Articles

Tompkinsville, Cape Breton Island:

Co-operativism and Vernacular Architecture

Abstract

Cape Breton Island's architectural landscape has a high percentage of "company housing" built for coal miners and their families in the early years of the twentieth century. By the 1930s, some of these dwellings were in poor condition. This paper examines one group of miners and their families who decided to embark on their own co-operative housing project in the 1930s, following the philosophy of the Antigonish Co-operative Movement. It explores how this group, while being prompted by a motivation to escape from the poor conditions of the company houses, chose to live in spaces familiar to them, following some of the spatial patterns common in the company houses. This housing development was very influential; it was the first co-operative housing group in Canada and provided a template for other comparable housing developments in eastern Canada.

Résumé

Le paysage architectural de l'île du Cap-Breton comporte un pourcentage élevé de « logements de compagnies » construits pour abriter les mineurs de charbon et leurs familles au début du vingtième siècle. Dans les années 1930, certaines de ces habitations étaient en mauvais état. L'article porte sur un groupe de mineurs et leurs familles qui ont décidé de lancer leur propre coopérative d'habitations dans les années 1930, suivant la philosophie du Antigonish Co-operative Movement (mouvement coopératif d'Antigonish). L'auteur étudie comment, malgré sa motivation d'échapper aux mauvaises conditions des logements fournis par les entreprises, ce groupe a choisi de vivre dans des espaces qui lui étaient familiers, en respectant certaines structures spatiales fréquentes dans les « logements de compagnie ». Ce projet domiciliaire a eu une grande influence; il constituait la première coopérative d'habitation au Canada et a servi de modèle à d'autres ensembles de logements comparables dans l'est du pays.

1 Joining together with one's neighbours to aid in a construction project or communal work activity was once an essential part of the fabric of Atlantic Canadian communities. Outside activities such as house raisings, barn buildings or chopping frolics to gather wood for a widowed member of the community or local clergy are frequendy mentioned in the region's autobiographies and oral histories; interior activities such as spinning bees, quilting bees and milling frolics played essential roles in the passing on of work patterns and oral traditions inside homes.1 Even though the issue of co-operativism is important for understanding the way in which communities and neighbourhoods are formed and maintained, this process has been largely unexplored in much of the literature on vernacular architecture.2 In this paper, I examine one neighbourhood of eleven homes in Tompkinsville, Cape Breton Island — a cooperative housing development begun in 1938 in the former coal mining town of Reserve Mines — to help unravel some of the complexities of this issue.

2 The term vernacular has been interchangeable in much scholarship with the terms folk, common, native or non-academic architecture. It is usually placed at the other end of the spectrum from professionally designed architecture or what is most often termed high style architecture. Vernacular buildings are often owner built; that is, the owner takes an active hands-on role in the entire process of designing and constructing the building, from deciding upon the size and shape of interior spaces, to obtaining the materials. One scholar, Kingston Heath, uses the analogy of a "filter" to define the vernacular in architecture. He argues that a fixed locale or region, with its unique character, cultural mix, values, materials, climate and topography can filter the conventional ideas about architecture whether they be folk, popular or high style. What results from this filtering process is vernacular architecture — "product of a place, of a people, by a people."3

3 A region or neighbourhood's vernacular architecture is an expression of the community's personality. Studying "regional personality," while not common in Canada, is a familiar idea to European folklife scholars and regional ethnologists. J. Geraint Jenkins, a Welsh ethnologist and museum curator, describes the domain of this field: "in folklife studies we are concerned primarily with the recording and study of regional personality, and features which distinguish one community from the other whether they be social, oral or material should be our concern."4 A region's needs, tastes and cultural expressions are shown in the way people design, build and use their homes and outbuildings; these are fine expressions of regional personality. Some features which make a neighbourhood a distinct region include the public spaces, the religious buildings and the local culture, but the houses people choose to build are extremely important in the shaping of a distinct, vernacular district.

4 Vernacular architecture has been studied in Europe for many years, but only in the past twenty or thirty years have North American scholars viewed it as an acceptable field of research.5 Folklorists, geographers, architectural historians and archaeologists are interested in vernacular buildings because they are said to provide a more democratic view of the remote and recent past than do the kinds of buildings traditionally studied in architectural histories. As Henry Glassie says: "historians study not the past but the literary remains of the past. Nevertheless, most of the world's societies have been non-literate. They left no literary remains..."6 In contrast, "the landscape is the product of the divine average."7 Vernacular buildings in the landscape are a rich source for those trying to understand the interaction of human beings and the built environment.

5 While few academic studies of Atlantic Canada's vernacular architecture exist, a number of popular studies of the region's buildings have recently been published. A few predominant themes appear in this academic and popular literature. Most popular studies, for example, are guided by the social history of a community; these publications are primarily pen and ink sketch books or photograph collections with a discussion of the history associated with the building owners. Historical societies, provincial government departments, municipalities and local museums are often responsible for these kinds of publications.8 One recent popular work deviates from this approach and attempts to survey the various types of Nova Scotia's working class housing from the eighteenth century to the present.9 While this is a valuable first attempt to examine the province's vernacular dwellings, the work suffers because the author possesses a nostalgic view that only building choices in the past were creative and intelligent, while more recent vernacular buildings are seen as uninspiring, government-sponsored imitations, lacking beauty and meaning.10

