Articles

When Barbie Dated G.I. Joe:

Analyzing the Toys of the Early Cold War Era

Abstract

The article analyzes toys from the early cold war era as artifacts that reveal the ideology of consumerism and the material culture of gender roles prevalent from the late 1940s until the late 1960s. Toys reflected adult opinions and preoccupations, but also played an important role in communicating these values to the next generation.

Résumé

L'auteure de l'article analyse des jouets remontant aux débuts de la guerre froide, en tant qu'objets révélateurs de l'idéologie de consommation et de la culture matérielle des « rôles sexuels » qui ont prédominé de la fin des années 1940 à la fin des années 1960. Les jouets reflétaient les opinions et préoccupations des adultes, mais ils ont également joué un rôle important dans la communication de ces valeurs à la génération suivante.

1 In 1959 when Vice President Nixon and Premier Khrushchev compared governing systems at the opening of the American National Exhibition in Moscow during the "Kitchen Debate," Nixon focussed his emphasis on our capitalist superiority. He asserted that to Americans, "Diversity, the right to choose, the fact that we have 1 000 builders building 1 000 different houses is the most important thing. We don't have one decision made at the top by one government official."1 He offered an impassioned paean to our freedom of choice between brands and models; in short, he presented the freedoms of exalted consumption.

2 For many Americans, democracy was an abstraction made concrete in the postwar cornucopia of consumer delights; consumption was quotidian democracy. We have inherited a wealth of these objects from the early cold war period (roughly from the late 1940s to the late 1960s).2 They constitute a rich collection of artifacts of the era's history, revealing not only in their symbolic content but also in their astounding volume. Toys, in particular, provide an excellent focus for studying the meaning of consumption. The sudden proliferation of toys in American homes symbolized the success of the consumer society; but even more importantly, the toys themselves taught children that consumption was good, necessary, and fun.3

3 Studying toys also illuminates the ways in which cold war consumption patterns defined differences between people, both on an international level, between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., and domestically, between men and women. Everyday objects literally embodied gender roles; society dictated that men and women each create a very specific relationship to the material world.

4 Cold war era toys take us directly into American homes, where ideology permeated the objects of daily life as well as the daily newspaper. Toys help us uncover what the readers of those newspapers feared and believed, what they took from the articles and editorials and incorporated into their own views of the world. As historian Thomas Schlereth noted, "material culture data provides us with one abundant source for gaining historical insight into the lives of those who left no other records."4 At the very least, toys' purchasers left behind revealing sales records and the evidence manifest in the toys themselves. While toy buyers did not create the mass-produced items they purchased, they carefully selected and gave to their children those toys they thought were most appealing and appropriate. Through studying those choices, we can reconstruct parents' efforts to communicate the important issues of their world to their children.

5 It is important to view toys as artifacts of parents' interests, desires, and anxieties because, in this period of early television, retailers and advertisers had just begun to think about appealing to children as consumers. Adults designed, manufactured, marketed, and purchased toys — not children. Toys reveal what adults wanted to tell children but not what children actually heard. Once a toy had been brought into the home, however, a child might transform the meaning of the toy by the way he or she played with it. The historical meaning of play is a rich area which demands further research, but it is not the focus of this inquiry. In this article, I will explore how toys demonstrated the consumer values and gender roles that were intrinsic elements of early cold war political culture, and how adults conveyed these values to the next generation.

6 The toy industry became big business once the economy revived after World War II. The war had destroyed the foreign competition for domestic toy manufacturers and opened new international markets to the American industry. In 1939, census takers counted 821 workplaces where toys were made; in 1947, they recorded 2 198.5 The baby boom also acted as a powerful stimulus. The industry journal, Playthings, reported in 1956, "The ten-year 'baby boom' [has resulted] in 50 000 000 children who are prospects for toys as gifts."6 By 1950, toy sales reached sixty million dollars, far higher than they had ever been before.7 The industry's production soared from then on; by 1993, American toy manufacturers produced eleven billion dollars worth of goods.8

7 Parents could indulge their children with toys because the growing economy increased standards of living and disposable income across class lines. From 1945 to 1950, consumer spending went up sixty percent,9 inaugurating an era of prosperity and rampant consumption. Much of this eager buying concentrated on products for the home and for family leisure. In 1950, less than ten percent of American homes had a television set. By 1955, the number was up to 64.5 percent of households and in 1960, 86 percent of the homes in the country had at least one television.10 Cars and household appliances also sold in far greater quantities than ever before.

8 Prompted by the family-centred ideology of the period, parents were inclined to pamper their children. Historian Elaine Tyler May found that "it was rare to find anyone complaining about the cost of raising children. Children were not perceived as competing with adults for family resources, but as the opportunity for collective enjoyment."11 Children's possessions also reflected on their parents' ability to buy. Parents could take pride in the quantity of their children's toys as proof of their own affluence and of the country's economic recovery. The abundance of household objects was symbolic of national progress.

