Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Newfoundland Outport Furniture:

Identifying Irish Regional Links

1 Following a move to Newfoundland from Toronto, Ontario, in 1966, I developed an interest for collecting examples of Newfoundland out-port furniture.1 As this interest grew, it triggered a need to know more about the furniture and effectively set the course of the writer's life.

2 In 1972, I opened an antiques business specializing in the sale of Newfoundland "pine" furniture at Bareneed, Conception Bay, with a friend, Rupert Batten. In 1977, I began working for the Newfoundland Museum in St John's, and in 1983, The Traditional Furniture of Outport Newfoundland (Harry Cuff, St John's) was published. The chief purpose of the book was to increase awareness of the cultural value of Newfoundland outport furniture and to provide a permanent record of typical examples from all over the province.

3 The vast majority of Newfoundland antiques collectors were uninterested in Newfoundland outport furniture at the time and large quantities of it were being trucked to central Canada by mainland antiques pickers. This book was followed in 1984 by The Forgotten Craftsmen (Harry Cuff, St John's). The purpose of this particular book was to provide a brief overview of all levels of furniture-making in Newfoundland, beginning with the arrival in St John's of European cabinetmakers during the late eighteenth century. The furniture-making activities of several factories and furniture shops, a self-taught outport furniture maker, and a handy fisherman were discussed in some detail. Unlike The Traditional Furniture of Outport Newfoundland, this book relied heavily on archival and library research.

4 As curator of Material History at the Newfoundland Museum, I am responsible for developing collections that include a wide range of items of material culture, not just furniture. For this reason, it has not been possible to give the subject of Newfoundland outport furniture a continuous focus of attention. Nevertheless, the exploration of the subject has resumed following one hiatus after another. In more recent years, I have directed attention towards tracing furniture designs to prime sources. The following research report should serve to bring matters up to date and reveal what is currently unfolding in efforts to learn more about Newfoundland outport furniture.

5 The origins of Newfoundland outport furniture, like other Canadian regional furniture, can be traced to designs that the early European settlers introduced. In fact, many late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century examples are virtually indistinguishable from counterparts made in the various regions of the settlers' homelands,2 especially Southwest England and Southeast Ireland, the two areas to which the majority of Newfoundlanders can trace their roots. Such furniture almost certainly was made by British born and trained woodworkers who initially had been brought to Newfoundland by merchants to help build and repair their residences, business premises and fishing vessels and to work at various other aspects of the migratory fishery.3 A relatively small number of these migratory workers settled permanently in Newfoundland.

6 Identifying British regional influences on Newfoundland painted furniture, however, is a daunting task. First of all, outport furniture-makers adapted and copied a variety of models. In fact, any one example of outport furniture can display a whole range of influences and have only a single detail of construction or decoration that might be traced to a British regional source.4 Attempting to spot British regional influences on such furniture is akin to searching for theproverbial needle in a haystack.

7 An even greater obstacle to this work is the relative dearth of published information about British regional furniture.5 Because such furniture was considered to be unimportant, serious study of it has been underway for little more than a dozen years.6 Fortunately, British regional furniture currently is receiving a great deal of scholarly attention from British furniture historians and enthusiasts, and much of the results of this attention is being published either in the yearly journals of the British Regional Furniture Society or in various other publications by individual members of the society.7 Nevertheless, current published inventories of British regional furniture are not yet sufficient to allow matching examples of Newfoundland furniture (or items of North American furniture in general, for that matter) with British regional counterparts.

8 Despite such handicaps, the Newfoundland Museum was able to successfully trace the design of a significant number of pieces of Newfoundland outport furniture to their British regional sources. This work, and the subsequent production of a travelling exhibit based on its results, was achieved only because of the assistance of Dr. Bernard D. Cotton of Lechlade, England, who, along with me, curated it. Routes: Exploring the British Origins of Newfoundland Outport Furniture Design opened at the Newfoundland Museum in St John's in January, 1995.8

9 Up until the time he began working on the exhibit, Dr. Cotton, who is currently Visiting Professor of Furniture, Buckinghamshire College, High Wycombe, had spent at least ten years travelling throughout Britain and Ireland accomplishing a monumental task. He was able to identify and investigate a large number of regional furniture making traditions and compile photographic inventories of regional furniture. It was this work, for the most part, that enabled him to identify examples of Newfoundland outport furniture that could be linked to specific British regions.9

10 Following the successful exhibit project, the focus of collecting and research in the material history curatorial area of the Newfoundland Museum has had to shift from furniture to the fishery.10 Consequently, important co-operative study of furniture design transmission from Britain to Newfoundland, between me and Dr Cotton, has had to be virtually discontinued. Nevertheless, I have managed to keep alive this challenging work, if only on a modest basis. For the most part, this has involved sending photographs of selected items of Newfoundland furniture to British colleagues for confirmation of their suspected British regional origin. So far, the results have been encouraging.

