Articles

"Providential Openings":

The Women Weavers of Nineteenth-Century Queens County, New Brunswick

Abstract

This case study demonstrates how women living in a rural region of New Brunswick depended upon handweaving as a means of supporting or supplementing the household income. The relationship of handwoven textiles to the lives of residents was deeply rooted in the economies of community and household. Upon combined analysis of archival material, census returns, and material evidence, it becomes clear that many more women were weaving for income than previous information would suggest; and contrary to any popular belief, high quality production was not exclusively a male preserve. Working within the context of household, the women weavers bartered their skills for goods or services, floating in and out of the community network as need required.

Résumé

La présente étude de cas décrit comment les femmes qui habitaient une région rurale du Nouveau-Brunswick dépendaient du tissage à bras comme moyen de rehausser le revenu du ménage. Le rôle des produits textiles tissés à la main dans la vie des habitants était lié profondément à la vie économique de la communauté et du ménage.

Une analyse conjuguée des archives, des résultats de recensement et de la culture matérielle indique clairement que le nombre de femmes qui s'adonnaient au tissage comme source de revenu était nettement supérieur à ce que l'on a cru jusqu'à présent. Contrairement à l'opinion populaire, la production de haute qualité n 'était pas le domaine exclusif des hommes. À l'intérieur du contexte domestique, les tisseuses échangeaient leurs talents contre des biens et des services, faisant partie ou non du réseau communautaire selon les besoins.

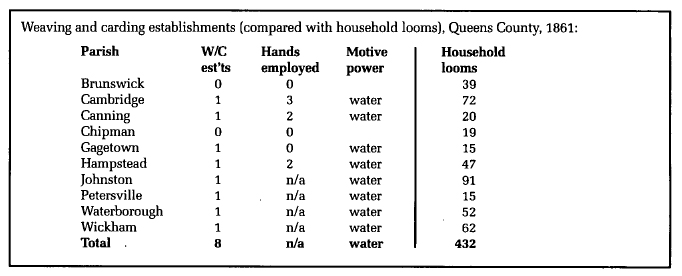

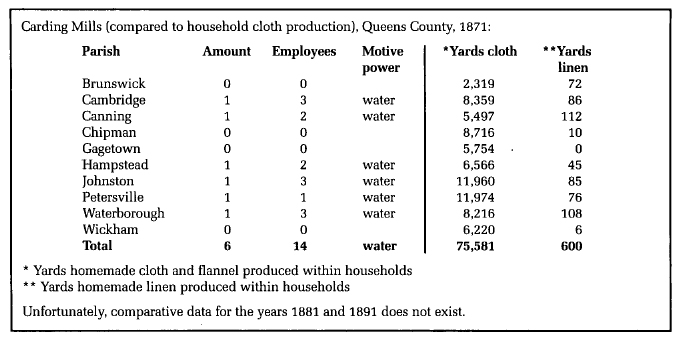

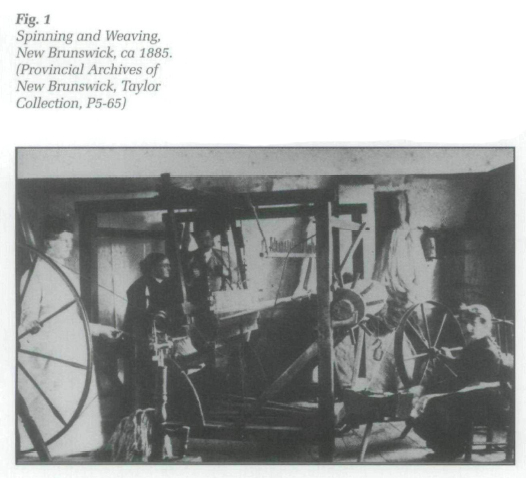

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 11 When Mary Morris Bradley published her memoirs in 1849, she wrote of a time in her life when, newly married to David Morris in 1793, she found herself in difficult financial circumstances. Faced with near bankruptcy over a lumber transaction, able to count on nothing she possessed as her own, and her husband left with "no way to earn anything in the winter,"2 Mary became a weaver. Working out of her home, she received payment for her work in whatever form her customers could provide, and in this way was able to supplement their farm's meager production of milk, butter, potatoes and pork. While her husband's income — from whatever work he could find — was turned over to their creditors, Mary's weaving provided the mainstay for their household.

2 Such a scenario typifies the role of women weavers in the rural economy of mid-nineteenth century Queens County. As a case study analysis, this paper demonstrates the importance of handweaving within the seasonal life cycle of communities and households. Although not exclusively a female occupation, evidence suggests that within the County there were women who depended upon handweaving as a means of supporting or supplementing their family's income. In the majority of these cases their work may not have been recognized as a profession, yet it did constitute an intricate part of the community exchange network.

