Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Making a House a Home:

Company Housing in Cape Breton Island

1 Alistair MacLeod, who sets many of his short stories in Cape Breton Island mining towns, describes the community in "The Return":

When writers or journalists describe mining or industrial towns, the houses of the workers inevitably appear as bleak, blackened abodes where life is eked out in close proximity to the mine. Even though housing for industrial workers is an important part of Atlantic Canada's material landscape, little scholarly attention has been given to these structures. The buildings tell a story about the working people who made this region what it is today, a story sometimes ignored by history books glorifying captains of industry and our military and political leaders.

2 In the late nineteenth century, the Canadian federal government's National Policy encouraged industrialization. The resulting boom in the Atlantic region radically changed the built landscape of many Nova Scotia communities.2 Entire neighborhoods of workers' housing emerged in towns and cities, their housing patterns very different from the region's traditional vernacular styles. Some were built by private individuals and contractors. Most were developed by the coal and steel companies or by the owners of mills, factories and lumberwoods operations. They flourished in towns such as Amherst and Stellarton, Nova Scotia, Wabana and Aguathuna, Newfoundland, and Marysville and Grand Falls, New Brunswick.3

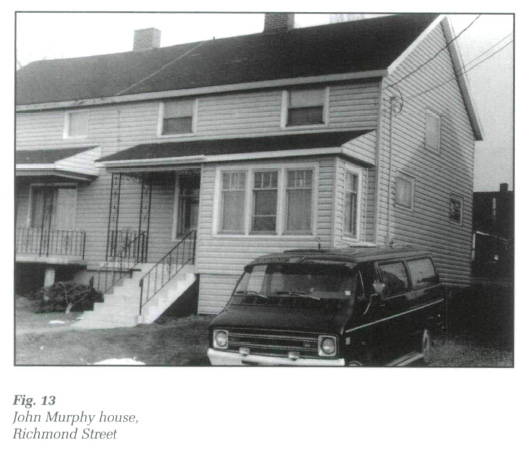

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 Much work needs to be done to record and analyze the company housing of this region. This paper examines only one small part of the process, focussing on the way in which individuals have transformed their prefabricated, company-built houses into "homes." This exploration can give us an understanding of individual and community aesthetics. It helps to explain the way in which people renovate, personalize and transform their living spaces into meaningful places. As architect Alice Gray Read states: "The house is anonymous and mute. Only when it is touched by an owner, lived in and made over inside and out does it begin to bear the identity of its occupants."4

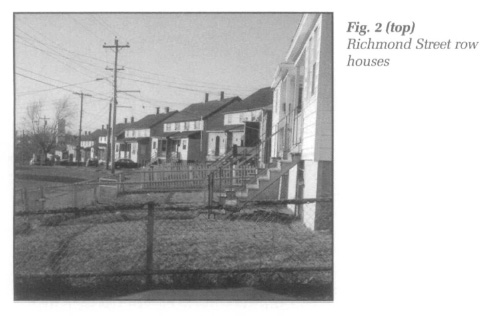

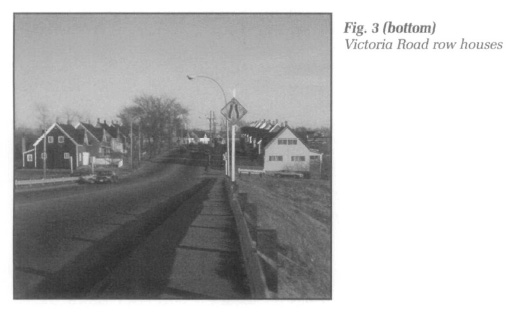

4 In attempting to understand the individual and community aesthetics at work, I have here examined one neighborhood where company-built housing is predominant: the Richmond Street and Victoria Road area of Sydney, within the section of Sydney known as "Ashby"5 (Fig. 1). In this discussion I hope to provide a clearer sense of how this row housing, built on a grid pattern next to the Sydney Steel Mill, has been personalized and transformed over time.

