Film and Video Reviews / Comptes rendus de films et vidéos

David Adkin and Arlene Moscovitch, Constructing Reality: Exploring Media Issues in Documentary

1 It seems appropriate in reviewing Constructing Reality: Exploring Media Issues in Documentary to declare my own biases right up front. I am not an expert in film, nor even in media issues generally. As a biographer, though, I am a practitioner of the construction of reality. And as a professor of Canadian Studies, I have ranged through many fields other than my own (English) plucking flowers and thorns identifiably Canadian. Some of these flowers and thorns have been National Film Board of Canada (NFB) films — quite a few, actually — which I have mixed in to the oddly heterogeneous bouquets I offer students. No doubt my ethnicity (second generation Scottish), gender (female), age (early fifties) and class (professional) — to name only the more salient characteristics I bring to this exercise — affect the way I receive what I have seen, heard and read in Constructing Reality. This I will return to later.

2 Constructing Reality is a formidable package of six videos totalling nine hours' viewing time, and a hefty illustrated resource book directed specifically at teachers (who are expected to be "co-learners" with their students). The videos and resource book follow a linear sequence under these headings: What Is a Documentary?; Ways of Storytelling; Shaping Reality; The Politics of Truth; The Candid Eye?; Voices of Experience, Voices for Change — Parts 1 and 2; and, The Poetry of Motion. Clear graphics and a through index by title and subject areas make the resource book simple to use. The package targets "senior secondary and post-secondary" students and aspires to "stimulate critical thinking about key social issues." For this reason, the materials were developed with "media consultants and educators" and "extensively tested in the classroom." All this we are told in a snappy illustrated tricolour flyer filled with glowing quotes from English Canadian (and one American) education and/or media specialists marketing the package. We are also told that this "versatile" package constitutes a "ready-made library of exceptional documentaries for use across the curriculum" and lists nine areas of study for which it can be used: Media Literacy, English, Social Studies, History, Political Science, Journalism, Women's Studies, Native Studies and Art. I emphasize this flyer because it too constructs a reality.

3 There can be no doubt that the NFB has excelled in documentary. Numerous awards and the direct experience of millions of viewers testify to this. One of the films in this package — an edited version of Has Anybody Here Seen Canada? A History of Canadian Movies 1939-1953 — offers historical reasons for the NFB's predilection for documentary. Begun the year World War II broke out, it functioned as a purveyor of anti-Nazi, pro-Allied forces propaganda. Like propaganda machines elsewhere, it pirated materials (confidential and otherwise) and shaped them — sometimes in ways utterly contrary to their original contexts — to inspire and maintain patriotic fervour. To use the trendy contemporary term, the NFB "re-purposed" media material. For example, they overlaid new narration onto recut scenes from the Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will to vilify the Germans. Triumph of the will indeed!

4 History in the form of the NFB's first film commissioner, John Grierson, is also used in Has Anybody Here Seen Canada? to explain the Board's focus on documentary. More than that, the imprint made by Grierson's left-wing politics is made clear. This documentary constructs Grierson as a martyr whose "career was destroyed by allegations of Communist affiliation made in the wake of the Igor Gouzenko affair during the mid-1940s." My own research subverts such a construction. Letters between Grierson and one of my biographical subjects — poet Earle Birney, who was a Trotskyist from 1932 until 1941 — concerned a possible job at the NFB for Birney. Birney submitted left-wing program ideas and scripts to the NFB and later actually did political broadcasts for the CBC in 1946. These letters make it absolutely clear that there were Communists in the NFB and that there was — for a time — considerable panic about various "allegations" which involved behind-the-scenes legal advice of outspoken civil rights lawyer Frank Scott, co-founder of the CCF (Co-operative Commonwealth Federation) in 1936. My point is merely that the use of the word "allegations" (and other strategies used in the presentation of Grierson as a victim) is a fine example of the construction of one questionable reality among many possible versions.

