Articles

Machines in Suburban Gardens:

The 1936 T. Eaton Company Architectural Competition For House Designs

Abstract

Following the building industry's collapse during the Depression, Canadian architects saw the design of modest houses for middle-class clients as a means of professional salvation. This view was encouraged by a series of ideal home competitions held in 1936, one of which was conceived and promoted by Eaton's, a large department store. An analysis of this event demonstrates a fascinating mix of commercial and aesthetic agendas on the part of both the sponsor and the competitors. Like Canada's architects, Eaton's sought to develop new markets by using the competition to position itself as an arbiter of taste in matters affecting the middle-class householder.

Résumé

Après l'effondrement de l'industrie du bâtiment pendant la Grande Crise économique, les architectes canadiens ont entrevu une planche de salut dans la conception d'habitations modestes pour des clients de la classe moyenne. Ce point de vue a été renforcé par la tenue d'une série de concours sur la maison idéale, dont l'un était organisé et parrainé par la société des grands magasins Eaton. L'analyse de cet événement révèle que le commanditaire comme les concurrents poursuivaient un amalgame fascinant d'objectifs commerciaux et esthétiques. À l'instar des architectes canadiens, la société Eaton s'est efforcée de développer de nouveaux marchés en utilisant le concours pour s'ériger en arbitre du bon goût dans les questions qui intéressaient les propriétaires de la classe moyenne.

1 Following the collapse of the building industry during the Depression, Canadian architects came to see the design of relatively modest houses for middle-class clients as a possible means of professional salvation. They were specifically encouraged to do so by a series of ideal home competitions held in 1936. Two of these competitions were sponsored by the federal and the Ontario provincial governments, while the third was conceived and promoted by the managers of a large department store. Given the limited social role of department stores today, the T. Eaton Company's participation in efforts both to revitalize the moribund construction industry and to foster higher standards of design in the mid-1930s by means of a nation-wide architectural competition may seem somewhat surprising. While new house construction would logically lead to the purchase of new appliances and, perhaps, new furniture, the direct benefits of sponsoring an architectural competition in terms of sales of consumer durables would have been difficult to gauge. Hopes of counteracting a disastrous slump in consumer demand no doubt contributed to Eaton's decision to hold the competition, but arguably the choice of this particular promotional strategy was prompted even more by an ambitious vision of the department store's role in the cultural life of city and nation. The great retailer and Canada's architects had this in common: both sought to develop new markets by positioning themselves as arbiters of taste in matters affecting the middle-class householder. As an analysis of the Eaton's competition will show, there was a fascinating mix of commercial and aesthetic agendas on the part of both the sponsor and the competitors.

2 In common with other North American retail giants such as Macy's in New York, Marshall Field's in Chicago and Wanamaker's in Philadelphia, Eaton's was committed to an enlarged definition of the functions of the department store that included the entertainment and education of the customer, as well as the centralized distribution of a diversity of products.1 In a provocative essay Neil Harris has identified department stores, together with museums and fairs, as key social institutions actively seeking to form the tastes of the first generations of mass consumers.2 Conscious of the connection between the development of taste and the creation of demand, the managers of these stores deployed strategies ranging from sophisticated displays to art exhibitions to lectures in their efforts to legitimize consumption as a way of life. Services such as elegant restaurants and auditoriums helped to blur the distinction between the stores and other cultural attractions. To an extent that is now difficult to imagine, the great retail emporiums of the early decades of the twentieth century were a vital part of the aesthetic, as well as the commercial, life of North America's cities.

3 Eaton's College Street store in Toronto, which opened to the public in November 1930, reflected this sense of aesthetic and cultural mission. As originally planned by the Montreal-based architectural firm of Ross and Macdonald, the College Street building was to be a massive structure composed of a seven-storey plinth containing retail and customer service space, capped by an imposing office tower.3 This tower, with its New York-style setbacks, epitomized the confident mood of the late 1920s and, if built, would have served as a powerful symbol of Eaton's dominant position in the world of Canadian retailing. Unfortunately, the economic realities of a world-wide depression made it necessary to scale down the project; ultimately only the seven-storey retailing component was completed. Even so, the new store, which aimed at attracting well-to-do suburban shoppers to its convenient location at College and Yonge, was lavish enough to generate considerable excitement.4 A feature article catering to the public interest in the new building and its contents was justified by the editors of Canadian Homes and Gardens on the grounds of the cultural importance of such stores:

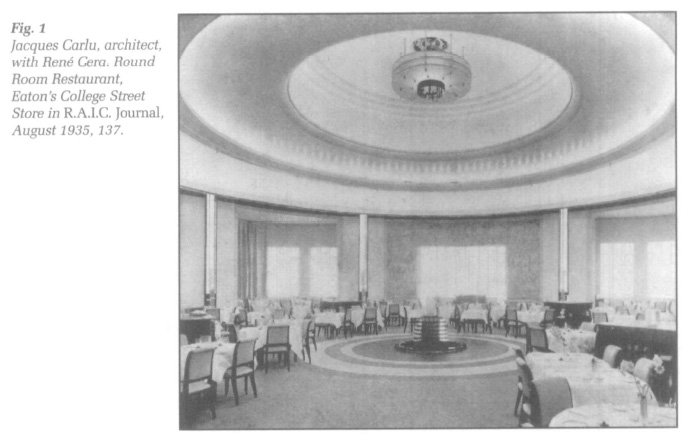

4 Boosterism aside, this tribute indicates that the department store's claim to be a centre for aesthetic education was taken quite seriously by other would-be tastemakers in Canada. That Eaton's managers were equally serious about instructing their customers in matters of taste is shown by some of the features incorporated in the new building: a series of period room settings modelled on the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, art galleries, a lending library, and an auditorium for public lectures and musical performances.6 The seductive appeal of these explicitly "cultured" elements was enhanced by the design of the building, which was heavily influenced by the luxurious art deco style first introduced by the Parisian Exposition des arts décoratifs et industriels of 1925. While the stripped down classicism of the store's exterior treatment conveyed an impression of conservative good taste, the use of modern materials and jazz-age decorative motifs in the interior was daringly fashionable. On the seventh floor, the auditorium and the Round Room restaurant, both designed by the French architect Jacques Carlu in collaboration with Eaton's in-house interior decorator, René Cera, were among the most sumptuous art deco interiors to be found in Toronto. Shoppers dining in the Round Room, widi its murals by Natasha Carlu, use of circular forms in both layout and decorative detail, and custom-built furnishings, received an education by osmosis in the taste and values expressed by art deco design (Fig. 1). It was an education that emphasized the continuity between earlier traditions of elegance and the luxurious simplicity associated with art deco's version of modernity.