5 With the establishment of the Sydney Steel Plant by DISCO (Dominion Iron and Steel Company) in 1899, and Sydney's concomitant economic boom, construction of workers' housing began in earnest. Sydney's population grew from 3 200 in 1899, to 9 900 in 1901, and 22 000 in 1913.6 Between 1896 and 1900 more than 3 600 immigrants came to Cape Breton seeking work in the coal and steel industry.7 The establishment of the Sydney steelworks followed the vast expansion in the Cape Breton coal industry. Henry Melville Whitney of Boston formed the Dominion Coal Company in 1893 by purchasing several smaller private coal mines that had been in operation since the mid-nineteenth century. In this year he also obtained a 99-year lease of the unworked resources of the coal fields.8

6 This rapid industrialization of Cape Breton Island brought about many changes to Sydney. One author has said that in this transition, the small independent producer was displaced by wage earners: "Sydney had become predominantly a community of wage labourers..."9 Problems facing the city at this period included a lack of housing to meet demand, insufficient water and sewage infrastructure, and abysmal streets and roads. The working class had a difficult life. Low wages, poor working conditions, 13-hour night shifts, 11-hour day shifts (with no pay for overtime) was the lot of the Sydney steelworker of the day.10

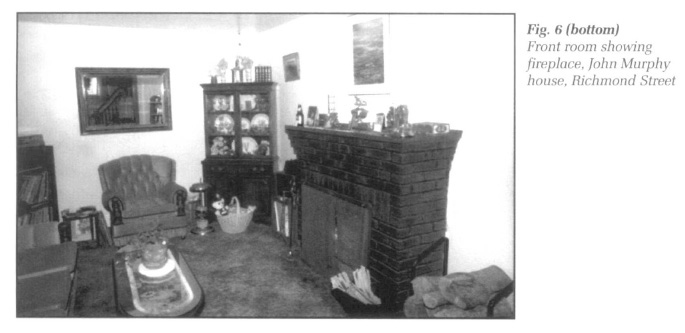

7 In a talk to the Canadian Political Science Association in 1913, Bryce Stewart describes Sydney's company housing. To summarize his study, there were too few houses to meet the needs of the incoming population. In 1909 the Dominion Iron and Steel Company, for example, owned 142 houses; yet there were 303 applications on file with the company for housing.11 Most of these applications were from families; single men made their homes in large boarding houses, in "shacks," or in other working class homes as boarders. Around the steel plant and coke ovens a variety of ethnic groups lived in company-owned housing, including Austrians, Russians, Poles, Italians, West Indians from Barbados, Newfoundlanders and native Cape Bretoners.