5 What history does not explain is the NFB's continued fixation on documentary after the need for propaganda ended in 1946. Was it simply Grierson's taste? His interests? Or the people he hired over his thirteen-year term as commissioner in an era of undemocratic hiring procedures? This package does not provide the answer.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 My own view is that there is something in the Canadian sensibility that has an affinity for documentary. Or, to turn it around, the strength of the Canadian documentary tradition as proven by the success of the NFB springs from a particular culture. That culture was described by literary critic E. K. Brown in 1943 (at the same time as the propagandistic early efforts of the NFB) as puritanical. Brown observed — rightly I think — that there was an attitude in Canada which was antithetical to the creative arts. He argued that widespread puritanism, which was cultural as much as religious, rendered Canadians suspicious of works of the imagination that were not somehow grounded in fact. Though I think our culture broke free of that puritanism around the time of the so-called sixties revolution — a liberation from earnestness evident in the "sheer aesthetic pleasure" of the last two films on the last video (Flamenco at 5:15 and Sandspit to Dildo) — there is still a lingering tendency (reflected in my own work, I am aware) to verify and document a reality that is clearly shaped and relative, never fixed and absolute. Perhaps our much-pondered identity is reflected in our craving to be educated while we are entertained, our fears demonstrated in the contrast between decadent, money-grubbing Hollywood and a serious, idealistic NFB. Or, perhaps this preoccupation with facts is a legacy from a not-so-distant colonial past. Maybe we're still plagued with insecurities about whose reality (British? American? And now, central Canadian? Bicultural? Multi-cultural? Regional?) is really real. We want documentary proof.

7 Whatever the validity of these speculations, there seems to me something very Canadian about this whole package — "Canadian" of course being defined by me as result of teaching over a decade of classes on the subject, defined now, not as I once saw it or may see it later. I recognize the generally earnest tone, the focus on the use of historical materials to educate, the anti-Americanism, the uncomfortable inclusion of French Canada (for this is really an English Canadian production), the self-deprecation involved in revealing mistakes and behind-the-scenes difficulties, the Leacockian humour of the small guy at the big bank, the moral agonizing, the idealistic commitment. For this reason alone — quite apart from the explicit teaching strategies so carefully "tested" and glowingly praised — Constructing Reality is valuable as an expression of what this culture is like. To watch these videos and read the resource book is total immersion in our (English-) Canadian sensibilities(s).

8 I say this because, given my background, I saw what I expected to see. My views of Canada are largely confirmed here. Take the early NFB production on the Klondike by Pierre Berton, City of Gold. Apart from my predictably emotional response to the pervasive and crucial mythology of The North in this country, I grew up with Berton, the Maclean's journalist (who was featured as having been prophetic in his youth in my newspaper yesterday) and Berton, the 1950s Front Page Challenge panelist (another "educational" Canadian entertainment and forerunner of the Canadian game Trivial Pursuit), and I myself wrote a long profile of Berton for Saturday Night in 1987. Or take Our Marilyn, which juxtaposes film footage of Marilyn Monroe and Canadian swim champion, Marilyn Bell. I was in grade school when "our Marilyn" swam Lake Ontario in 1954, and one of the generation of teenage girls for whom "our Marilyn" was the epitome of female desirability. Or take Lonely Roy, about Paul Anka, whose LP records I owned in the 1950s. Or Ladies and Gentlemen: Mr. Leonard Cohen, a film I first saw in 1966 at the launch of Cohen's novel Beautiful Losers in Toronto (oddly, since the novel was set in Montreal where Cohen dien lived) where I saw the enigmatic Mr. Cohen himself gaze at the film in which he watches an excerpt of the same film in which he scrawls caveat emptor (let the buyer beware) on the wall as he takes a bath — a post-modern experience long before the term post-modernism existed. Later, I discovered through research, NFB director Donald Brittain had re-purposed footage intended to cover a tour of four poets — Leonard Cohen, Irving Layton, Earle Birney and Phyllis Gotdieb — because he was beguiled by Cohen, who was then just emerging as a singer and cult figure.

9 Nor am I any stranger to the issues of aboriginal land rights and cultural disintegration, the violence men visit upon women, the obstacles black women face in Canada, the brutality of war — especially as it affects hapless children — and the concomitant peace movement. I could go on.