6 In the academic world, Adantic Canadian vernacular architecture has been dominated by cultural geographers and folklorists. Geographers have addressed themes such as architectural transfer, adaptation and change and have been interested in the influence of ethnicity on buildings. For example, Peter Ennals and Deryck Holdsworth propose an overall typology of buildings for the region, outlining some of the major architectural forms evident in the Atlantic landscape.11 Peter Ennals has also assessed Acadian architecture, documenting both the earliest known forms and the recent Acadian interest in replicating eighteenth-century Québécois buildings.12 John Mannion has explored the persistence, modification and alteration of Irish architecture and material culture in the Atlantic Canadian region.13

7 Folklorists have provided vernacular architecture micro-studies of some specific sub-regions within Atlantic Canada exploring issues such as architectural transfer and change, the contrast between tradition and modernity, gender and spatial usage and the patterns of modification.14 One of the most important studies of Adantic Canadian vernacular architecture and landscape is a recent analysis of the homes, outbuildings and spatial usage in the Newfoundland outport of Calvert.15 This work is the first of its kind in Atlantic Canada to employ current methodological and theoretical approaches from the fields of material culture and folklife to interpret the shaping of the built environment of a coastal community.

8 Architects, archaeologists and architectural historians have also been interested in the vernacular architecture of the region. Alan Penny, a professor at the Technical University of Nova Scotia, has recently published a style guide to Nova Scotia's architecture that includes many examples of the region's vernacular forms.16 André Crépeau and David Christianson, archaelogists at the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Park, have been exploring pre-expulsion Acadian vernacular architecture in their recent fieldwork.17 H. M. Scott Smith's two recent works on Prince Edward Island architecture, one focussing on the region's churches, and the other on its domestic housing, likewise provide the reader with photographs, floorplans and fine descriptions of the island's many distinctive architectural features.18

9 This present study of Tompkinsville employs a methodological approach developed by vernacular architecture scholars that includes: the recording of buildings through photographs, measured drawings and interviews with residents, and a reliance upon fieldwork and research to understand the architectural patterns in the landscape.19

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1The Influence of the "Antigonish Movement" on the Tompkinsville Housing Development

10 In deciding to work co-operatively to build their homes, Tompkinsville pioneers were following the co-operative philosophy expounded by what is now known as the "Antigonish Movement." This movement was a social and economic reform movement begun by priests working at St Francis Xavier University in Antigonish. Two of the founders, Father Jimmy Tompkins and Father Moses M. Coady led the movement to local, regional, national and international significance. The founders and leaders believed that individuals could raise themselves from economic plight and become better physical, moral and spiritual beings through adult education and co-operation. They envisioned that individuals in small study clubs could solve their own difficult problems through co-operative study and work. Libraries, credit unions, grocery stores, gasoline stations and co-operative housing groups grew out of this movement in Atlantic Canada.20

11 The Antigonish Movement attempted to promote education and co-operation in the early 1930s, a time of great hardship in Cape Breton Island. These feelings of discontent in the thirties were provoked by the struggles of the previous decade. The 1920s were hard, bitter years of great unrest amongst workers of Cape Breton Island. The decade saw numerous strikes in the coal industry and sharp class conflict; a culture of resistance amongst coal miners resulted from the workers' struggle with industrial capitalists.21 One scholar notes there were at least fifty-eight strikes in the Sydney coal field between 1920 and 1925, "most of them over not wage issues but such matters as work assignments, fines and suspensions, and the role of the pit committees and the union within the workplace."22

