

15 The diversity of related objects in these two sections was substantial. There were posters ordering the public to "make war on moths," a culprit about which our own age and culture have relatively little concern, and to "plan ahead — allow for growing" when making clothing purchases for children, a far cry from the encouragement to commodify with which we are now familiar. The museum's sound archives were used to advantage, in this case with an account given by a woman of how her friends struggled to fulfil her dream of seven yards of fabric for her wedding dress, requiring fourteen precious coupons. In an attempt to encourage the public to extend the usefulness of garments to the greatest degree, the British government invented a fictional character, Mrs. Sew and Sew, to offer advice, and her leaflets, magazines, and radio programs are included in the exhibit to convey the allpervasiveness of this campaign.

16 A dual purpose can be read in this strategy. At an obvious level, the public was being instructed to be scrupulous in not wasting a valuable commodity. Equally important, however, was the message sent to make old, reconstituted, perhaps shabby clothing socially acceptable, to see sacrifice as necessary for the war effort, to equate frugality with patriotism. The relationship between clothing and nationalism was thus profitably explored, as it was also considered using more bizarre artifacts such as a dressing gown made from fabric printed with patriotic quotes from Shakespeare's Richard II and a series of Jacqmar scarves with wartime slogans such as "Salvage your rubber." Emphasized through the objects was the all-encompassing hardship of the Second World War — although fought primarily elsewhere — the fact that, in addition to endless concerns for loved ones in the battlefields, for individuals' own safety during the bomb attacks, the war meant a continuous struggle over such mundane and basic needs as dressing and feeding a family.

17 The significance of British war clothing outside the country, and beyond the war, was considered in two sections, the first entitled "Utility." It presented a range of clothing, including underwear and footwear, and fabrics made in Britain according to the strict specifications of the Board of Trade. In collaboration with such designers as Hardy Amies and Norman Hartnell, both of whom were represented at the Victoria and Albert exhibit as well, the board advocated designs based on a restricted use of materials and ornamentation, designs that reinforced the trends even of countries such as the United States and Canada, which did not have rationing. Utility clothes were manufactured as late as 1952, and are given credit as having introduced standard sizing. The second section, "Export or Die," considered the reliance of the British economy on the fashion industry as helping to finance the war effort, further widening the focus of the exhibit.

18 Perhaps the most interesting section of Forties Fashion was devoted to glamour, even as it brought to light what must be considered as the most significant absence in the exhibit. During a period that condemned wastefulness, glamour — specifically the use of resources for purely aesthetic, self-gratifying means — played a fundamental role in compensating for the sacrifices and raising morale. When Yardley, the cosmetics firm, was converted to produce aircraft parts, women used products made to darken gravy to colour their legs. Elaborate hairstyles, requiring few resources, dressed up utilitarian clothing. Putting colour back in one's life appears to have been a dominant theme: an advertisement for face powder by Coty apologizes to its buying public because its powder puff can no longer have a multicoloured motif. Films of Hollywood stars were shown in this section to heighten the sense of escapism.

19 But perhaps the most effective artifact to demonstrate the power of glamour was a blue negligee made in 1943, using coupons earned in exchange for free hairdressing. Made specially by one woman to wear on her husband's return from a secret mission, its effect, we were told in the characteristically chatty captions, was substantially diminished when he arrived early, to see his spouse in hair curlers and old pyjamas. This view into the hopes and thoughts of one person, seen in terms of one cultural artifact, was a rare privilege.

