Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, Remembering Our Warriors: A Tribute to Manitoba's First Nations Veterans

Manitoba Indian Education Association

1 May 1995 marks the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II and the beginning of an era that sees First Nations communities coming forward to recognize members of their communities who have made contributions to Canada's war efforts. Approximately 3 500 individuals out of 106 500 First Nations members served in WWI alone.1 The public is constantly being reminded that First Nations veterans are "forgotten soldiers," but why are they referred to as "forgotten." First Nations soldiers will tell you, "we came to the call of duty when our country needed us, and were proud to do so, only to return to a country that forgets our contributions." Other veterans have said, "while we were in the service we thought of ourselves as Canadians first, before we were Indians, and if your life depended on saving yourself and your comrade's life, whatever his ethnic background, you did just that." Thoughts like these of patriotism, heroism and courage will always remain in the minds of First Nations veterans who themselves made near ultimate sacrifices in the name of freedom. For the remaining days of their lives they, along with their families, will continue to suffer psychological effects due to the horrors of war.

2 In November 1993 (75 years after the end of WWI), the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature hosted the exhibition Remembering Our Warriors: A Tribute to Manitoba's First Nations Veterans (Fig. 1). The exhibit included wartime memorabilia, photographs and historical information detailing the involvement of Manitoba's First Nations communities in Canada's war efforts. The focus was to provide both the aboriginal and non-aboriginal public with an awareness and appreciation of the contribution First Nations communities made to both world wars and Korea. The exhibition was about First Nations veterans. It brought to the forefront examples of the sacrifices these veterans made for their country. It was the perfect opportunity for First Nations veterans to come forward with their stories and experiences and it provided a forum for the public to respond.

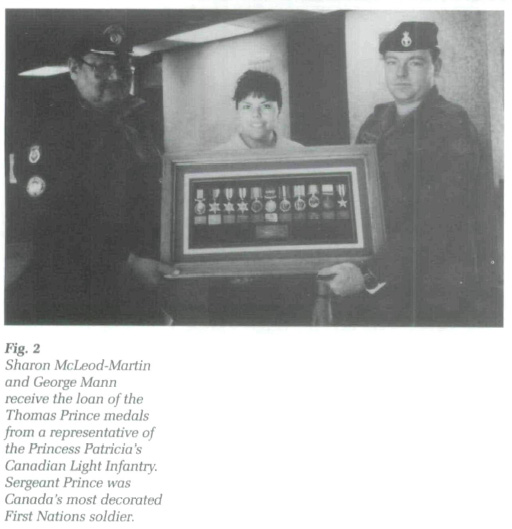

3 The exhibit was a collaborative effort between the curator and the Manitoba Aboriginal Veterans Association of Manitoba Inc. under its president, George Mann. Originally from Fort Alexander First Nation in Manitoba, George Mann is a veteran of 25 years of service, and served overseas in both Korea and Vietnam. He possesses a wealth of knowledge and military experience gained through his years as a paratrooper. He also served with Sergeant Thomas Prince, Canada's most decorated First Nations soldier (Fig. 2). Mr. Mann served as a liaison between the museum community, military personnel and veterans within his association. He volunteered many hours to proofread written material, explain military jargon and coordinate community consultations between the veterans and military personnel. His genuine interest in and excitement about participating in the project, and his enjoyment watching the whole project come together and observing others who were involved in producing the exhibit will always be remembered. It was a dream come true for him.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 24 The project was completed with a very minimal budget. The main source of funding was the training budget allotment for exhibit development. Extra hours, travel time and expense money came out of the pockets of both the curator and Mr. Mann. There was also extensive voluntary community involvement. One cannot express enough gratitude to all individuals who gave their time and effort to this project. This is a good example of what can be accomplished with limited financial resources but plenty of community support.

5 The project initially took the traditional academic approach that was necessary to develop objectives. As time elapsed, the project diverted its attention from the academic realm to accommodate sensitivity. It became more and more obvious that a very personal approach was needed to meet the objectives of the exhibit. These objectives were: 1) to provide information on the number of First Nations veterans in Manitoba who served in the world wars and Korea and on the communities they represent; 2) to explain the reasons members of the aboriginal population enlisted even though they were exempt from military service through the Military Services Act; 3) to summarize an individual's experience in a case study to show the affects of the realities of the war; 4) to provide a summary of the veterans' integration back into society after the war years; 5) to present evidence of the veterans' efforts to maintain their aboriginal identity; and 6) to present some of the outstanding contemporary issues that First Nations veterans face.