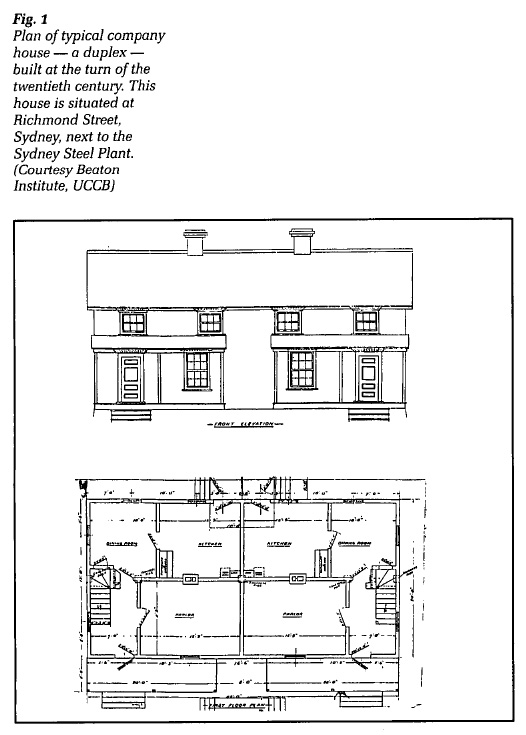

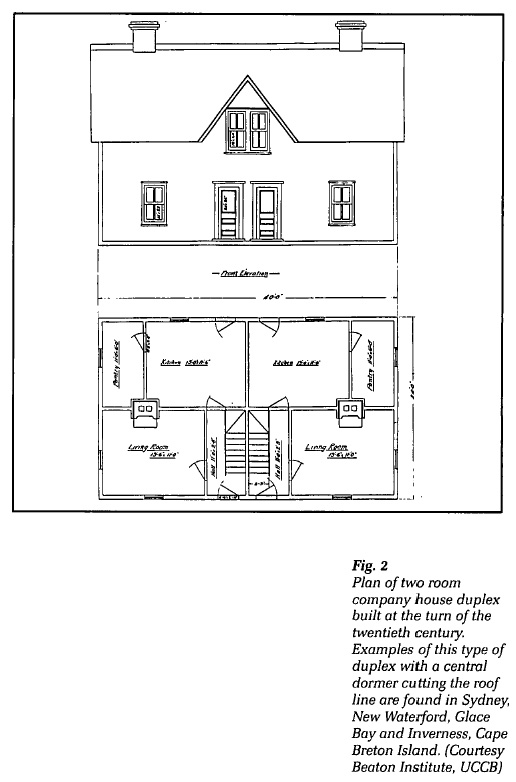

12 Workers were also unhappy about their living conditions. Some of Cape Breton's coal miners and their families were housed in poorly maintained, dilapidated duplexes built by mining companies at the end of the nineteenth century. A Royal Commission on Coal in 1925 interviewed a number of Cape Breton miners about their homes and one mentions to the commissioner, "there was three rooms downstairs: kitchen, dining room and front room. Upstairs there was two bedrooms, but there is other two holes in the wall. I would not exactly like to call them bedrooms, they are too small, one you cannot get a bed in at all unless you saw it off."23Three room and two room plans were the norm for early twentieth-century company housing throughout the Cape Breton industrial region (Figs. 1 and 2). Mary Arnold, a New York housing reformer who played a significant role in the Tompkinsville housing development, outlines conditions in the 1930s: "It is difficult to tell one house from another. If you are a comparative stranger in Reserve and wish to visit a friend, you take the nearest telegraph pole and count down from it two, three or four houses as the case may be. All the houses are painted a dark green or brown..."24 While similar in style, many houses were also in poor condition with no cellars, rotted sills and badly constructed windows and doors:

These duplexes were over seventy-five years old with shingles painted dark green or with unpainted clapboards. There were no indoor toilets, and the front and back yards were dusty and dirty. The rent charged by the mining company in 1938 was ten dollars per month.26

13 A survey of housing conditions in the early 1940s, done with the assistance of a representative of the United Mine Workers of America District 26 and the local municipality, verifies the poor conditions faced by miners and their families. The survey of 320 dwellings in Reserve Mines showed that 1 799 people lived in these houses and that eighty-eight per cent had no bathroom or indoor toilet, no sewer system was developed in the community and forty-seven per cent of the houses were over fifty years old.27 Of the 320 houses, 159, or forty-nine per cent, were considered overcrowded and there were at least thirty "shacks," temporary houses found around mine sites which were deemed "uninhabitable."28 The report concluded that 125 to 150 new housing units were required for the community, that a sewage system needed to be installed and that the community should provide for individual ownership, co-operative ownership or subsidized low rental limited dividend corporation projects.29

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 214 Moreover, the report petitioned the Premier and Minister of Highways of Nova Scotia, Angus L. MacDonald, about the deplorable conditions of roads in the community. The worst conditions were said to be in the neighbourhood where many of the Tompkinsville pioneers originally lived:

This survey indicates that available housing and conditions, particularly in the company-built rows, were inadequate for miners and their families. The poor conditions helped to steel the resolve of the miners to search for solutions to their housing problems. The cooperative Tompkinsville experiment was one innovative approach to solving this fundamental problem.

15 This was the social context the leaders of the co-operative movement faced when attempting to persuade coal miners and their families to work co-operatively. Father Jimmy Tompkins, born in Margaree, Cape Breton Island on 7 September 1870, is the foremost founder of the Antigonish Movement.31 Dr. Moses M. Coady, co-founder of the movement, was twelve years younger than Tompkins. He has been called "a devoted priest, a zealous apostle of the social order — a magnetic leader.. .who showed thousands of people throughout the world...how to become masters of their own destiny."32 In Reserve Mines, Father Jimmy Tompkins was influential; he provided the idea for cooperative community enterprises and the innovative housing experiment of Tompkinsville now bears his name.

The Development of Tompkinsville, Cape Breton Island

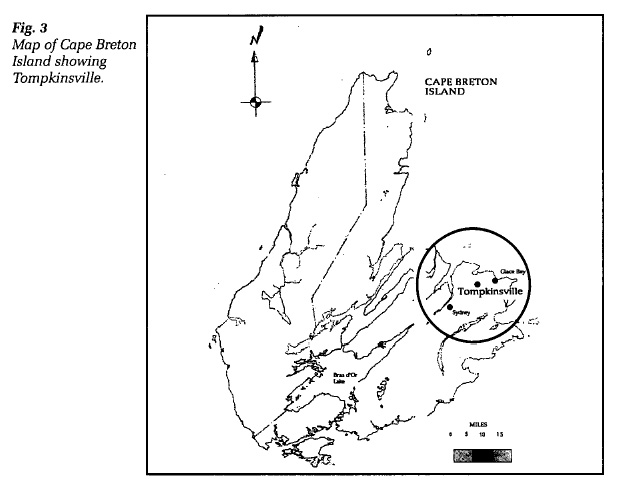

16 The neighbourhood of Tompkinsville, in the heart of the Cape Breton mining district, exhibits some features of vernacular architecture (Fig. 3). This neighbourhood development was begun in 1938 by miners and their families who were dissatisfied with the inadequate housing provided by the resident mining companies. Following the co-operative philosophy expounded by Father Jimmy Tompkins, their resident parish priest, the miners and their families formed study groups and taught themselves to build houses suited to their specific needs. This was the first co-operative housing group in Canada and was used as a model for the construction of numerous housing developments throughout eastern Nova Scotia from the late 1930s until the 1960s. Much of the architectural landscape of Cape Breton's industrial communities in the 1940s,' 1950s and 1960s was shaped by cooperative housing groups following the pattern worked out by the early Tompkinsville residents.

