Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

Canadian Museum of Civilization, The Painted Furniture of French Canada, 1700-1840

Duration: 29 May 1997 to 15 March 1998

Publications: exhibit texts, soft cover spiral-bound in English or French, 49 pp., approximately 60 illustrations, mostly black and white sketches, $5 (Canadian Museum of Civilization)

Book: hardcover in English or French, with the same title as the exhibit: Camden East, Ont.: Camden House Publishing and the Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1994.179 pp., $34.95, ISBN 0-921820-85-2. (See book review by Edward S. Cooke Jr, Material History Review 44 (Fall 1996): 134-5.)

Exhibit Internet site: http://www.mvnf.muse.digital.ca (museum home page) and http://www.mvnf.muse.digital.ca/expos/meubles (furniture exhibit)

Exhibit Team: Senior Interpretive Planner, Jean-Marc Biais; Guest Curator, John Fleming; Designer, Dalma French; Project Manager/ Co-ordinator, Danielle Goyer.

1 The Canadian Museum of Civilization presents us with a multi-media exhibit extravaganza rooted in guest curator John Fleming's research on French Canadian furniture. The focus of the exhibit, named for Fleming's book published three years ago, invites discussion about how painted furniture has been treated by past generations and how we should now protect it. Fleming is primarily concerned with the aesthetic value of French Canadian furniture, that is, its appearance according to shape and line, form and finish. Those familiar with Fleming's book will not be surprised to hear that the exhibit format consists of a veritable parade of beautiful objects. Therefore, visitors expecting to view fine French Canadian furniture up-close-and-personal will not be disappointed.

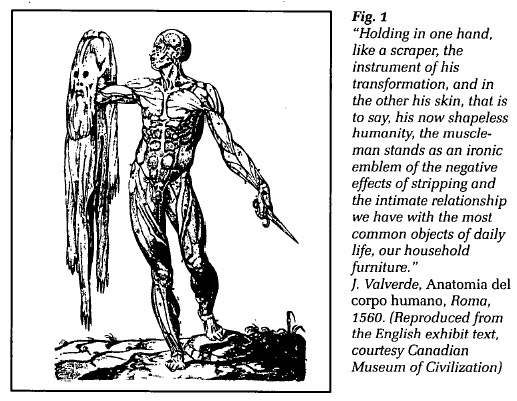

2 The most meaningful, but by no means new, message of this exhibit is that furniture despoiled in the past has prevented insights into our French Canadian material heritage. A1560 European print of a "skinned muscleman" sets the tone for the exhibit (Fig. 1). The implication is that furniture, like humans, can be "led to the slaughter" by stripping, exposing the internal form to degradation by removal of much-needed outer layers. The most valuable furniture aesthetically then becomes the virgin chair, table and armoire: that which has been least tinkered with, unsoiled by the touch of many hands, and retains as much of its pristine youthful and original appearance as is possible. Of course, like virgins, these items are rare.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 How do we deal with furniture that has been so adversely affected? Guest curator Fleming appears to be in the "leave it be" school. Today, furniture has to be preserved for the enjoyment and benefit of future generations. Yet just how this is to be achieved is not entirely clear from this exhibit. While Fleming would have us keep the object as it now appears, other viewpoints are presented. For example, another perspective is introduced by conservators whose livelihoods depend on improving the condition and, by default, the appearance and beauty of such objects. Within the exhibit, resident conservators actively remove layers of grime and rework objects, like plastic surgeons working on aging Hollywood stars. Here we have an alternative approach: perhaps it is better, under certain circumstances, to attempt to return furniture to its original condition, stripping away the layers of time, refinishing to an original colour, repairing incongruities, and inserting replacements for worn-out or missing pieces. Such furniture, like a rejuvenated person, is more easily presented and displayed, not just in public spaces but in home settings too. Within museums themselves these wares are less likely to languish hidden away as study items and "has-beens."

4 However, these two views embodying curatorial and conservationist perspectives ("leave it be" and "do it up") may differ from those of dealers catering to a vast array of collectors' needs. Indeed, another option appears in dealer advertising within the exhibit texts wherein advertisements offer furniture for sale in both "refinished and original condition." Another vendor specializes in "repairs and refinishing," the latter listed on the same page in the exhibit text on which the conservators' work is discussed, perhaps leaving us with a (false) museum stamp of approval. This permits the image that anything can be done, given certain taste and pocket limitations. Perhaps this is what the clientele desires but is this the message the exhibit planners want to send? The exhibit itself is thus multifaceted (and inadvertently disjointed) according to who is writing, performing, or advertising versus reading, watching or buying. The guideline promoted by guest curator Fleming is one of moral restraint and conservatism. The conservation team at this particular museum is more concerned with stabilization then returning items to their former glory. Alternatively, the dealer will most likely provide anything necessary to sell the item. In essence, the overall conservation question becomes "How far would you go?"