The Dual Economies of Community and Household

3 Queens County is located in southern New Brunswick, approximately halfway between Fredericton and Saint John. The main waterway is the river St John, which flows centrally through the county, fed by the tributaries of Jemseg, Washademoak, and Canaan Rivers, as well as Grand Lake, and Washademoak Lake. It was along these waterways that settlements of Acadian, Colonial American, and British origin developed beginning as early as the seventeenth century. For both "New World" settlers from Colonial America and "Old World" settlers from France and Britain, textiles were very important factors in daily living. Indeed, they were central to survival and comfort.

4 By the mid nineteenth century, Queens County residents were by no means isolated from the outside world. In 1847 Abraham Gesner described the imports into the province as including "the necessaries and many of the luxuries of refined society."3 He also expressed concern over the impact of the timber trade that continued to "bind the capital and enterprise of the country."4 Many farmers, lured by the promise of cash, abandoned full time farming to work in the woods. As Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Gubbins, a senior British officer serving as the Inspecting Field Officer of New Brunswick Militia had observed in 1811:

Similarly, Abraham Gesner reported in 1847, regarding the growing of flax and hemp:

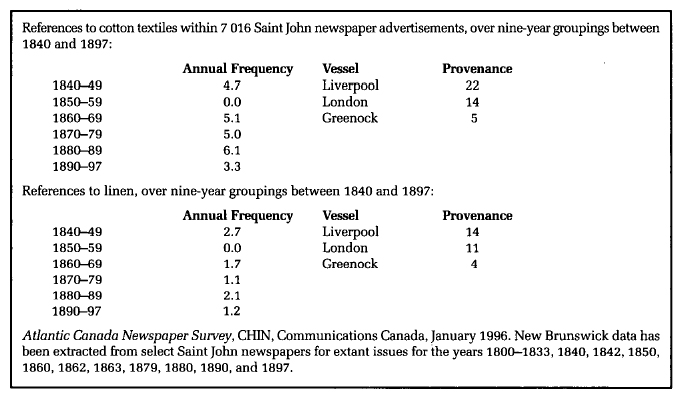

5 Considering the amount of labour and time required to process flax into linen, it is not surprising that cotton imports would be preferred over domestic linen manufacture. Between 1840 and 1897 a variety of cotton and linen goods were advertised as arriving at the port of Saint John on vessels originating (most frequently) from Liverpool, London and Greenock.7 Yet despite the availability of imports, woolen handweaving remained an important production activity within the province. As Alexander Monro reported in 1855:

At provincial agricultural fairs, held triennially in various parts of New Brunswick, the participation of Queens County residents was consistently evident. At the Second Triennial Provincial Exhibition, held in Saint John in 1867, S. L. Peters9 of Queens County was awarded in both the woollen blankets and woollen carpet category (with the notation "Colouring and style of this carpet excellent.")10 That same year, Mrs. Lydia Coy, also of Queens County, received second place in the woollen carpet category (with judges' notation "The spinning and weaving very good, but combination of colors decidedly bad.")11 Three years later, in 1870, S. L. Peters placed second in woollen blankets; and also in 1873, with a first in woollen carpets. In 1873 Mrs Jesse Clark and R. Slipp of Queens County received first in the respective categories of fulled cloth (woollen) and woollen cloth (not fulled).12 Such fairs stimulated excellence and overt competition in textile production.

6 The existence of mills within the county for carding and/or fulling is yet another indicator of the extent to which handweaving activities existed as part of the community enterprise. A carding mill provided the community service of combing washed fleece into quilt batts or yard long strands for spinning. After cloth was woven it needed to be finished or "fulled" (matted and shrunk) to tighten the weave and produce a warmer fabric.13 This could be accomplished at home, although it was a very slow and arduous operation, requiring the assistance of many hands.14 A fulling mill provided a mechanical means of finishing. Depending upon the intended use for the fabric, further processing might involve dyeing, napping (brushing the fibres to raise the nap), shearing (trimming the raised fibres to create an even surface), dressing (applying size to smooth or weight the fabric) and/or pressing.15

7 These processes were sometimes included as part of a fulling mill operation which, in an ideal setting, could consist of a mill, a dye house, a dress house, a press shop and tenter yards. The equipment required for such an operation would include hot and cold presses and weights, pressing (or fullers') papers, furnaces, vats and kettles, napping tools, cloth (or fullers') shears, and tenter hooks or bars.16 Thus a fulling mill required a substantial investment in structures and equipment, and considerable skill and knowledge in the operations. With the exception of one mill in the Parish of Hampstead in 1871, which reported fulling activity as well as carding, the extent to which Queens County mills were involved in fulling, as opposed to carding, is not known.

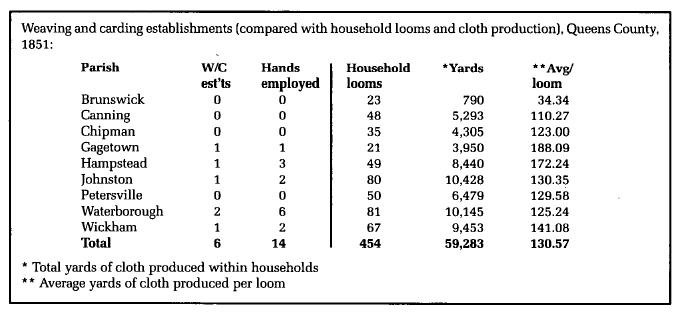

8 By 1851 six "weaving and carding establishments"17 existed in Queens County within a total of nine parishes.18 By 1861 the number had increased to eight (out of ten parishes,)19 and by 1871 there were only six carding mills in existence20 (all water driven). Three of the mills in 1871 employed females, and one was reported to be employing two girls under 16 years of age. The aggregate value of the carded wool ranged in value from $2 000 to $4 180; three were operated in conjunction with a grist mill, another with a fulling mill, and two as simply carding establishments.