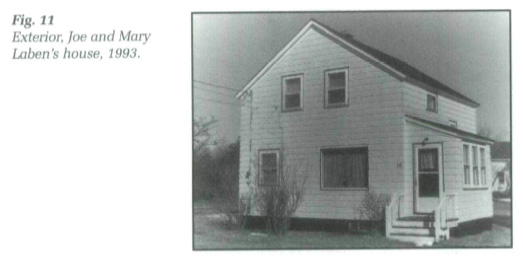

17 While the Tompkinsville houses were built in 1938, preparation actually began a few years before. Establishing a Credit Union in the community was the first experience some of the miners had with the co-operative philosophy. A Credit Union study club was organized in October 1932, with Joe Laben taking a leadership role. After much reading, thinking and discussion, the first credit union was started on 2 March 1933 with forty-three members and a share capital of $37.33It was difficult at first to get some miners interested in the study groups. As Mary Arnold says, "You couldn't do anything with some fellows. They never read anything or seem to care. They don't even know what Father Tompkins or Father Coady are talking about..."34

18 By the mid-thirties a number of Reserve Mines residents accepted the ideas being presented by Father Jimmy Tompkins. Mary Laben describes Father Tompkins' influence on the community:

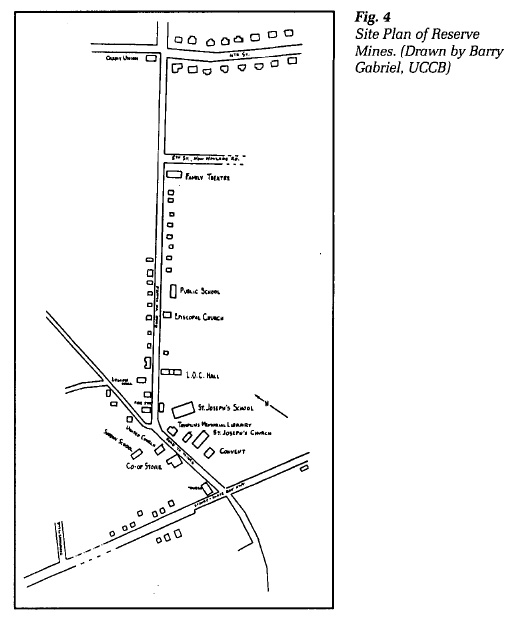

In 1935, as Mary Laben points out, the first community library was established with the assistance of Dr. Jimmy Tompkins (Fig. 4). It was located in the front room of St. Joseph's Rectory, situated next to the Roman Catholic Church in the centre of the community.36 As Tompkins said, "Read. Books are the university of the people. Ideas have hands and feet. Choose your ideas. They will work for you. You must study."37 In this Reserve Mines library, the team of co-operators were introduced to many texts on co-operativism, self-worth and the industrial revolution. Mary Laben explains this process:

By the fall of 1936, a small group were working on the establishment of a co-operative store. On 8 November 1937, the co-operative store, for miners and their families, was opened in the community of Reserve Mines and located across the street from the church and convent. It provided an alternative to the company stores which had dominated the mining communities until this time.39

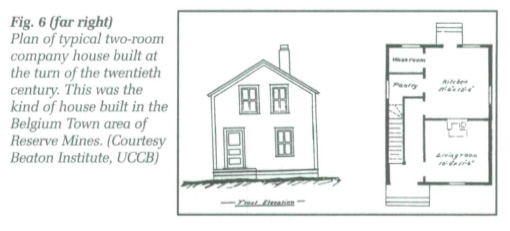

19 In the fall of 1936, a land study was started by a group of men who met every Sunday at Joe Laben's company house in a neighbourhood called Belgium Town, where many immigrant families resided (Figs. 5 and 6). Mary Laben describes her house in Belgium Town:

The notes from the group's meeting says, "At first it was hard to get a crowd to stick."41 Five miners attended the first meeting: Joe Laben, the president; Ray McNabb, treasurer; Ed Kelly, secretary; and John Smith and Mick Gardner. This club studied pamphlets such as The Industrial Revolution, Consumers Co-op, Why Workers Should Be Co-operators, published by American co-operative agencies. Each member had to make a speech at an appointed time of each meeting. Their notes indicate that "the questions were very interesting and helpful to keep crowd together" and that "speech making was well liked" by the assembled group. Books were being circulated from the community library and individuals enjoyed discussing their contents while learning much about cooperative principles and values.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 620 It was not until the group had established a credit union, a co-operative store and a community library, that a housing project was first considered. A housing study club was organized in the spring of 1937 and, following the same format used with their previous cooperative successes, the club studied many issues relating to housing. Mary Laben explains what happened:

One of their first tasks was to make a careful study of the Housing Act of Nova Scotia. At this stage of the project, two outsiders, Mary Arnold and Mabel Reid, co-operative organizers from the United States, came to assist them in their proposed endeavor. Connected to the St Francis Xavier Extension Department, these social reformers offered to help the group. The group accepted the two women as manager and assistant manager, respectively, because of their previous experience with co-operative housing developments. Mary Laben describes how Mary Arnold came to Tompkinsville:

At once, they began to plan for their proposed homes and to bring their wives together with Mary Arnold and Mabel Reid to plan for the interior layouts.45 Mary Arnold stayed in Reserve Mines for more than one year during construction and helped with planning, organizing, bookkeeping, and building cardboard models of the homes.46 Reformer, builder, cooperator and manager of apartments, Mary Arnold assisted in numerous ways in the completion of this housing group. The group decided to use a contractor to build the first house, to allow them to observe the building process and to assess construction time, costs and materials. Mary Arnold says, "Let the contract for a budget house to a reliable builder, got the total cost of such a house built under contract conditions, made it similar in every way to the houses which the men planned to build, and then cost accounted every joist and every sill of the budget house as well as every hour of work by skilled men.. .We could obtain accurate figures against which we could check labor and materials in the houses built by the men..."47 This first house in the neighbour-hood was where Mary Arnold lived during her stay in Reserve Mines.