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

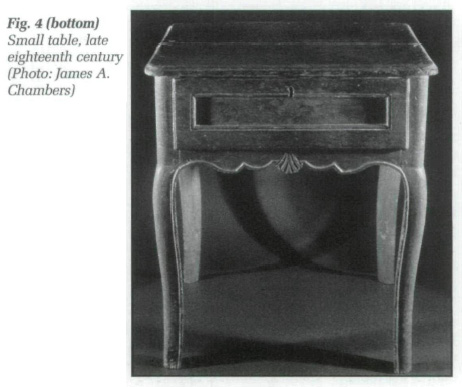

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

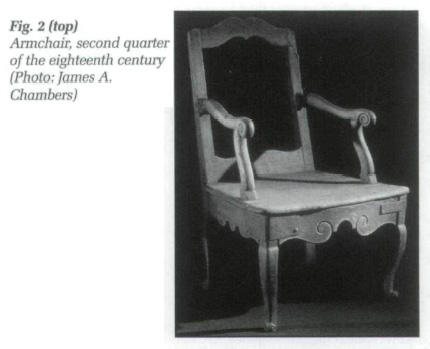

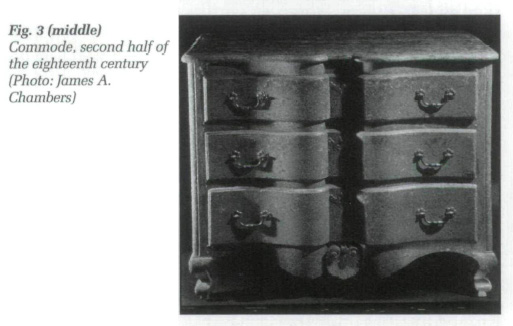

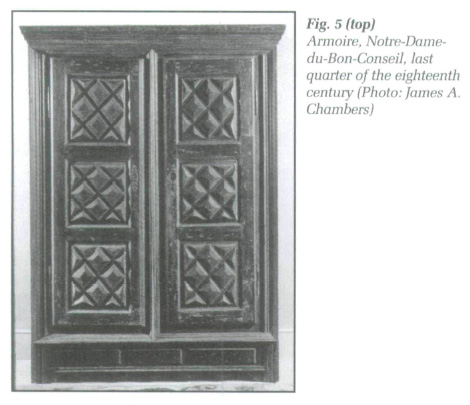

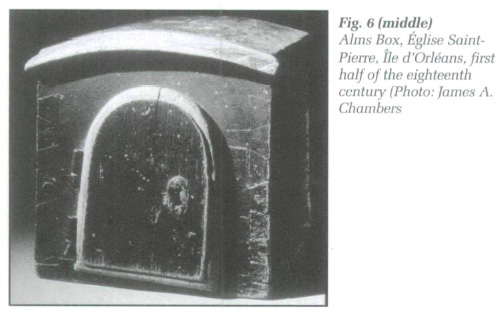

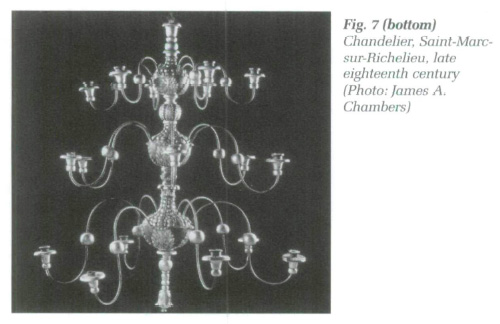

Display large image of Figure 75 Nowadays museums and their curators are striving to be politically correct by presenting inoffensive and relatively uncontroversial exhibits. This exhibit continues in the same vein. There is no discussion of French Canadian furniture making traditions within an ethno-historical context, for example. Within a Canadian context, where does this furniture place within a bilingual, multicultural nation? What interaction was there between French Canadian cabinet-makers and their English Canadian counterparts at different points in time? What impact did the Conquest have on designs and marketing? Were the American loyalists more influential than the British in the post-conquest period or did no anglophone cultures have any significant impact? Were any construction techniques exchanged between cultures? Are there any extant examples of furniture mingling styles, for example, are there Chippendale back-splats used in conjunction with French Canadian sloping arms on individual chairs? Even dire differences between francophone cultures are not compared. Is French Canadian furniture any different from Acadian? These are not necessarily easy questions to answer but if this exhibit had focussed on anything other than aesthetics, we may have learned something new and exciting. Indeed, exhibits should be more than parades of objects with limited interpretation (Figs. 2 to 7).

6 Inevitably, the professional furniture historian is left asking, "Has this exhibit moved the learning curve forward?" Apparently not, given what Edward S. Cooke Jr has already pointed out. For here, as in the book, there is no systematic or rigorous analysis of context of production and use, no development of an interpretative argument, and no explanation of the furniture craftsman's world. Divorced from politics, this show offers limited, if any, discussion of Anglo-French interaction. Indeed, these items are presented without any national or international definition. The furniture is thus presented devoid of context and meaning.

7 Variety is achieved in the presentation of these more than seventy colourfully painted furniture items by sideshows. There are two featured exhibits that cause the visitor seeking a quick fix of colourful artifacts to stop and take pause. To begin with, in the first corridor there are reconstructed interiors: the auction room and salon. Projected shadows of people cast against the salon's back-wall mesmerize temporarily. This "room" is filled with period furniture (old or reconstructed, historically accurate or not, is difficult to make out without aid from the text in this dimly-lit room). The purpose here is to reveal prestige in a display of acquired goods; such fortunes in ages past transferred readily by means of the estate auction and gambling table. This does not exactly fit in with the conservation of painted furniture theme in the rest of the corridor, however.