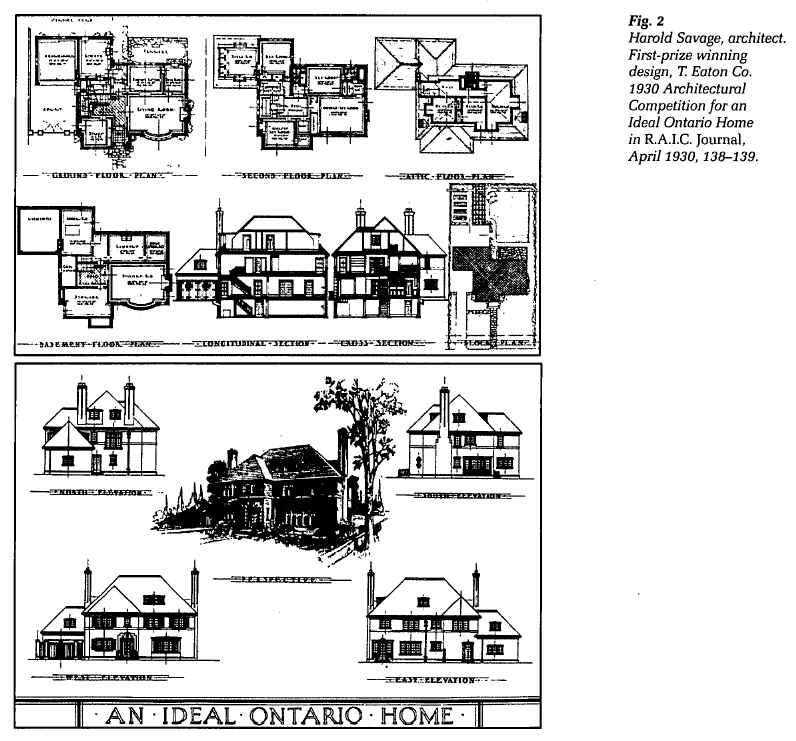

5 Beneath the veneer of education and entertainment, the period room settings and art deco restaurant had one ultimate purpose: the stimulation of consumer demand. Eaton's College Street store was built primarily to house the company's home furnishings division and the elaborate ensemble of displays and services provided at the new building was for the most part calculated to appeal to the upper end of the Toronto market.7 The desire to attract suburban householders with substantial incomes also motivated Eaton's first venture into the realm of house design competitions. In December 1929 the company announced an Ideal Ontario Home Competition "...open to all practising architects, architectural draughtsmen and students residing in Canada."8 This event, which called for the construction of the winning design on two floors of the College Street store, was an important feature of the promotional campaign leading up to the opening of the new building. Competitors were given a budget of $30 000 as a guideline; an amount that, in 1930, translated into a decidedly upper middle-class dwelling containing such amenities as a billiard room, a library, and servants' quarters. Toronto architect Harold Savage won the competition with a design that, according to Canadian Homes and Gardens, "...reflects certain modern treatment and restraint applied to a style reminiscent of the early Canadian farmhouse," (Fig. 2).9 It was, in fact, an essay in twentieth-century traditional design as influenced, perhaps, by Eric Arthur's recently published research into Loyalist domestic architecture. Savage's house would have been perfectly comfortable in the wealthy Toronto suburbs of the period.10

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 Just how comfortable can be demonstrated by a comparison with the exterior facades of the houses selected to illustrate William Lyon Somerville's article on recent domestic architecture in Ontario published in the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada [R.A.I.C] Journal in 1928. Somerville noted that two distinct solutions had emerged to the problem of the Ontario house by the late 1920s:

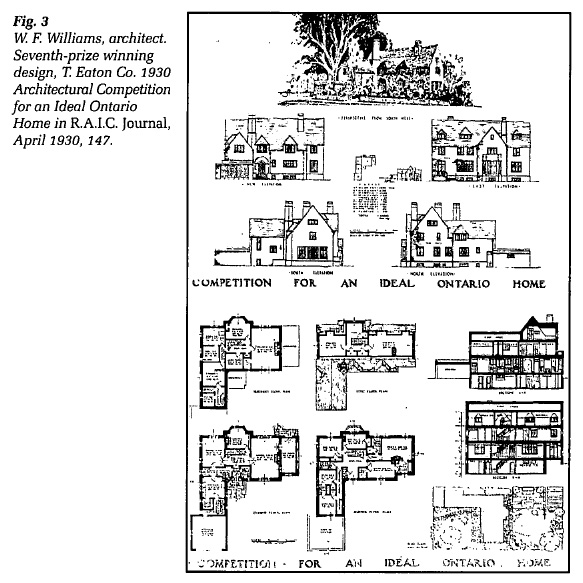

The justice of this observation is confirmed by the fact that almost all of the ten winning designs in Eaton's Ideal Ontario Home Competition fall into one of these two categories. To choose an example, W. F. Williams's house, with its "...small-paned leaded windows, spaced with interesting irregularity..." was representative of the entries tending towards the picturesque end of this rather limited spectrum of architectural possibilities (Fig. 3).12

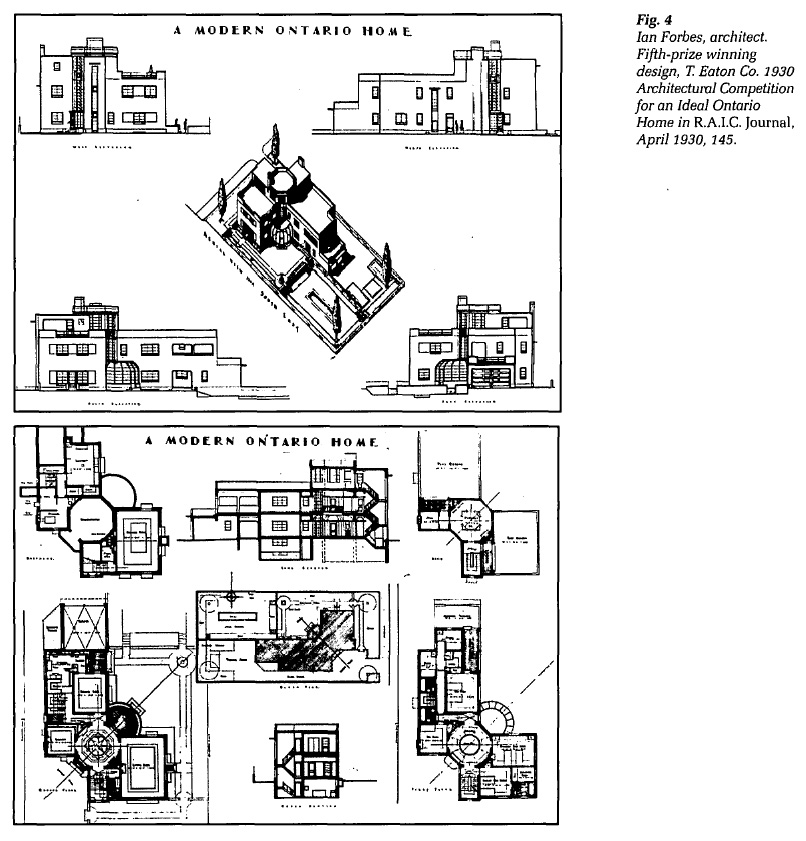

7 There was one striking exception to this general consensus: the fifth-placed entry submitted by Toronto-based architect Ian Forbes (Fig. 4). While their published comments were rather patronizing, the competition's three judges were clearly intrigued by the design:

In contrast to the work of his fellow competitors, Forbes's house was startlingly original in its emphasis on pure geometric forms. Two recti-linear wings were joined by a central octagonal tower that also served to anchor a third-floor penthouse nursery suite with roof gardens on two sides. The main entrance was a semi-circular porch enclosed by curving glass walls. Forbes's choice of materials was equally unconventional. The house was to be built of concrete, with steel window sashes and cast aluminum spandrels. Other specifications called for a heating system consisting of copper pipe coils set in the wall and floor concrete, and stainless steel hardware throughout.14