9 When Nixon pointed to the growing consumer economy as a sign of American strength and democracy, he echoed the beliefs of many in the nation. The American dream seemed to be encapsulated in a lifestyle, the politics of freedom and democracy embodied in the ability to buy freely and to choose among an array of colours and styles. Such consumption could be prophylactic as well, as expressed in the oft-quoted quip from the period's most famous builder, William Levitt: "No man who owns his own house and lot can be a Communist. He has too much to do."12

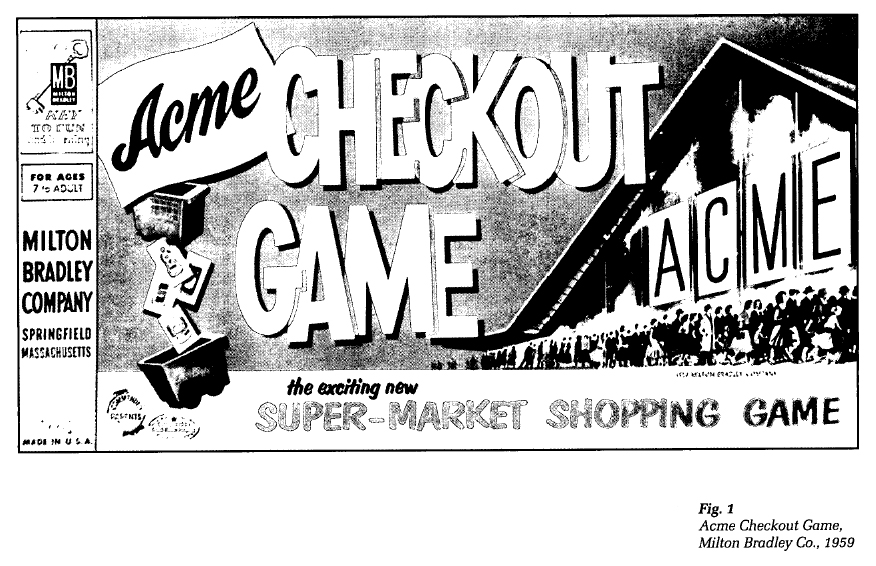

10 Toys contributed to the era's consumer culture. Toy stores flourished, and toys taught the values of the affluent society to the next generation. Nixon would have approved of Milton Bradley's "Acme Checkout Game," which came with markers in the shape of supermarket carts. Players moved over the game board by making their way through the aisles of merchandise, advancing with shoppers' special cards and losing turns in long checkout lines. The aisles on the game board were illustrated with real brand-name products like "Maypo" cereal and "Band-aid" bandages.

11 Parents could also buy child-sized shopping carts, so children could re-enact the experience of shopping without the interference of following the board game's rules. The carts could be filled with exact (although empty) replicas of S.O.S. scouring pads, Kellogg's Corn Flakes boxes, and Campbell's soup cans, among others, all made by the original companies. The "goods" were always carefully labelled with brand names; there were no generic cans of peas or boxes of anonymous detergent. Playing "shopping" thus reinforced advertisers' messages that brand names mattered, that seemingly similar products could be distinctly different, and that the discerning shopper could choose wisely among them to find "the best."

12 Much of this grocery shopping, both real and pretend, was going on in the new suburbs constructed across the country. Suburbia symbolized two of the keystones of cold war domestic ideology — the consumption ethic and the glorification of the nuclear family. Suburban homes were new, and builders designed them for family life. Postwar families preferred suburban settings to older urban or rural communities, and government policies encouraged suburban growth.

13 The acute housing shortage after World War II was exacerbated by the flurry of marriages and the baby boom. Instead of concentrating on improving the urban housing stock, the mortgage and lending policies of the Federal Housing Administration encouraged the funding of new, single-family houses, which also suited the tastes of the young families waiting to fill them.13 A poll conducted by the Saturday Evening Post in 1945 found that only fourteen percent of its respondents wanted to live in an apartment or a "used house."14 Between 1947 and 1951, the company of Levitt and Sons turned a former potato field on Long Island into a community of 17 450 houses and 75 000 people.15 While the Levitts were probably the most famous builders of the period, they were by no means unique in their efforts.