8 Secondly, in the next side-room is a conservator-animator. On this particular day a junior museum employee works diligently restoring painted surfaces on a French chandelier, using another contemporary example for colour palette inspiration. A side chair thickly coated in paint sits patiently awaiting attention ("stripping?"). Visitors are encouraged to ask questions, and any information not readily at hand is sent out at a later date. It is possible, for example, to find the name of a cleaning material and its German manufacturer's address.

9 In a way, these sideshows detract from the guest curator's message — as the grandeur of painted furniture from private and public collections is left behind in less well-lit, static displays against uninspiring back-walls. On the other hand, these activities reinforce the message: the study of our cultural history represented within our furniture heritage reveals our past lives and is worthy of prolonged personal study and professional attention. Also, these entertaining shows appeal to a more diverse audience, not just those who collect but those who would restore and reconstruct. Co-ordinator Jean-Marc Biais scores on this point. Not only has he ensured that conservation practices are considered, giving an insight into museum behind-the-scenes functions in the process, but he has also co-ordinated four weekend workshops to guide collectors in dealing with the art of selecting and preserving old furniture.

10 From a museographical perspective, this is logistically not an easy exhibit to get around. Difficulties in the visitor flow pattern are generated joindy by immobile architectural features (which must pose problems for any exhibit held here) but are unnecessarily reinforced by the accompanying texts. There are four corridors or exhibit spaces within this gallery. Moving down the first corridor with stripped furniture in it, at the right of the entrance, the visitor passes by the interior reconstruction and conservator to the rear of the gallery (label/catalogue text A-G). The visitor then continues following a U-turn into the central corridor (label/catalogue text H-L), which promptly returns him back to the entrance. Then, turning to the right, a third corridor is reached. But, in order to continue the text line, it is necessary to go to the end of this corridor and turn around 180° before recommencing the text on the way back again to the entrance (label/catalogue text M-S). This is not the end of the story, for it is necessary to then go back again to the rear of any of these three corridors, where chairs and a video have been missed in a fourth exhibit area. Feeling dizzy yet?

11 Apart from the first corridor already discussed, the middle corridor features figurai painting, faux-bois graining, light/bright colours, and plain-painted furniture. These objects consist of visually and aesthetically pleasing pieces. The third corridor highlights examples of wood, mortise-and-tenon joints, paints and instruction books, a carpenter's account from Montcalm House work,fixed-in-place and movable furniture, a print of L'Armessin's grotesquely costumed cabinetmaker, and finally "domestic and common things." Many of these are such broad topics they are not dealt with in sufficient depth, especially given limited space considerations. Finally, at the back of the corridors is a gallery featuring chairs on podiums and, finally, a video.