10 But what about the reality inhabited by the "senior secondary and post-secondary" students for whom this package has been prepared? I do not presume to guess what their reality or realities might be. Nor can I know the reality of their "co-learner" teachers — most of whom are much younger than I am. All I know (as the parent of three children between the ages of 17 and 25) is that their reality not only is different from mine, it is constructed differently. "Who is Paul Anka anyhow?" asked a number of the students on whom the videos were tested. Good question. Even his later hit "Having My Baby" is a retro glimpse of post-war breeders in domestic bliss, not a hook on which to hang current sensibilities. How does Leonard Cohen seem to a generation for whom the very name "Leonard" — for some reason I could never grasp — always provoked gales of laughter? Essence of nerd, I suppose.

11 It is possible that Constructing Reality can be used successfully in teaching media issues in the classroom, but surely it will be received by the Nintendo generation — or, if you like, Generation X — in ways the producers of the package can't even imagine. If McLuhan is right — and I believe in tins he was right — changes in technology affect everything in human beings from body language to perceptual patterns. As we wait poised at the edge of Virtual Reality, I fear that an instructional package such as this is antediluvian before it is produced. Despite the hat tipped to education as "interactive" (a metaphor constructed from a reality that even predates mine), the historical linear approach that largely informs this series is probably alien to kids who surf channels, cruise the Internet and socialize in "Wayne's World." Making allusions to the Gulf War, Oliver Stone's JFK, the Rodney King beatings, Madonna or Full Metal Jacket (all, I note, linked in some way to 1960s preoccupations) will not just date the resource book immediately, but are examples of an educational strategy (allusion) that has little, if any, meaning to what I think is an ahistorical, culturally chaotic generation.

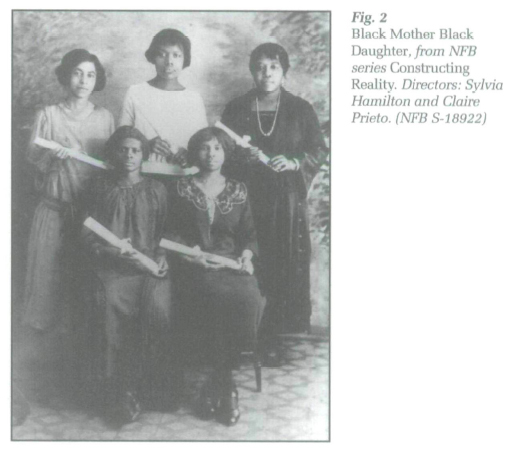

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 Despite this criticism, I think there is much in Constructing Reality that is superb. And timely. The process of shaping images for media purposes has become a popular and important subject. Stars such as Michael Jackson — even feminists like Gloria Steinhem — shamelessly reveal their cosmetic "improvements." Politicians consult media image experts, and change their styles accordingly. Television goes behind the scenes in "the making of such-and-such a film" programs. We see athletes in locker rooms and in replays on the field. Even the strict conventions governing news broadcasts have loosened to show camera, lighting and sound crews at work on artificial studio sets as they draw back from the illusion of official news offices at the end of such programs. How media spells are cast has replaced the spell itself.

13 Constructing Reality is an incisive examination of this same process. A number of video segments unmask and demystify the naive illusion that documentary equals truth. The most humourous of these are The Spaghetti Story, a short, excruciatingly witty parody of the "educational" documentary and Track Stars, which uses the split screen to show both an action film and the truly slapstick antics of the two "foley artists" in the sound studio energetically producing the sounds that match the film's action (the sound of body punches, for instance, are made by slugging a huge side of beef hung mid-studio). The Edit addresses a subject poorly understood in publishing as well as in media in a mini-drama that demonstrates that whoever controls the scissors controls the message an unwitting public believes. Interviews with film directors and subjects indicates the degree to which the end result can diverge from the original inspiration. The use of fantasy and black humour in New Shoes, one woman's account of an attack by her armed ex-boyfriend, an interview with executive director Ann Marie Fleming, and the explanation of the animation techniques in the resource book, show the different ways in which a personal story can be constructed into more than one reality.

