Articles

Transforming the Food Axis:

Houses, Tools, Modes of Analysis

Abstract

The open-plan house has usually been explained as the result of architects' modernist aesthetic aims. In the early twentieth century these flowing spaces that housed reception and social functions excluded the kitchen. However, in both popular and architect-designed houses after World War II, a kitchen was often opened up to the other social spaces in the house. What caused this shift along the food axis (food preparation, storage, and service spaces) from closed and service-oriented to open and sociable? The changing role of women and a changing household economy explains the spatial redefinition of the kitchen, and suggests some new methods for the analysis of domestic space.

Résumé

L'avènement de la maison à aires ouvertes est habituellement perçu comme l'aboutissement des visées esthétiques des architectes contemporains. Au début du XXe siècle, les vastes espaces qui répondaient aux fonctions sociales et aux réceptions excluaient la cuisine. Néanmoins, dans les habitations populaires et les demeures dessinées par les architectes après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, la cuisine s'est souvent ouverte aux autres espaces sociaux. À quoi doit-on ce déplacement de l'axe de l'alimentation (préparation de la nourriture, entreposage et aires de service), c'est-à-dire des espaces clos, purement fonctionnels, vers des aires ouvertes, conviviales? Le rôle nouveau des femmes et l'évolution de l'économie ménagère expliquent la redéfinition spatiale de la cuisine et suggèrent quelques méthodes inédites pour l'analyse de l'espace domestique.

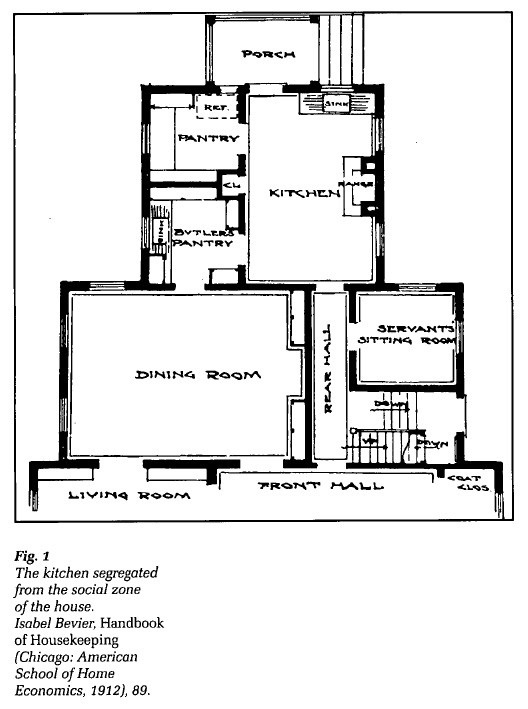

1 Over the last 150 years the accepted relationship of kitchen, food storage, and dining spaces — what might usefully be termed the food axis of the house — has undergone significant transformation. In the era between the Civil War and World War I, the kitchen-and-service zone of an American middle-class house had opposing sets of attributes. A beneficiary of new technologies, the food preparation zone was more convenient than any in the past; but it was also seen as the source of obnoxious smells and germs. House-owners knew the kitchen as the place where women (servants or housewives themselves) worked; separated from the rest of the house, it was a place that their friends would never see. To protect both guests and residents a good house plan would spatially segregate the kitchen-and-service zone from the social spaces1 (Fig. 1).

2 By the mid nineteenth century, middle-class urban and suburban houses were conceived according to zones of use: the social zone was for the reception of guests and family sociability, the service zone for household work and servants, and the private zone for sleeping and private family activities. Cooking in the nineteenth century house belonged firmly in the service zone while serving meals was a social activity and the dining room was one of the reception rooms.

3 Special dining rooms were set aside for eating the foods that issued from the preparation zone, presided over by the mistress of the household. These were decorated with specialized furniture designed for serving meals to guests and family in a space segregated from the food's preparation. China and linens could be stored in the dining room but not foodstuffs. In the confines of the dining room, both men and women encountered food, while in the kitchen it was principally women who engaged in its preparation.