12 Exhibit texts are available to accompany your tour. These consist of spiral-bound photocopied pages laid behind a top sheet duplicating the blue chair previously featured on the book cover (Fig. 2). There is only one additional colour page in the entire text, featuring poorly reproduced wood grains. Not a single item of painted furniture is featured in colour. Mediocre line drawings are included instead. Surprisingly, a full-page advertisement appears at the very front of the text for an antiques newspaper and, later on, for furniture dealers and refinishers.

13 The content of the text is marred by terminology and glossary problems. This results partly from inadequate translations from French to English linguistic traditions. John Fleming, as professor of French literature at the University of Toronto and as part of the interpretation team, tries his best with a topic that has long bewildered professional cataloguers working in only one language. To have to deal with translation doubles the writing team's task. When comparing French and English exhibit texts, in some instances the French is not translated into English at all (for example, definitions of "la traverse" p. 9, "le bâti" p. 17, "montants" p. 38). Conversely, references to English furniture publications, such as Howard Pain's, do not appear in the French text (whereas French publications are listed in the English version). In some instances it is not clear why certain words have definitions and others do not. For example, both "curvilinear" and "rectilinear" are explained while "gadroons" and "pilasters" are not.

14 Given this, the basic dilemma facing all exhibit co-ordinators rears its head. If you give too much information it may overwhelm, if not enough you lose your audience. If labels are sparse or, heaven forbid, inaccurate in details, you offend and potentially alienate the intelligent visitor and mislead and poorly educate the novice. Confusion results when comparing information carried in gallery labels with exhibit texts as well as Web site spaces, all of which receive different and sometimes conflicting treatments.

15 For example, in certain instances trained design historians might be baffled by this definition of rocaille in the English exhibit text: "Rocaille, Rococo An ornamental style popular during the reign of Louis XV, characterized by shapes inspired by shells." A literal translation of rocaille is simply "rocks," not shells. The French exhibit text, from which the English exhibit text appears in most instances to be derived, defines Rocaille alone (which is not, here, associated with Rococo in the glossary). In reality, rocaille was only ever half of eighteenth-century "Rococo" fashion. Rocaille (rocks) and coquille (shells) form the basis of Rococo designs, that is, scrolls and lines in the form of fantastic rocky grottoes and sea shells, myth and reality mingling in extravagant carvings and detailing. In the motifs section of the French exhibit text is a reference to "coquille-Saint-Jacques," which talks about Saint-Jacques-de-Campostelle as a source for shell designs. The English translation leaves us wondering why we are talking about an eleventh-century Spanish pilgrimage site when defining eighteenth-century French shell motif origins. More to the point, why not discuss the gardens of French Versailles?

16 Terminology is strong in other instances. There is interesting yet brief discussion of meubles meublants (architecturally fixed furniture) and the sensuous linkages to the voluptuous profiles of the bergère and marquise chair forms. However, more time clearly needed to be spent on the glossary in the exhibit text, labels, and particularly in the Web site, as these examples are only a few of many that may either confuse the reader or cause him to crave more of a good thing that, unfortunately, is not there for the taking.

17 Once away from the exhibit it is possible to access a linked Web site created in what appears to have been an afterthought. It may be accessed through the bilingual Musée Virtuel de la Nouvelle-France at http://www.mvnf.muse.digital.ca/expos/meubles. The site is divided into several topics (excerpts, glossary, games, other exhibits, events, comments, and other sites). The excerpt from the exhibit is basically one page that can be printed off only in yellow except for a colourful blue small table (Fig. 4). As previously alluded to, it is linked to a very brief and inadequate glossary. Of little appeal to the furniture buff are references to other non-furniture exhibits. The "events" button is a dead end. Of more interactive educational value are the games, an opportunity to contact the museum by e-mail with thoughts on the exhibit, and links to other sites. The "games" section is basically divided into two multiple-choice topics: can you identify French Canadian furniture by (a) characteristics and (b) style. This short game is limited in the fact that, despite being given four different questions under each topic, the corresponding answer options remain unchanged. This becomes old quickly.