9 The household activity of handweaving did not function in isolation — but was rather, on the levels of both production and exchange, an important part of the rural economy. The many stages of cloth production involved (to various extents) the farm family, the miller, the dyer, the spinner, the weaver, the fuller, the merchant, the tailor and the seamstress. Within the family itself the processes of raising and shearing the sheep, dressing the flax, washing, picking, dyeing and spinning involved the entire household.

10 As is evident from the chronicles of Queens County resident Janet MacDonald, the activities of home production were seasonally based, and structured around distinct gender roles. Janet MacDonald's diary demonstrates that women's work included picking, washing, greasing, dyeing, carding, and spinning wool; spinning and twisting flax; as well as quilting and sewing. Men's work involved shearing sheep, dressing flax, and socializing with the women at frolics. Such a division of labour was not uncommon in pre-industrial North American households, with primary production stages being the domain of male labour and intermediary and final stages that of females.21

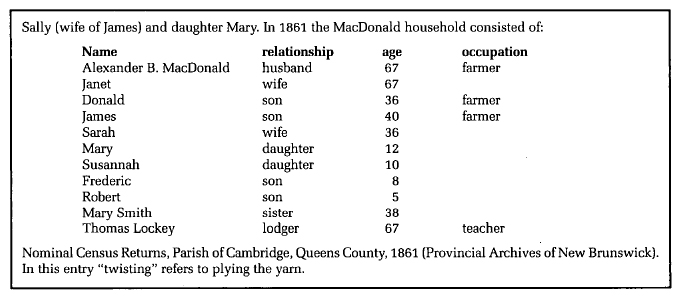

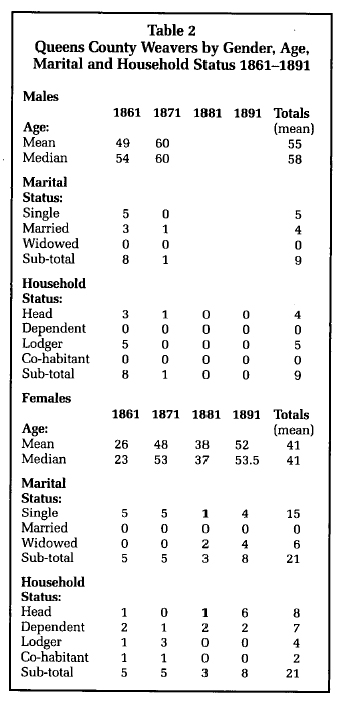

11 The diary of Janet MacDonald, who lived at Central Cambridge (in the Parish of Cambridge), provides excellent insight into the daily life of a Queens County farm woman between the years 1857 and 1868. Her brief entries document the family role of a mother and wife in the advanced stages of her life (aged 62 to 73), and her relationship with the community around her. Born in New Brunswick in 1795, Janet MacDonald was of second generation Loyalist descent.22 She married Alexander B. MacDonald at the age of 23 in 1818, and lived her entire married life on a portion of her family's farm, located at the junction of Washademoak Lake and the St John River, which she inherited.

12 The MacDonald diary describes a very active household economy that interacted with markets far beyond the immediate locale. Services in the form of spinning and sewing were exchanged informally between households, while there also existed a more formal interplay with traveling tradespeople. Of particular interest are the many references to peddlers stopping at the MacDonald farm:23

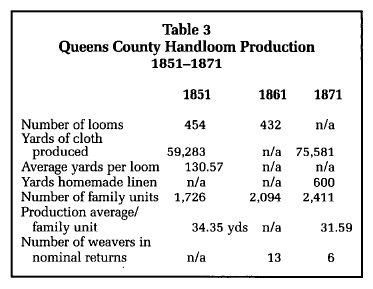

June 28, 1860 — Charlie Brown, the peddler, is here to dinner.

January 15, 1861 — Charlie Brown, the peddler, was here today.

February 20, 1861 — There was a peddler here today with jewellery.

February 21, 1861 — The peddlers, Charlie Brown and Bond, was here today.

February 22,1861 —Mrs. Olmstead is here to dinner, and Cas. the peddler.

13 Although it is not certain to what extent Janet MacDonald may have bartered handwoven goods for the itinerants' wares, her diary does show that visits from traveling salespeople were common and frequent; on February 22, 1861, Janet MacDonald writes, "The peddlers is quite plenty this week [sic]."24 Even the availability of fashionable goods such as jewellery was not outside the realm of county residents:

March 7, 1862 — One man that stayed all night, started this morning, but not without leaving some stock behind him. We had to wash all the bed clothes after him. He served Mr. Bulyea's beds the same.

