Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Carl Poul Petersen:

Master Danish-Canadian Silversmith

1 Carl Poul Petersen (b. Copenhagen, 1895, d. Montreal, 1977) drew his inspiration from Denmark's rich folk tradition, its silver tradition — especially the restrained brand of Danish modernist silver of the Georg Jensen Silversmithy — Danish culinary silver and the Smorgasbord buffet tradition, and Danish silver plate. Art silver of C. P. Petersen & Sons also fits within the sphere of Scandinavian pre- and post-World War II Quebec craft. The master silversmith was among the Danish émigrés to North America before the war who brought with them their rich heritage of craft and craft techniques. Since non-objective fine art has been so well-documented as mainstream Western art during the period that Petersen was active in Quebec, pluralism in the art community should now include and evaluate the role of the European émigrés and their unique contributions to provincial culture.

2 Scandinavian design grew from its strong background of sea and forest. In the interwar and post-World War n periods, Denmark built up an international reputation in varied areas of design. The prestigious Royal Flora Danica eighteenth-century porcelain table service of 1 602 pieces, painted with botanically-accurate renderings of Danish wild plants by Johan Christoph Bayer after J. C. Oeder's book on Danish flora1 offered one important model for Danish naturalistic imagery.

3 Petersen domestic and ecclesiastic silver should also be examined along with other emigre art and art-silver for its singularity during the period in question. His modernist silver should be examined alongside those of his Quebec contemporaries in the precious metals such as the work of Georges Delrue (b. France, 1920), Maurice Brault (b. Montreal, 1930), Arthur Guyot (1895-1957), Bernard Chaudron (b. Lille, France, 1931), Giles Beaugrand (b. Montreal, 1906), Roger Gabriel Lucas (b. Montreal, 1936), Walter Schluep (b. Spain, 1931), Hans Gehrig (b. Switzerland, 1929) and the fine custom jewellery of Thomas Primavesi (b. Austria, 1925).

4 The artist-craftsman emigrated from Denmark with his wife, Inger Jensen (1900-1976) whom he had married in 1922. They arrived in 1929 in Montreal at the start of the Depression, hard-hit by the financial crash, and with the silver market in sharp decline. Petersen was already an established master goldsmith as the trade was then called. According to his sons, their father had studied the fine arts in Copenhagen. It is even possible that he attended the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. He had been a sculptor in his youth, and he had taught drawing in Copenhagen.2 During the 1920s, the young, sociable, personable, tee-totalling Petersen of the jazz age participated in the Arts and Crafts movement occurring in Danish craft circles. Studio crafts people, furniture designers, weavers and architects as well as silversmiths were all turning Denmark into a centre for the crafts industry.

5 Danish twentieth-century silver came into its own in the somewhat isolated handcraft-oriented country fuelled by Arts and Crafts movements, by the fanciful naturalism of Austrians Josef Hoffman's and Dagobert Peche's silver design from 1903 to 1932 at the Wiener Werkstatte (Vienna Workshops) and by simplified Japanese design at the turn of the century via British nineteenth-century aesthetics, as a result of the development of a new national style emphasizing streamlined form, with ornamentation serving to set off that form. (According to British Arts and Crafts, ornament should only enrich the essential construction of an object.)

6 Danish silversmith Georg Jensen (1866-1935) integrated the ideals of William Morris into twentieth-century Scandinavian silver.3 Georg Jensen is considered the seminal figure in twentieth-century Danish silver. Plant forms inspired much of his decorative work. His most notable designs came out of the short-lived art nouveau period from the late-1890s to before 1920. An entrepreneurial genius as well as a master craftsman, Jensen paved the way for the commercialization of silver. His workshop, founded in 1904, still produces new and reissued silver.