Display large image of Figure 1

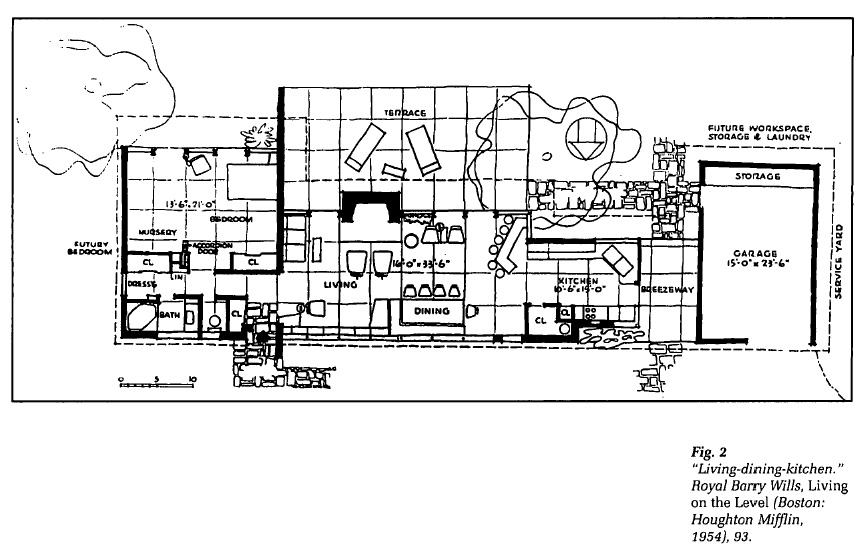

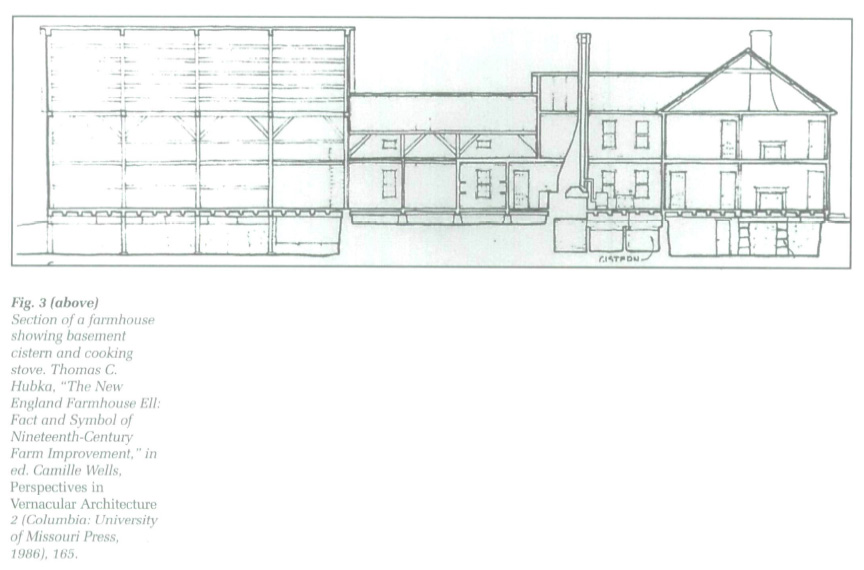

Display large image of Figure 14 Yet by the post-World War II era, dining rooms had become relics of an old-fashioned way of life, and the kitchen had expanded to include socializing. The 1950s kitchen had become a kind of family living room, from which Mother managed the whole household. Open planning allowed the kitchen manager to have a view of adjacent social spaces in order to participate in the social life of the house. The smells of cooking that emerged from this kitchen were interpreted as alluring invitations to come and eat delicious things — either in the kitchen, or at a table set up at the end of the living room and open to the kitchen. Not just family members, but even guests were to be invited into the kitchen to sip cocktails and select canapes from the formica kitchen island2 (Fig. 2).

5 Traditional histories of architecture observe that this "open plan" is characteristic of modern architecture, and trace the breaking down of walls, the development of "flowing space," to origins in the 1870s Shingle Style through Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie style, to 1940s modernists. However, while the usual history of the open plan accounts for the opening up of reception rooms and stair halls to each other, it cannot account for the transformation of the kitchen into social space. I will trace how this transformation from hidden to open, from servant-oriented to sociable, came about, proposing that an open plan that includes the kitchen can be attributed more to changes in household economy and women's roles than to the aesthetic ideals of modern architects.

6 The breakdown of the boundaries between reception and service zones and the architectural changes that follow are best revealed if we shift our attention to activities rather than rooms, a perspective that can give us new insights into the history of domestic architecture. Such "activity arenas" — systems of tasks and spaces — relocate the architectural historian's object of analysis from the contained spaces that the built object delivers, to the spaces-in-action that users create. I will be considering the system of tasks and spaces that make up the food/eating axis of household activity. This conceptual axis, spatialized in the architecture of the house, includes spaces for food preparation and cooking, serving and feeding, storage, and disposal. But it is not adequately enclosed by the familiar architectural labels "kitchen" and "dining room." I want to emphasize the three-dimensionality of this activity arena, and show how it escapes from the confines of the house plan into section, site plan, and neighborhood map. Then I add to the usual functional considerations of space, the question of who uses spaces (a "who" who has both gender and class) as one determinant of house design.

7 One reason to focus on activity axes is that the link of a function to a particular room is historically unstable. If we look at where people have prepared and eaten their meals over time, we find these activities migrating through the house according to time period, class and region. Cooking food requires a heat source, but that may be located in an open fireplace or in a range or stove. The cooking site might be in the hall fireplace of a colonial New England house or in the patio of a California adobe, in the iron cookstove in a nineteenth-century brownstone basement or a farmhouse ell.3 In the eighteenth-century American south, the cooking commonly moved from the basement in winter to a rear outbuilding in summer. A different domestic space unfolds when we see it through the lens of the activities of food preparation and service rather than through the labels on a plan.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 The same migration is found in dining as a household activity. Meals were served to family and guests in the several rooms of seventeenth and eighteenth century houses including chambers where sleeping, storage and other functions were also accommodated. Dining came to roost in the "dining room" during the nineteenth century, then moved on to eat-in kitchens, to dining areas within living rooms, to family rooms and elsewhere. In the post-World War II era the kitchen absorbed the dining activity and even part of the living room's social functions. Once aware of these migrations, architectural historians can question the boundaries and designations of a "kitchen" or "dining room" instead of taking them for granted.4

9 Keeping these issues in mind, let us look at the 1860s service end of the house. The middle-class house of this era would have had several rooms with quite specific and differentiated functions assigned to them. One of them was a room called the kitchen, located at the back for freestanding houses in suburbs and farms, in the basement of some city houses, or in a detached outbuilding in parts of the south. Some houses had a front and a back kitchen; some had an indoor and a detached kitchen. The room called "kitchen" was supplemented by several other spaces in cellars, attics, and yards critical to food storage, preservation and preparation.

10 A cool room in the cellar, an icehouse in the rear yard, a spring house over running water, or an ice-box in a cellar or rear entryway, were the ways of keeping foods cool in that era. Since these did not always hold a consistent temperature, food spoilage was common. Advice books instructed kitchen managers on how to clean the ice-box well enough to get rid of odours; the author of the 1884 Anna Maria's Housekeeping believed that the "unsatisfactory odors about ice-box and meat safe" come out in headaches, sore throats and fevers that "haunt the house." Beecher and Stowe recommend an ice-closet in the basement of the house design published in their 1869 book American Woman's Home; it was described as a tin-lined wooden box with a drain on the bottom and movable shelves.5 Additional cool spaces for food storage were to be found in both rural and urban backyards and cellars at mid century.