14 Constructing Reality is also useful as a handbook on media techniques. A two-page spread cartoons the people and start-to-finish process of documentary making. But though the explanation of "gaffer" and "best boy" and "grip" enlighten people like me, I think the technique of film-making must necessitate hands-on experience of a type this package cannot offer. Despite lengthy explanations and numerous video examples of such techniques as the use of stills, voice-over, music, scripted narration, archival footage, silence, cartoons, superimposition and so forth, any course on media literacy using these materials would surely be an introductory one. And even then, students accustomed to a diet of multi-level, experimental music videos and stunning special effects in popular movies like Steven Spielberg's or the Terminator series are likely to echo the sentiments of one of the students interviewed in 1993 for "What Is a Documentary" — "It's boring."

15 What will probably not be boring for Generation X students is the many-layered theme of social issues. Ironically — given that their orientation to these issues is so different from the NFB's 1960s consciousness — students rendered introspective, cynical and playful by unemployment and the intractability of such aspects of life as the environment and global homogenization, connect with the marginalized groups (women, Jews, Métis, blacks, refugee children, aboriginal peoples) so often vindicated in the leftish social crusades of these documentaries. In this way, the propagandistic and left-wing social purposes established and maintained by Grierson has mutated over time and seems likely to endure. I found the most poignant videos were Richard Cardinal: Cry from the Diary of a Métis Child, a horrific tale of an unwanted displaced child who hanged himself at age 17 after living in 28 foster homes, and Of Lives Uprooted, a sequence of drawings by children who had escaped political violence and persecution depicting their experiences. Both films use original documents (Richard Cardinal's diary and the children's drawings) for maximum effect. And both are aimed at improving society. Director Alanis Obomsawin's indignant and impassioned commitment in producing Richard Cardinal resulted in fundamental changes to Alberta's Child Welfare Act (including the right of aboriginals to run their own social service agencies) after the documentary became compulsory viewing for social work students.

16 The two videos which impressed me most were Docudrama: Fact and Fiction and Our Marilyn. This, of course, reflects my current interests and cannot be construed as being of much use to others. To describe why I liked these two sections of the package, however, will give an idea of how the package as a whole works. The same principles and methods are used throughout Constructing Reality.

17 Docudrama: Fact and Fiction draws attention in its title to the vexed question at the heart of all communications purporting to be true. How much is fact, and how much is fiction? Truth, of course, is not mere fact. Even that most rulebound theatre of all — the courtroom — acknowledges the importance of tone of voice, the presence or absence of such emotions as remorse, the demeanour of witnesses. The significance of an event can be changed radically depending on where the account of it begins and ends. Reality is constructed, even in presentations that seem to stick literally to a sequence of events. In fact, cinéma vérité may be the most manipulative of media. All documentary, this package of materials teaches us, is to some extent "docudrama," though the term applies specifically to the melding of actual footage with scripted scenes played by actors in such a way that the boundaries blur.

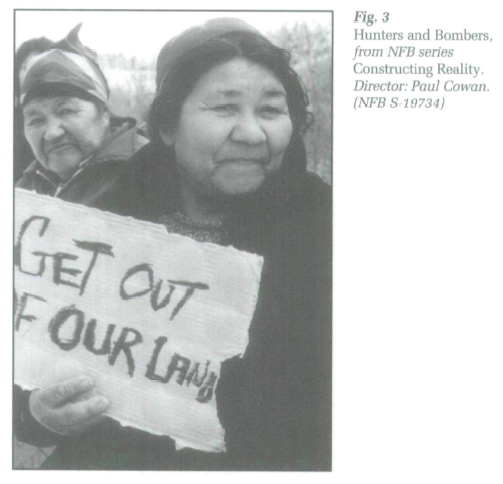

18 The case in point is a public forum held at McGill University by ten NFB filmmakers in 1986 to explore the complex issues raised by the emergence of the hybrid form of docudrama. Screenings of films alternated with question and answer sessions involving panelists and audience. Docudrama is a segment of this forum: one in which filmmaker Paul Cowan defends his docudrama on World War I pilot Billy Bishop, The Kid Who Couldn't Miss, against attacks from members of the Canadian Air Force Association, who disputed the accuracy of several aspects of the film. Both sides in this dispute are convincing, a balancing technique that is useful for classroom debate.