7 Carl Poul Petersen was apprenticed to Georg Jensen, probably from the age of thirteen according to family information, for a five-year stint, the necessary duration of a journeyman-apprenticeship, after which time apprenticeship pieces were judged and approved and one became a master.4 The art school and trade workshop experience, and the master-apprentice workshop in design and design application, were the two major western craft education models overlapping the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

8 By 1930, Jensen was employing about two-hundred and fifty silversmiths. Over the decades Jensen designers achieved international reputations. Other independent Danish silver designers today are still revered by Danes, if not as well-known abroad. Some Jensen apprentice-employees opted to open their own studios in Denmark. Others, like Petersen, emigrated to North America, continuing to work in the Danish tradition. Jensen designer Henning Koppel (1918-1981) revealed that organic biomorphic design of the 1940s and 1950s was a specialty. Søren Georg Jensen, Georg Jensen's own son, leaned towards a hard-edge modernism in this same period.

9 American companies also profited from a Danish-silver trend. For example, International Silver produced a popularly-priced version of Jensen's Acorn flatware, designed by Jensen associate Johan Rohde (1856-1935) in 1915, called Royal Danish; Danecraft was an affordable and well-received jewellery catering to the vogue for Danish silver costume jewellery in the 1950s, and the turn to smaller, finely-wrought sterling silver necklaces and the most versatile jewellery accessory: the brooch.

10 When he arrived in Montreal, Petersen was at first employed by Henry Birks & Sons Ltd. as their master goldsmith.5 He then went on his own briefly (1937-39) when he opened a small studio at 2024 McGill College Avenue, to return to Birks in 1939. His career was once more interrupted when silver could not be purchased with the commencement of World War II. Petersen joined the Canadian war effort employed in the manufacture of filters of aluminum and brass wool in demand for World War II Mosquito fighter planes made by the Canadian Wooden Aircraft Company.