6 These objectives were the showcase of the exhibit and presented some of the issues First Nations veterans face when taking up an active role in the military to the public at a glance. Further attention should be given to these areas so that serious research by First Nations governments and by academics in various disciplines (such as historians and sociologists) can begin. It was hoped that by presenting these issues a sense of understanding would be generated and a new appreciation of the contribution these veterans made would be gained by the viewers. The exhibit by no means provided answers or solutions to political and social issues which still exist. Veterans continue to wrestle with these issues. However, time is running out, as the government continues to delay resolving these veterans' outstanding grievances.

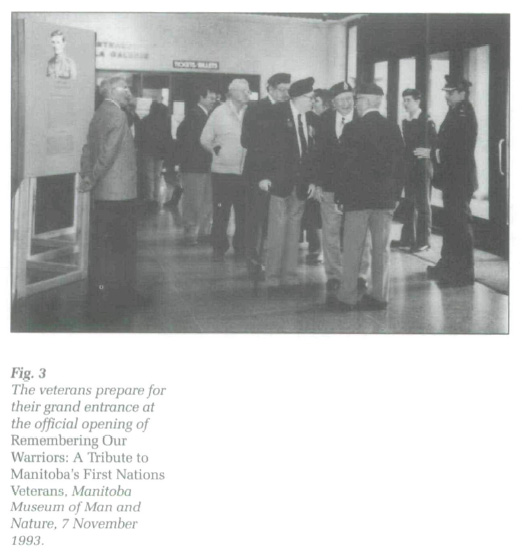

Military Objects Tell Their Own Stories

7 As with any informative exhibition, it was necessary to secure exhibit artifacts and other materials that would tell their own stories and bring the exhibit picture into focus. The first source of such objects that came to mind was the museum storage area. It should have been a simple matter of pulling out a few items for display. This was not the case in this particular exhibition. The only items that were available were some uniforms and pictures. Although they had some intrinsic value, the objects did not adequately tell the story of a First Nations veteran at war. This pointed out the lack of items in existing museum collections that could have been used for the exhibit, and the search for appropriate personal military memorabilia began.

8 There were visits upon visits to local military museums, and many phone calls to the curators. After a few of these visits it became obvious that the search for objects would lead us elsewhere. What was in the museum collections that could be used in the exhibit was of limited value. Upon further evaluation, it was agreed that Mr. Mann would have to draw upon his own personal memorabilia and his contacts to borrow personal items for display. The call to arms was answered, and a wealth of artifacts was gathered. Needless to say, this is the reason the artifacts displayed in the exhibit, apart from the eaglefeather headdress, bear claw necklace and the Hong Kong Veterans jacket, belonged to veterans and their families.

9 The Hong Kong Veterans jacket was choosen for display because of its significance to First Nation veterans who became prisoners of war in 1941 in Japan. This particular artifact was one of Mr. Mann's favourite pieces in the display. James A. Moar, originally from Crane River, is one such surviving veteran who was held prisoner from 25 December 1941 until the end of the war in 1945. When Mr. Moar was contacted about the exhibit, he graciously accepted Mr. Mann's invitation to attend the opening reception that was schelduled for Sunday, November 7th.

10 Coming down to the final days before the exhibition's opening, there was still the need to obtain additional artifacts for display. At this point Mr. Mann announced the loan of a private collection that was due to arrive within a day or so from the widow of Pte Maurice Bone from the Keeseekoowenin Band. The collection contained some photographs, a biography in a Plexiglas stand, personal medals, discharge papers, a letter written by the veteran to a family member back home, a soldier's pay book and a "record of equipment" book. These were the type of items that we were originally searching for. The collection was displayed in its own exhibit case. After the display period, appropriate conservation measures were undertaken and the Maurice Bone collection was returned to the family with an acknowledgement of thanks. Given more time, additional items being held in the safe keeping of family members could probably have been located and secured for the exhibit. Items such as these will always have sentimental value to family members as part of their personal history. This points out the need for museums to accommodate the development of various themes in the interpretation of local military history.