11 These supplemental spaces remind architectural historians that a particular activity needs to be tracked in both plan and section: the analysis of domestic architecture requires a three-dimensional awareness. Food storage requires all kinds of subsidiary spaces that can keep materials cool or dry or clean, and before World War II these were normally outside the cooking room. Exterior buildings on a farm-stead or in a city kept milk cool or housed the smoking of meats. Cellars contained storage rooms designed to stay cool and to protect foods from rodents; dried food and herbs were stored in the attic. Coal and wood to fuel the cookstove was stored in cellars or rear sheds. Rather than a single kitchen room, then, food preparation implies a network of spaces above and below ground, both attached to the house and separated from it. Thus, just an analysis of house plans will not be adequate; we will need site plans showing outbuildings and sections letting us see related activities above and below the kitchen level (Fig. 3).

Display large image of Figure 3

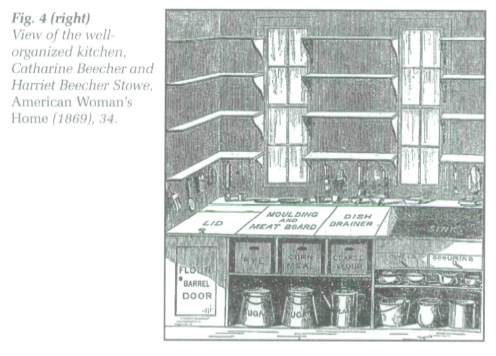

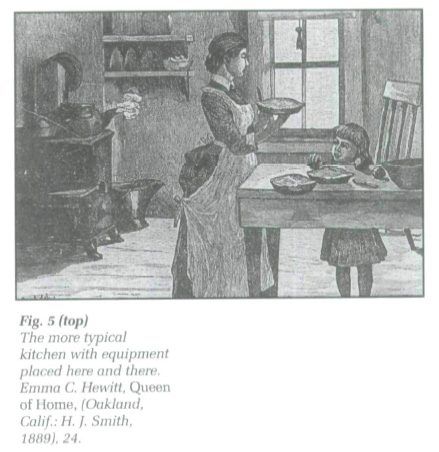

Display large image of Figure 312 What was food-preparation equipment like in the mid-century kitchen? The standard kitchen appliances in a mid nineteenth-century middle-class household comprised a range and flue on one side of the room and a sink on the other. Food preparation in the 1860s benefitted from inexpensive iron ranges or cooking stoves, run on coal or wood.6 From the 1840s onward, the cooking range might also hold a boiler for hot water. Hot water for bathing thus came from the kitchen, and non-fixed bathtubs were used in several rooms including the kitchen.7 Kitchen gadgets such as apple peelers and corers, potato peelers, and egg beaters were available at low prices to make kitchen labour more specialized, if not easier. Indoor plumbing was available for kitchen sinks, and water might be delivered by a hand pump, a cistern or city-supplied water depending on the resources of the household and whether the house was in an urban or rural setting. Although Beecher and Stowe had illustrated a rationalized kitchen with a continuous work surface and everything stored in specialized cabinets, views of contemporary kitchens show none of their systematization. Instead, the typical kitchen had a few separate and discontinuous items ranged around the walls, and perhaps a center work table (Figs. 4 and 5).

13 Account books kept by the Roberts family, who lived near Philadelphia, give us a glimpse of a farm household's attention to the kitchen and its equipment. Records show them adding on a new kitchen in 1850, buying a new cook-stove in 1852 and a second one in 1859, purchasing a washing machine in 1859 and a wringer in 1862. Until 1870 the Roberts account books show that they baked their own bread in the kitchen, but then began to buy it from a baker.8

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 414 Production outside the house contributed to a more spatially compact service zone in the mid-century house. In the case of bread production, eighteenth-century households had made their own. The earliest baking ovens had been located out of doors in free-standing beehive-shaped brick structures, still in use into the nineteenth century in many regions of the United States. Hollowed-out brick ovens were also built into the sides of early hall or kitchen fireplaces, which Anglo settlers used to bake bread and cakes and to roast grain. The new cookstoves of the mid-nineteenth century had interior chambers for baking, which replaced earlier bake ovens. But for many householders, the town baker produced bread, and purchasing a loaf was preferable to making one's own.

15 Proximity to a professional baker, then, meant that the bread oven was no longer needed in the private house, and the service end of the house could shrink accordingly. The newly efficient stoves and sinks in the service end of the modern house are therefore caught up in the relations of a household to the outside world. In the second half of the nineteenth century grocery stores proliferated, stocking canned, boxed and other prepared foods on their shelves. Kitchens that no longer had to house butter and soap making or bread baking became smaller. External services and products, especially available in cities, satisfied some of the needs the kitchen once served. Thus the reason that a certain era's food preparation zone took the form it did must in part be explained by what was happening on main street.9

16 The middle-class mistress of the household stayed at home in her "separate sphere" to raise her family, and to execute and oversee the housework in the 1860s and 1870s. Household advice books such as Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe's or Marian Harland's assumed that the reader/housekeeper had a servant to help execute the housework instructions. The Roberts family account books show that they always had servants — one or two who lived in, some who came for weekly washing and ironing, and some occasional help such as the seamstress who stayed from eight to twenty weeks during the year. Servants in eighteenth-century households, often the children of relatives or neighbours, had taken meals with the family. However, by the mid nineteenth century servants increasingly were immigrant labour, less welcome to be treated like family members. So the service side of the house became more architecturally separate, more isolated from the family's reception rooms and private quarters.