21 Joe Laben, the president of the housing cooperative, took a leadership role in this housing development; he was smitten with the cooperative philosophy, especially after Father Jimmy Tompkins became the parish priest in St. Joseph's Parish, Reserve Mines on 10 March 1935.48 After two years of weekly studies of carpentry, plumbing, electricity and general house construction, Joe, his wife Mary and each of the men and their families had completed a small, cardboard scale model of the houses to be built. As Mary Laben describes, the women played a key role in this whole process:

Men and women jointly helped to construct the houses. As Mary Laben says:

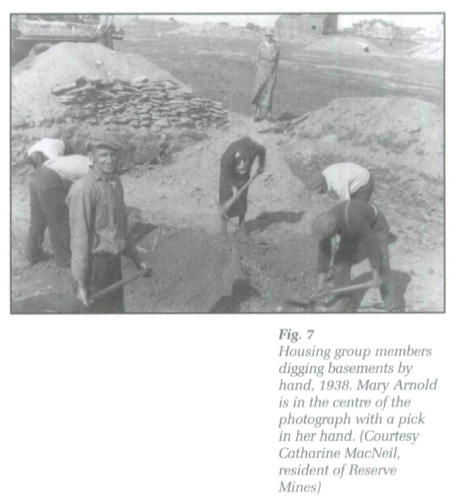

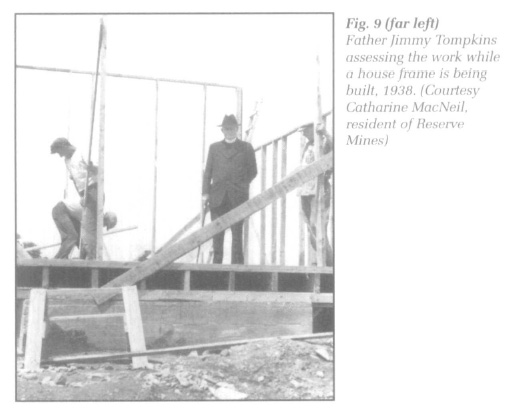

On 1 April 1938, group members started digging the first basements by hand and the cooperative housing experiment was becoming a physical reality (Fig. 7). The members aimed to build their homes for $500; at the time a comparable house, built by a private contractor, cost approximately $10 000.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 722 A travel writer, Clara Dennis, stumbled across the Tompkinsville housing group in her travels throughout Cape Breton Island in 1938. She met one of the Tompkinsville pioneers, George Clarke, at work on his home and she quotes him describing how the group was formed:

After examining the law for almost two years, the group studied housing, planning and all aspects of building; in a sense, they taught themselves the whole process of planning, designing and building houses from making forms and concrete foundations to framing and roofing houses. As George Clarke says:

Juggling the difficult shift work schedules, the miners proceeded to complete the project within one year.

23 To learn the intricacies of the Housing Act of Nova Scotia, Joe Laben attended a conference at St Francis Xavier University in Antigonish. There, he met Mary Arnold and her colleague, Mabel Reid, Americans who had been involved in housing co-operatives in New York City. The women offered to assist by lobbying politicians to change the legislation to better accommodate working people. Mary Arnold spent a year in Tompkinsville while the housing experiment was being built offering advice and assistance in whatever way she could.

24 Finally, on 27 November 1938, the group's dreams were realized when the housing development was completed. The terms of the mortgage were quite simple; one quarter of the total project's value was needed for the down payment. The group used their donated land as collateral for this loan. The government loan was rated at 3.5 per cent per year and their local credit union put up the balance of 1 per cent. The initial term was for twenty-five years but the group paid off their mortgage within twenty.53

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 825 While the project was progressing and after its completion, Joe Laben was invited to assist other co-operative housing developments in communities throughout Nova Scotia.54 For more than three years he travelled the province assisting in co-operative projects. Mary, his wife, worked at the Sydney airport managing the food services for Cara Enterprises while Joe continued to teach others about the benefits of co-operative housing. Because of his knowledge and wisdom, Joe was asked by St Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, to assist in their extension work and to lecture at the Coady International Institute on the issue of cooperative housing. Mary Laben discusses some of the groups Joe helped:

There was much interest in Nova Scotia in this innovative project begun by this group of Reserve Mines coal miners. A survey of cooperative "housing groups," as they are known in Nova Scotia, indicates that between 11 March 1938, when the Tompkinsville experiment began, and 16 July 1952, there were thirty-five housing groups developed in the province.56 Cape Breton communities such as Glace Bay, New Waterford, Inverness and Sydney built co-operative housing. On the mainland, communities such as Stellarton followed in the cooperative spirit.57 From 1953 to 1973, there were 982 co-operative housing projects developed in Nova Scotia.58 Joe and Mary Laben's house in Tompkinsville became a visiting site for Coady International students and for anyone interested in co-operative housing. Over the years, Joe received a number of awards for his contribution to the well-being of his community and of Canada, including the Centennial medal in recognition of valuable service to the nation in 1967; an Antigonish Movement service award in 1974; a visit from the Governor General of Canada, Ed Schreyer and his wife in 1982; and the Order of Canada in 1985.59