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 The "modern" approach to the problem of domestic design that had produced this anomoly was later outlined for the readers of Canadian Homes and Gardens:

According to the judges, however, Forbes's design failed in its attempt to address the third of these ruling factors. Later critics influenced by subsequent developments in Modern architecture might be more disposed to question both the plan and Forbes's notion of reasonable cost. His house is something of a paradox, consisting as it does of a formal arrangement of rooms with specialized functions that were becoming outmoded even in the early 1930s contained within a Modernistic shell that appeared to express avant garde rationalism.16 To a certain extent, this inconsistency can be excused as an artifact of the competition program, which demanded the inclusion of such Edwardian elements as a billiard room. Whether it was successful or not, however, Forbes's design was significant: alone among the competition entries, it indicated that a Canadian architect was willing to contemplate an alternative to the accepted suburban forms.17

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 39 The T. Eaton Company assembled a distinguished panel of judges for the 1930 competition: A. H. Chapman, president of the Ontario Association of Architects, Professor Eric Arthur of the University of Toronto, and Philip J. Turner, a Montreal architect who also taught at McGill University.18 In remarks summarizing their deliberations, the panel indicated that they had awarded thefirstprize to Harold Savage because his design offered the most successful solution to the problem of the house as an in-store setting for furniture display, not because it was a particularly interesting and innovative example of domestic architecture. Indeed, the three judges expressed a certain disappointment that the competition had not, as originally hoped, resulted in "...an outstanding design which could be called typically 'Ontario'..."19 On a more optimistic note, they concluded that the event had, at least, ".. .stirred up the profession generally, and we hope that as a result of this impetus, architectural design and particularly domestic architecture, will be finer and we hope more typically Canadian than before.20

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 410 Unfortunately these high hopes went unrealized. During the six years that followed, Canadian architects had little opportunity for further experiments in the area of domestic design. The deepening economic depression had its most serious effect on the building industry, and new housing starts decreased dramatically across the country. Expenditure on the construction of new houses dropped from $139 million in 1928 to $24 million in 1933. There were virtually no additions to existing housing stock in Montreal after 1931, and the situation in Toronto was not much better.21

11 Despite the gravity of the situation, in the years immediately following the 1929 stock market crash successive Liberal and Conservative governments adopted policies of minimal intervention in the economy, trusting that in time market forces would be capable of restoring prosperity. By 1935, however, R. B. Bennett, the Conservative prime minister, had reluctantly come to the conclusion that the federal government would have to take a more aggressive role. The spectre of an upcoming election, combined with the news of innovative measures being adopted across the border by President Roosevelt's Democratic administration, prompted Bennett to publicize the broad outlines of his own "New Deal" in a series of national radio broadcasts. This less than whole-hearted initiative did not save his government and Mackenzie King's Liberals swept back into power, jettisoning most of Bennett's program in the process.22 One Conservative reform survived, however: the legislative package that became the Dominion Housing Act of 1935.

12 The Dominion Housing Act (DHA) was far from being a radical experiment in social engineering. In February of 1935 the Bennett government had struck an eighteen-member House of Commons special committee to determine if the public purse should be used to provide financial incentives for house building as a means of revitalizing employment in the construction industry. After receiving a favourable committee report, and following private discussions with the leaders of the Canadian mortgage industry, the final three-page act was drafted and duly passed. Patterned on similar New Deal legislation already in operation in the United States, the DHA aimed primarily at encouraging members of the middle class with secure sources of income to invest their money in building new houses.

13 This encouragement took the form of more liberal provisions for mortgages that reduced the required downpayment by supplementing the 60 percent mortgages available from private lenders with government-funded loans for a further 20 percent of the value, reducing the rate of interest to 5 percent, and lengthening the repayment period from the customary five years to a maximum of twenty. In effect, the DHA was a middle-class subsidy that did little to address the very real housing needs of low income Canadians.23 It did, however, encourage Canada's unemployed architects to participate in the 1936 home design competitions in the hopes that there would be a renewed demand for their services.

14 Although Eaton's competition was not directly linked to the new legislation, it was motivated by a similar desire to stimulate middle-class Canadians to invest in home ownership and, by extension, new home furmshings and appliances.24 An internal memo sent by the company's president, Robert Y. Eaton, outlined the anticipated benefits of the project:

Undeterred by the fact that the most tangible result of the 1930 competition was a model home that had proven disappointing as an in-store display setting, Eaton still believed that architectural competitions generated the right kind of publicity for the College Street store.26 He was hardly alone in his continued faith in this particular promotional device: American department stores and household goods manufacturers sponsored many such ideal home design competitions during the Depression.27 There were, however, significant differences between Eaton's conception of the 1936 event and its predecessor, the 1930 Ideal Ontario Home competition. This time designs for both small and medium houses would be requested. Also, instead of constructing an expensive and cumbersome reproduction of the first-placed design, the resulting competition entries would form the basis of an exhibition that could be circulated to various Eaton's stores across the country. In the case of the winning entries, the two-dimensional drawings would be supplemented by small maquettes.28

15 Direct inspiration for Eaton's competition came in part from the extremely well-publicized American competition sponsored by General Electric (G.E.) in 1935.29G.E.'s contest had also called for the design of a small and a mediumsized house, ostensibly in order to reflect the changing lifestyle of an imaginary middle-class client, the Bliss family. Generous prizes totalling $21 000 attracted over 2 000 entries which were then judged by a panel of experts that included not only architects but also builders, engineers, home economists and child framing specialists. The competition program emphasized that the goal of the designs was to ".. .bring about better health, increased comfort, greater convenience and improved facilities for home entertainment of the entire family," all of which, of course, would necessitate the extensive use of G.E. products.30

16 While managers certainly hoped to reap commercial benefits from a house design competition, Eaton's did not adopt G.E.'s strategy of overt self-promotion. Once the basic parameters had been set, the actual organization of the event was assigned to Orval D. Vaughan, the manager of the College Street home furnishings division. He was directed to consult with John M. Lyle, a leading Toronto architect, about the details of the competition program. Between them, Vaughan and Lyle developed the necessary design guidelines, which were published in dignified and impersonal language in the April 1936 issue of the R.A.LC. Journal.31 The program limited the size of the small house to 25 000 cubic feet (708 cubic metres). Within that space, competitors were asked to accommodate a living room, dining room or combined living and dining room, kitchen, four bedrooms, one bathroom, a recreation room and a one-car garage. Construction of such a house was budgeted at $7 500. The medium house, which was allotted 40 000 cubic feet (1 133 cubic metres) of space and a budget of $12 000, included such additional features as a pantry, a washroom, a maid's bedroom and bathroom, and a two-car garage. Although both houses were considerably less elaborate than the 1930 Ideal Ontario Home, even the scaled-down vision of suburban life that inspired the 1936 competition represented an unreachable fantasy for most Canadians during the Depression,32 It was obvious that the competitors' imaginary clients were solidly middle class; the sort of people, in fact, who might have money to spend at Eaton's.