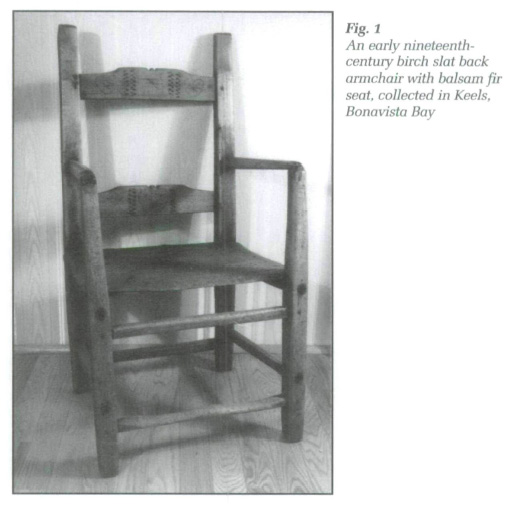

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 There especially has been success tracing design sources to Ireland.11 To date, almost fifty Newfoundland items have had their design or decoration linked to various regions there, especially the Southeast. This is not at all surprising, considering that, by 1836, almost half the total population of Newfoundland comprised people of either Irish birth or descent. More than eighty-five percent of these had come from or could trace their roots to Southeast Ireland.12 Perhaps what is surprising is that, long after migration had ceased, furniture making in outport Newfoundland and the making of country furniture in rural Ireland appear to have followed remarkably similar paths.13

12 The following six items were selected for discussion to provide a sample of the results of current efforts to trace Newfoundland outport furniture design to Irish sources . Most of the Irish-related information has been gleaned from a knowledgeable Irish informant, Mr. Matt McNulty.

13 The early nineteenth-century birch slat back armchair with balsam fir seat (Fig. 1) was collected in Keels, Bonavista Bay. Its shape is Irish, but echoes of it can be found in Scotland and Wales. The badly worn, incised and chip carved decoration on the slats is intriguing. On the crest rail, the decoration includes three incised hearts. The middle heart is flanked by a double band of vertically oriented chip carving. Inside each heart is an incised star motif. On the lower slat, a single incised heart is centred and flanked by a single band of vertically oriented chip carving. Contained within this particular heart are three incised stars.

14 The heart motif was commonly used throughout the Celtic areas of Britain generally, as was chip carving, which often was employed in combination with carved and painted motifs. The incised star motif, however, was used specifically on country furniture made in the southern region of Ireland, especially in the Cork, Limerick and South Tipperary area.

15 In Ireland, this type of chair usually had a seat made from a type of dried grass called sugan. For this reason, such chairs are often referred to as Sugan Chairs. A usual feature of them is that each leg is pierced four times by stretchers. In many examples, two of the piercings are so close together that the leg is weakened at that point, and a fracture results.

Display large image of Figure 2

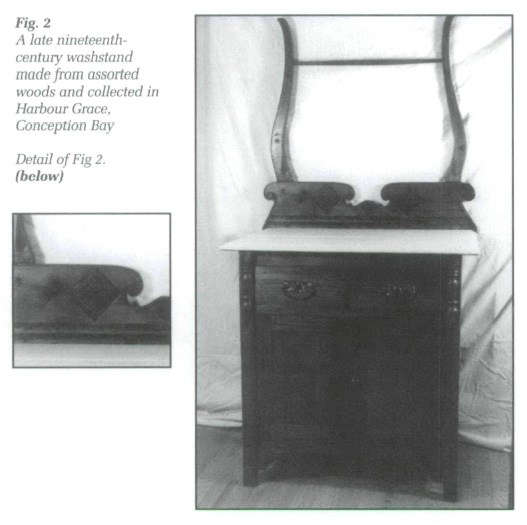

Display large image of Figure 216 It perhaps is not too surprising, considering Newfoundland's cultural roots, to find an early Irish decoration such as an incised star on an early local version of an early Irish country furniture form. But to discover it on an austere, late nineteenth-century North American mass-produced furniture form is entirely another matter. The incised star motif forms part of the decoration on the backboard of a late nineteenth-century Newfoundland outport washstand (Fig. 2), handmade from assorted woods and collected in Harbour Grace, Conception Bay. Also enhancing the backboard are incised bands of hobnail carving. This motif, like the incised star, can also be attributed to southern Ireland. Hobnails were nails having raised heads, two rows of which were put around the rim of the soles of heavy boots. The hobnail motif also is similar to patterns used to decorate cut glass, and Waterford and Cork were early glass-making areas. A motif on the backboard that can be traced very specifically to Southeast Ireland — Waterford, Wexford and Kilkenny — are the diamonds that are filled in with hobnails.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 317 While most of the decorations on the backboard of the washstand can be linked to a specific Irish region, one was used generally throughout Britain. A close look at the backboard will reveal that its edges are carved to resemble twisted rope. This type of decoration was used in the British Isles generally, on good quality mahogany furniture and marble fireplaces. In Ireland, it was used to enhance soft woods and country furniture.