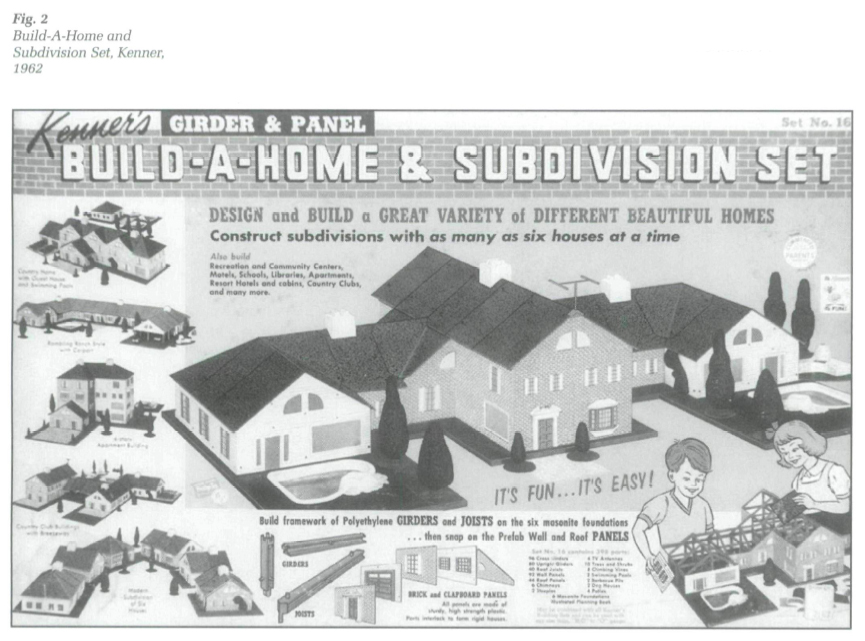

14 Suburban life required the family car. The construction of new communities was not matched with expanded systems of public transportation; instead, the state and federal highway systems expanded to connect suburbs and their neighbouring cities. Cars, a necessity of suburban life, were also an important symbol of the family's status and buying power. American car manufacturers created new models annually, attracting huge attention with each year's unveiling, although few featured important engineering differences. While nothing much changed under the hood, the new designs made it obvious who was making-do with outdated models. Toy cars faithfully followed suit, offering young boys as many choices as their fathers.

15 The "family room," which became an increasingly common feature in suburban homes, crystallized the cold war familial ideal. The term, first coined in 1946,16 referred to a space reserved for informal family interaction — the site for family "togetherness." Togetherness needed a room of its own because it often involved the bulky paraphernalia of play: cold war togetherness required activity and activity generally required the purchase of various games and equipment. Unlike the family life of the nineteenth century, which incorporated children into their parents' pursuits, mid-twentieth-century family life began to centre around children's activities, or special activities considered appropriate for their inclusion. The family room of the 1950s signalled the primacy of children and their play as the focus of the family's time spent with one another.17

16 While psychologists, social critics, and popular literature encouraged fathers to be involved in family life, women spent the most time as full-time parents. This was as it should be, according to cold war ideology: female domesticity was a bulwark against communism.18 Cold war polemics characterized communism as a cancer that transcended politics and also attacked the social fabric of a nation. As witnessed in the Soviet Union, communism drove women out of the home and put them to work, forcing children into state-run daycare centers. To American values, this constituted an assault on the social unit basic to democratic society — the family. In response, postwar American society reasserted the importance of the "traditional" family structure with a male wage-earner and a female housewife and mother. This logic placed the domestic woman at the centre of American values and viewed her domesticity as a weapon against any subversive communist influences.

17 The ideal and reality ran counter to one another, but cold war society did not publicly recognize the contradiction. In 1950, 23.8 percent of married women had paid jobs outside the home; the figure climbed steadily to 30.5 percent by 1960 and 39.6 percent by 1969.19 Many women of the period embraced the domestic ideal and saw work as a diversion to pass the time until marriage, or as a necessary evil rather than a joy. Two women who came of age in the 1950s remembered: "Education, work, whatever you did before marriage, was only a prelude to your real life, which was marriage." "Marriage was going to be the beginning of my real life."20

18 An article in Life magazine in 1953 explained away women's wage labour as undertaken solely for the good of the family: "Unlike the strident suffragettes who once were eager to prove their equality with men, the typical working wife of 1953 works for the double paycheck that makes it possible to buy a TV set, a car — or in many cases simply to make ends meet."21 She worked not for job satisfaction, but to increase her buying power as a consumer, for herself and particularly for her family.

19 Girls' toys mimicked their mothers' assigned gender roles, as mothers, homemakers, and consumers. The ideology of gender stereotypes was a prescribed set of ideas that took on life and force as it shaped behavior. These ideas forcibly marked the common activity of everyday life, where, at least in the ideal, men and women each had their own sphere of power and responsibility. Women cared for their homes and the nutritional and emotional needs of their families. They mothered, nursed, cooked, cleaned, decorated, and shopped, surrounded by the tools of their various callings. In the postwar toy boom, manufacturers sold toys and games that let girls perform, in miniature, the full range of "appropriate" female behavior.

20 The fashion in doll houses mirrored the latest architectural trends. Kenner offered the "Girder and Panel Build-a-Home and Subdivision Set" that could produce new neighbourhoods with schools, motels, libraries, and community centres, just like the new suburban towns. A Louis Marx & Company doll ranch house came with its own modern appliances and bathroom fixtures, and even included a baby in a high chair for the kitchen. The moveable plastic furniture let little girls experiment with home decoration. Grown women played in a similar way with Con Edison's "Plan Your Kitchen Kit" made for housewives who were building, renovating, or dreaming about new kitchens. The sets helped women and girls visualize new kitchens, and encouraged the idea that the latest was the best and most desirable.

21 Women's housekeeping tasks could be faithfully reproduced by their daughters who played with their own child-sized carpet-sweepers, vacuums, and pots and pans. Some of these were made by the same companies who manufactured the working models. Bissell Carpet Sweeper Company sold versions for real use and also the "Little Queen Carpet Sweeper" for girls. Companies who did so could start inculcating brand-name loyalty at an early age.