18 This particular exhibit does not lend itself to anything other than an in-house display. This is due to the fact that many of the items in the exhibit are one-off, gracious loans from private collectors, and that both conservators and cabinetmakers, understandably, would not be part of a travelling package. In some instances, it is possible that other museums would not have computer facilities or video equipment available either. Therefore, an opportunity to visit this exhibit at its Hull venue should not be missed for those who wish to see it.

19 Jean-Marc Biais and his team worked long hours to turn this exhibit into a multi-media smorgasbord appealing to a broad spectrum of people hungering for the sight of painted French Canadian furniture. With additional attention to actual content in the various French and English media accompanying future exhibits, along with a more intellectually challenging discussion of the objects themselves, presented within an exhibit having a single, non-conflicting message, the Canadian Museum of Civilization could break new ground, continue to reach new audiences and not just take us but lead us into the twenty-first century. In the future, given the momentum created by Fleming's inquiries, let us hope that Canadian furniture receives the attention it truly deserves from our national museums.

Curatorial Statement

20 Although eighteenth-century French Canadian furniture in original paint has been prized by some collectors for many years, the public at large still believes that these artifacts should be stripped and varnished. This attitude that prevailed in the 1950s and 1960s resulted in the loss or mutilation of much of the exceptional heritage first recorded through the pieces illustrated in Jean Palardy's The Early Furniture of French Canada in 1963. Most of the objects published in that work had been stripped of their original painted, and sometimes decorated, surfaces either through ignorance of the importance of original condition for the study of material history and culture or, through a preference for natural materials as advocated by a variety of designers and restorationists acting without sufficient information and unaware of the negative implications of such treatment for eventual study within an archaeological, historical, or sociological perspective.

21 The exhibit, The Painted Furniture of French Canada 1700-1840, is meant to address the urgent problem of the ongoing destruction of a material heritage that even now can only be partially studied because of the stripping and restoration practices of the past fifty years.

22 This exhibit is not intended to enter into the minutiae of regional differences, doubtful attributions, or other preoccupations of the current literature, but to save the materials without which the former interests can only have a paper and theoretical existence if at all. The exhibit is organized around four basic concepts: action to stop the stripping, renovating and other alterations that these artifacts are still subjected to by the vast majority of dealers and buyers; knowledge, however summary, of the making, finishing, materials and conditions of manufacture, as well as some rudimentary notions of conservation; enjoyment and appreciation of these pieces for their aesthetic qualities growing from a new perceptual understanding of their form and colour; reflection upon the meaning this furniture had for its first owners and the ways in which it may still have meaning for us today. In other words, this exhibit is a rhetorical and didactic work of "haute vulgarisation" that may be received upon several levels, and through secondary themes that replace museological erudition with psychological and functional considerations.

23 The theme of the human body, for example, in its many relationships to these almost invisible objects in the eye of daily life, runs through both the iconography and the text labels. From the "muscle man," through the synoptic image of the turner dressed in his tools and the products of his labour, to the "blasons domestiques" in which pieces of furniture replace parts of the female anatomy as objects of praise, the armchairs, tables, armoires, commodes, boxes, and other items displayed extend human needs and activities into the cultural productions of a time and place specific to our history. The language too reveals this symbiotic relationship through the arms, legs, back and seat of chairs, or the cornice, panel and post of architecturally related pieces that enclose the objects proximate to our most intimate physical space — the body — clothing, bed linens, cutlery, dishes.

24 The two participatory zones of the exhibit — the construction site and the conservator's laboratory — are intended to frame the subject chronologically. The former actualizes a document of the eighteenth century as a joiner demonstrates the techniques of making panels and furniture on site. These are the initial stages in the life of the object, while the conservator's task is to respect the end product of that life and the effects of the passage of time upon its material form within the context of present use. This temporal trajectory coincides with a historical and political evolution reflected elsewhere in hybrid forms and layers of paint that concretize demographic and cultural differences as well as the cycles of fashion related to taste, economic conditions and social change.

25 At the same time, certain motifs and forms persist — the stability and reassuring familiarity of geometric figures, (the diamond and the lozenge), the traditional symbols of belief and allegiance (the chanticleer, the fleur-de-lys), the secular signs of nature, life and common experience (flowers, birds, animals, hearts).

26 In a world more and more dominated by the proliferation of throwaway objects, objects without a past or future, that have no intrinsic value, that no longer carry a psychological freight of emotional or cultural content, we must learn to look again, to appreciate and to understand the lost values of the past, in order to confront, and perhaps to restore some sense, to the empty artifacts of the present.