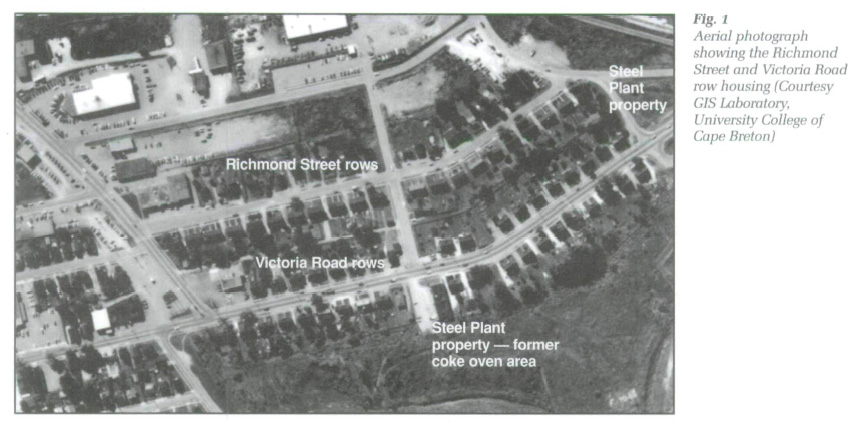

8 In my study area of this one Sydney neighborhood, fifty-five duplexes were constructed between 1903 and 1913, twenty on Richmond Street and thirty-five on Victoria Road (Figs. 2 and 3). The streets of the area are named for the four counties of Cape Breton Island — Inverness, Richmond, Victoria and Cape Breton. The Victoria Road row is located adjacent to the steel plant's coke ovens (dismantled in the recent modernization of the Sydney Steel Plant, but still posing a present-day industrial hazard).12 The Richmond Street rows, likewise, are close to the former bar mill of the steel plant and a short distance from one of the plant's main entry gates.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4Richmond Street Row Houses

9 The plan of the twenty Richmond Street duplexes originally included a front room, 15'9" by 11'3" (4.8 m x 3.4 m), with a coal-burning fireplace, a small dining room, 10' by 12'9" (3 m x 3.9 m), and a kitchen, 12'9" by 12'9" (3.9 m x 3.9 m) to the rear (Fig. 4). The upstairs contained four small bedrooms, two being 11' 4 ½ " by 11'3" (3.5 m x 3.4 m) in size and two being 11' 4 ½ by 9'6" (3.5 m x 2.9 m) in size. A verandah 6' by 20' (1.8 m x 6.1 m) was built at the time the houses were constructed.

10 Each kitchen contained a sink and a trap door leading to the unfinished cellar (Fig. 5). A built-in corner cupboard resembled the ubiquitous British Isles "sideboard," so common in old world communities of Scottish, English and Irish settlers.13 John Mannion points out that large wooden dressers with bottom drawers and shelving on top were the most outstanding feature of Irish peasant furniture at the time of migration to the New World.14 This built-in cupboard with two enclosed lower cupboards and four exposed upper shelves was roughly 4' (1 m) wide and 8' (2.5 m) in height. The lower cupboards were 3' (0.9 m) in height and width; the upper shelves were spaced 15" (38 cm) apart and were 15" (38 cm) wide. Sigurd Erixon points out that this form of kitchen furniture had descended in Europe from the court sideboards of an earlier aristocracy.15

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 611 Each front room had a coal fireplace 19-3/4" (50.2 cm) wide by 26" (66 cm) in height, with an iron fender in front (Fig. 6). It sat on a concrete foundation. A concrete wall laid in a dug-out trench provided the foundation on the front and rear. Present-day concrete end walls were put in by owners of the homes after 1948, when these homes were purchased from the steel company. A concrete pier provides support in the centre of the house. Joists are 2" by 8" (5 cm x 20 cm) in 5' (1.5 m) lengths while upright studs are 2" by 4" (5 cm x 10 cm) in size; a 1" by 6" (2.5 cm x 15 cm) wall plate separates the ground floor wall from the upper storey wall. Rafters (2" by 6" (5 cm x 15 cm) are joined at the peak and are supported by a 2" by 4" (5 cm x 10 cm) the beam. Rough sheathing of 1" (2.5 cm) board covers the entire structure. On the roof there were originally two layers of tar paper covered with wooden shingles but these were replaced by asphalt shingles in the 1940s. The rest of the outer walls have one layer of wall paper followed by 1" sheathing and a layer of wooden shingles.

12 The backyard was fenced in by the owner and contained an outhouse, a coal and coke shed, and a back service lane mat is still evident in the landscape (Fig. 7). A resident recalls one use for this landscape feature:

Ashes from stoves were also deposited in these back alleys for collection every year. Today the alley is used mainly as a walking path for many of the neighborhood's residents, a place to pitch horseshoes in the summer, or a place for various children's games.

13 Many of the men who worked in the heavy mills (including the blooming mill, the bar mill, the nail mill and the plate mill) resided in the Richmond Street houses. While the houses were originally built by the company in 1913, they were purchased by employees from DOSCO (Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation) in the late 1940s for between $1 700 and $1 800. This is a significant time, for it is after this date that a number of transformations in the houses occurred.