19 Memorable to me — for I have faced such decisions in writing biography — was the discussion around Cowan's deliberate falsification of an aspect of Bishop's childhood. Bishop's father paid fifty cents per squirrel for each one he shot, an obvious opportunity for a filmmaker or (biographer) to employ the creative literary technique of foreshadowing: first squirrels, then Germans. But Cowan — wishing also to anticipate Bishop's efficiency in downing enemy aircraft — changed the squirrels to ducks. Further, by using jerky hand-held cameras and scratched black-and-white film to record a boy actor playing young Billy shooting ducks and holding them up in triumph, he constructed an illusion of real amateur movies somehow saved by the Bishop family. The resource book suggests that teachers ought to ask students whether or not Cowan ought to have alerted viewers somehow that this "old footage" was faked. Answers to this question lead naturally into discussions of the different kinds of truth available to makers of documentaries, and the significance of such choices.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 320 Our Marilyn makes no such pretense of "objectivity." It is an intensely personal presentation by independent filmmaker Brenda Longfellow through "Studio D," the NFB's Women's Studio, founded (we are informed in the historical introduction to the resource book) in the 1970s. Longfellow uses a fictionalized narrator based on herself as a young woman whose name — Marilyn — causes her to muse on the two sets of female possibilities posed by her namesakes Marilyn Bell and Marilyn Monroe. The video is decidedly feminist and nationalistic. The set of possibilities represented by the American Hollywood star (who, at the time Bell swam the lake, was entertaining troops in Korea) emphasizes the decorative aspects of the sex goddess who is "blonde, vulnerable, weak, exploitable." In contrast, the set of possibilities represented by the Canadian swim champion (who not incidentally defeats her American rival Florence Chadwick) emphasizes the swimmer's usefulness as "the little virginal person of stamina and endurance." The symbolic significance of this contrast — in which feminist values are linked to Canadian characteristics — was deliberate for Longfellow who says in a fascinating interview about her aims and methods in the resource book, "For us, these are great Canadian qualities — not as snazzy as Monroe, but nevertheless they seem to be part of the way we collectively think about our heroes." This observation tallies with much I have learned in my lengthy consideration of things Canadian. Longfellow's complicated methods, through which she creates a dreamy atmosphere that re-creates the rhythmic breathing of the swimmer and merges it with the breathy voice of Monroe, are described in full and demonstrate the extent to which creative filmmakers can go in experimenting with the construction of reality.

21 In showing what goes on behind its own scenes in Constructing Reality, the NFB offers a number of valuable lessons. These may or may not be what those who put together the package intended. How these materials are received will have as much to do with those receiving them as with those generating them. Classroom tests of the material provoked students to conclude that behind the media lies conspiracy of one sort or another. This is the great risk in showing how the magician does his tricks. I fear that Constructing Reality may result not in healthy scepticism, but in bitter cynicism. I think much depends on the way these materials are handled by teachers; and that, in turn, depends on who those teachers are.

22 I hope that those teachers see that Constructing Reality is itself "constructed." I hope they point out to their students that the NFB is also constructed. The view we have of ourselves as a result of watching NFB productions depends precisely on who made any given film. Who chose the subject? Who decided how it was to be treated? What were the purposes of those who re-purposed archival footage? Who did the edit, the interviews, the narrative script? And behind that, why were these people hired? What criteria were used to select them at the NFB rather than other applicants? If Canadian documentaries are instruments of social change, who is defining the issues and directing that change? Whose Canada are we seeing when we see Constructing Reality?

23 Will Constructing Reality excite young filmmakers to experiment with the possibilities of documentary? Yes, I think so. Will it enlighten people of all ages about the nature of audio-visual media? Depending on differing degrees of awareness, yes. Has anybody here seen Canada? Yes, but let the buyer beware.