18 Several other details of this washstand are remarkable for having drawn their inspiration from earlier furniture styles or traditions. They include the shape of the backboard [below the harp], the applied split pendants flanking the drawers and the fact that the carcase and backboard were stained to resemble walnut while the top working surface was painted white to simulate marble.

19 Hobnail carving also forms a major part of the decoration on the nineteenth-century balsam fir handmade picture frame (Fig. 3), which was collected in Carbonear, Conception Bay. This item, except for the carving and its alternating bands of red and blue-green paint, is reminiscent of mid-nineteenth-century mahogany veneered examples. Normally, hobnails were limited to panels or corners of objects; they did not cover an entire surface. Such decoration was created using saws, chisels, knives or files. In the case of this frame, the irregularity in both depth of cut and line that clearly can be seen on its surface suggests the use of a sharp knife.

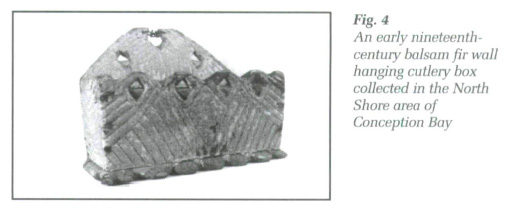

20 The early nineteenth-century balsam fir wall hanging cutlery box (Fig. 4) was collected in the North Shore area of Conception Bay. It is put together with forged nails and retains a number of very old layers of scaling paint. The original finish appears to be yellow ochre, and the surface is carved to suggest wicker, woven saplings, or woven braids of grass. The diamonds are carved and fretted in such a way as to create the illusion that the top edge of the box can be seen through them. It is possible that the wavy detail of the top edge of the box and the base were originally much more pointed, but have been blunted from wear.

21 According to my Irish informant, Mr. McNulty, the wavy detail of the top front edge, the latched or wicker-like carving and its arrangement, and the diamond shapes are Irish influences, which are all slightly exaggerated, but nevertheless can be traced to country furniture in the West and Southwest of Ireland.

22 The chip carved balsam fir wallbox (Fig. 5) collected in Salmon Cove, Conception Bay, and made circa 1840, has residues of its original green paint and subsequent red overpaint. Traces of relatively recent white paint are also visible on the carved areas. The chip carved and incised pattern and style strongly link this item to Southeast Ireland.

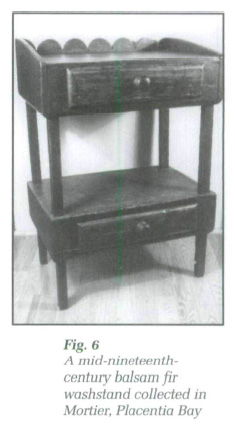

23 The final example is a mid-nineteenth-century balsam fir washstand (Fig. 6), collected in Mortier, Placentia Bay. It was put together with forged nails. End dado joints were used in the drawer construction. It is virtually identical in every respect to examples made in the western coastal area of Ireland.

24 It might be suspected that the examples discussed here were selected because they are the most impressive of the Newfoundland-made, Irish-inspired pieces identified to date. This is not so. The majority of outport examples that recently have been successfully linked to Ireland are no less remarkable and important for their potential to document the Irish roots of Newfoundland culture.

25 The encouraging results yielded by current efforts to trace Newfoundland outport furniture design to Irish sources warrant giving this work significantly increased attention. Planning a travelling exhibit specifically on Newfoundland-Irish furniture would be one way to sharpen the focus and to create a realistic goal. A sufficient number of Newfoundland examples have already been identified to produce such an exhibit, and much of the necessary work has already been done. Though an exhibit would be a temporary product, a permanent record of its information content could be made available in various ways, for instance, in a catalogue, or electronically with a CD-ROM.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 626 What remains to be done to produce an effective exhibit of Newfoundland-Irish furniture, for the most part, involves obtaining appropriate Irish analogues for the Newfoundland examples, whether they be actual pieces, photographs, paintings or illustrations, to display along with their Newfoundland counterparts. An enthusiastic and capable Irish colleague has suggested that a committee for this purpose be formed in Ireland and that he would be most willing to assist.