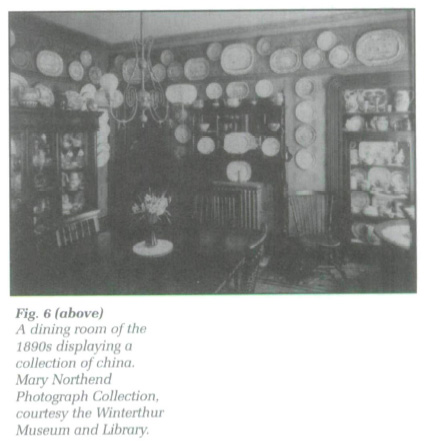

17 Specialized dining rooms of the mid nineteenth century received much more attention as to form and decoration than meir companion kitchens did.10 Architectural plan books aimed at all levels of the middle class, published in large numbers from ca 1850 on, preserve advice about dining room size and location in houses. As historian Clifford Clark has pointed out, Andrew Jackson Downing, in his Architecture of Country Houses, recommended different types of houses suited to different income levels.11 Farm houses and cottages for mechanics and working men lacked dining rooms; only the villa for people of "taste and elegance" had its own dining room (Fig. 6).

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 618 Dining room furniture came on the market in the ante-bellum period in suites of preselected pieces — a table and chairs for the center of the room, a sideboard and a china closet for the periphery. As meals and the furnishings to support dining grew in elaboration, dining in other rooms of the house seemed ungenteel. Yet because the dining room was only used two or three hours out of a day, it came in for criticism as "wasted" space. Some contemporaries also saw as ungenteel using the dining room itself for unrelated activities, but architect Henry Hudson Holly recommended in 1863 that the family could use the dining room as a sitting room, since the servants work was removed to concealed areas beyond the dining room door. Do not consider the dining room just a '"general utility' room," urged a writer for The Decorator and Furnisher in 1896; it should serve as a garnering spot for family and friends, do double duty as a sewing or sitting room, and be decorated in a cheerful and attractive way, "restful and nerve-soothing." Because of its spatial situation as the link between the reception rooms and the hidden kitchen spaces, the dining room was also always a key circulation space.

Display large image of Figure 7

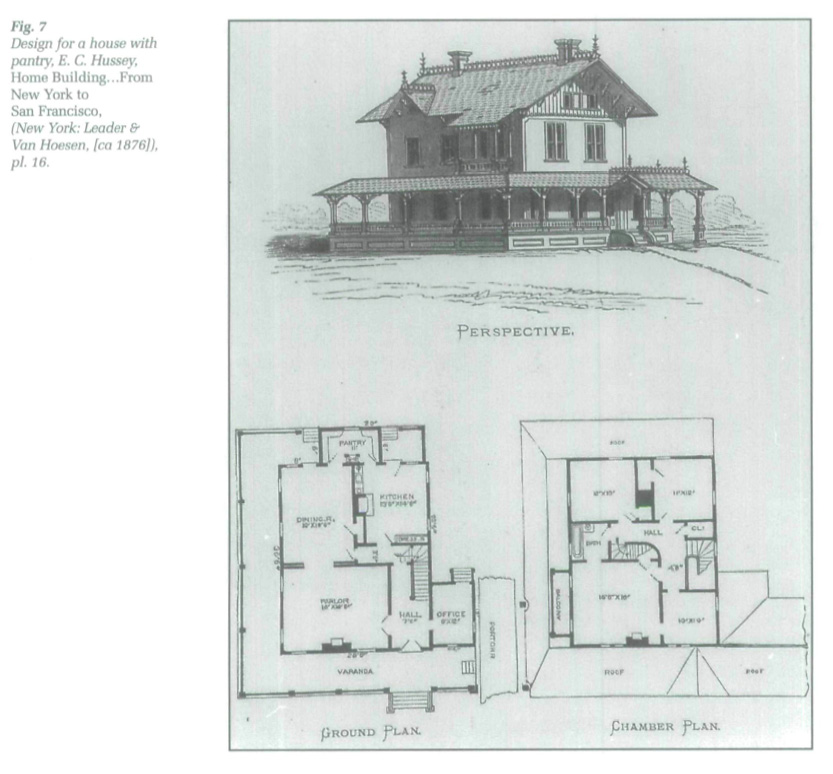

Display large image of Figure 719 By the 1870s, plan books for middle-class clients show the inclusion of a butler's pantry, a room for servants' work that linked the dining room with the kitchen. The butler's pantry was "a valve controlling the flow of traffic," the smells, and the sounds of kitchen labour to protect the dining room.12 Servants were crucial in the structure of a nineteenth-century middle-class household, but they were felt to be most desirable when least visible. Servants had their own staircases and hallways whenever the extra space could be afforded, so they could execute the work of the household without being seen. The butler's pantry provided a buffer zone between the servants production in the kitchen and the masters' consumption at the table13 (Fig. 7).