February 2, 1865 — Mr. Bowser the colporteur was here.

February 9, 1865 — Mr. Bishop the colporteur came today and stayed all night.

14 Throughout the spring and summer months the MacDonald household was busy preparing fleece (shearing, picking, washing, and carding), spinning wool, and dyeing yarn:

June 30, 1857 — We finished spinning today.

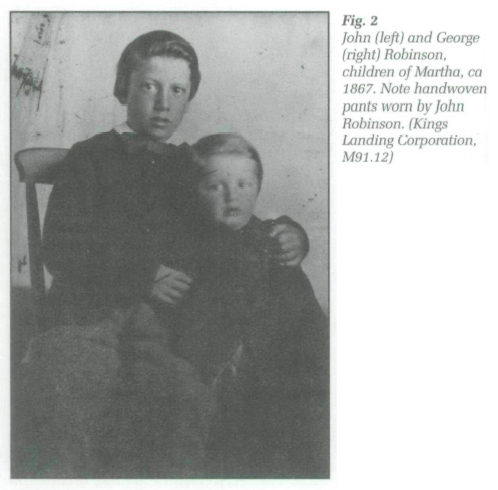

August 11, 1857 — Sally and Mary is twisting25yarn out in the barn.

August 18, 1857 — George and B. was up to Mr. McClarey's with their yarn. We colored black today.26

August 19, 1857 — We are coloring green today.

June 22,1858 — Charlotte Watts came to spin this morning.27

June 24, 1858 — Charlotte Watts and Elinor Furlong is spinning. Mary is braiding splints. Sally is sewing. I have been spinning some today.

July 2, 1858 — This forenoon I was twisting thread and yarn.

May 2, 1861 — We washed wool today.28

May 9, 1862 — Washing black wool today.

April 20, 1863 — Donald shearing sheep. He did not finish, the shears broke. Fred went to Mr. Bulyea's for shears.

April 27, 1863 — We are picking wool.29

April 29,1863 — Greased the wool and fixed it for the machine.30

May 23, 1865 — Commenced to spin today.

15 In addition to wool, Janet MacDonald was also processing flax for thread and twine:

March 11, 1859 — Father is dressing flax these days.31

March 18, 1859 — Sally and I winding twine today.32We finished it.

April 8, 1859 — I am spinning nowadays for a shad [fish] net.

April 23, 1861 — lam spinning flax today.

July 28, 1862 — I was spinning and running out my thread; I caught my foot and fell backwards; I put out my hand to save myself, and fell all my weight and broke my wrist.

And as her grandson, William C. MacDonald later recalled:

16 Janet MacDonald does not refer specifically to weaving at any time, but does mention taking plaid to Joseph Hendry's, sending her son for the pressed cloth, the tailor finishing his work, and making shirts for her son. These activities suggest that she may have been producing cloth. Her interaction with peddlers suggests, as well, a barter link in which hand-woven goods may have been exchanged for other goods. In addition, Janet MacDonald refers to sewing, quilting, frolics and purchasing fabric:

September 27, 1858 — I took my plaid to Joseph Hendry's this evening.

September 30, 1859 — I put my quilting on the frame today.

March 2, 1860 — The tailor finishes this evening.

May 5, 1862 — Ruth is here helping to make Malcolm's shirts. He came home tonight and began to put up his things, he is going away.

December 19, 1866 — Mary has a sewing frolic today. She had Harriett, Emma and Anna Molt, Ruth, Susan and Elizabeth Hendry, Beckah and Adaline McDonald, Melissa Vale and Mary Jane MacDonald. The young men came at night; Douglas and Howard and Joseph Mott, Thomas Vale, Melvin Hendry and James McDonald.

July 7, 1862 — Aunt Charlotte, Ruth, Jane, Susan, and Mrs. William Mott come; they got it off before tea, my double chain. Aunt Betsy helped me piece it.

August 24, 1865 — I put a quilt on today in the old house.

August 17, 1865 — Mary has a frolic today hooking a mat.

January 22, 1868 — I was at the shop, got a pound of calico.

17 Joseph Hendry of Lower Cambridge, to whom Janet MacDonald took her plaid on 27 September 1858, was operating the one (water powered) carding mill in the parish in 1871 arid employed three people. Given the geographies, no doubt MacDonald was also referring to Joseph Hendry's operation in her diary reference to Malcolm going over the lake for the pressed cloth (26 December 1857). This statement suggests the existence of a press shop, which also constituted part of a fulling mill operation.35

Weaving as Women's Work

18 A common assertion among Canadian textile historians has been that handweaving was predominantly a male profession in eastern Canada. This theory has been consistently reinforced by various publications on the topic of textile history in Canada.36 In the landmark 1972 publication Keep Me Warm One Night: Early Handweaving in Eastern Canada, a fundamental distinction was established between domestic and "professional" hand-weaving: once production became part of the domestic duties of women within a household, it was no longer considered to be professional work.37 The concept that handweaving was predominandy a male profession is based upon findings in the 1871 nominal census returns for Ontario in which historians found "some 3,000 weavers" listed, and all but 1 percent were men.38