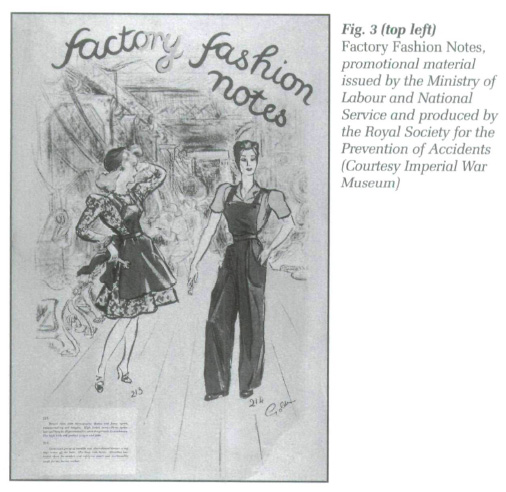

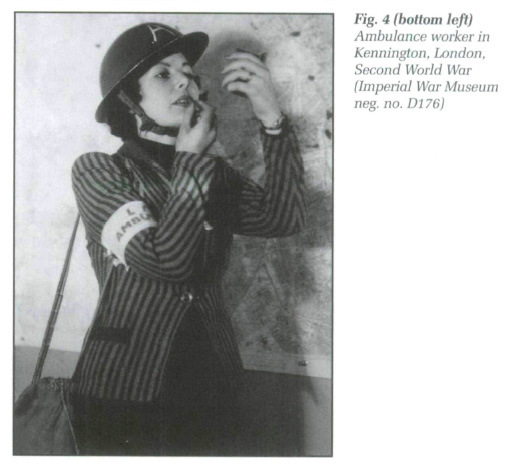

20 Unfortunately, in paying such attention to glamour, Forties Fashion made it all the more obvious that one key aspect of the relationship between war fashion and women had not been given sufficient consideration. Cultural historians have often remarked on the war years as witnessing the increasing popularity of pants worn by women, both for practical reasons — safety and comfort in factories and on the land; as a means to cover legs for which nylon stockings were not available — as well as for other more symbolic reasons associated with the connotations of doing work previously designated as appropriate only for men. An interesting example of such non-feminine dressing was a photograph of Princess Elizabeth in her uniform of the Auxiliary Training Service. Other images, such as that of a woman in overalls working in a factory, showed women dressed unconventionally. However, given this water-shed in the transformation of gender roles, and notwithstanding the fact that postwar clothing generally reverted to a much more feminine norm, a whole section on gender issues related to clothing and the war would have been most welcome. Indeed, it would have given balance to the glamour section, and prepared the observer for a composite image of women during the war, such as that of the ambulance worker in Kennington, whose lipstick is entirely compatible with her hardhat, symbol of her non-gender-specific job.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 321 It was during the presentation of postwar clothing that a shift took place in Forties Fashion, one that became clearer after taking into account the more internationally-oriented perspective of postwar fashion design. During the war, the significance of local circumstances prevailed — restrictions on materials, government incentives, a shared sense of responsibility concerning the war effort. Once the war ended, rationing in Britain continued as a result of a poor economy and the loss of American war loans. In France, however, designers struggled to re-establish themselves as fashion leaders. One in particular, Christian Dior, is singled out as instrumental in 1947 in creating a New Look, fundamentally opposite to that which had predominated during the war. Expensive, and requiring substantial amounts of fabric — in some cases approaching twenty metres — his dresses were decidedly and deliberately elegant, and meant to be worn with corsets, high heels, smart hats, and perfume. Public reaction was divided, in England as well as in the United States, where the extravagance was condemned by some, and welcomed as a tangible sign of new and better times by others. Significantly, Christian Dior, a French fashion firm that happens now to have British designer John Galliano as its head, is listed as the corporate benefactor. This might help to explain why the exhibit's range swept across the Channel, and ended by focussing so heavily on the work of one Paris house. There is no denying, however, the impact of French postwar design, especially given the inclusion in the exhibit of British responses to the New Look by Hardy Amies in 1948, and Victor Stiebel, both British designers.

22 In any case, Dior does not succeed in stealing the postwar show. If anything, his precious designs were shown up by the continuing ingenuity of the British public, in finding ever more imaginative ways of satisfying their clothing needs in spite of continued rationing. One of the most wonderful successes was a graduation dress of 1947, sewn from a Vogue pattern. Made of a silk parachute, it cleverly also used the cords of the parachute for shoulder straps. In another instance, a wedding dress worn by Gwynneth Harrison at her marriage to Lionel Brown in May 1947 was fashioned by a local dressmaker who used surplus mosquito netting for the skirt, and the sleeves from the bride's great grand-mother's wedding dress. The cover of the promotional pamphlet of Forties Fashion may highlight a Dior bar suit, but the residual impression of the exhibit rests with these truly unique specimens.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 423 The success of an exhibit clearly lies in its ability to fulfil its mandate, to use artifacts to address the thesis it chooses to present. But the treat of a presentation such as Forties Fashion rests also in its ability to stimulate the ideas of the viewer based on his or her own research interests, and there is much here that would prove worthy of examination. For example, many artifacts in the exhibit suggested that the rationing problems and make-do-and-mend projects were the domain and responsibility of women, administered by men who were government bureaucrats, designers, etc. One photograph in the exhibit depicted women protesters seeking signatures for a petition against additional ration cuts in 1946. Was this an isolated occurrence, or routine? Was rationing perceived as a gender-specific issue? Did this protest spring from a new-found freedom to challenge gender roles? Such questions were not directly addressed in the exhibit, but they spring from the artifacts on display.

24 With a few reservations, then, the Imperial War Museum is to be congratulated for the breadth and range of this memorable experience, in capturing a strong sense of the life of Britons during the war years as told through their clothes. Non-elitist and inclusionist in its approach, this exhibit was in keeping with the priorities and aspirations of a material culture methodology. By keeping the spotlight squarely on artifacts as conveyors of information and, through the captions, filling in the gaps with historical and contextual information to establish the necessary perspective, Forties Fashion had much to offer for layperson and scholar alike.