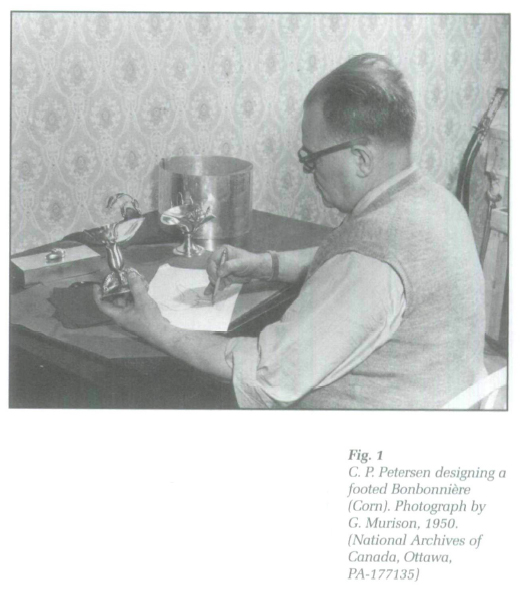

Display large image of Figure 1

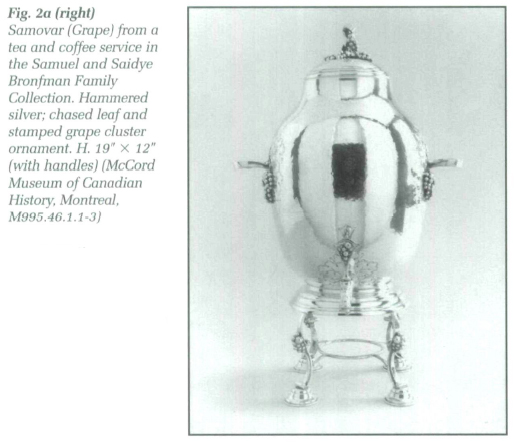

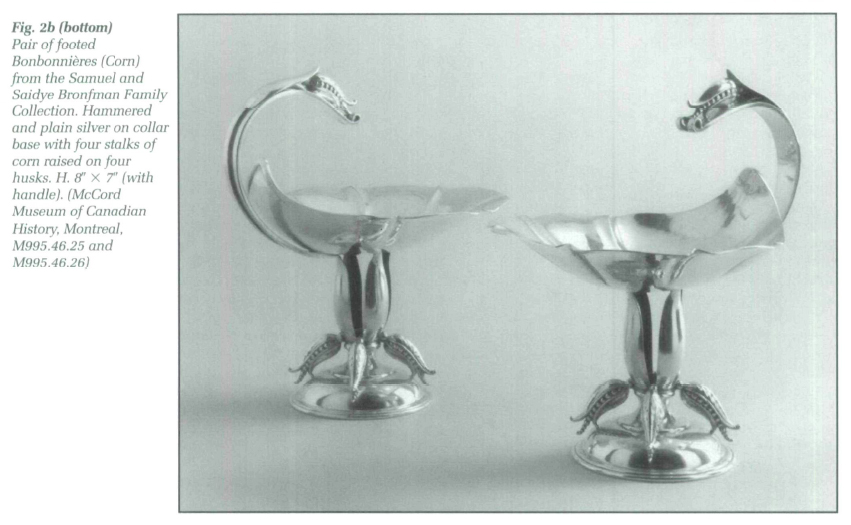

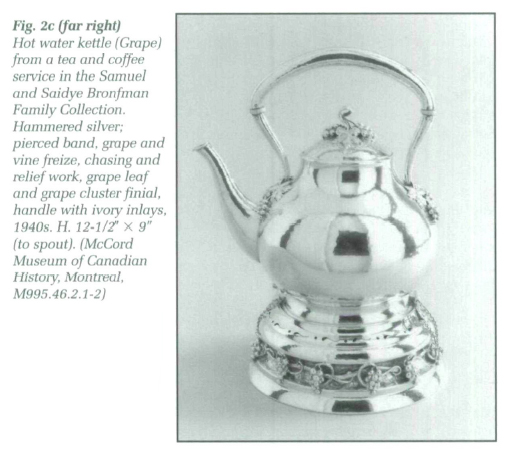

Display large image of Figure 111 Resuming his métier in 1944, Petersen moved to 1221 MacKay Street in downtown Montreal, purchasing a terrace in Prince Edward sandstone, built in 1887 by builder John Buhner, known as the Daniel Stroud house, and later as Lady MacKay's house. He set up shop in the basement, and on the first and second storeys, with a family residence on the third storey (now the Elysée Mandarin Restaurant).6 With the encouragement of the late Saidye Bronfman (1897-1995), wife of the famous Seagram distiller, who took a sincere personal interest in the crafts, Petersen made a greater investment into his trade. Saidye and Samuel Bronfman's first orders were used to establish credit.7 The Bronfmans commissioned family presents, corporate gifts and gifts for recipients of awards for benevolent community and international service work, prompting others to follow suit8 (Fig. 2 a, b, c).

12 C. P. Petersen ran his studio with his sons Arno, John Paul and Ole, who learned the craft from their father as teenagers.9 After the war, C. P. Petersen & Sons handled large orders for Americans as well as Canadians.10 Petersen designs for hand wrought flatware, hollowware, tableware and jewellery, like Georg Jensen's, employed simple, stumpy forms embellished with concentrated passages of ornament, usually fruit, floral or vegetal. Never organic, abstract or conceptual, Petersen designs are typified by the ornamental items of Georg Jensen himself, in the period 1912-23. Petersen was a conservative modernist, and this was expressed in terms of the spare designs he employed for forms. His concession to ornament manifested itself in beautifully-sculpted silver handles or finials for vessels and serving pieces.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 413 Gentlemen's and ladies' silver jewellery was of plain silver, the monogrammed type, or silver set with semi-precious stones (Petersen was partial to opals), as was the Danish tradition. Motifs were often plants indigenous to Denmark or to Canada. One also finds as imagery the bird, scallop-shell, shell-wave-seafoam, pinwheel, the Danish and Canadian wildflower (convolvulus), foliate (the characteristic Danish leaf and bead), foliate-nut form (acorn and hazelnut), hand wrought or in ajouré (pierced work) in oval, round or rectangular format, sold in matching fashionable parures (sets) then stylish, or individual pieces. Petersen also used moulds for the figure, linked to form necklaces or bracelets, co-ordinated with a brooch or screw-back earrings. About two hundred versions of brooches were made, ranging from the naturalistic and stylized types to the personalized monogram varieties.