19 Perhaps the weakness in this conclusion is that the authors do not appear to have closely analyzed returns for the Maritime Provinces. For Nova Scotia alone, it was stated that in the early nineteenth century a "number of men are listed in official records as professional weavers;" however, as was known to have happened in Cape Breton, these male weavers passed their knowledge on to their daughters rather than their sons.39 For this reason, the authors concluded, weaving lost its status as a profession and became part of the regular domestic duties in almost every home. The authors seem to have attributed a lesser value to domestic work within the Maritime economy, and even go so far as to speculate that the gender transition in weaving from men's work to women's work provides an explanation for why "the more complex weaves died out in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick."40 Considering the weaving traditions of New Brunswick, exemplified by the extant material evidence, one can question whether such relatively "complex weaves" ever really died out— but rather instead, the level of complexity remained unchanged.

20 In recent years, Kris In wood and Janine Roelens have closely re-examined the role of women in cloth production by re-defining the term "profession." In so doing, they have discredited the myth that most professional weavers were men.41 Based upon detailed statistical analysis of the 1870 reports of Manufactures for Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Inwood and Roelens argue that as late as 1870, handweaving by women in their homes was an important avenue for cloth production. In fact, domestic home weaving accounted for more than half of all cloth production outside of Ontario in 1870 (58 percent in Quebec, 60 percent in New Brunswick, and 78 percent in Nova Scotia; compared to only 16 percent in Ontario). Clearly these figures indicate that Ontario cannot be considered the norm for eastern Canada. In the words of Inwood and Roelens: "even as late as 1870 domestic production was too important to be ignored in Canada."42 Unlike earlier historians, Inwood and Roelens recognize domestic production as professional work. And in striking contrast to previous conclusions, Inwood and Roelens have found that women dominated handweaving in both Ontario and the Maritimes (New Brunswick and Nova Scotia), comprising respectively 85 percent and 98 percent of the weavers.

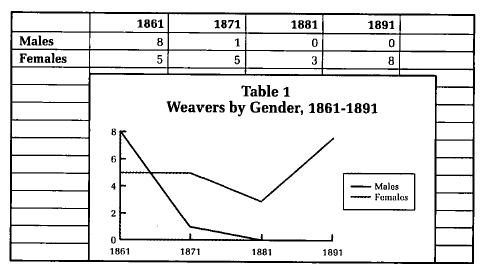

21 In the Queens County census reports for 1861—1891, female weavers significantly outnumbered males by a ratio of 2.3 to 1. Between those years, only 9 of the 30 individuals listed in nominal census returns as weavers were male. Only in 1861 did males slightly outnumber females (8 to 5); by 1881, and thereafter, all weavers were female (Table 1). Of the 9 male weavers, 7 had been born in Ireland, while 18 of the 21 female weavers had been born in New Brunswick. These figures would indicate that even within the limited scope of nominal census returns, most professional weavers in Queens County were New Brunswick born women. Indeed, after 1871, all weavers were female. The differences in gender and birth origins among weavers reflect culturally based distinctions between Irish immigrant and native born populations.43

22 An analysis of the age of weavers listed in Queens County nominal returns suggests that among those with a reported occupation of weaving, there existed a characteristic of maturity. For 1861 and 1871 the mean age for male weavers was 55 years (median 55); while the mean for female weavers between 1861 and 1891 was 41 (median 43). Ages for males ranged from a mean of 49 in 1861 to 60 in 1871, with the youngest being 16 (in 1861) and the eldest 80 (also in 1861); ages for female weavers, all of whom were either single or widowed, ranged from a mean of 26 in 1861 to 52 in 1891, the youngest being 17 (in 1861) and the eldest 79 (in 1891) (Table 2). The mean age range over census returns is significantly wider among females than males; and the mean age variance among single status female weavers suggests a transitional trend from handweaving as a younger woman's occupation in 1861 (mean 26) to a mature woman's (beyond child-bearing years) occupation in 1891 (mean 52).44 This profile is personified in William C. MacDonald's recollection of Betsey Starkey, a weaver his mother had "engaged" to do the family weaving circa 1870:

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 223 When considered within the context of household status and family life cycles, the gender distinctions among Queens County weavers become even more clear. Within the family household, 5 (out of a total of 9) male weavers in 1861 and 1871 were lodgers, while 4 actually functioned as the head of the household. Among females the household status was more varied, in that 8 (out of a total of 21) functioned as the head of the household (main income), while 7 were dependents (providing supplemental income),46 4 were lodgers, and 2 were co-habitants (shared income); none were married (Table 2). This would suggest that all but four of the female weavers were providing sole or supplemental income support for the household. Coincident with the age transition that took place among single females between 1861 and 1891, another transition also occurred from a young, dependent status in 1861, to a mature head of household status in 1891. Of the female heads of household, all but one were widows — the majority of whom had working age dependents living in the household. For these women, handweaving may have provided a supplementary, if not essential, avenue for survival in widowhood.