22 The Kenner "Easy-Bake" and Deluxe Topper Corporation's "Suzy Homemaker" toy ovens were among the most popular and most beloved of these toys. Using a light bulb as a heat source, either oven could bake real but diminutive cakes. Aspiring young cooks generally had to rely on the packaged cake mixes sold specifically for this use, since it would have taken immense patience to adapt regular recipes to fit the tiny pans and to cook properly under light-bulb power. The Easy-Bake slogan promised that little girls could make "Food as Good as Mom's," using the Betty Crocker mixes marketed with it.

23 The little girls at whom the advertising was aimed learned several things: that little girls grew up to be moms and that mom's job was to be a homemaker as well as a mother; that moms, not dads, were in charge of baking; and that cakes were baked from mixes. Looking at the way the products were both advertised and used, we can see that lessons in gender roles were seamlessly linked to lessons in the burgeoning consumer economy. In the early 1950s, Americans began to spend a larger proportion of their disposable income on food; this increase was not due to a rise in basic food prices but to the marketing of new kinds of convenience foods.22 Toys reinforced the message of the crowded supermarket aisles that most food could be found packaged and processed and that cooking was a matter of assembling the appropriate cans and mixes. In 1953, food writer Poppy Cannon wrote an article that included an ode to the can opener, "That open sesame to wealth and freedom...Freedom from tedium, space, work, and your own inexperience."23

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

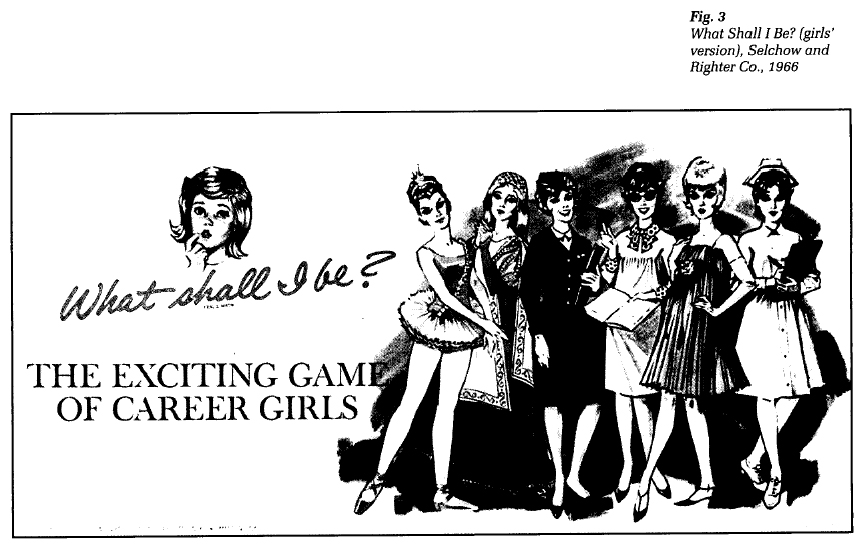

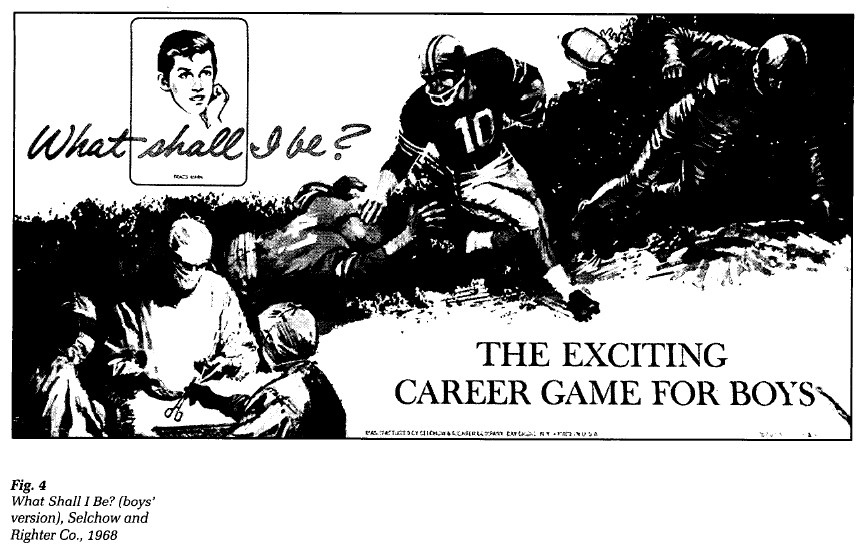

Display large image of Figure 424 Some of the era's board games allowed for the possibility of women's work outside the home, but only within a very narrow spectrum of opportunities. Selchow and Righter Company made the "What Shall I Be?" game in two versions, one for girls and one for boys, with no overlap between the careers offered to each. Girls' choices in the 1966 version included the "helping" professions, like teacher or nurse, with some glamorous options like stewardess, ballerina, actress, and model. Boys playing with the 1968 edition could try out becoming doctors, engineers, astronauts, scientists, athletes, and statesmen. None of the girls' jobs offered represented the majority of real women's wage labour, which was concentrated in the "pink collar ghetto" of secretaries, clerks, and waitresses.