17 As the competition was national in scope, entries were accepted from any registered architect in Canada and also from any graduate of recognized Canadian schools of architecture, which the program listed as the University of Toronto, McGill University, the University of Manitoba, the University of Alberta, the Ecole des beaux-arts of Montreal and the Ecole des beaux-arts of Quebec. Competitors were asked to submit a block plan with landscaping, complete floor plans, two elevations and a perspective drawing, all on a single illustration board 30 inches (76 centimetres) wide and 40 inches (102 centimetres) high. This system of presentation had been required for the G.E. competition and may well have been intended to facilitate the later exhibition of the drawings. All entries were to be anonymous and employees of the T. Eaton Company were not allowed to compete. Prizes of $1 000 each were to be awarded for the two best designs in both the small and the medium-sized category, while the five honourable mentions in each category would receive $500. In addition to the $1 000 first prize, a grand prize of $500 was offered for the best overall design. These were not inconsiderable sums at a time when the average annual Canadian income for a male wage-earner was $942 and many architects were unemployed.33 Hopes of winning elicited a total of 149 submissions prior to the competition's closing date of June 15,1936.

18 John Lyle not only played a critical role in developing the competition program for the T. Eaton Company, he was also invited to act as a judge and asked to select the two remaining members of the jury. He chose two fellow Toronto architects: Mackenzie Waters and Bruce H. Wright. Lyle's qualifications for the task were unquestionable. Rigorously trained in the Beaux Arts tradition, he had long been one of Canada's most respected architects and had received many important commissions.34 Less is known about Waters and Wright. Like Lyle, both were members of the so-called "Diet Kitchen Group," an informal assemblage of Toronto architects who were interested in fostering the connections between the decorative arts and architecture.35 The group's main activity appears to have been the organization of biannual exhibitions of architecture and the allied arts at the Art Gallery of Toronto. Waters also had a well-established practice, with a prosperous if unadventurous clientele, and had won several awards for his house designs. Illustrations of his work published in the R.A.LC. Journal indicate that he had a certain flair for the simplified Georgian architecture that was popular with monied Torontonians during this period.36 Wright, on the other hand, does not seem to have achieved the same level of recognition from his peers as his fellow judges; possibly he was a younger man who was only beginning to make a reputation. Interestingly, however, he did write a brief article on "The Modern Small House" which appeared in the April 1936 issue of the R.A.L.C. Journal.37 Based on the evidence of this article and a few published comments made by Waters and Lyle, it seems that the three men shared a guarded sympathy for design principles associated with the Modern movement.38

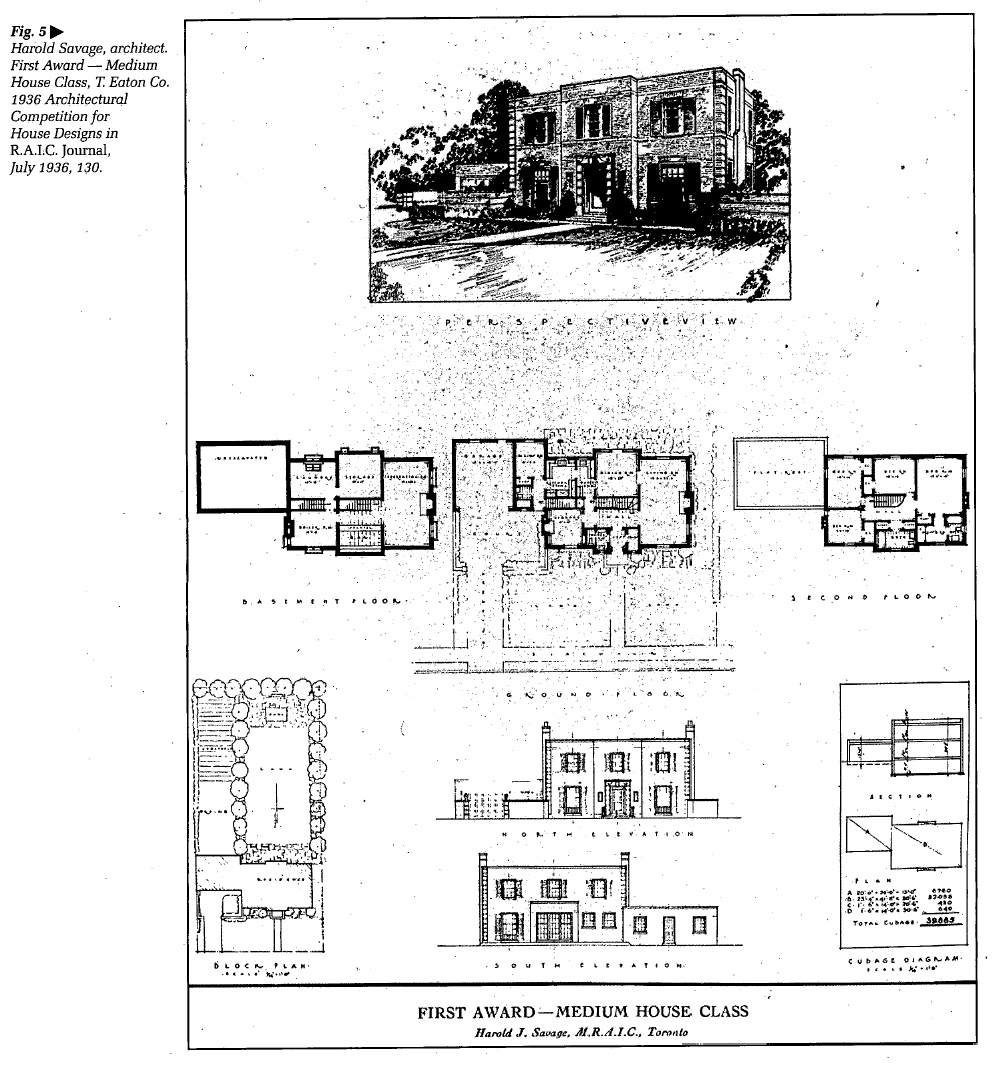

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 519 If anything, however, the panel displayed a residual bias towards the traditional in awarding one of the first prizes (Fig. 5) and an honourable mention to two relatively conventional designs in the medium-sized house category.39 Otherwise, the winning entries were representative of the overwhelming majority of the submissions in their use of a cubist design idiom inspired by European Modernism.40 The judges' surprise at this phenomenon was documented in their final report:

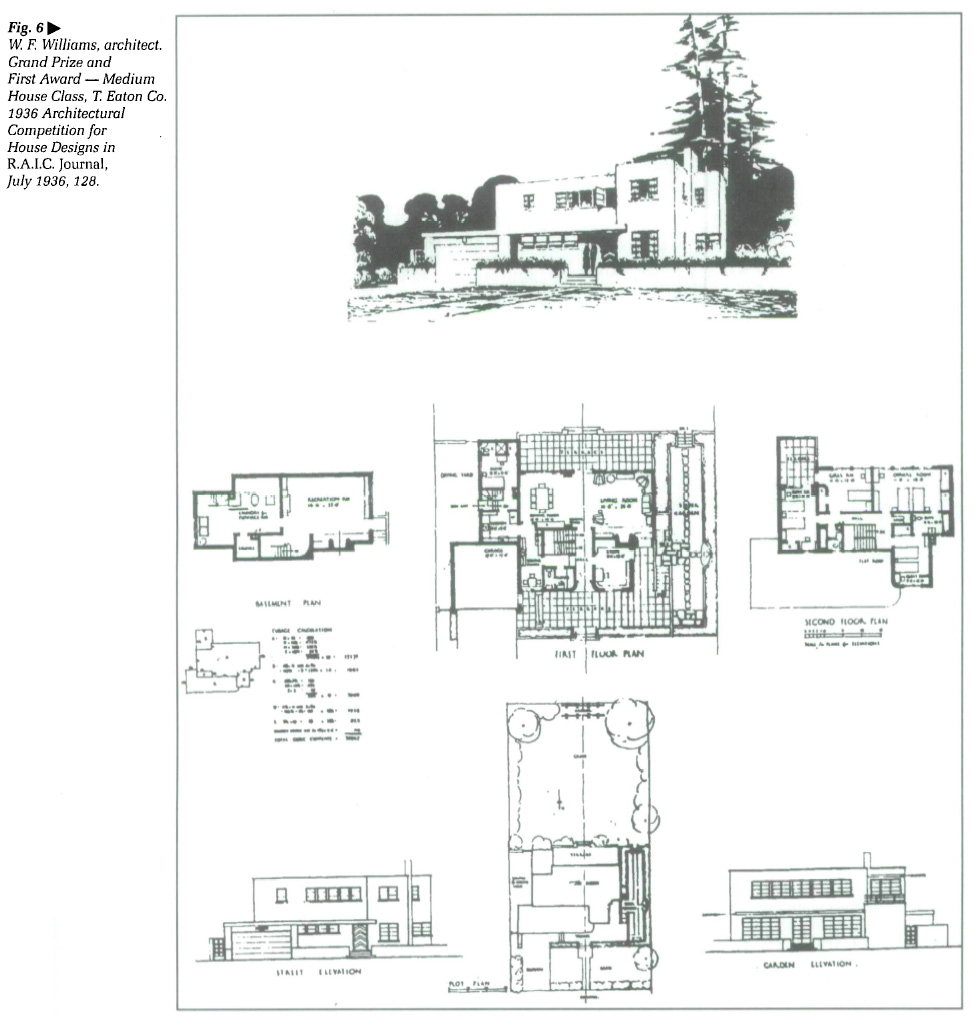

Competitors had been equally free in the 1930 Ideal Ontario Home competition, but with strikingly different results. The complete contrast between the 1930 and 1936 submissions is best illustrated by a quick glance at two designs by the same architect. In 1930 W. F. Williams had placed seventh with a design that married a two car garage with a gabled structure vaguely reminiscent of an Elizabethan manor house (Fig. 3). In 1936 he won the grand prize for a flat roofed, two-storey building with all the appearance of rigorous rationality that a strict reliance on straight horizontal and vertical lines could give (Fig. 6).42 A casual observer might logically conclude that the intervening six years between the two competitions had seen a revolution in Canadian domestic architecture.

20 In claiming that competitors were "free to adopt any style they wished" the judges spoke no more than the literal truth. No attempt had been made to dictate a particular approach to exterior treatment. On the other hand, very precise requirements had been laid out regarding features to be incorporated in the plan. As the judges noted, this specificity curtailed experimentation:

21 Arguably, restricting the competitors' options may have helped to channel their thinking into a particular design direction. They were expected to devise plans that satisfied a number of different functional needs associated with middle-class family life during the 1930s and that also conformed to relatively strict spatial limitations. Under such circumstances, the adoption of Modern "streamlined" strategies was hardly surprising. For example, the seemingly radical preference for flat roofs over the more conventional alternatives may well have reflected a desire to maximize the available space.44 Equally, space constraints would have made the small, efficient kitchens recommended by "modern" home economists and time management experts doubly attractive to the competitors.45 By stating that combined living and dining rooms would be acceptable, the program actively encouraged participants to consider this approach as an alternative to a more formal arrangement.46 An inherent bias towards this solution becomes apparent when the plan developed for the only traditional house among the first prize winners is considered. Harold Savage's decision to maintain the old division between living and dining room in his Georgian-inspired townhouse was criticized by the judges on the grounds that the dining room was too small (Fig. 5).47Clearly, while a formal layout was still possible within the parameters of the program, it was not as effective in its use of space as Modern informality. From the point of view of the competitors, therefore, a straightforward pragmatism may well explain some of the apparently Modern features shared in common by the plans for the majority of the prize-winning houses.48

22 By clothing their simplified plans in the Modern garb of wrap-around windows, seamless white walls and flat roofs, the competitors made a virtue of the necessities imposed by the program. The originality of their elevations and perspectives compensated for the sense of déjà vu engendered by the sameness of their interior layouts. Even here, however, most of the participating architects seem to have been working within well-defined, if unarticulated, parameters. While, as the judges commented, the exterior treatments were "more varied in character" than the plans, the variations were on standard themes that had been emblematic of European Modernism for at least a decade by 1936. Obedient to the axiom that the elevations should reflect function and plan, the competitors deployed cubist forms relieved by horizontal roof lines and banded windows to project an external image of the modern way of life to be found within the walls. Overall, however, their efforts were considered disappointing:

Both competitors and judges were dealing with a new set of rules; a slight sense of discomfort was perhaps to be expected. The jury's anxiety about the relations between mass, wall surface and fenestration betrays a certain unease about the Modernist habit of treating walls as the skin rather than the bones of the structure. Indeed, many of the entries, including the winner of the grand prize, exhibit an unimaginative stiffness in perspective that hints at the adoption of a mechanical convention, rather than a passionately-held creed (Fig. 6).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 623 One of the most interesting aspects of the 1936 competition program was the emphasis placed on the relationship between the house and its immediate environment. Participants were required to provide a block plan showing a landscaping scheme in addition to the plans, elevations and perspective that described the design of the actual house. As a group, the competitors proved to be remarkably consistent in the way they chose to orient their houses to the surrounding physical features of street and garden:

This rejection of the street met a similarly enthusiastic response from laymen, as shown by the comments published in Canadian Homes and Gardens concerning the winning entries in the government-sponsored Dominion Housing Act Small House Design competition, which also took place in 1936:

There is nothing radically modern in this inward-looking stress on the privacy of the nuclear family's backyard: the dream of comfortable seclusion from urban realities had been at the heart of the suburban ideal since the eighteenth century.