The Houses

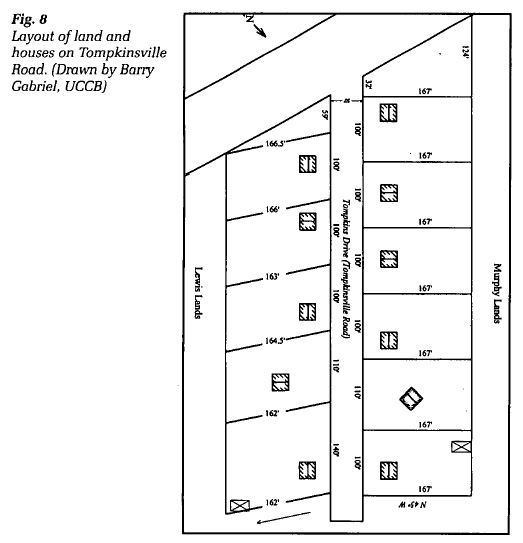

26 The eleven houses in this neighbourhood were laid out in a block of land originally designated for the parish graveyard and situated approximately three hundred yards from the centre of Reserve Mines where the church, convent, library, credit union, company houses and store are located (Fig. 8). Tompkinsville Road was driven in at a diagonal off the highway which runs between Reserve Mines and Sydney and the land was divided in a grid-iron fashion. Each house was situated on a piece of land on average 100 by 165 feet in size. Nine of the eleven houses were placed close to the road, leaving room behind for gardens; only one house, on the northwestern side, deviated from this arrangement — it was situated in the centre of the lot. Another house on the southeastern side of the neighbourhood was situated in a different manner from the rest — it was rotated forty-five degrees and placed closer to the centre of the lot. The co-operative group hired a contractor for this first house to be constructed, which allowed the residents to assess the length of time for building and to compare prices for materials and labour. Mary Arnold lived here when she was assisting residents of the neigh-bourhood with the construction of their homes.

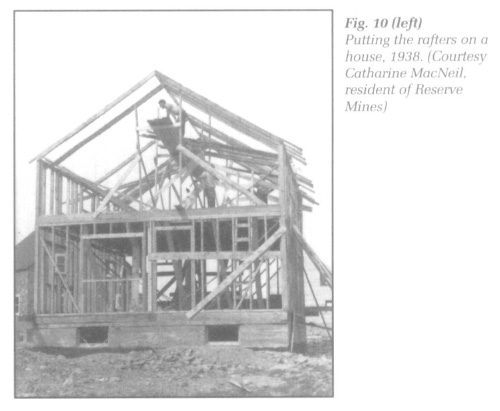

27 Ten of the eleven builders chose to construct gable roofs; only one used a half-hipped form, known locally as the "Cheticamp Style," because of its popularity in the rural Acadian community of Cheticamp on the western side of the island.60 Five of the eleven houses were built with the gable facing the Tompkinsville road; six were built with the long side of the houses facing the road. Each Tompkinsville house was two stories in height and had a bathroom and six rooms, including a kitchen, dining room and living room on the ground floor and three bedrooms upstairs (Figs. 9 and 10). Each house was unique with no two houses exactly alike in floorplan or decoration, although all chose the three-room ground floor plan for their living space. One of the pioneers succinctly summed up the minor variations:

Although the process of construction was communal and the floorplans were similar, individual builders were innovative in their use of cosmetic details and interior arrangements.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1028 The owners were proud of their accomplishments and allowed many visitors from Cape Breton Island and beyond to see the fruits of their labour. The interiors were brightly colored, causing one traveller in 1938 to focus on the cosmetic details of the visited house:

While both men and women helped construct the homes, women made the primary decisions on the cosmetic details of the house interiors. Travel writer, Clara Dennis, describes the spacious and well laid out kitchens:

This passage points out the way in which the members of this housing group were able to alter their individual spatial layouts in this all important room — the kitchen — the place where much activity occurred.

Display large image of Figure 12

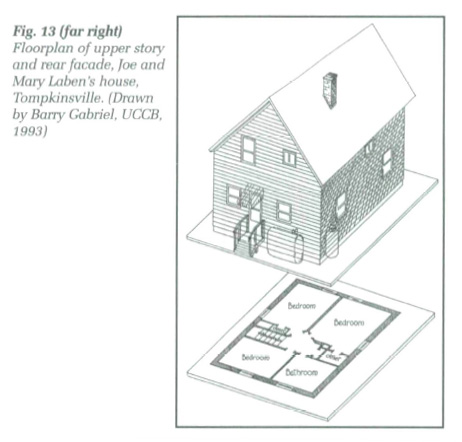

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

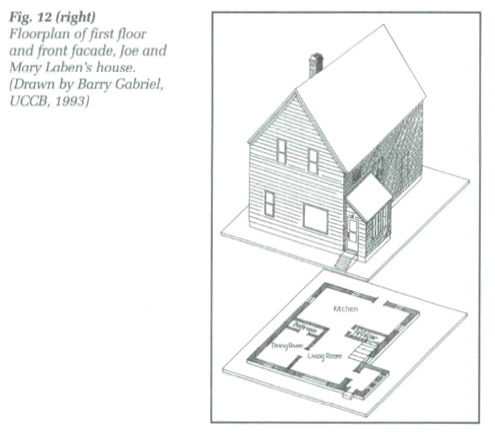

Display large image of Figure 1329 On my first visit to Tompkinsville to visit Mary Laben, the last surviving pioneer of this neighbourhood, I was welcomed into her comfortable, sun-filled kitchen at the rear of the house (Figs. 11,12 and 13). She said, "I love my kitchen" and she proudly showed me around pointing out its many features and details including a sunny kitchen nook with table and chairs, a large space for cooking and a wall of cupboards for storage.