25 An article in Parents' Magazine exploring the role of fathers proposed that fathers could help children "choose a vocation" by taking them to see the world of work. "A daughter can be brought into contact with a social worker, librarian, nurse, secretary, dietician, teacher and beautician. A son can learn what a doctor does, how a lawyer puts in his time, the way a salesman functions, why an engineer enjoys his work and ways in which an expert mechanic busies himself."24 Experts, toy makers, and even many women themselves agreed on which were the properly feminized occupations.

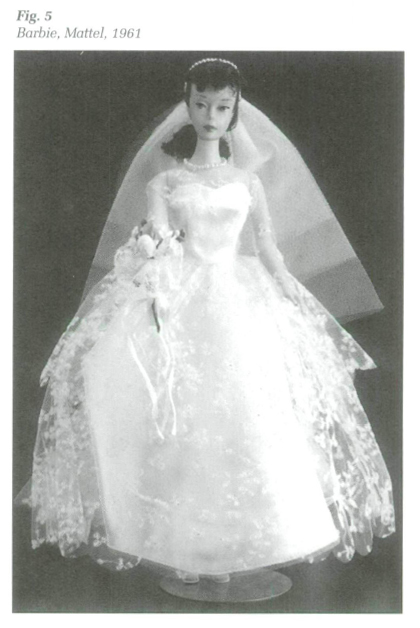

26 The undisputed classic girls' toy of the cold war era was the "Barbie" doll, introduced by Mattel in 1959. Barbie was a textbook of lessons on proper behavior. These lessons taught prepubescent girls about how to behave both as young women and as young shoppers. Mattel targeted pre-teen and young teen-age girls as Barbie's market. She was sold specifically as a fashion doll. The ads promised: "Girls of all ages will thrill to the fascination of her miniature wardrobe of fine-fabric fashions....Feminine magic! A veritable fashion show, and every girl can be the star!"25 Barbie on her own cost a relatively modest three dollars when she first came out, but her clothes and accessories earned Mattel healthy profits.

27 Barbie illustrated fashions in bodies as well as apparel. Her improbably big-busted, slim-hipped, long-legged figure was the fifties ideal, more easily realized in a doll than in far less malleable human flesh. Like her imperfect real-life counterparts, however, even Barbie wore restrictive undergarments. Mattel sold an embroidered girdle with a matching strapless bra, a half-slip, and "panties" for a dollar under the name of "Fashion Undergarments." Barbie's bras and girdles were not all that far off in the future for her young owners. In 1950, according to historian Marjorie Rosen, "eighty-five percent of women over fifteen wore bras, girdles, or both....Corsets had become a $500 000 000 annual business."26 Although Barbie's generous bustline was an unlikely attainment for most women, that was no reason for despair as the padded bra had long since made its debut. Even Barbie's feet were a cultural artifact: she had permanently shortened Achilles tendons, as would many real women who, like Barbie, spent too much time in high heels. When Barbie's outfit required flat shoes (a rare occurrence), then the shoes were built up inside to accommodate her fashionable deformity.

28 Barbie's owners identified with her.27 One woman who donated her vintage Barbie to the Strong Museum, in Rochester, New York, complete with several outfits and all their accessories, told the curator about her own experiences with the doll. She had requested the brunette Barbie as a gift, since she had brown hair and wanted the doll to look as much as possible like her. She was so serious about her wardrobe collecting that in 1961, when she was in fourth grade, she laboriously typed up the current catalogue of available clothes so that she could circulate the list to friends and relatives for future presents (she would mark off the outfits as she got them to avoid duplicates).28 Young women played with their Barbies, dressing and redressing them, imagining scenarios to fit the clothes, imagining their lives would develop like Barbie's.

29 While Barbie's clothes painted the picture of a rather glamorous life, a life of endless school vacations, her designers meant her to glorify reality, but not forsake it entirely. Barbie's creators, Ruth and Elliott Handler, named her after their seventeen-year-old daughter and imagined Barbie to be roughly their daughter's age as well. One of Barbie's more expensive, and most elaborate, outfits was her wedding dress. As it was described in the brochure listing Barbie's clothes in 1961, the dress was a "magnificent church wedding gown with formal train; fashion for a fairy princess." The set even included a "sentimental blue garter, bridal bouquet, and white slippers." The median age of marriage for women throughout the 1950s and 1960s was roughly 20;29 therefore, it was quite reasonable for a teen-age girl to be thinking about her own wedding in the not very distant future as she still played with her Barbie doll. Barbie's wedding gown both stimulated girls to fantasize about their own moment as brides, and helped shape the expectation that they should marry soon.