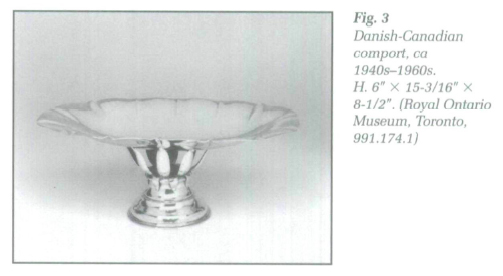

14 Quebec-born householders whose trousseaus were formed in the late-forties to the seventies especially treasure their silver pieces, and kept adding to them faithfully until the company closed. Some Petersen silver has now been handed down to second and third generations in families as gifts or bequests. A few pieces have recently entered Canadian museum decorative arts collections in Manitoba and Toronto11 (Fig. 3). The firm promoted bridal registry flatware and hollow-ware and a registry for boys' Bar Mitzvah and girls' Bat Mitzvah, the latter ritual gaining favour with the Reform denomination.

15 Petersen prices were established to meet the passing trade for a wedding present, a bar or bat mitzvah gift, or a girl's sweet sixteen. Popular gifts for bar mitzvah boys were monogrammed cufflinks, tie clasps, belt buckles, key chains or talus clips for prayer shawls, all with raised initials in diverse lettering selected from a chart.12 Girls might receive a Star of David pendant or perhaps a Chai pendant, the Hebrew word for "life." Judaica was a special focus. Jewish ritual silverware, especially in the ritual Orthodox practice, technically requires at least two services for dairy or meat, and the equivalent for Passover, when kitchen utensils are changed over for the one week of the spring Passover festival. Petersen catered to Jewish culinary practices in that conservative era.13

16 Eleven handmade flatware patterns include Dolphin, Pearl, Wild Berrie [sic], Viking, (modelled after Jensen's Continental pattern of 1908), Old Wood (bevelled and raised at the edges), Vine (the pattern was stamped), Empire, Old English, New Wood (not bevelled, always plain), Modern and Corn, available in plain (satin), high-polish or martelé (hammered) finishes.14 Marks of the planishing hammer deliberately left indicate that a work has been handmade. Old Wood, the most popular pattern, Empire and Old English were designed to accommodate a raised monogram on the handle. Viking, Old Wood, Empire, Old English and New Wood allowed space on the broader part of the handle for an engraved monogram. Petersen silver was especially favoured by Americans because of its greater monetary value due to the difference in the higher price of the American dollar and the tax-free advantage.15

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 517 Petersen flatware service and hollow-ware were coordinated to flatware stock or custom flatware. In addition to being made in standard shapes, hollow-ware was furthermore raised and mechanically spun in a range of graded sizes. Vessels were made of sheet silver with ornament built up and soldered together. They were often raised on plain collar bases or bases chased with anthemion, key-fret borders, bay-leaf garlands or beaded edges soldered to the bowl. Corn and Grape ornament was stamped onto a piece, as was Acorn, Sweet Pea, Lily of the Valley and Cherry, or it might be soldered on, depending upon the desired effect of relief or three-dimension. Ornament was often enhanced by the decoration with niello, a platinum oxide used to cause shadows around an area to highlight the decoration.16 Thus mass production was achieved by means of stamping and spinning.