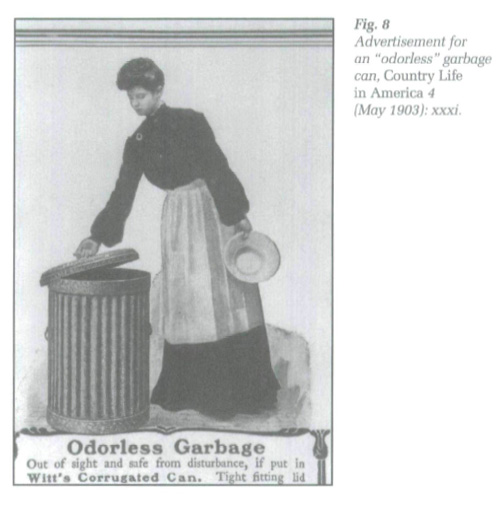

20 Likewise the dining room functioned as a buffer between two worlds: that of genteel sociability in the parlour — now a purely social room — and that of dirty kitchen labour. When we turn to the meanings attached to kitchen and dining architecture, this food/ eating axis spans between two extremes of "dirt" and "not dirt," defining "dirt" in the way identified by anthropologist Mary Douglas as "matter out of place."14 Food preparation, cooking and the disposal of wastes is a dirty business. It makes a mess that continually needs to be cleaned up. Odours arise as foods spoil if they get too warm or too old. Cooking itself gives rise to smells. Dining, however, represents the clean pole: fresh table cloths, china, neatly contained foods ready to savour, good smells. A vocabulary of odours recurs in descriptions of and prescriptions for houses, calling our attention to the polarized nature of the food preparation and service zone. Dining rooms had to act as the separator of conceptually clean social spaces and conceptually dirty food preparation and servants' spaces (Fig. 8). The Victorian dining room also acted as a mask for the work of food preparation. The dining room, seen earlier as a spatial buffer between areas of the house, becomes more vivid as a room designed to conceal housework in general and specifically the work of the wife/housekeeper serenely seated at the head of her table.

21 In the North American house of this era, cooking was typically seen as women's work, and female servants along with the housewife, or the housewife alone, did the work in most households. Anthropologist Jack Goody reminds us that who cooks — men or women — varies by culture. In Europe, women cooked at home while men cooked professionally; the same in ancient Greece. In Africa, women cook both at home and professionally.15 In this American history, the housewife is a central figure in both the clean and the dirty poles of the food axis; she is both mistress and servant, both producer and consumer in the food system, she manages both the overt and the covert spaces of the house.16

22 This conflicted position of the housewife was made obvious by the spatial configuration of the 1860s house. The housewife would work over the sink and stove with her servants; then she would put on her dinner dress and entertain her guests at the dining room table. The segregation of clean and dirty poles effected by the architecture supported her two divergent roles in the house. But her double position would be obscured by the new architectural forms of the post World War II era.

23 In the later nineteenth-century house, then, the food-service axis comprised an active array of food preparation and storage spaces both within and outside the house, which was populated by the women of the household, both family members and servants. This zone was buffered from the genteel dining room with its cleanliness and decorum, rituals of properly served meals on schedule, guests entertained. The segregation between the service and social zones was as complete as possible.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 824 The modern attitude that surfaced with the new twentieth century valued efficiency in the organization of the house, freeing women to become more active in mothering and in public pursuits. The "new woman" was to join clubs, do good in the community, and develop a life beyond the home. In this era's modern house, elements of the kitchen are newly represented as a "system" — a system of food intake, preparation, service, storage, and cleaning up. Everything necessary for these related functions was to be contained in an interconnected sequence of kitchen, pantries, cold-room in the basement, ice-box, back entry and service porch. The foods and work in dispersed spring houses, smokehouses or attics — elements of the mid nineteenth-century service zone — were pulled closer together in space, and made smaller for a more economical use of space in the turn-of-the-century service zone. This sequence was then linked to the dining room. Smaller houses might have fewer such individuated spaces, but the system concept remained the same.17

25 In collapsing the food/eating axis spatially, early twentieth-century house builders drew the old functions into the house. The once dispersed icehouse, spring-house, smokehouse, attic, cellar, and well became the new generation's refrigerator, storage cabinet, and indoor plumbing. Architectural units were reinterpreted as appliances, and the dispersed spatial structure that required many people's labour was collapsed to be workable by a single person.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 926 The generation of commentators active in the early twentieth century characterized the new kitchen using production metaphors. As a writer of 1905 expressed it (twenty years before LeCorbusier): "the whole thing should be a machine, whose working parts are perfect." For another in 1913, the kitchen was characterized as "workroom where much precise measuring and careful cleansing must be done."18 A 1922 author called hers "a cooking laboratory," giving a scientific flavor to the kitchen19 (Fig. 9). This science-like language parallels the rise of home economics as a discipline that applied efficency theories ("Taylorism"), first seen in industrial production, to the work of the household. Some authorities even recommended special dress — housekeeping uniforms for the professionalization of housework.

27 The kitchen, now conceived as a pure and rationalized workroom, was best if it was as small as possible. The happiest cook is the one who can stand in the centre of her kitchen and reach all her appliances and equipment, asserted a 1903 Country Life in America.20 An ideal kitchen would allow the cook to be able to perform all duties by simply "revolving" in the center of the room. The beginnings of ergonomics can be seen in this 1905 observation: the cook "stands in certain places and uses certain things which should govern the arrangement" of a kitchen.21 Careful planning of the kitchen will eliminate "futile effort in walking and unnecessary gymnastics in gathering utensils and materials for cooking."22 A 1913 author stressed the new purity of purpose for the kitchen: "To use the kitchen simply as a cook room and scullery, a place where food is prepared and pots and kettles are scoured, is the modern aim. All tramping through the room by service men or family is avoided."23

28 The 1910s saw the triumph of functionalist thinking in organizing food preparation spaces and activities, realizing Beecher and Stowe's projections of forty years earlier.24 The built-in cabinets recommended by a 1913 writer for cooking tools should have just the right amount of space for the kitchen inventory. Hooks for saucepans and spoons, special close shelf-spacing for platters and for cups, grooves for kettle covers, allow kitchen equipment to be stored "like a tool on a tool rack." Electricity brought better illumination to the kitchen as well as small motors that could power household machines. An illustration in The House Beautiful of 1920 showed a kitchen with "a 'kitchen-aid' motor, for mixing, grinding, etc.," a second mixing machine, an electric dishwasher and a refrigerator.25