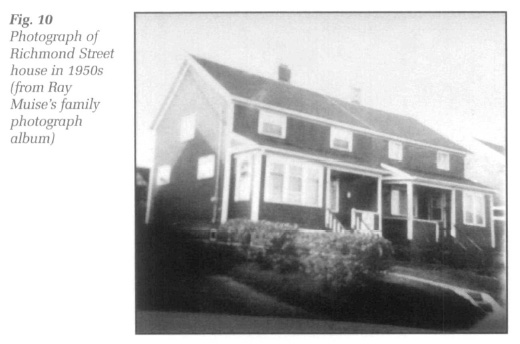

14 When the houses were still owned by the company, a crew of carpenters — company employees — maintained the houses. According to one informant, they were spray painted with oil and oakum twice between 1913 and 1948, giving the houses either a green hue or a dark brown hue. There were no full cellars in these company-built houses; residents began to dig their own basements only after purchasing the homes from the steel company.

15 A coal fireplace originally heated the front room. A cast-iron stove (locally referred to as a "Quebec" heater, after its place of manufacture) warmed the small hallway downstairs.17 For fuel, the hall stove regularly used coke, while the large kitchen stove used coal. In some houses, a small coke heater was also used in the upstairs bedrooms. In the 1940s, hot-air coal furnaces began to appear and by the 1950s a coal stove called a "Warm Morning" became commonly used in these homes.18 These stoves are fondly remembered by residents: when conducting field work I have often heard residents mention how well these stoves worked and how much heat could be generated by this model. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, oil furnaces also began to appear on Richmond Street. One informant remembers that oil furnaces began to appear particularly after the 1947 strike. Many of the cellars were dug out, by hand in most cases, to provide a space to locate the coal and oil-fired furnaces.

16 The interior walls of the houses were originally surfaced with plaster and lath. Today, most are covered with numerous layers of paint and wallpaper. In some, panel board (a popular form of interior walling that began to appear in Cape Breton Island in the late 1960s) has replaced the plaster and lath. Originally the houses had no insulation; at present, most are insulated with fibreglass and are covered by vinyl or aluminum siding, also introduced to the neighborhood in the 1960s.

17 Between the steel plant and the twenty duplexes on Richmond Street is a large field once owned by the company. Here, residents grew gardens or kept cows and horses. As one resident states:

Many steelworking families found it necessary to keep a small kitchen garden, a cow and a few hens to supply fresh produce, milk and eggs. Neighbors shared the product of their toil with each other; whatever produce was not used in a household was given away to nearby residents. The materials used for fencing the gardens were often discarded materials from work sites at the Sydney Steel Plant.

18 The company tolerated the workers fencing off company-owned gardening areas. This squatting on company-owned land for their own use is one way in which original settlers of the row transformed the company-created environment into a meaningful place. Some of the original residents came from rural backgrounds where farming, planting and animal husbandry were common. In this way, older, residual, agricultural patterns continued in the industrial community. This pattern of small-scale gardening and subsistence farming continued into the 1960s when it largely disappeared. Today, more recent houses have been constructed on this side of the street, and the field between the plant and the houses lies unused.

Victoria Road Houses

19 These duplexes are similar in size and shape to the Richmond Street homes (Fig. 8). One difference is the use of a central dormer: this form has a gable roof with the large, central dormer cutting the roofline. This shallow-pitched central dormer hints at the Gothic revival style that began to appear in the Maritimes in the early years of the nineteenth century, becoming extremely popular toward the end of the century. This particular architectural feature was popular in other Cape Breton company towns, including New Waterford, Glace Bay, Reserve Mines, and Inverness.20

20 These houses are 24' by 24' (7.3 m x 7.3 m) in size and possess a front room with a fireplace (called a living room in the original plan), a kitchen and a pantry on the ground floor, plus four small bedrooms on the second floor (Fig. 9). They were built without foundations and, as with their counterparts on Richmond Street, had an outhouse and coal shed to the rear of the dwelling.