18 A formulaic approach to production was in many instances the guiding principle; raised monograms for flatware could also personalize men's cufflinks, watch fobs or a belt buckle. In this pre post-modern period, the artist never stated his resolve to raise ecological awareness between culture and nature. Disarmingly simple and as extraordinarily pretty as National Geographic nature documentaries, there was no ironicism intended. Vintage Danish pieces of this era reflect pure nostalgia without kitsch, a rare combination. Neither doctrinal, controversial nor adversarial, Petersen works were strictly representational, not challenging in the aesthetic sense. If a Canadian beaver, beetles, wildflower or fleur-de-lys would appear as lid or handle ornament, the image was never used as double-entendre or metaphor.

19 Petersen flora and fauna struck a direct contrast to Birk's specialty — traditional French and English open-stock Rococo and Neoclassical silver or silver-plated flatware. While Jensen silver was available at Birk's, the prospect of buying Canadian silver appealed to enthusiasts wishing to support local craftsmen, those who showed an actual prejudice in favour of the laboriously handmade, the well-heeled and those of nationalistic bent. His was not a luxury product in the sense that antique silver is; rather it was made to appeal to the bourgeoisie-craft providing a basis for conspicuous consumption. Silver has always had a unique place in the crafts, straddling the world of art, silver and commodity.

20 According to a contemporary account dated 1947, the C. P. Petersen & Sons studio was importing four tons of silver yearly from Johnson Matthey Ltée and employing about twenty silversmiths on the premises.17 There was a hollow-ware specialist, a spinner, polisher, plater, chasers and engravers, jewellers, repairers and tableware specialists. Another half dozen worked on a small farm in eastern Ontario. Petersen trained Canadians, English and Danes for the standard five-year apprenticeship period.

21 The company also handled repair work, contract orders (for Mappins' or Peoples Jewellers for example) and custom work for the replating or redesign of jewellery. A family heirloom could be copied for an additional piece or two, or an object could even be constructed from a photograph a client might produce. The occasional Petersen rococo repoussé tea service or odd pieces that have surfaced, attest to this skill. Other silver techniques were employed on an irregular basis. The firm also made copper and gold work alone or in combination with silver; in addition copper jewellery was also produced. Petersen pieces are not dated; nevertheless, it is safe to say that there was not a continuity of style, and it is homogeneity that characterizes the production rather than heterogeneity. The firm also handled presentation pieces for various institutions, where stock or custom pieces were engraved to order with club and individual name. Pieces were stamped PP STERLING, or PETERSEN HANDMADE STERLING. Petersen's Registered Trademark, the Canadian Lion's Head hallmark was punched to the right of the company's name. The Canadian national mark was inaugurated by the Canadian government under licence in 1934. The capital letters PETERSEN were impressed on flatware in the last twenty years.18