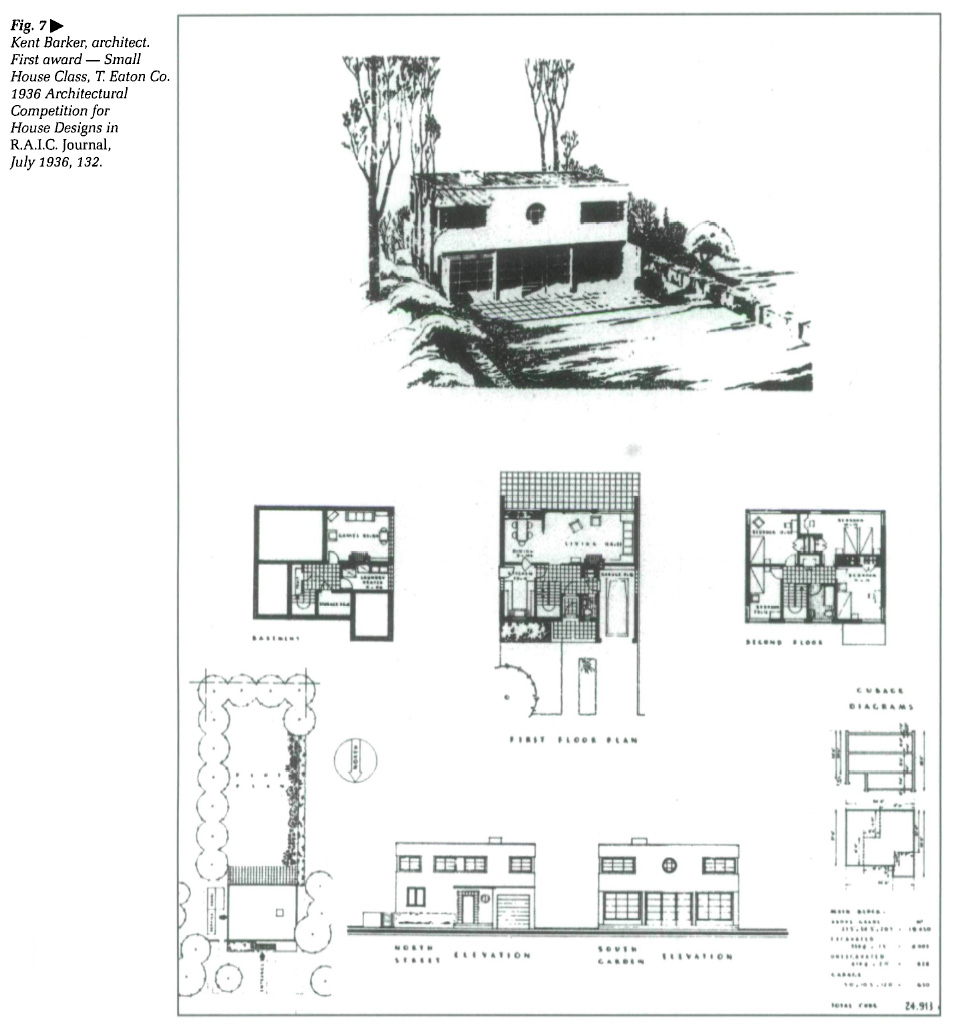

24 The concomitant attempt to minimize the physical distinction between the house and the natural world outside was, however, very much a part of Modernism's architectural agenda. Almost all of the houses designed for the 1936 Eaton's competition replaced the small windows typical of traditional dwellings with wide expanses of glass. This was taken to such an extreme in the case of Kent Barker's first prize winning small house that the jury gently advised modifying the design to make it more compatible with the rigors of the Canadian climate (Fig. 7).52 Various submissions went even further, incorporating the idea of the outdoor living room into the structure of the house in the shape of large balconies and, in one instance, roof gardens.53 Features such as these were among the recognized trademarks of European Modernism but they seem strangely out of place in the context of a Canadian backyard. As originally conceived, over-sized balconies and roof gardens were an effective response to a high-density urban environment where dwellings necessarily functioned as self-contained units. Transplanted to suburbia they lost much of their functional relevance and were transformed, ironically and inappropriately, into a species of applied decoration.

25 While the true nature and extent of the competitors' commitment to Modernism as an architectural creed are matters for debate, the fact remains that most of the entries were, to quote the jury, "in the modern manner." The demonstrated familiarity with the purely stylistic aspects of the movement is relatively easy to understand. Although it is impossible to determine how many of those involved in the 1936 Eaton's competition had viewed the work of the giants of European Modernism at first hand, by that time all would have had visual access to important examples of Modern design through books and professional journals.54 As the architect and critic Humphrey Carver pointed out in Canadian Forum, it was largely the existence of a growing body of literature on the subject that had made Modernism international:

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 726 Through publications and exhibitions such as the Museum of Modern Art's 1932 survey of the movement that introduced the term "international style" the fundamental principles of Modern design were gradually defined and codified. Thus, while some of those involved in Eaton's 1936 competition may have shared the reforming zeal of Modern architecture's leading proponents, others had simply learned the code.

27 Even this level of acceptance of Modernist design principle requires some explanation, as it suggests that there had been a marked change in attitude within the ranks of Canadian architects since 1930, when Philip Turner, one of the judges in the Ideal Ontario Home competition, coolly dismissed Bruno Taut's case for the Modern approach to domestic architecture with the following words:

Traces of a hesitant evolution in opinion can be found in articles published between 1930 and 1936 in the R.A.I.C. Journal. During the late 1920s, Canadian architects and architectural critics were reluctant to accept the European avant garde's definition of Modern architecture, with its deliberately revolutionary overtones. Instead, like many of their British and American counterparts, they were far more likely to advocate the combination of modern technological improvements with traditional building styles.57 A few years later, however, complete dismissal of European Modernism had given way to a certain curiosity about the movement.58 This interest seemed to gain in momentum as Modernism achieved greater acceptance in Great Britian. Articles about the lively debate between traditionalists and modernists in the mother country were reprinted in the R.A.I.C Journal.59 Even more significantly, Modern buildings, including cubist houses, began to be illustrated in its pages.60 The first phase of outraged rejection was clearly over; instead a compromise position that sought to incorporate the worthwhile aspects of Modernism into the existing body of architectural tradition was advocated:

Canadian architects during this transitional period often reduced Modernism to a list of isolated attributes from which they were then free to pick and choose according to the needs of the moment. For many of the participants in the Eaton's competition the "modern manner" was probably precisely that: a set of useful conventions that could be applied to produce a house in a newly-fashionable style.62

28 This is certainly the approach adopted in an attempt to market the services of the architect as an expert on the "modern manner" to the potential clients that subscribed to decorating magazines. By 1936 the Toronto branch of the Ontario Association of Architects believed that this relatively well-to-do subgroup was sufficiently interested in Modern domestic architecture to warrant the insertion of the following advertisement in Canadian Homes and Gardens:

The deliberately anonymous advertisement went on to assure would-be home owners in pursuit of all the latest modern features that "Your architect can satisfy you upon all these and other points involved in planning and building a house."

29 This discrete promotional device was an artifact of the Depression. In their eagerness for new business, the architects responsible for the advertisement sought to persuade prospective clients that their professional guidance was required to negotiate the unfamiliar maze of Modernism. The Modern entries in the 1936 house competitions, which clearly demonstrated familiarity with the new style, can also be seen as part ofthis marketing strategy. Similar claims of exclusive aesthetic expertise had been advanced throughout the nineteenth century by North American architects competing with speculative builders for recognition as the ultimate authorities on questions of domestic design.64 In the 1930s, architects staking out the Modern house as their particular territory were unlikely to face much competition from their traditional rivals for the middle-class market: speculative builders were interested in saleability, not innovative design.65 With luck, however, there might be individual clients with sufficiently advanced tastes to commission such houses. A reassuring tone of practicality pervades the advertising copy, suggesting that architects were equally adept at producing avant garde designs and making sure that the resulting dwelling would have an adequate number of closets. After all, Modern styling had proven to be a compelling selling point for other consumer durables — why not for houses?