21 On both Richmond Street and Victoria Road, original plans did not call for a bathroom or any indoor plumbing. A drain from the kitchen sink led to the backyard; water was obtained from wells in the neighborhood. Plumbing was not installed in many of these houses until the 1930s. One resident states that these houses were drafty and,

Numerous reports about the poor conditions of the company houses in the first thirty years of the twentieth century are verified in a Royal Commission of the time, prompted by labour-management strife occurring in the region.22

22 A sense of some of the activities inside Victoria Road company houses is provided by Mike McCormack in his narrative about growing up in a Victoria Road company house:

There was much interaction between the Richmond Street rows and the Victoria Road rows: people worked together in the mill's departments, they went to the same churches, drank in the nearby Whitney Pier Clubs or local Legion, and played baseball and other games on the streets and nearby fields.

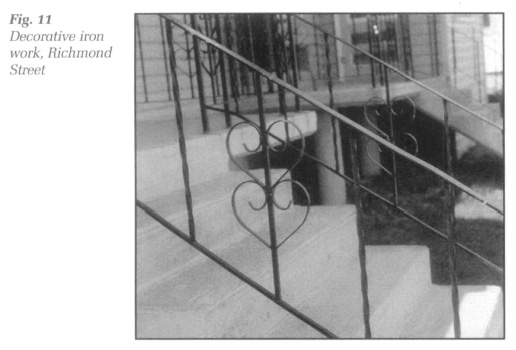

23 The exteriors tell us that people made a number of cosmetic modifications on the company houses only after the houses were purchased from the company in the late 1940s (Fig. 10). Some of the changes made after this date include: enclosing verandahs, painting shingles and trim, siding the homes with aluminum and vinyl, insulating, digging out the basements to install central heating, and reconstructing the end walls of the foundations. The verandahs speak of people communicating with each other. It was a place for resting, doing household chores, relaxing and observing each other's behavior.24 Residents say that much time was spent on the verandahs before the widespread popularity of radio and television. A recent development in the neighborhood is the use of decorative iron work on the verandahs (Fig. 11). A local blacksmith repaired one verandah with iron railings made in his Whitney Pier shop; neighbors borrowed the idea and have begun to copy this decorative technique for their own verandahs.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 1224 While the front yard consists of a metre or so of grass with some shrubs, bushes and trees, the use of the backyard was for a coal and coke storage shed, an outhouse and a garden. As I mentioned earlier, the back alley behind the houses was a service lane, a pathway for children, a place for keeping garbage and ashes and a place for a horseshoe pitch.

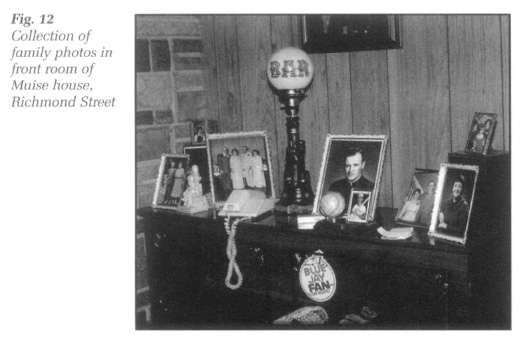

25 While the exteriors of houses and the landscape reveal some of the patterns of the lifestyle of steelworking families, the interiors provide some clues to the way in which people assert their individuality. For example, each house has its collection of family photographs and other mementos in the front room, either on a bureau, on top of the mantle over the fireplace, or on the piano (Fig. 12). In the early years of the twentieth century, pipe organs were also used for this purpose. Ray Muise's photographs reveal significant weddings and portraits of family members alongside autographed baseball cards. Ray is an avid baseball fan who is able to offer many stories about the local Colliery League of Cape Breton, a semi-professional league that operated in the 1930s and 1940s with imported players from the United States. It is the front room, sometimes called "the parlour" of the house, where this form of display is most prevalent. Sometimes used when guests came to visit, it was often employed for other purposes:

Other informants say that the front room sometimes doubled as a bedroom, especially if the household kept boarders, a common practice in the neighborhood in the first half of the twentieth century. While the room functioned as an area of display, it doubled as a storage room and as a bedroom when required. This working-class variation deviates from the standard image of the front room presented in many nineteenth-century pattern books as "the repository for the most elegant and artistic objects" and the most formal room of the house.26

26 While the front room or parlour contains images of the Muise family, the living room's walls include plaques received from friends upon retirement, photographs of horse races and winners, photographs of grandchildren and a crucifix. The small living room is an extensively used room: it is the place where the television is kept and where the large, floor-model radio was once situated. Comfortable chairs and small couches are the furniture of this room. One must walk through the living room from the front entry of the houses before entering the kitchen, making this a heavily traveled thoroughfare in the house. In the bedrooms (the more private areas), the only decorative items of ornamentation besides the paper or paint over the plaster and lath, and the furniture are items such as holy pictures and crucifixes. In a sense, the walls of this house are like a life encyclopedia, offering a visual expression of some of the life experiences and significant events of this family.

27 Some of these interior objects tell us that for many residents of this area, family is important. Many of the significant objects centre around family members, whether children, grandchildren, brothers, sisters or more distant relatives. In addition, various sports activities are also significant: baseball, hockey and darts trophies abound in many homes. Some are placed on display in windows so fellow citizens can view these achievements. Images of rural beauty also abound, particularly images of places such as the Margaree Valley, Cape Breton and the Mira region of Cape Breton. This is an important point, for many steelworking and mining families originally came to the industrial towns from the many rural areas of Cape Breton Island. Many steelworkers have retained a connection to these areas through the building of summer cabins in places such as the Mira and Margaree Rivers of Cape Breton Island. Work is also significant: plaques on walls relate to work situations and events such as retirement. The message inherent in these objects is that while family and sporting events are extremely important, steelworkers also take great pride in their arduous and difficult work.

28 While the walls of houses tell us about many aspects of the daily lives of a steel family, there are other issues about which the objects are silent. Interviews reveal that sharing amongst neighbors was an important feature of this neighborhood. For example, one informant says:

Sharing of gaspereaux and eels — a special food for many — was a way of connecting the community. Indeed sharing in various ways — from helping to build a fence to providing food for neighbors at wakes and funerals — was a common feature of this neighborhood.

29 But all neighbors were not treated with the same respect. Old hurts take a long time to heal and some go back for generations. For example, I asked one informant if there was much rivalry in the neighborhood between the two streets — Victoria Road and Richmond Street. The reply:

Old wounds, particularly ones created during strikes, do take a long time to heal. In this strong union neighborhood, scabs — people who cross picket lines during strikes — are not treated with much respect. The animosity directed at particular families has passed from one generation to another.29