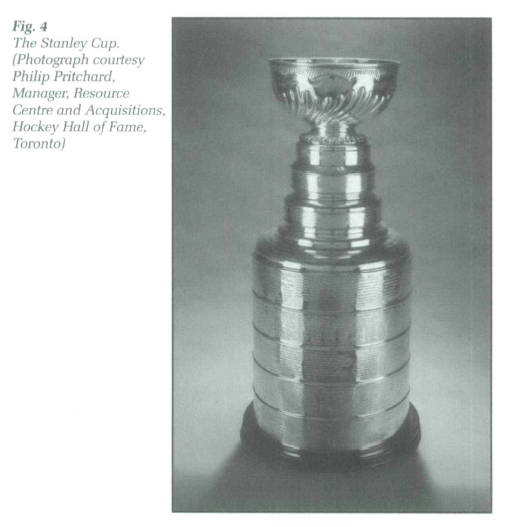

22 C. P. Petersen & Sons is best known for the prestigious and lucrative contract they won for the repair and engraving of the names of teams and players on the National Hockey League's (NHL) Stanley Cup, a trade they established in the late 1940s.19 The Petersen travelling version of the Cup was usually battered by revellers after the winning game, and needed repairing, along with the annual task of engraving of the names of teams and players. In 1962, NHL President Clarence Campbell commissioned Petersen to redesign the Cup after it became too cumbersome. The Petersen Cup is generally kept in the home town of the winning team. Individual Petersen Prince of Wales silver-plated trophies were also made for winning team members.20 Needless to say, Petersen and his wife were great Montreal Canadiens hockey fans (Fig. 4).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 623 As a member of the established Danish religion, Evangelical Lutheranism, Petersen produced a communion set: an inscribed paten in plain silver, an engraved plain silver baptismal bowl, a chalice and small parcel-gilt communion cups in the Danish beaker tradition, which he donated to St. Ansgar's Lutheran Church in Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, Montreal, the church to which he and his family belonged. A community leader, Petersen was president of the Danish-Canadian Society from the middle to late-1940s, during its period of greatest emigration, 1946-48. In honour of its sixtieth anniversary in 1995, the Danish Canadian Society of Montreal published a history of their community, written by historian Rebecca Mancuso.

24 This research report is not meant to be a comprehensive portrait of the man, but of his contribution within a certain context. C. P. Petersen is remembered more for his significant contribution to the silver craft tradition than for innovation, and for a craft that was nourished by the high standards of Danish silver design as it became known beyond Europe in the 1950s. He was active in the age that coincided with the honouring of both art-craft and design in industry. His efforts are contemporary with post-war efforts in the National Gallery of Canada's design centre in Ottawa, initiated by Donald William Buchanan (1908-1966), where important and influential exhibitions, primarily of industrial products, were installed,21 and design exhibitions in Canadian museums and at Toronto's Canadian National Exhibition.

25 The oil crisis of 1973 and the resulting fluctuation in the trade market affected both industry and the crafts globally. The general crisis in the precious metals trade was exacerbated drastically when gold and silver prices rose to unprecedented heights in 1979 when the Nelson Bunker Hunt scandal was uncovered. The Hunt brothers' manipulation of the silver market nearly put them in a position to fix the world price, and the expensive raw material of $50 an ounce troy had to be combined with continuously increasing wages. Many fine Petersen pieces were melted down for the silver. C. P. Petersen had died in 1977. Flatware production at C. P. Petersen & Sons had already stopped by 1969 when the woman trained for this specialty had died. Unable to weather these crises, C. P. Petersen & Sons eventually closed its operations in 1979.

26 The deletion of art-craft from Canadian historic period surveys of Canadian art is a painful reminder of the narrowness of mainstream art history. Even where examples of craft and "high-art" can be compared stylistically, formally and conceptually, few crafts of an era are included and linked as such in catalogue plate illustrations or in museum exhibits. The under appreciation of crafts has a great deal to do with general lack of knowledge of craft and with craft-culture, with academic training, and with the parsimonious disposition in curatorial culture and those who "handle" fine art. The continuing art-crafts debate is still largely about outmoded historical categories and definitions. By contrast, anthropologists, social and material historians have been absorbed more than ever in the story of crafts, the craftsman's role in society, the continuity and preservation of traditions of the "useful" arts, and of the products themselves.

The author would like to thank the Macdonald Stewart Foundation for photography by Giles Rivest that was used in the course of research for this project. Dr. Stephen Inglis aided in the placement of this article and coordinated arrangements to document the Bronfman silver. The organization of access to the Bronfman Petersen silver is due to Franklin Silverstone, curator of the Claridge Collection, who also arranged for study photography by Pierre Charrier. Claridge graciously subsidized the Bronfman-Petersen study photographs. Dr. Martin Bowman, Professor of English, Champlain College, and Scott Bowman, Director of Player Personnel and Head Coach, Detroit Red Wings, advised the author who to contact at the Hockey Hall of Fame, Toronto, concerning the Stanley Cup. Elizabeth Langer put the author in contact with some members of the Danish-Montreal community. Merridy Bradley, Museum Consultant, Canadian Heritage Network, Ottawa, provided the author with a printout of Canadian silver in museum collections. Hideaway Antiques permitted photography of some of their Petersen stock. The author would also like to thank Denise Melanson and Judith Ferlatte who aided in the wordprocessing of this paper.