29 The kitchen entry is the place for "systematizing the business of housekeeping" by providing a focal point for all services, wrote House and Garden contributor Verna Salomonsky in 1922. She envisioned this entry space as the center of communications: goods are received from delivery men, trash goes out; the servant's stair to the upper floors links up here. A rear porch provides an outdoor workroom; an underground garbage can is accessed through a trap-door in the floor operated by a treadle; cleaning implements and the maid's clothing are stored in entry closets; a package receiver can be built into the wall, and the exterior door of the refrigerator opens to receive ice deliveries.26

30 In low-budget houses the same attention to the service system can be seen. A 1920 prefabricated-house catalogue from the Ray Bennett Lumber Company of Tonawanda, N.Y., shows two- and three-bedroom bungalows. The single-floor "Delaware" model has a kitchen just 2.4 m by 2.7 m, which is buffered from its dining room by a small pantry. The kitchen came equipped with a multifunction storage cabinet of the "hoosier" type with a countertop, bins and shelves; an ice-box was built into the enclosed back entry.

31 While newly efficient, the kitchen still had its aesthetic side. Put a plant in the kitchen, advised Frank de Puy in 1900. If a servant does the kitchen work, a plant will make her workplace more artistic, and "if you do your own cooking, you can do it better with cheerful surroundings."27 "Modern housekeeping...recognizes that work cannot be well done unless the mind of the worker is reasonably contented," asserted a House and Garden writer in 1922, hinting that die kitchen worker was probably the housewife and no longer the maid. Since most women now personally directed the menus and selected the foods that their families ate, even if they didn't do the actual food preparation and serving, "inconvenient equipment and dismal surroundings must go...a bright and convenient kitchen is necessary."28

32 One new invention of the turn of the century was the gas stove, which brought the possibility of low-maintenance cooking; the older wood and coal ranges had always needed a fuel supply, and a day's worth of coal or wood had to be hauled from the back porch or basement into the kitchen and stored near the range. Electric stoves also appeared on the market for household use. A major innovation between 1910 and 1930 was the electric refrigerator, replacing the ice-box.30 The ice-box had always been seen as a site for germs and the uncontrollable decay of food.30 In 1920, Clara H. Zillessen, wrote in House Beautiful, "It looks as if the iceless refrigerator — along with the horseless carriage, wireless telephone and tireless cooker — has come to stay."31 Her illustrations show old ice-boxes retro-fitted with mechanical cooling machinery installed either on top of the box or in the basement.32 The separation of the refrigerator into the container on the main floor and the motor in the cellar continued a long history of using the cellar as part of the food axis.33Basements continued to serve as part of the spatially dispersed food-preparation axis into the twentieth century, and outdoor or underground storage structures were still used in rural areas. A Chicago house by Pond and Pond published in a 1915 Country Life in America had "several store-rooms for vegetables, fruits, preserves," as well as the vacuum cleaner and the ice machine in the basement. Noting the relation of food preparation space to the modernized utilities in the basement, home advice-book author Frank De Puy in 1900 cautioned that the cold room for food storage, so common in basements, now had to be especially insulated to protect it from the furnace's heat.34

33 Newly efficient kitchens did not at first affect the middle-class tradition of a segregated dining room, since food odours were still a worry. Architectural writer Martha van Rensselaer observed in 1903 that the kitchen had to be separated enough from the dining room to prevent odours from disturbing "persons at the table or in the living rooms," and cautioned that the back stair can allow "the odor of the prospective dinner" to escape to the second floor if preventive measures were not taken.35 Considering the relation of the dining room to the kitchen, a 1905 author observed that closed doors are essential to impede the spread of odours of cooked food. He recommended a heated and ventilated passage between the kitchen-service-dining end of the house and the rest of the social spaces to take care of "the very objectionable and important question of odor."36 Cooking smells seemed to provide a strong motive to separate the kitchen from the middle-class dining room through the first two decades of the twentieth century. Since kitchens housed mainly women, one wonders if the smell of women was also being cordoned off from genteel social space.

34 However, as more attention was given to the kitchen's furnishings, its organization, and its tasks in the 1920s, the dining room began to wane. Dinner was more likely to be prepared by the housewife herself as servants declined in numbers, so the careful division of servant from served was no longer pressing. Writing in a 1927 Collier's magazine, Edward Bok, influential editor of The Ladies' Home Journal, saw the beginning of the end for the formal dining room. He thought that a segregated dining room wasted space, and added a layer of stiffness and formality ill suited to the mood of the twenties. To replace a formal dining room, a dining area was proposed at the end of the living room, where a table set for dinner could be concealed behind a screen until needed, and china could be stored in built-in cabinets covered with curtains.37

35 While the highest income families preserved their interest in segregated dining and the servants that supported it, lower middle-class households began to merge eating space with kitchen space, condensing functions into a much smaller floor area. In houses of those with lower-middle-class or working-class incomes, the Pullman dinette (also called a breakfast nook) made an appearance. Advertised in the 1920s, the Pullman was a table and benches or seats built into a nook at the corner of the kitchen where the family could take its meals. And, of course, low-budget houses had often combined the living room and dining room functions if two separate rooms were beyond what the family could afford. Sears-Roebuck exhibited a bungalow at the 1910 Illinois State Fair with a combination living-dining room, and a New York firm, Bennett Homes, sold a prefabricated 26' (8 m) by 22' (7 m) house in 1920 in which the principal room was a 10 by 15' (3 X 4.5 m) room labeled "Living and Dining Room."38