24 In 1851, in Queens County, approximately 1 in 4 families possessed a handloom (0.26 looms per family). The production average of cloth per family for that year was 34.35 yards (31.4 metres), with production per handloom being 130.57 yards (119.4 metres) (Table 3). This would suggest that in 1851 the 454 handlooms in the county were producing far more cloth than required within the household, and indeed, may have been servicing the needs of the entire county. By 1861 the ratio of handlooms neared 1 to 5 (0.21 looms per family).

25 Cloth production in 1861 was measured by cash value rather than yardage, which makes a comparative analysis difficult; however, returns indicate the average cash value of cloth and other home manufactures per loom was $21.39. The average amount of cloth produced per family in 1871 decreased slightly from 1851 figures to 31.59 yards (28.9 metres). Given that between 1851 and 1871 cloth production (per family) did not change drastically, and also considering that the six weavers listed in the 1871 nominal returns could not possibly have produced the 76,181 total yards (69 660 metres) of cloth reported for the county, it is conceivable that the number of handlooms in Queens County in 1871 would have remained relatively high, in keeping with 1851 and 1861 figures.

26 The total number of handlooms reported in agricultural census returns for 1851 (454) and 1861 (432), compared to the total number of weavers reported in nominal returns for 1861 (13), would suggest that more individuals were handweaving than were listed as weavers in nominal returns (Table 3). Even if the possibility that not all of the households possessing a handloom were active in handweaving is taken into consideration, the vast differences in the ratio of weavers to looms cannot be explained by the existence of itinerants. It is also significant to note the advertisements for cotton warp and homespun cloth, which appeared in Saint John newspapers between 1840 and 1897, confirming that during this time there existed a domestic market for trade in both:

27 Known weavers, such as Mary Bradley (1793), Sybel Grey (1845), Julia Lynch (1849), Lydia Estabrooks (1853), and others, may not have been' recognized by census takers as having an occupation because their handweaving was a secondary or (as in the case of Mary Bradley) temporary source of income. Nevertheless, all received outside reimbursement for their work, and, for all, weaving was a valued skill within the family as well as the community.49 Given this scenario, the widowed females listed in nominal returns as weavers may very well have not taken up a new occupation in widowhood; but rather were continuing on with a skill in which they were already well experienced. Their widowed status may only have made the value of their occupation more apparent to census enumerators.

28 When Mary Morris Bradley of the Gagetown area turned to weaving in 1793, she was in her own modest way providing the sole income for her family:

As Marjorie Griffin Cohen points out, in such a situation household labour — specifically women's work — was critical to family survival:

29 Similarly, Sybel Grey was a Queens County "bluenose"52 woman whose skill as a spinner and weaver contributed greatly to the household, as well as community, economy. In 1845, Mrs Francis Beavan, an English 'gentlewoman' who had lived at Long Creek (Queens County) for seven years, wrote that due to her own inabilities to meet her family's textile needs, and since wool production was an essential aspect of "backwoods life," she employed Sybel Grey to spin and weave for her:

30 After having taken her fleece to the carding mill to be carded, Mrs Beavan left it with Sybel Grey to be spun, dyed, and woven into necessary goods for winter survival. Beavan herself was unable to perform this essential work54 and appears to have been either unable or unwilling to purchase the required goods as imports. Thus, Beavan was dependent upon Sybel Grey, a weaver. Mrs Beavan considered Sybel Grey's work an essential service; and in turn Grey's weaving was a valued source of income to her family. In this case handweaving functioned as a significant element within the community economy. Indeed, considering the winter climate, it is understandable why Mrs Beavan regarded wool production as an important aspect of women's work.

31 Within the network of exchange, Queens County weavers bartered with neighbours and merchants for a range of goods and services. In so doing, these weavers may not have been seeking profits by participating directly in a wage market economy, but instead were simply attempting to better their condition indirectly by securing needed items and services. In the neighbouring county of Sunbury such was the case when Nathaniel Hubbard of Burton was acting as a middleman in cloth manufacture. Handweaving was functioning as a valuable commodity of trade — receiving and exchanging goods for goods:

weaving 17 yards of homespun at 61/2 per yrd

weaving 23 yards of homespun at 6 per yrd

Maugerville, 13th Feby 1833

Oct 1850 - weaving 51 1/2 yds cloth at 15 per yd

Received from Nath'l Hubbard, the sum of two pounds shillings and six pence, being the full sum due...for weaving cloth up to this date 11th January 1849

-Julia Lynch [signed]

July 28/51 Carding 86 lbs wool extra carding

paid to Aug 10th 1851

Charles Hazen & James White

weaving 21 _ yd of cloath [sic]

weaving 13 yd

Received payment

-James Estabrooks [his mark] (April, 1853)

The sum of twenty shillings for weaving, being in full up to this date 3d May 1854

- Jas W Estabrooks [his mark]

Carding 61 lb wool at 2 1/2

Received payment

H Beckwith

Oromocto July 25, 1855

Mrs S Henry Mitchel for Mr Hubbard

- Thomas E. Smith, Wool Carder, and Manufacturer of lumber of every description carding 82 lbs wool55

32 Julia Lynch, Lydia Estabrooks, and Mrs William Estabrook, although obviously weaving for income, are not listed in the 1851 nominal returns as weavers by occupation; James Bailey, however, is hsted. No doubt, given the quantity of looms which were in existence, there were many more women weavers in similar situations for whom archival documentation does not exist.