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 830 Eaton's had certainly demonstrated its faith in the commercial potential of Modern design, and a consciousness of the store's sympathy towards innovation may also have had a certain influence on the competition entries. Toronto architects at least would have been well aware of Eaton's ground-breaking attempts to market art deco and moderne furniture even before the opening of the College Street store. In 1928, the store had taken the ambitious step of hiring a French designer, René Cera, to establish an "Art Moderne" department.66 He was expected to design furniture and interiors for individual clients and to consult on the store's purchases of manufactured house furnishings in the Modern style. The experiment proved to be a financial failure, and the specialized department was closed down in 1930.67 Nevertheless, Eaton's continued to promote Modern design actively throughout the 1930s.68 This policy may well have originated at the top, as it appears that the company president, Robert Y. Eaton, was an early convert to art deco. He was so enthusiastic, in fact, that he recommended that members of Eaton's decorating staff travelling to Europe should go on the Ile de France as a means of learning the new design principles through direct experience.69 A younger member of the family, John David Eaton, displayed his own openness to new design developments by commissioning Toronto architect H. J. Burden to create a Modern house for him in the wealthy suburb of Forest Hill (built 1937-39).70

31 The Eaton competition judges had their own theory about the surprising predominance of Modern designs:

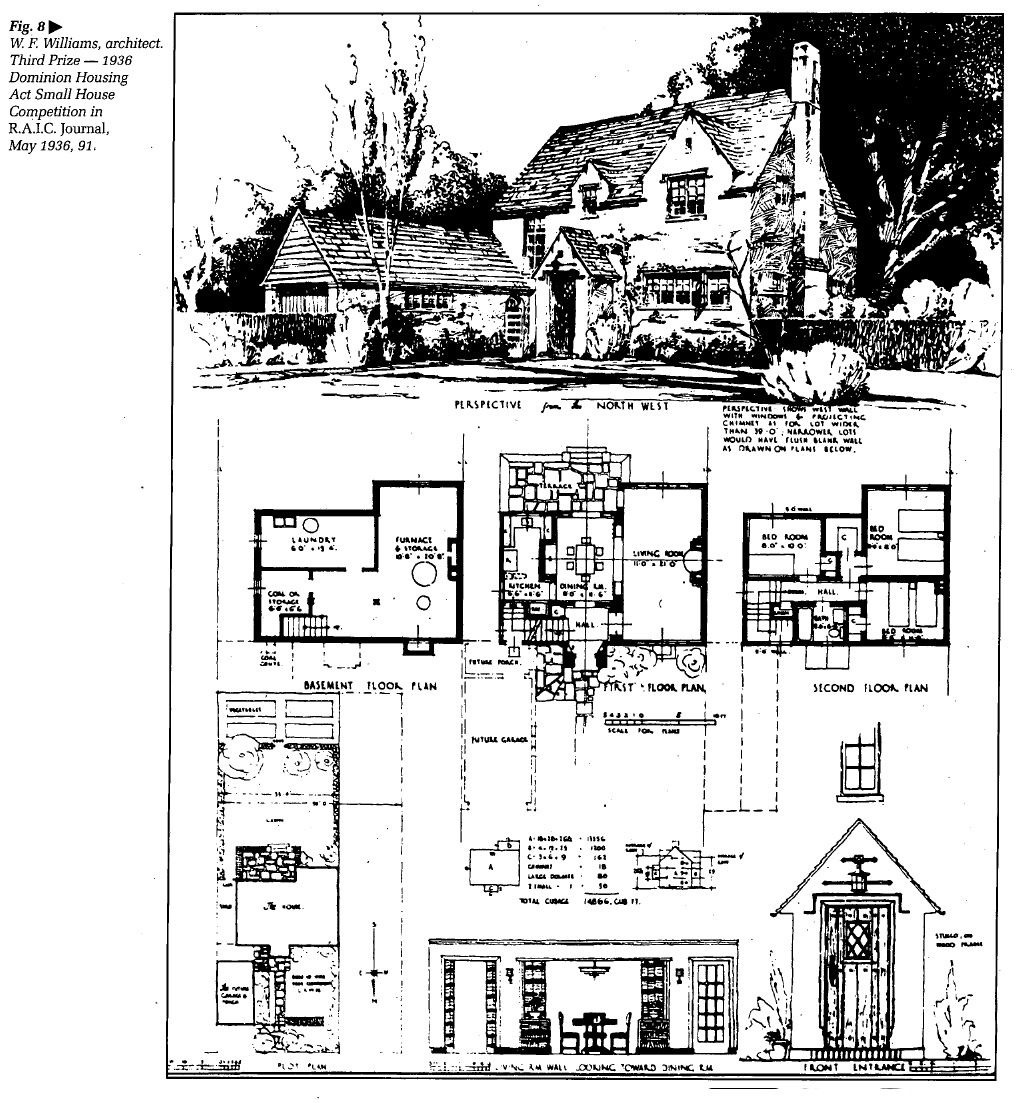

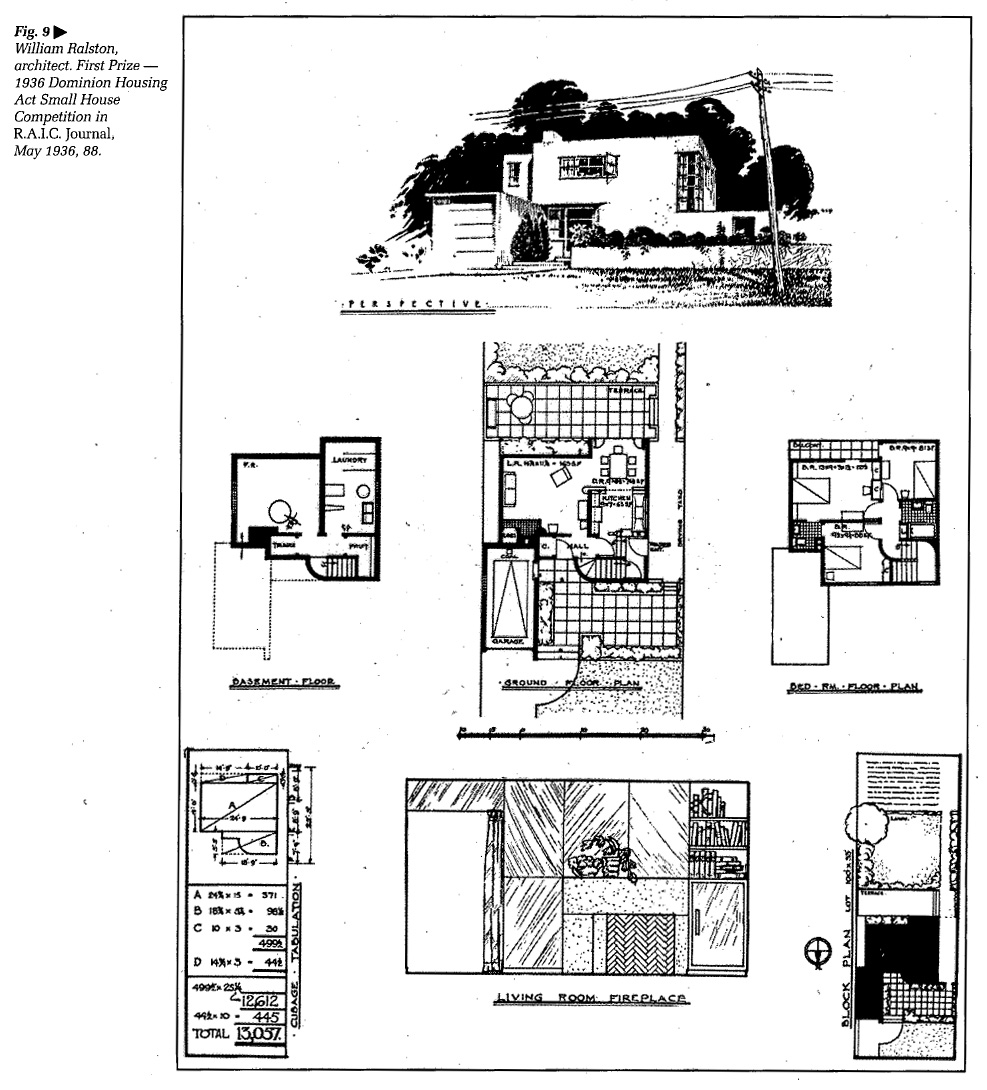

For example, the folio of prize-winning entries for the G.E. competition published in the April 1935 issue of Architectural Forum indicates a bias towards approaches influenced by European Modernism, even though it was equally possible to design a house in a traditional style that would meet the competition objectives. Those Canadian architects who had unaccountably missed the public relations hoopla surrounding the G.E. contest could learn their lesson by observing events closer to home. The April 1936 issue of trie R.A.I.C. Journal that contained the program for the Eaton's competition also included illustrations of the winning designs in the federal government's Dominion Housing Act Small House Competition. While W. F. Williams was awarded third prize for a scaled-down version of his 1930 design (Fig. 8), William Ralston's distinctively modern entry placed first (Fig. 9).72 The experience had an obvious impact on Williams's submission to the Eaton's jury two months later, and he was probably not alone. Whether or not Canadian architects had fully accepted Modern design principles, they correctly concluded that Modernism'had the charm of novelty required to win competitions in 1936.73

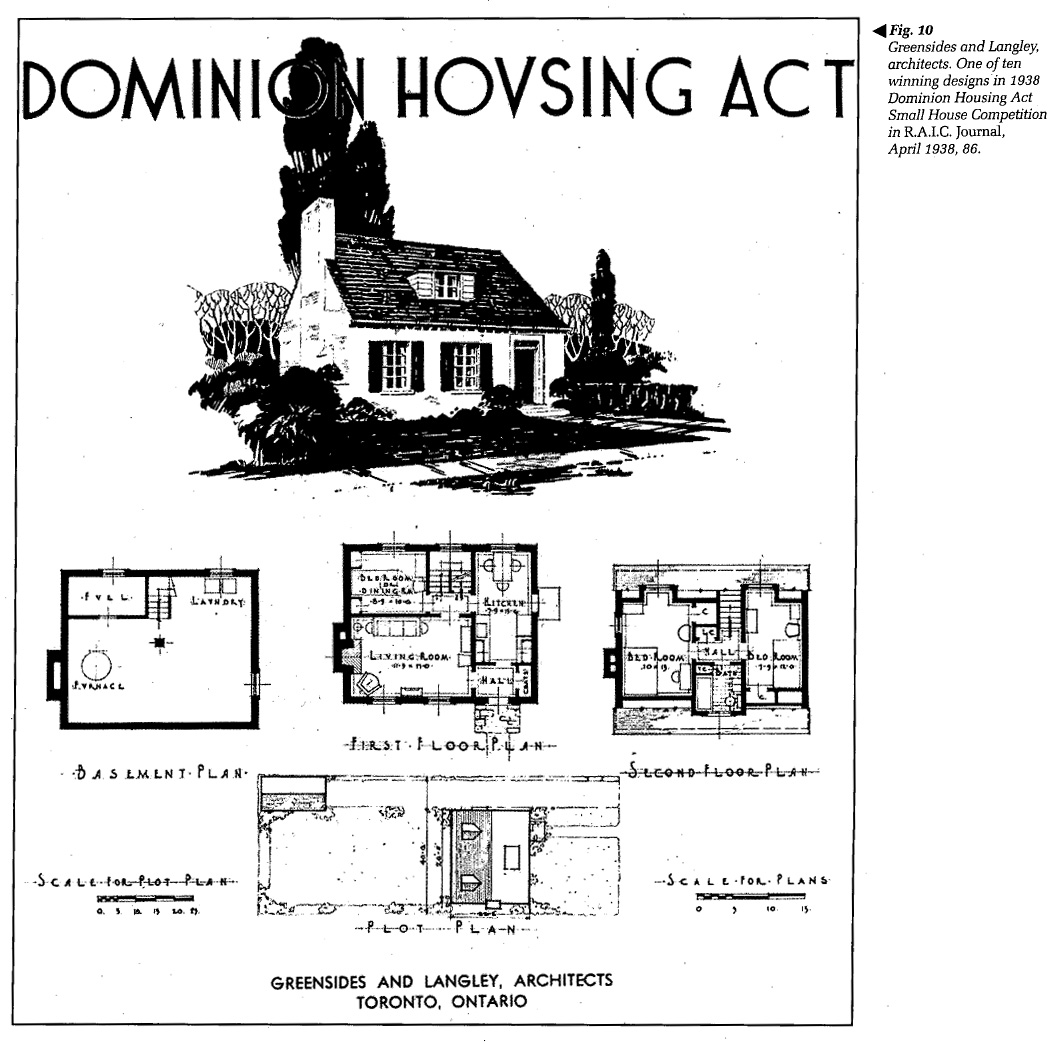