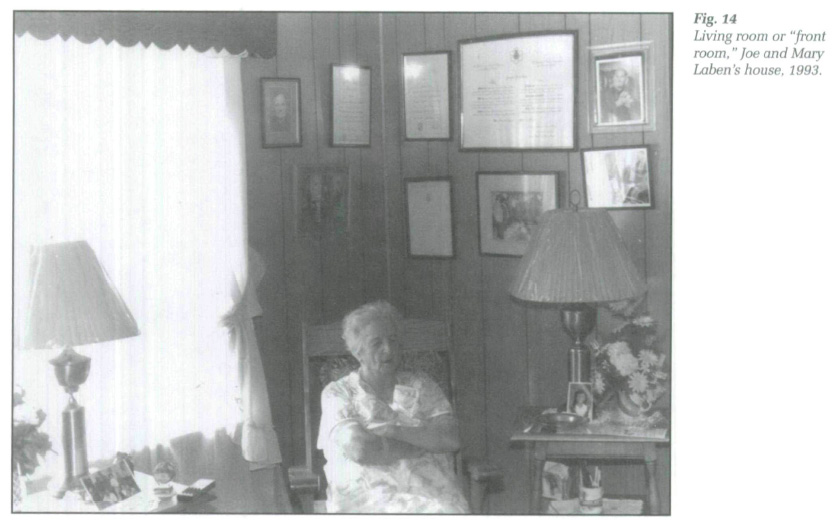

30 While the rear kitchen is sunny and inviting, the "front room" or living room is where the many photographs of daughters, nieces, their friends and acquaintances and Mary Laben's husband, Joe, are displayed. The photographs in this "personal museum" show the various rites of passage of family members and the awards offered to Joe Laben for his contribution to co-operativism and housing (Fig. 14). It is here where special guests are invited and where Mary Laben now spends much of her time. The influence of the Roman Catholic faith of Mary and her husband is also demonstrated by the large image of The Last Supper and a photograph of Christ overlooking the living room.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 1431 The Laben floorplan has a kitchen to the rear, a living room, or "front room" as it is most often called in Cape Breton, at the side of the house facing the road, and a small dining room which has been transformed into a small bedroom. The dining room now functions as a bedroom for it is difficult for Mary Laben to get up and down the stairway, which leads from the living room. A small bathroom was built off the dining room for Joe Laben when his illness in the last ten years made it increasingly difficult for him to climb the stairway. The upstairs contains three bedrooms with small closets along with a small bathroom.

32 While Joe and Mary Laben's house and those of their neighbours were built co-operatively as a response to company domination of housing, it is ironic that residents chose familiar spatial patterns when deciding to construct their new houses. A variation on the gridiron plan was used to lay out their neighbourhood, a common town plan used in the many coal mining towns of Cape Breton and in other areas of North America.64 Even though their motivation for building co-operatively was to move away from the company housing, owned and managed by the Dominion Steel and Coal Company, they chose a basic three room plan with a front room, dining room and rear kitchen when selecting suitable spaces for their new houses. This plan made its appearance on the island in the various company houses built as early as the 1830s by the British-owned General Mining Association. While two room plans of kitchen and front room were used in Cape Breton's company housing, particularly in the Belgium Town area of Reserve Mines where Joe and Mary Laben resided before moving to Tompkinsville, by 1900 the standard plan in company duplexes built by the Dominion Steel and Coal Company was the three-room form. Homes of this type can still be found in communities such as Dominion, Glace Bay, New Waterford, New Victoria, Sydney Mines and Inverness as well as in Reserve Mines. Even though the company houses from where the residents originally lived were considered to be sub-standard, the builders of Tompkinsville demonstrated conservatism in selecting a familiar floorplan for their new homes.

33 Moreover, Mary and Joe Laben also chose to build a home with a gable facing the road. While many of the early and mid-nineteenth-century company houses were attached rows, copying British mining housing, the early twentieth-century single family company homes were gable-entry-to-the-road homes. The gable front house with a main entrance off to one side on an end gable, is said to have emerged in North America by the 1830s.65 The house type grew largely from the late eighteenth-century interest in classical forms, which promoted the architectural style called classical revival, so popular in religious, public and domestic buildings from the 1820s until the 1860s.66 Allen Noble point out that orienting the gable to the street allowed narrower and less expensive urban town lots to be used by builders. By locating the gable facing the street, more buildings could be placed in smaller geographic spaces.67 Thomas Hubka points out that New England farmers readily accepted this form into their building repertoire after the 1830s, at a time when there was considerable reorganization of space on New England farms.68 Moreover, he argues the primary appeal to Americans of the classical movement was nationalistic; this architectural style became a symbol of the new American republic which was attempting to build a nation based on classical ideals: "The image of Greece and Rome became a symbol of progress..."69 This house type, without the classical details, appeared in Cape Breton mining communities at the turn of the twentieth century; it was this form that Joe and Mary Laben chose when deciding on a suitable home in their Tompkinsville neighbourhood.

34 While following a familiar local pattern of interior spatial usage, Tompkinsville residents also followed familiar land use patterns in their exterior yards. They planned for and planted gardens to help supply their families with fresh produce and root crops. The garden was not a hobby but a necessity for many, especially at times when the mines were reduced to one of two shifts a week, a common occurrence throughout the 1930s. Many of Tompkinsville's and industrial Cape Breton's residents have rural roots; some of their forefathers came from rural Inverness, Victoria and Richmond counties of Cape Breton in droves at the turn of the twentieth century when coal niining was booming on the island. The Tompkinsville residents grew root crops and vegetables in the 1930s to help feed ther families in difficult times. Mary Laben points out that in addition to beans, peas, carrots, squash, turnip and potatoes, their garden also contained a large patch of strawberries, which supplied more than twenty-five baskets each year.70

35 Numerous changes have happened in this neighbourhood in the last fifty-six years. Many of the original residents have died and younger citizens have purchased the homes of the Tompkinsville pioneers. There are no longer coal mines in Reserve Mines; men from Reserve Mines work in the underground submarine Phalen colliery in the nearby town of New Waterford. Many of the houses have been repainted and changed over the years with the most common renovations being the applying of aluminum siding and the replacing of windows in the 1960s and 1970s in an attempt to cut heating costs and to lower maintenance costs for the aging residents.