30 Mattel provided Barbie with everything, even her own made-to-measure mate, Ken. Ken had a rare role in a male-dominated society: he existed only as an accessory for Barbie, having little life of his own other than to escort her and to stand stiffly by her side. Barbie's owners could purchase friends for her as well, including the first African-American doll in the Barbie line, "Francie." Introduced by Mattel in 1967, the "Colored Francie" was simply a white Francie doll with darker skin colour. The Francie doll did not sell well to the unimpressed African-American community and Mattel quickly took her off the market. Mattel tried again in 1968 with Christie, a doll with explicitly African features along with her dark skin. Christie proved successful enough to stay in production. Other dolls of colour joined her in the next few years.30

31 Barbie always had the right smile and the right outfit. While that might have been enough to guarantee her plastic popularity, other toys taught the subtle and elaborate rules of real-life dating, particularly Transogram's "Miss Popularity" board game, Hasbro's "Dating Game," and Milton Bradley's "Mystery Date." Mystery Date bluntly ranked potential suitors as "duds" or "dream" dates, associating the dream date with the proper white, middle-class clothes and haircut.

32 Boys' toys were as didactic about gender roles as girls' toys. An article in a 1950 issue of Better Homes and Gardens asked in its tide, "Are We Staking Our Future on a Crop of Sissies?" The author, Andre Fontaine, told fathers that they had to encourage their boys to seek adventures. An English anthropologist noticed during a trip through America that the worry that one's son was becoming a "sissie" was "the overriding fear of every American parent."31 Just as Barbie dolls specifically taught girls about being attractive women and acting within the confines of the home, many boys' toys offered instruction in the manly arts of physical conflict and fostered skills necessary to master the world outside the home and family. While girls had fashion accessories and Easy-Bake Ovens, boys needed guns and rocket ships.

33 Boys who imagined themselves to be cowboys, astronauts, and soldiers played games of conquest. Each of these roles often centred on defeating a particular enemy, whether human or alien (or humans with alien ideologies). They also involved taming the wilderness: cowboys extended the frontier out across the plains and deserts, vanquishing wild Indians; spacemen explored the vast cosmic reaches, making the galaxy safe for human travel and perhaps colonization; G.I. Joe and his companions made the world safe for democracy — defeating nasty fascists and communists whose imperial plans rivalled our own.

34 These sorts of games were far more explicitly topical and political than what cold war society considered proper play for girls. Girls were to concentrate on the "female" tasks of making themselves attractive, learning to be good mothers, and keeping the home fires burning and the hearth clean. Because they would one day be men, and therefore in charge of the running of the world, boys' games took far more interest in contemporary events. Young astronauts could keep track of the real astronauts' progress and imitate it in their own voyages, just as prepubescent warriors could pay careful attention to the latest fashions in nuclear subs, fighter airplanes, and other military hardware.

35 The hottest fashion in guns in the 1950s and early 1960s was for whatever the well-equipped cowboys might have drawn, a close reflection of the western boom on television. At the forty-seventh annual Toy Fair in 1950, cowboy holsters and pistol belts were "the fastest-growing branch of the toy business." Stanley Breslow, president of Carnell Manufacturing Company, stated in amazement, "Last year, there were enough holster sets manufactured to supply every male child in the United States three times over."32

36 Postwar Americans of all ages were intrigued by the legend of the West. Life magazine ran a seven-part series celebrating the "Old West" in 1959. The Old West lived on in the cold war years, re-enacted nightly on the television set. Westerns were among the most popular shows, the longest running series, and created many larger-than-life cowboy stars. In 1959, westerns constituted one-fifth of the network programming, monopolizing twenty-five percent of total viewing time.33 The Wild West could be incorporated into daily life by purchasing one of the lamps, blankets, lunch boxes, or other items that were decorated with western images.

37 The cowboy myth centred around the lone heroic individual, never quite part of the community, even if he had seemed to settle down. The cowboy never traded adventure for comfort and security. He lived at the very edge of Anglo civilization, an edge where life-and-death struggles with nature and Indians were part of the scenery. It would be hard to imagine a life further from the realities of comfortable, suburban culture, home to most of these twentieth-century would-be cowboys. Toy manufacturer Stanley Breslow noted that the biggest markets for cowboy toys were in and around coastal urban areas and that "only twenty per cent of our business is in states that have real cowboys."34