32 It was a charm that wore off fairly quickly. A mere two years later, in 1938, the majority of the winning designs in a second small house competition sponsored by the federal government were once again inspired by traditional models of domestic architecture (Fig. 10). Commenting on the discrepancy between the 1936 and 1938 competitions, A. S. Mathers noted the revealing fact that very few of the 1936 houses had ever been built:

The embarrassing history of the attempt to construct a prototype of W. F. Williams's grand prize winning design in suburban Toronto bears out the second half of Mathers's criticism. Eaton's decided to abandon the project when tenders based on working drawings and specifications prepared by Lyle and Williams came in at twice the cost originally budgeted in the competition program.75

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1033 In the final analysis, however, Mathers's first point may be even more telling. The standard objection that "She just don't look like a house" quoted in Bruce Wright's 1936 article on Modern domestic architecture may well have been raised by middle-class home builders and mortgage companies alike, thus combining aesthetic preferences and economics in a powerful case against Modern architecture.76 Even Humphrey Carver, one of Modernism's most committed and vocal supporters, had his doubts about introducing such very different houses into Canada's residential streetscapes:

Carver was perfectly correct in arguing that the designs generated by the 1936 Eaton's competition would have been out of place in a suburban setting, although he showed his own Modernist biases in singling out their individualism as the source of their essential incompatibility. The ideas and alternatives proposed by the competition were rejected for the most part by the few Canadians in a position to build a home during the Depression for quite different reasons. Arguably the white cubist forms associated with Modern domestic architecture in the interwar years were incompatible with the ethos that informed the middle-class suburbs of North America. The suburb placed a psychological, and physical distance between the urban work place and the home. Houses modelled on the clean lines of twentieth-century industrial buildings had no place there.78 A Modernist idiom that was more sensitive to its surroundings would have to be developed before such houses could become popular alternatives to more traditional dwellings.

34 The three ideal house competitions held in Canada in 1936 gave Canadian architects a welcome opportunity to promote themselves to an important group of potential clients: middle-class home owners. The Eaton's competition was especially attractive because events sponsored by the store reached a wide audience of consumers. Interestingly, the architects used this opportunity to experiment with Modern house designs. While their motives for doing so may have been mixed, the designs they produced demonstrate that a significant number of Canadian architects had achieved a fair level of familiarity with the tenets of European Modernism. In turn, Eaton's use of the competition for publicity purposes increased public awareness of contemporary architectural developments. Awareness would develop into acceptance in the years following World War II.