36 The Tompkinsville houses tell a story of innovation and conservatism. The cooperative nature of the planning and construction of the neighbourhood was a response to domination of housing by a mining corporation in a company town. This group of Reserve Mines coal miners were the first to apply some of the co-operative ideas of Tompkins and Coady to the building of homes. While innovative, these builders were also conservative in choosing familiar spatial patterns for their homes and yards.

37 The Tompkinsville housing co-operative exhibits many features of vernacular architecture. For example, the builders controlled the entire building process in this neighbourhood. Despite the poor economic climate, the owners saw that by working together to construct homes they were able to afford suitable, comfortable homes. This whole co-operative enterprise allowed mining families to break away from the confines of the company-owned housing so prevalent in the community at the time, yet they were able to use the spatial patterns with which they had become accustomed. This cooperative building process is, in itself, an older, conventional vernacular pattern. Barns, out-buildings and houses were once "raised" in many communities in a communal fashion with entire neighbourhoods of men, women and children assisting in some way. While neighbourhood residents were limited by costs and size, they also adjusted and altered their architecture to suit their own needs, modifying each unit to match the particular aesthetics of the family. The architecture of this neighbour-hood is clearly "product of a place, of a people, by a people."71

38 It is inadequate to simply define vernacular in a negative way by calling it non-academic, non high-style, unsophisticated or non-professional, for vernacular architecture exists when a people or a community have some element of control over their physical environment. When individuals are able to build homes, barns or neighbourhoods following older, conventional patterns in a region; when they are able to adjust and alter their architecture to suit their own needs; or when they are able to express their wishes and desires in making a home or building, we are dealing with architecture at the vernacular level.

39 This does not mean that only old and rural architecture is vernacular, although many vernacular architecture studies to date focus on older rural forms. Many urban houses such as those in Tompkinsville also exhibit vernacular features. Only recently have scholars begun to explore the vernacular aspects of contemporary housing. As Dell Upton and John Michael Vlach state, "Clearly more investigation of contemporary buildings, including commercial as well as residential structures, is needed."72

40 Joe Laben and his wife Mary played an integral role in the development of the Tompkinsville architectural experiment. They nurtured the idea of cooperative housing through many discussions and study clubs, through readings, conversations, arguments and debates. As Alex Laidlaw says, "Co-operation is not an easier way of doing things. It is a harder way by reason of its democratic methods. It is worthwhile not on the grounds of ease, but because of its humanism and because it is fair and equitable."73 These Tompkinsville residents moved from theory to practise as they constructed their own homes following cooperative ideals and their tenacious drive has transformed the many working class neigh-bourhoods in Atlantic Canada who have followed their example. Joe and Mary Laben's home remains a place to visit when one wants to find out about the development of cooperative housing in Atlantic Canada.

41 Architecturally, the Tompkinsville houses would not fare well if one evaluated them according to criteria developed by governments to assess the significant historical buildings in our communities. These houses are not extremely old, only fifty-six years. They are not designed by a well-known architect, they do not represent a unique architectural style and they are not directly associated with a prestigious merchant or industrialist. Moreover, they are sheathed in aluminum siding, a renovation made by many working class people throughout Nova Scotia in the 1960s.74 Nevertheless, the process of construction and the influence of this housing development at the local, regional, national, and indeed international levels, would suggest that the neighbourhood is a significant part of Nova Scotia's built heritage. Vernacular dwellings like those found in industrial communities throughout the country deserve to be represented more extensively in our historic building inventories and in our designated Canadian historic properties for they offer us a more realistic portrayal of the lives of working class Canadians.

Much of the material for this paper derives from the Beaton Institute Archives, University College of Cape Breton (UCCB), and the Public Archives of Nova Scotia. The most important materials, however, came directly from Mrs Mary Laben, the last surviving pioneer of this neighbourhood. She thoughtfully and carefully answered my endless questions about the development of the neighbourhood and allowed me to take measured sketches and photographs of her home. Mary and her husband Joe, who died in 1992, were two of the prime forces behind this housing development. Mary graciously offered her assistance throughout this entire project. I also wish to thank Kate Currie, Beaton Institute, UCCB, Ainslie White, Kim Stockley, Don Ward, Barry Gabriel, Bill Davey, Del Muise and the Nova Scotia Department of Culture to whom an earlier draft was submitted for their heritage Unit. An earlier version of this paper was also presented at the Folklore Studies Association of Canada annual conference at Carleton University, Ottawa, 2-6 June 1993.

Come and let us sing together, Hurrah to Tompkinsville!

They studied hard to get a plan the working man to suit.

They called on Doctors, Priest and Prince to see that they could do.

Among them all they worked a plan, to see their dreams come true.

The work was hard, the money scarce. We were a determined squad.

The blisters were big, our backs were sore, foundations were dug by hand,

But the project went right along.

And Hooker used to join him which would make it twice as grim.

John Allen watched while Kelly worked his garden every day

But he never grew a dad-blamed thing!

The benefits of group action here in this community

We've got our homes, a Credit Union and a Co-op Store

And a handsome Library.

The burning of the MORTGAGE, every cent is paid to date.

We did it all together, to help each other out.

And it only took us twenty years!