33 Many examples of handwoven textiles survive today in public and private collections56 as material documentation of the handweaving traditions of Queens County. For many of the women to whom clear attribution can be made, their blankets and coverlets are the only remaining evidence of their work as weavers. If it were not for these artifacts, we would not know that the work had occurred. The Robinson women of Cambridge-Narrows are an example of this: neither Martha Elizabeth (Springer) Robinson, nor any of her four daughters are credited in census returns as weavers, although the material evidence exists to indicate that they were very skilled craftspeople.57

34 In 1847, Martha Elizabeth Springer of Jemseg married John Robinson of Cambridge-Narrows. In anticipation of the marriage, Martha Springer prepared her trousseau of bedding, which included at least two blankets on which she cross-stitched her initials "M. E. S."58 By 1861, Martha and John Robinson were living on the Robinson family farm with John's parents and sister, and seven young children ranging in age from 3 to 11. Martha was not listed in the nominal returns as a weaver, and it cannot be determined as to how actively she was weaving; however, the family reported a cash value of $25 worth of "cloth and other home manufactures" (slightly above the county average of $21.39). Theirs was a wealthy farm of 600 acres (243 ha), with a cash value of $4 000 (compared to the county average of 169 acres (68 ha) valued at $1 331.27). Also reported was one loom, 26 sheep, 10 lbs (4.5 kg) of wool, and 6 lbs (2.5 kg) of scrutched flax — somewhat substantial holdings in comparison to the county average of 9.13 sheep, 27.77 lbs (12.5 kg) of wool, and 0.11 lbs (0.05 kg) of flax.

35 A further indication of Martha Robinson's possible weaving activity (and/or the market for handwoven cloth within the region) is evident in the circa 1867 photograph of her two sons (Fig. 2), in which the eldest wears a pair of handwoven pants. By 1871, Martha Robinson's daughters Mary Ann, Martha Elizabeth, Rachel Jane, and Rebecca Amelia were aged 18, 16, 15, and 11 respectively. Martha Robinson was no longer living, however, in census returns for that year the household reported 20 sheep, 100 yards (91 metres) of homemade cloth and flannel, and 110 pounds (50 kilograms) of wool. These figures are extraordinarily high in comparison to county averages of 7.04 sheep, 31.59 yards (28.9 metres) of cloth and flannel, and 26.48 pounds (12 kilograms) of wool. Given such large amounts of reported cloth and wool, it is highly probable that the Robinson daughters were producing handwoven cloth even though they are not listed in the nominal returns as weavers. Any of the four may have been actively weaving the coverlets and blankets that are now in the Kings Landing Collection.

Display large image of Figure 2

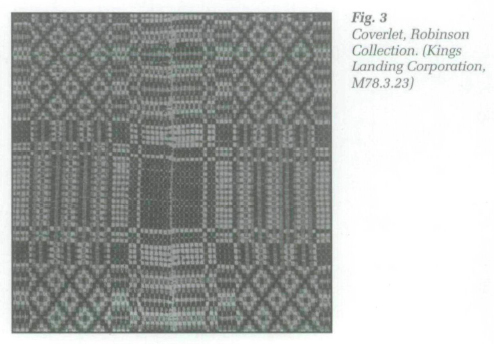

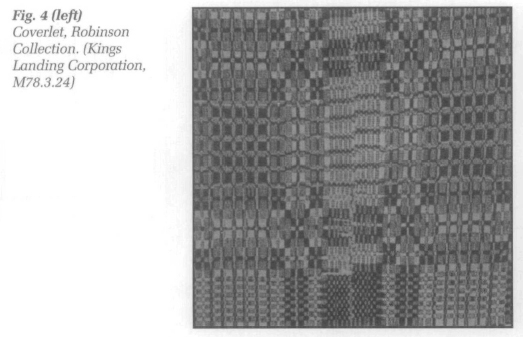

Display large image of Figure 236 It could be argued that the handweaving of the Robinson women does not provide enough substantial proof of an occupational work ethic; the quality of the extant work, however, certainly dispels any doubts about their level of professional skill. An analysis of pattern weft angle, and centre seam variance supports the quality of work produced by the Robinson weavers to be far too precise for that of novices. Handweaving skill and experience can be measured by the accuracy of beating and pattern angles.