Day of Honour and Recognition

11 In conjunction with the exhibition, the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature hosted an opening reception on Sunday, November 7th. "Meet the First Nations Veterans Day" received a remarkable response from both the viewing public and the media. Over 100 people were in attendance, including First Nations veterans, families, friends, local dignitaries and media personnel. The opening ceremony was intended to give the veterans an opportunity to view the exhibit first hand, to provide feedback on what they saw, and to share their responses with their comrades, family and other people in attendance (Fig. 3). The event had its own special meaning for each veteran and brought about a sense that it was something that was long overdue. The opening ceremony was also to inform the viewing public that the special exhibition was on display. Through the use of the media, more people were made aware of the exhibit. There were television news reports on local channels and newspapers carried articles about the exhibit. This all helped spread the exhibit's message.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 312 Young First Nations military personnel who may become the future generation of First Nations veterans with their own stories to tell (depending on where their military careers take them) attended the opening event. Three young First Nations members of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles cadets presented a foot drill demonstration near the end of the program (Fig. 4). Also in attendance were Metis soldiers, Master Cpl Darcy Neepin, with the Queen's Own Highlanders, and Cpl Nathan Guiboche, a reservist with the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, who had a family member serve in WWII and not return home.

13 The "day of recognition" also had political connotations for First Nations veterans. The mayor of Winnipeg, Susan Thompson, signed a Proclamation establishing 8 November 1993 as Winnipeg's Day of Recognition for First Nations Veterans. It is ironic that, one year later, the province of Manitoba declared November 8th "Aboriginal Veterans Day." The exhibit may or may not have played a role in this decision. What the exhibit did accomplish was to demonstrate strong community support in both the aboriginal and non-aboriginal communities for the First Nations veterans. This is clearly a step toward building the bridge toward social justice and harmony.

After the War Years

14 Time is an enemy that First Nations war veterans cannot fight against and hope to win. As each year passes, so do the lives of our veterans, and with them, their stories of the roles they played in Canadian history. There are few veterans left from World War I, if any, and 50 years after World War II, surviving veterans of this war are now entering their most senior years. Similarly, the retirement years for the Korean and Vietnam veterans are fast approaching. Time is slowly taking away valuable memories and experiences of these veterans of foreign battlefields. One can only hope that their memories can be recorded before it is too late.

15 The exhibit conveyed the message that these First Nations soldiers have managed to maintain both a sense of their cultural identity and loyalty to their country. Military training instilled in these soldiers a sense of duty to the Queen and to Canada. At the same time, they never forgot where they came from: small rural First Nations communities. These individuals became unique soldiers. Some, particularly those who have experienced actual combat, find it hard to share the horrors of war with those who weren't there because of their experience in the service. It has been observed that First Nations veterans take oath to themselves on who they will share their experiences with. The exhibit was fortunate enough to have veterans who took part in the exhibition share their memories and stories.

16 In order to produce this exhibit, it was important to gain trust and understanding of these forgotten soldiers. While compiling the research material, the veteran's feelings were taken into consideration in order to uncover their true stories and experiences. As Mr. Mann mentioned to the curator after the exhibit was over, "After observing you when I first met you, I knew that this was someone that I would want to work with." Being accepted by the veterans becomes more of a moral and ethical issue as well. In future exhibits, aspiring curators would be wise to observe the standards that were used in producing this exhibit. If an exhibit's purpose is tell a small story about a certain time period, then uniforms and pictures from the museum collections will suffice. However, if a true picture of that particular time period is to emerge, then the feelings of the people who have experienced it must be captured. This will give the public a better sense of what the exhibit is all about.

Conclusion

17 Manitoba should be proud of what it has accomplished on behalf of its First Nations veterans during the last few years. The exhibition was just a ripple in the recent wave of activities. It provided a historical perspective of First Nations contributions, and also highlighted some contemporary issues that First Nations veterans face. The items on display had a personal history behind them, which made the exhibit more meaningful to those who contributed. The awareness that has been created will have a positive impact in the future.

18 Several projects have been initiated since this exhibit was completed. A grant was received to conduct oral histories in the communities of Norway House and Cross Lake in northern Manitoba. Efforts are also being made to produce a travelling exhibit based on Remembering Our Warriors. The Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature hopes to incorporate some of this material into their Parkland and Mixed Woodlands Gallery (a permanent museum gallery). If these projects are completed, the experiences of First Nations veterans will be recorded. However, much more work is needed to fully understand the impact of war on its people and their communities. The oral history projects of Manitoba's surviving First Nations veterans need to be coordinated, statistics need to be compiled, organized and stored as an information base, and existing archival and resource centres need to be expanded, or new centres established, to house the memorabilia and material of the veterans.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 419 This is just a brief list of projects that would assist First Nations veterans in securing their identities as First Nations people in the military. The reality is that time is going by too quickly, and there are many more Tommy Princes out there who have yet to be remembered for their war contributions.