Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

National Building Museum, Washington, D.C., World War II and the American Dream: How Wartime Building Changed a Nation

Duration: 11 November 1994 to 31 December 1995

Publication: Catalogue, World War II and the American Dream: How Wartime Building Changed a Nation, Donald Albrecht, ed., National Building Museum and MIT Press (in press).

1 "I just want to say one word to you, just one word," said Mr McGuire to the 20-year-old Benjamin Braddock in the classic 1967 film, The Graduate, "plastics." For director Mike Nichols and indeed, for many of us born in the prosperous post-World War II era, this magical stuff summed up the hopes and aspirations of the newly materialistic middle class.

2 The exhibition World War II and the American Dream: How Wartime Building Changed a Nation, currently at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., showcases plastic, as well as plywood, water-based paint, aluminum siding and a host of other materials that still constitute our everyday domestic landscapes and were originally designed for wartime use.1 Frozen foods, saran wrap, tupperware and melamine dinnerware are displayed amid Quonset huts, the Pentagon, and the ubiquitous post-war suburb, underlining the old aphorism, "necessity is the mother of invention."

3 The overall aim of the exhibition is to illuminate the constructive, rather than destructive, side of the global conflict that took place a half-century ago. It is installed in five or six relatively small galleries located off a corner of the museum's Great Hall. A P-39 Airacobra fighter plane hangs from the ceiling, marking the entrance to the galleries. Loosely organized around the themes of mass production, Washington during the war, wartime research, housing and cities, and household products which emerged from the war, the show comprises about 350 objects and images. In material culture terms, it proceeds from the large-scale artifacts (Quonset huts, highways and blimp hangars) to smaller, domestic objects in a fairly linear fashion.

4 The real power of the exhibition is that it tells the story of World War II through things, rather than events, and focusses on that most materialistic of nations, the United States. In fact, parts of the show suggest that America's unsurpassed capability to produce all sorts of things — not just A-bombs — was at the base of the Allied victory in 1945.

5 One of the most interesting (and telling) aspects of the show is the design of the display structures themselves. Although rather shabbily built — they were self-destructing on opening day — the frameworks for the models, objects and images were directly inspired by the theme of the show and served to underline its major points. For example, the space accommodating the final section on home life during and after the war is defined by a gable-shaped wall veneered in fibreglass insulation and aluminum siding; some walls are slightly canted to suggest the ways prefabricated ones were raised up to construct cheap wartime housing; the tables supporting the models look like the landing gear of airplanes; and everything is grey, evoking the functionalism of bare metal and the composite dullness of khaki uniforms.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

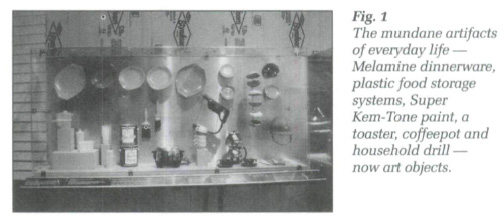

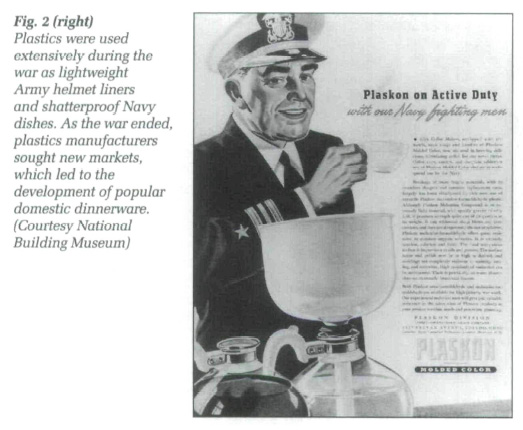

Display large image of Figure 36 Less successful is the suggestion of any kind of social or cultural context for most of the artifacts. The exception to this general criticism is the section on urban issues, which is full of photographs and maps and illuminates the double standards experienced by black workers during the war. The parts of World War II and the American Dream, however, that focus on the smaller stuff of everyday life present rather mundane artifacts like so many art objects, devoid of any social meaning. Melamine dinnerware, plastic food storage systems, Super Kem-Tone paint, a toaster, coffeepot and household drill are all carefully arranged behind glass (or is it Plexiglas?), emphasizing their now precious value (Fig. 1). This display case is situated between an open fridge of frozen food and Buckminster Fuller's model of the aluminum and plastic Dymaxion House. A single helmet included in the all-domestic ensemble reminds viewers of the development of plastic during the war for lightweight Army helmet liners and shatter-proof Navy dishes (Fig. 2). Marketed after the war for their bright colours, durability and high sanitary standards, cups and plates of melamine-formaldehyde were embraced by the typical post-war middle-class family, who placed a premium on both safety and cheeriness in the arrangement of their cozy, post-war nests.

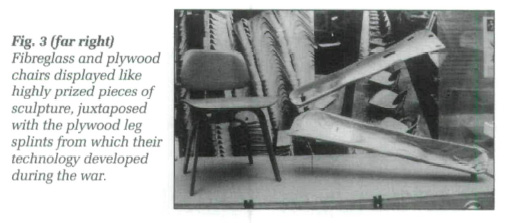

7 Similarly, fibreglass and plywood chairs, like the ones still found scattered around libraries and cafeterias of most Canadian universities, are displayed like highly prized pieces of sculpture, juxtaposed with the plywood leg splints from which their technology developed during the war years (Fig. 3). It is ironic that such functional, well-designed and cheap objects are presented, 50 years later, in poorly built (although very hip) and undoubtedly expensive museum cases.

8 The glaring omission of social issues is truer of the exhibition itself than of the 280-page catalogue of the same name, which unfortunately was not available for the exhibit's opening on Veterans' Day, 1994. Essays by Margaret Crawford and Greg Hise, in particular, provide the much needed historical grounding missing in most parts of the exhibition. There is little suggestion in the museum setting, for example, of how the advent of frozen food affected the lives of countless middle-class women suddenly forced back into the home to reproduce. As many historians of technology have shown, the "perfect results" promised by TV dinners, Spock-style parenting, and the crisp, under-rated walls of Modernist architecture led directly to the "problem that has no name": the Feminine Mystique. What happened when millions of men traded their khakis for grey flannel? According to this exhibition, everybody lived happily ever after.

9 To be fair, World War II and the American Dream does reveal how many of the things usually assumed to be developed in post-war America, especially the middle-class suburb, actually began in the desperate years during World War II. In this sense, the show succeeds in underscoring both the impetus to create new technologies fostered by the war effort and the rapid conversion of wartime production to the needs of post-war consumer society. For those of us who grew up in post-war suburbs playing with perfectly shaped (plastic) Barbie dolls, cooking tiny cakes in Easy-Bake ovens and consuming processed cheese sandwiches lovingly sheathed in Saran Wrap, these points strike a real chord. It is fascinating to learn, for example, that this multi-purpose plastic film still found in most of our refrigerators was first developed to protect machine guns from moisture during shipment to the front lines.

10 Unfortunately, the exhibition's celebration of American technology — sponsored, not incidentally, by the U.S. Department of Defense — provides no hint of the negative impact of mass-produced consumer technologies. Plastics, after all, were never the problem-free miracle product promoted by the Mr McGuires of the world.