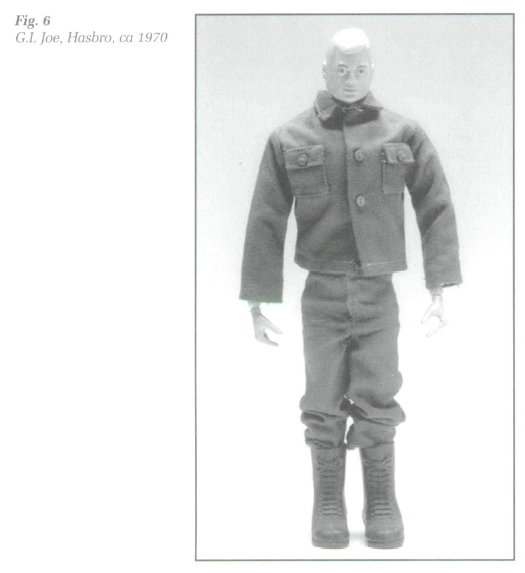

38 It is interesting to note the direct contrast between the surroundings evoked by girls' toys (dress-up clothes, miniature stoves and home furnishings, doll houses) and these toys for boys. Society considered toys that re-created the home and the established social order appropriate for girls, and toys that imagined a more anarchic and individualistic culture correct for boys. Little girls learned the virtues of orderliness from housecleaning toys and stability from elaborate ranch houses and bulging wardrobes. Little boys grew up on stories of men who rambled like the tumble weeds, living the slogan, "Have gun will travel." They could arm themselves with the "Stallion 45 Mark n" gun and holster set, the "New Smoking Texan, Jr" cap pistol, the "Rifleman" rifle, the "Fanner 50" cap pistol, or any one of hundreds of other choices.

39 Playing cowboy offered an escape from all the more confining elements of life that hemmed in energetic boys. Parents' rules were replaced by the simple rules of frontier life, where only the laws of Nature reigned. The disciplined child who was a well-behaved member of his school class, his boy-scout troop, his little league team, could become a free agent, the quintessential individualist. His real life had been tamed of all adventure, removed from all the dangers his parents could eliminate; his imagination gave him wild challenges to conquer, elemental forces to live through or twist to his will. The neatly trimmed suburban landscape gave way to sage-brush swirling in the wind. While social commentators in the 1950s and early 1960s criticized the overwhelming forces of conformity, the "cowboy" lived his own life, by his own rules. Sheriff or outlaw, he ignored the niceties of civilized society.

40 Despite their seeming lawlessness, these games had subtle rules of their own. There were always good guys and bad guys, and you could tell the difference between them. In cowboy and Indian play sets, the cowboys and Indians were made in clearly different colours from one another, dressed and armed differently as well. The games were fun only if the two sides were fairly evenly matched; otherwise the game would end too quickly, without the labyrinthine plot twists and turns that were necessary for a full afternoon's play. Such games were not unlike cold war politics: cowboys and Indians could be read as Americans and Soviets who, despite their frantic efforts to win the arms and space races, seemed to compete on a fairly level playing field, each team winning the advantage only marginally and briefly.

41 At the same time as they offered an escape from the safety and social conformity of the period, cowboy and Indian games also reinforced the prevailing political ideology. This was well before the concept of multi-cultural tolerance had made strong inroads into American society. Often, the only good Indian was a dead Indian in the portrayals of the period. Indians were the "other," the designated enemy. Their culture was painted as the opposite of Anglo civilization, they attacked everything that good Americans were taught to revere. This bi-polar view of good and evil closely mirrored contemporary opinions about the relationship between America and communists.35 Even when toys or the media portrayed Native Americans as dignified and noble symbols of the lost virtues of the wilderness, they were still not shown as real people. People of colour inhabited a land of stereotypes in the minds of most white Americans.

42 In terms of child's play, astronauts were cowboys catapulted from the past into the future. The astronauts and their families even appeared to share this view. Trudy Cooper, the wife of astronaut Gordon Cooper, described telling Cooper's grandmother in Oklahoma of his new assignment: "She [his grandmother] went out there in 1895, when pioneering took a lot of spirit. When Gordon told her what he was on his way to do, she was so excited you would think the Indian wars were on again."36 Space, the New Frontier, assumed the mantle of modern wilderness.

43 Part of the dazzle and excitement of space was the prospect of winning the "space race" and establishing a base for galactic dominance before the U.S.S.R. Space was a frontier to be conquered as well as explored. Werner Von Braun, German rocket scientist turned American space expert, advocated the future construction of a space station. As reported by Life, Von Braun promised that a satellite station would "pay off as nothing has done since the time of the Roman legions. If placed in its orbit by the U.S., it will give the U.S. a permanent military control of the entire earth...No nation will attempt to challenge it; the earth will enjoy pax Americana and can beat its radar into television sets."37 When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I on October 4, 1957, Americans feared that the Communists had beaten them into space, and perhaps had gained an unassailable edge on world domination. Time called Sputnik "Red Moon Over the U.S." and labelled it "a giant step toward the conquest of interplanetary space."38

44 Space toys captured both the dramatic tension of the space race and the desire to couple exploration with conquest. United Nations Constructors' "Space Chase" board game and Ed-U Cards' "Satellite Space Race" card game clearly communicated the contest between cosmonauts and astronauts to be first and foremost in space. Toys like Monogram Models' "First Lunar Landing Module" and Hasbro's "G.I. Joe Space Capsule" celebrated American victories. Play astronauts could arm themselves as extravagantly as would-be cowboys with space ray guns, atomic pistols, phasers, and other futuristic weaponry. Louis Marx and Company's "Cape Canaveral Play Set" offered a full miniature base, complete with mission control building, wire fences restricting entry, armed sentries, rockets and launching devices, scientists, and astronauts. A 45-rpm record of rocket launching noises was also available for purchase. The set clearly placed the space program as a link between science and defense.