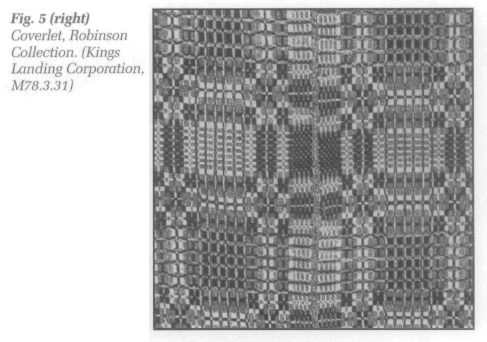

37 The final test of any handweaver's work is at the centre seam — particularly when using an advanced technique such as overshot or double weave, which produces distinct pattern images. Since handloom (as opposed to fly shuttle) weaving requires a centre seam on bedding measuring more than 85 centimetres in width, flaws in beating and weft counts become distinct when the two sides are joined at the centre. For the six Robinson overshot coverlets, all of which represent variations upon a single pattern, the pattern weft variance — that is to say, the widest point at which the patterns of the two sides do not match perfectly — range from 0.5 to 1.4 centimetres (Figs. 3 to 5). The work of skilled and experienced weavers, indeed.

38 It cannot be determined to what extent the Robinson women participated in a network of community exchange as weavers. Yet, the level of skill that is exemplified in the surviving examples of their work, combined with the 1861 and 1871 census reports on home manufacture, certainly suggest more than a self-sufficiency mode of production. Given that all six of the coverlets analyzed represent variations upon one overshot weaving pattern (Monmouth), combined with the level of quality production, it is apparent that these women made a conscious effort to master their craft. The variations in overall pattern designs were obtained by rearranging the tie-up and treddling sequences to produce pattern variations of tables, crosses, and stars (Figs. 3 to 5).59 Such method of weaving is mathematical in nature and cannot be mastered easily or quickly. No doubt the Robinson women valued their weaving skill very highly; for as Francis Beavan observed of Sybel Gray in 1845:

Display large image of Figure 3

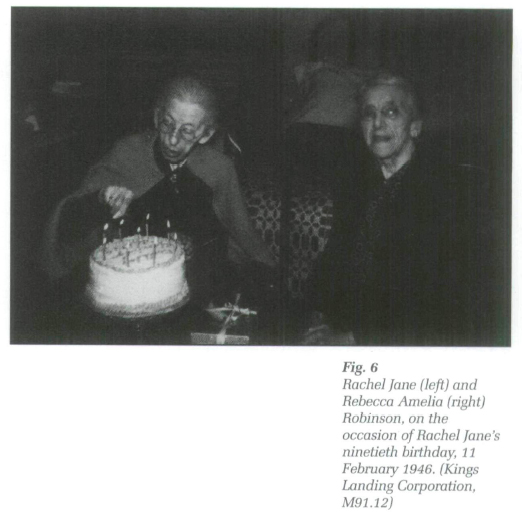

Display large image of Figure 339 Just over 100 years later, on 11 February 1946, Rachel Jane Robinson celebrated her ninetieth birthday, and on the occasion she was photographed with her sister, Rebecca Amelia, cutting her birthday cake (Fig. 6). There, in the background, on Rebecca's bed, is displayed an overshot coverlet, nearly identical in pattern draft to one found in the Robinson Collection — a true testimony to the handweaving traditions of the Robinson family and the personal value placed upon the work of women weavers.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5Conclusion

40 The relationship of handwoven textiles to the daily lives of Queens County residents was deeply rooted in the economies of community and household. As a case study analysis, this research paper demonstrates that county residents did not live in isolation from the outside world, but rather, in contradiction to any pioneer image of self-sufficiency, were clearly part of a larger consumer culture with access to many imported luxuries. Yet, within this context the production of handwoven goods within the home remained important throughout the century. As the operations of each household fluctuated between capital markets and subsistence farming, the women weavers bartered their skills, floating in and out of the community network as need required. In these instances the weavers may not have been seeking profits by participating in the wage market, but instead were attempting to better their family's condition indirectly by exchanging their specialized ability for market goods and services. Within this context, theirs was truly an occupation of 'providential openings,' directed by timely actions.

41 The household activity of cloth manufacture comprised many stages of production that involved the entire community. Services were exchanged informally between households, while there also existed a more formal interplay between households and community commerce. Farmer, miller, dyer, spinner, fuller, merchant, tailor and seamstress all benefited from the enterprise of the household weaver. Within the home itself, the production of cloth was seasonally based and structured around distinct gender roles.

42 The Robinson collection of blankets and coverlets is but one study sample of the many handwoven textiles that survive today as artifactual proof of the weaving skill that existed in mid-nineteenth century Queens County. For women such as Martha Elizabeth Robinson, to whom clear attribution can be made, their blankets and coverlets are the only remaining evidence of their work as weavers.

43 Upon combined analysis of Queens County archival material, census returns, and material evidence belonging to the Robinson family, one fact becomes certain: many more women were weaving as an occupation than previous information would suggest, and contrary to any popular belief, weaving was not exclusively a male occupation (nor was high quality production purely a male preserve). In fact, the majority of known weavers in Queens County were females who depended upon their work as a supplemental or primary source of income. The women weavers of Queens County, New Brunswick, provided a valued service to their community, and, regardless of whether they were officially recognized as working in a professional capacity, contributed substantially to the economic well-being of family and neighbours.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6