Display large image of Figure 10

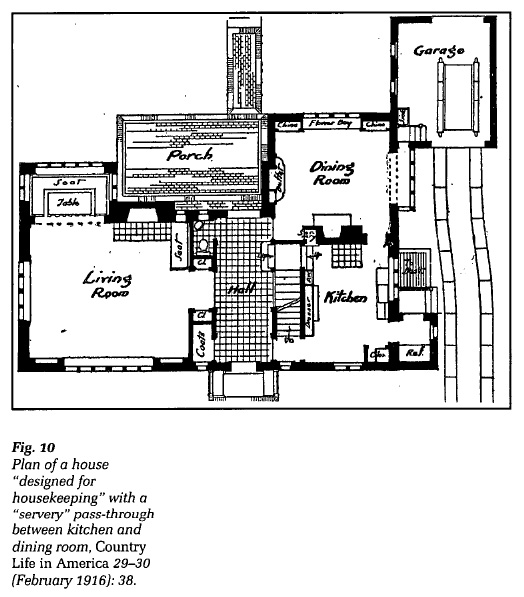

Display large image of Figure 1036 New ways for middle-class home-owners to establish a closer link between the separate dining room and the kitchen, and to do away with the butler's pantry, began to appear in shelter magazines of the 1920s. For the small house or apartment that "employs only one maid," House and Garden advised built-in double-sided cupboards in 1922 (Fig. 10). Such cupboards, with doors facing into both the dining room and the kitchen, "obviate the necessity of a pantry" and also replace the large pieces of dining room storage furniture reminiscent of an earlier generation. In spite of the reference to a maid, the author recommended these cabinets as "a boon to the busy housewife, as they save time, energy and the endless steps spent in going to and fro."39 Thus the change in the housewife's work from managing and assisting in servants' labour to executing the work herself led to simplifying the steps that went into housekeeping; and shrinking the size of the service zone to cut down on steps. Several home economics treatises published 1910 to 1920 mapped ways for the housewife to become more efficient with her movements as she executed the housework tasks. When the labour force in the service zone decreased to one, storage and preparation space needs also decreased.

37 As butler's pantries were eliminated and double-sided cabinets linked the kitchen to the dining area, visual openings from the social zone to the service zone began to appear in house design. The cabinet shelves that open into both kitchen and dining rooms are a feature of Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian houses. But these shelves no longer have doors on them. In Wright's Malcolm Willey House of the 1930s, the kitchen — Wright sometimes renames it "workroom" — is in direct visual communication with the built-in dining area. In the servantless house, the segregation of the housewife's work began to loosen, and the housewife, even while engaged in domestic labour, could enter into the social life of the family and guests, carrying on a conversation across shelves of plates and glasses.40 Electric appliances also fostered the merging of kitchen and dining functions: an "electric luncheon" table illustrated in 1920 presented cooking implements — an electric coffee pot, toaster, omelet pan and "ovenette" — on the white cloth of the dining table.41

38 Barriers between kitchen and dining broke down even further in architecture of the late 1930s and the post World War Ⅱ era. Then an expanded housing market coincided with modernist architectural ideas. Popular middle-class forms such as the ranch house or the Cape Cod bungalow placed all the rooms on a single level with as little buffering as possible between social and service spaces, and without a separate dining room. At the mass-market end of house production, a separate kitchen still prevailed. But at the higher income levels, architect-designed houses brought a new openness to domestic space.

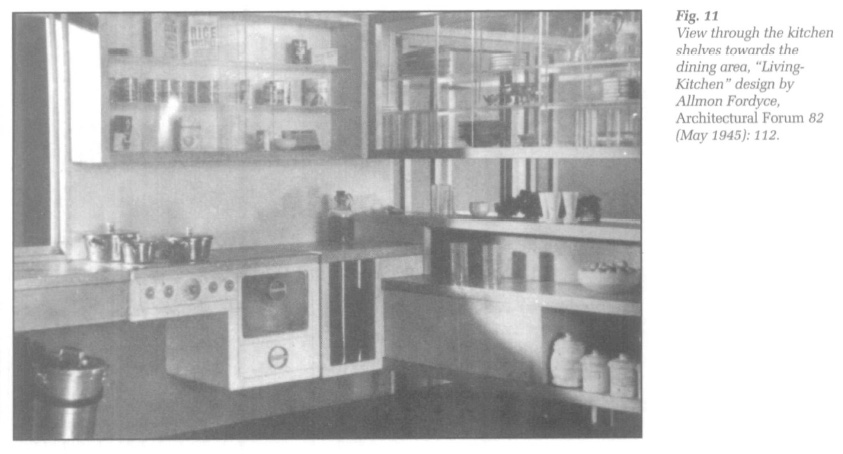

39 This new architectural openness rejected rooms in favour of functional areas. The 1939 World's Fair exhibited the "House of Glass," featuring an open sweep of living-conservatory-dining, with sliding panels that could be used to subdivide the space into rooms should one wish. Even more openness can be seen in the design for a "Living-Kitchen" from 1945 by architect Allmon Fordyce, which was billed as "an answer to the problem of over-specialized space."42 Here the once separate rooms of kitchen, dining room, living room, and utility space are all open to each other (Fig. 11). The dining table and chairs are located at one end of a large living room. Kitchen counter "peninsulas" served to demarcate a permeable boundary between what was once the kitchen and once the dining room, the merged space modulated by counters, fin-walls, and other visually permeable barriers. The once-dispersed food storage places and appliances were now all brought together on a single floor, in a focused portion of the new, merged hvmg-dining-kitchen.