Conclusion

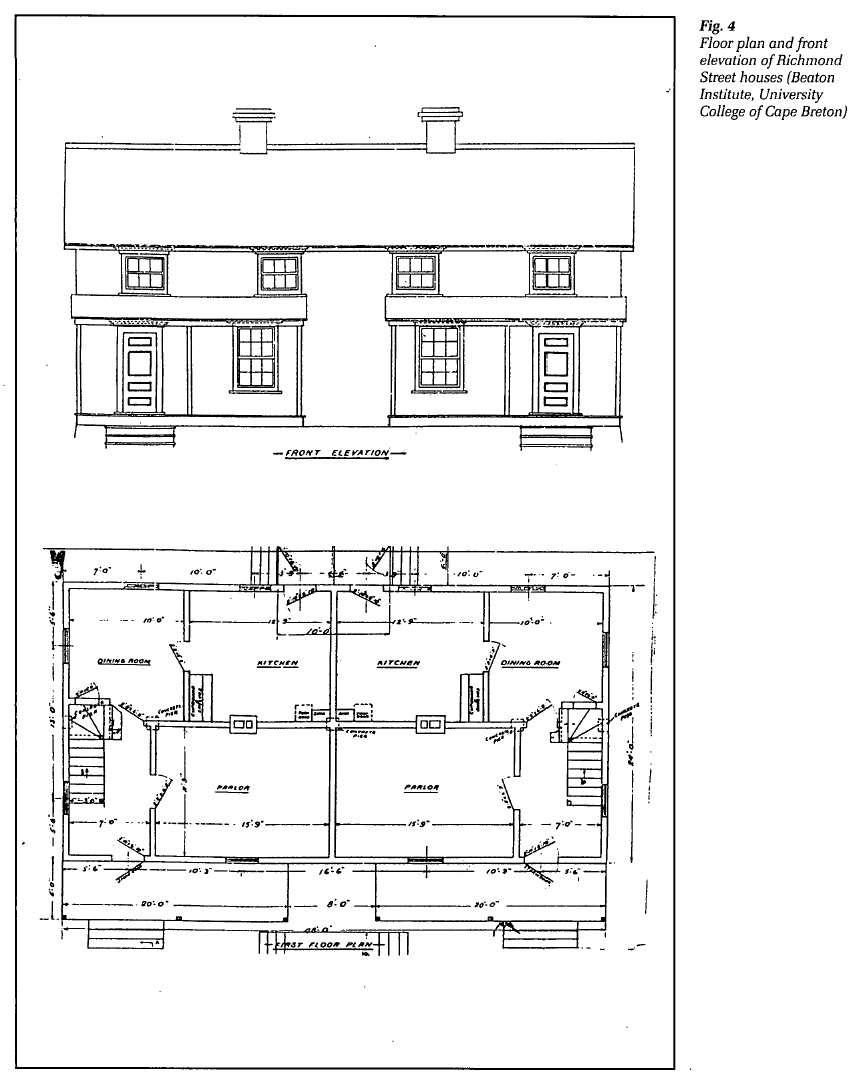

30 These houses and this neighborhood tell us something about how houses are transformed into homes in this industrial community (Fig. 13). One generalization is that it takes much more than a coat of paint to transform these prefabricated spaces into meaningful places or homes where life is lived. Continuing the rural pattern of gardening and animal husbandry was an important feature of the neighborhood in the early years of the twentieth century. Some minor structural changes in the 1940s — constructing foundation end walls and digging out basements, adding insulation, bricking up fireplaces, and adding vinyl and aluminum siding — made these houses more comfortable for the residents. The work was usually done by the owners of the homes, or with the assistance from neighbors, only after the dwellings were purchased from the company. A whole underground economy was at work as well: services were regularly exchanged and reciprocal arrangements were the norm.

31 The way in which houses are furnished and decorated also adds much to the creation of homes. Photographs, plaques, paintings, wall hangings, and wall papers are also ways in which rooms are personalized and individualized, telling much about family history, life's experiences and some of the important moments of a mill family. Oral narratives about past events of significance to the community, such as strikes and strikebreakers, also help to create a neighborhood and sense of belonging in this community.

32 The neighborhood is now undergoing change again. In the past, every neighborhood family worked in the mill. Today, many residents are retired from the plant and others were laid off while the steel plant has been modernized, transforming it from a blast furnace mill to an electric-arc steelmaking process.30 One resident quipped, "When I grew up here they were company houses, now tbey're duplexes; and now I don't live near the steel plant any more, I live in Grecoville," referring to a national pizza chain recently established in the neighborhood. Even though the neighborhood is changing, the buildings, yards and artifacts continue to provide insights into some of the important values that lie at the heart of industrial communities: hard work, competition in sports and pastimes, loyalty to family and neighbors, and sharing of resources and time. By looking at some of the ways houses are transformed into homes in this neighborhood, we begin to see some of the sinew that connects people in our world, as it is shaped by the powerful forces of industrialization.