45 The space program represented the effort to conquer technology as well as the cosmos. The popular press lavished loving descriptions on the exotic and elaborate hardware that accompanied the astronauts into space, and on the computer technology that got them there. Toy manufacturers kept pace with Boeing and their competitors. Toy rockets were equipped with special propulsion devices, and junior astronauts could carry communicators and hand-held scanners that could detect life forms or stun or kill assailants.

46 If cowboys and Indians represented reliving the mythic past and space men symbolized the hopeful future, then war toys, particularly the spectacularly popular "G.I. Joe," miniaturized the cold war present. While the war was "cold," the embers of World War II engagements still glowed and the threat of communist aggression kept the military-industrial complex warm. The Korean and Vietnam wars made military service a real possibility for boys playing with war toys in the 1950s and 1960s.

47 It was natural that children wanted war toys since popular magazines like Life functioned as advertisements for the products of the defense industry. Cold war America glorified weapons of destruction. A two-page color spread advertised new United Aircraft Corporation products: "Yes," it declared, "after more than ten years of intensive effort by the military, scientists and technicians from industry and from universities, guided missiles are indeed coming of age."39 A two-page color ad for Grumman fighter jets displayed a painting of combat planes dropping bombs on Korea. For the price of a brief letter and a stamp, Grumman offered that "a full-color reproduction of this advertisement without text and suitable for framing will be sent to you for the asking."40

48 The ads selling the defense budget, encouraging voters to fund one new fighter jet after another, were entirely consistent with the exaltation of consumption that influenced all aspects of the economy, particularly the toy industry. The pamphlet included with each G.I. Joe sold in the 1960s told buyers, "You don't need everything at once to enjoy the pleasure that comes with collecting G.I. Joe equipment...In other words, start small and grow big — and have a happy time doing it."41 Having "a happy time" was as much a matter of shopping as it was playing, for G.I. Joe owners as well as for their sisters with Barbie collections.

49 Superficially, G.I. Joe was a glaring contrast to Barbie's Ken. Hasbro made sure to label G.I. Joe an "action figure" when they first introduced him in 1964, since the values of the period would not allow boys to play with dolls. As noted above, however, G.I. Joe joined Ken and Barbie as models for consumption. None were complete with the first purchase of the doll: all required a multitude of accessories, all to be "purchased separately" in order to play with the full range of possibilities. While Ken had cardigans and water-skiing outfits, G.I. Joe had his Navy uniform, his Marine dress uniform, his M.P. uniform, his Carrier Signalman, and Firefighter uniforms, among many others.

50 As descriptions of military hardware graced the ads and text of popular magazines, the lines between the battlefield and the household blurred. In a period of great political stability and prosperity in American society, war was a part of everyday life. It was just as natural for little boys to play soldier as it was for them to play fireman.

51 According to manufacturers' intentions, girls were to play only subordinate roles in these games. They could be wives of astronauts, girlfriends of cowboys, or damsels in distress — the same kinds of secondary positions that the dominant culture prescribed for their mothers. Stanley Breslow, the big pistol and holster manufacturer, discussed how his company made "special sets for girls, mostly in red-and-white leather."42 Boys' sets were made to look fierce, authentic, and deadly; girls' sets were ornamental. L. Quinlan, Jr, the president of A. C. Gilbert, a company producing science kits and erector sets, stated, "Let's face it, a little girl's future problems are men, and she should be taught how to face and fight them."43 In other words, the lessons learned from science and construction toys were lost on her; what she needed were toys that encouraged popularity with boys and housekeeping skills.

52 Despite their "proper" role, girls often took part — as equal a part as their brothers would allow, or their own force of character could win — in boys' games, but boys rarely reciprocated by participating in girls' play. Psychologist Brian Sutton-Smith found that from the turn of the century to the 1960s, girls' play became more and more similar to boys', but "boys have been steadily lowering their preference for games that have had anything to do with girls' play."44 Literary critic Jane Tompkins wrote about how girls easily learned to assume a variety of roles:

53 Toys did not reflect the reality that in 1955, 22 million American women worked outside the home,47 nor were most men even remotely involved with space flight, fighting Indians, or armed combat. Popular toys symbolized the stereotypes that emphasized the extreme polarities between prescribed male and female behavior. Barbie's big breasts and G.I. Joe's big guns were equally unreal — but equally revealing. The exaggerated images of the fertile domestic woman and the aggressive male captured the lack of nuance and complexity in the era's gender roles. Despite the discrepancies between stereotypes and reality, the stereotypes had force and significance. They defined the limits of acceptable aspirations. Their narrow vision of what men and women could be effectively discouraged many young men and women from challenging these boundaries.

54 There was a parallel dichotomy in early cold war politics that divided the world into communist enemies and anticommunist allies. Many Americans believed that the ultimate sign of a "free" society was an active free market, leading to a conviction that avid consumption was a proof of democracy. Toys both reflected and bolstered this opinion. They represented the era's dedication to consumption as they communicated the values of the consumer society to the baby boom generation.