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1140 In Royal Barry Wills' 1954 book, Living on the Level, he equated having a separate dining room with having an old fashioned house. Instead, an open living-dining-kitchen space was recommended.43 Wills too believed that counters, screens and "room-divider" furniture would replace containing walls that segregated earlier spaces (Fig. 2). The merger model was picked up by popular shelter magazines such as Better Homes and Gardens who in 1947 published a "den-dining room." The Mack family of California had taken down the wall that bounded their kitchen nook and joined the space to a too-small den; half-doors opened into the kitchen for "easy service."44The resulting pine-panelled room was furnished with a built-in round table and circular seat, a piano, couch, table and bookshelves. In the 1940s and 1950s, a variety of strategies for merging service and reception activities could be found at all levels of the middle class.

41 The kitchen zone of this new living-dining-kitchen room, where all the house's food-related tools and processes were concentrated, was supported in part by widely-advertised cleaning products. These helped eliminate the kitchen odours from the ice-box and the range that earlier observers had found so offensive. The newly visible kitchen was a beneficiary of several technological improvements. Better-working electric refrigerators, streamlined, continuous-countertop kitchen furniture, washable linoleum flooring, and reliable plumbing all contributed to a kitchen that was cleaner and did smell better than its nineteenth-century counterpart. This kitchen's success as a social space was also due to the efforts of the post World War II era housewife. She was continually reminded by advertisements and magazine articles to have high standards of cleanliness and to devote her days to home maintenance.

42 In cities and suburbs, the new open kitchen's success was also made possible by the proliferation of prepared foods available from grocery stores and restaurants. The three-dimensional site sections of the nineteenth century that revealed a dispersed field of food-storage and preparation spaces can now be replaced by a neighborhood map locating sources for foods and eating sites at greater distances from the house, paired with the concentration of all appliances and food preparation spaces in a single area of the house's interior.

43 These merged kitchen-dining-living areas represented a spatial change that sustained the social change towards a servantless household evident since 1910. Live-in servants were a thing of the past for all but the wealthiest households; instead, Mother took care of the housework and cooking. When the kitchen opened onto the dining area and the living area, housewives at their sinks and stoves could become part of the social activity of the house, not be segregated like a maid in a closed-off kitchen.45 Whatever activities were once understood as service, done by servants, and therefore rightly invisible, were brought into full view now that the housewife herself did the labour. Kitchen labour, reframed as a social activity, might then be seen as "fun," rather than the professionalized skill of the home economists. Conversely, the once autonomous housewife revolving in her efficiently tiny kitchen, is replaced by a housewife in full view of husband, children and guests, available to do their bidding.

44 The culture of the postwar era re-read the old distinctions between work and leisure, clean and dirty, concretized in the service end of the house. Kitchen work, once dirty and smelly, was reinterpreted as a pleasurable and public activity, linked to the pleasures of dining and sociability. Women's housekeeping labour was brought out into the open as part of the general activity of the social zone in a house. The housewife now embodied both servant and mistress; the formerly separated poles of dirt and not-dirt embodied in the kitchen and the dining room were now merged into one. The sign of this divided position could be the hostess apron: made of delicate or fancy materials to adorn the hostess dressed for entertaining, it nonetheless was still an apron, the sign of the kitchen worker.

45 Commercial developers have appropriated the architects' open plans to make an open kitchen-living space standard in 1960s and later single-family houses. The designation "family room" or "great room" is common to name the space that is open to the kitchen and which is used for family sociability and dining. Men too use this kitchen-linked space, and as expert cooking has come to be an admired skill, more men engage in family food production. Some houses with this arrangement still retain a separate living room as a representation of more formal social life, but many builders please their clients by leaving the separate living room out entirely.

46 Recent kitchens in this expanded mode even have couches and easy chairs as part of the furnishings, along with stoves and sinks. Designer Amy Lowell furnished her 1990s kitchen wit a sofa because she had loved that arrangement in a friend's farmhouse, "and she wanted a kitchen that no one could bear to leave after dinner." This sentiment would have been incomprehensible both to genteel Victorians in 1870 and to home economists forty years later.46

47 Since the 1960s more and more middle-class women have taken paid jobs, leaving their living-kitchens for urban and suburban work-places. Neither servants nor modiers could reliably be found in the kitchens of recent times. But the association of food, sociability and emotional warmth with the kitchen continues to affect how modern domestic space is represented. "As life styles have changed, so have kitchens," said a New York Times writer in 1992. "While debates continue about their placement — whether they should be tucked away or integrated into the living quarters — most are designed to be the social core of the home."47

48 What are the gains and losses embodied in this post-war, sociable-kitchen architecture? The merging of reception rooms and kitchens is based on the assumption that the drudgery of kitchen work is a thing of the past and that more of the housewife's day is given over to socializing. If the housewife really had had her work lightened by the new design concepts and appliances, instead of those same appliances raising the standards for and the time spent in successful housekeeping, she might have relished die newly social tenor of her workspace. But since her workload, according to some, actually increased, the new architecture represented only a fantasy of relaxed socializing.48 In practice, an architecture that exposed kitchen mess, smells and work to the view of guests was not easy to accommodate.

Conclusion

49 In this history I have relocated the method of answering an architectural-history question from examining the architect's intentions to observing the users' needs and practices. The open plan, normally explained as a series of evolving aesthetic decisions made by architects, is here explained as a response to a changing set of needs along the food axis motivated by the changing roles of women as household workers and the changing conditions of that work. To better observe the purposes that household space supports, I have proposed another mediodological shift: away from named rooms as containers of activity to the idea of an "activity arena," which may span very extensive space, both within and outside the house proper. This method of accounting for architectural change is an alternative to the usual histories constructed around architects, and offers a way to reveal and explain certain architectural changes that would otherwise remain invisible.