Articles

From Flag-Waving to Pragmatism:

Images of Patriotism, Heroes and War in Canadian World War II Propaganda Posters

Abstract

During the Second World War, the Canadian government initiated an extensive propaganda campaign designed to bolster morale and convince Canadians of their responsibility to contribute their time, energy and money to the war effort. Posters quickly became an essential element in this program, taking the government's message in full colour "from sea to sea." As cultural artifacts, these posters provide a unique entry point into Canadian society during this era, illustrating how attitudes towards patriotism, heroism and even the war itself shifted substantially between 1939 and 1945. Although the aim of these propaganda posters was to mobilize support for the war effort, the changing nature of their appeals provides graphic evidence that the country experienced three general but ill-defined stages as the war progressed, moving from an initial idealistic flag-waving to a realistic but weary determination to defeat the enemy, and finally, to an idealized vision of peace that promised new heights of consumption and satisfaction.

Résumé

Au cours de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, le gouvernement canadien a entrepris une intense campagne de propagande pour remonter le moral des Canadiens et les convaincre de leur obligation de consacrer temps, énergie et argent à l'effort de guerre. Les affiches sont vite devenues un élément essentiel du programme, proclamant « d'un océan à l'autre » les messages en couleurs du gouvernement. En tant qu'objets culturels, ces affiches offrent une fenêtre unique sur la société canadienne de cette époque et montrent comment les attitudes envers le patriotisme, l'héroïsme et la guerre elle-même ont changé considérablement entre 1939 et 1945. Bien que ces affiches de propagande aient eu pour objet de rallier des appuis pour l'effort de guerre, la nature changeante de leurs messages montre clairement que le pays a traversé trois grandes étapes, assez mal définies, au fur et à mesure que la guerre évoluait, passant de l'étape initiale du patriotisme idéaliste à celle du réalisme et de la détermination à vaincre l'ennemi malgré la lassitude générale et, finalement, à celle d'une vision idéalisée de la paix qui promettait de nouveaux sommets de consommation et de satisfaction.

1 During the Second World War, the Canadian government initiated an extensive propaganda campaign designed to bolster morale and convince Canadians of their responsibility to contribute their time, energy and money to the war effort. Posters quickly became an essential element in this program, taking the government's message in full colour "from sea to sea." As cultural artifacts, these posters provide a unique entry point into Canadian society during this era, illustrating how attitudes towards patriotism, heroism and even the war itself shifted substantially between 1939 and 1945. Although the aim of these propaganda posters was to mobilize support for the war effort, the changing nature of their appeals provides graphic evidence that the country experienced three general but ill-defined stages as the war progressed, moving from an initial idealistic flag-waving to a realistic but weary determination to defeat the enemy, and finally, to an idealized vision of peace that promised new heights of consumption and satisfaction.1

2 Canadians were unprepared for war in 1939, despite the events of the preceding year that, in hindsight at least, clearly foreshadowed the outbreak of hostilities. In military terms, all of Canada's forces were under-strength and ill-equipped. The Army stood at 4 261 permanent members, backed by a partially trained militia of 51 000.2 Its equipment was obsolete and supplies were in such short supply that recruits who signed up in September had to make do without uniforms and, on occasion, rifles.3 The situation was much the same for the Navy and the Air Force. The Navy's regular force numbered under 2 000 and its fleet consisted of four modern destroyers, two older ones, and four minesweepers. The Air Force consisted of eight squadrons of 3 048 men, and, although it had 270 aircraft, "only 37 were even remotely combat-worthy."4

3 This inadequate military preparation was matched by a similar psychological position. Having just begun to recover from the trauma of a severe ten-year depression that had strained the country's religious, social and political institutions and bred widespread cynicism and anger, Canadians were reticent to assume the responsibilities and sacrifices demanded by war. Although they were aware of the deteriorating situation in Europe, many Canadians continued to hope that a full-scale conflict could be averted. When it became obvious that war was inevitable, politicians and citizens talked of limiting Canada's participation; many English Canadians preferred to "get on with the job of building a North American nation," while French Canadians feared they would, once again, be subjected to conscription.5 So widespread were these attitudes that a prominent member of the cabinet later remarked that the "country was 75% isolationist at the beginning of the war."6 In sharp contrast to the jubilation and patriotic fervour that had marked the commencement of World War I, Canadians greeted the declaration of war in September 1939 with somber reluctance.

4 This lack of preparation and enthusiasm, coupled with the large-scale sacrifices required by "total war" made it imperative that the government defuse discontent and mobilize public support for the war effort. Recognizing that this conflict was "a war of the mind and spirit as well as a war of manpower and weapons," the Canadian government undertook an extensive propaganda campaign to inspire patriotic feelings, boost morale, provide information and solicit support for salvage and anti-sabotage campaigns.7 Posters played a significant part in these campaigns. Because the government's most immediate concern was to recruit manpower and raise money, the majority of the posters focus on these issues. Aiming their messages primarily at the homefront, these posters addressed civilians whose role was aptly described by the contemporary phrase, "the man behind the man behind the gun."8

5 The importance of posters in the government's campaigns to stimulate support for the war effort can be attributed, at least in part, to their physical properties: they were relatively inexpensive to produce; they could be created, printed and distributed in a relatively short period of time; and they enjoyed a broad, sustained exposure. This exposure was particularly important during this wartime period when it was reported that, on average, "only 10% of the workers read a daily newspaper."9 The popularity of posters as a propaganda tool, however, was also a consequence of the manner in which they sent their messages. By using images as a form of visual shorthand they implied much more than was actually stated or shown. Making this visual shorthand graphic through "vigorous composition, eloquent colour, an unambiguous theme [and] impassioned execution," posters communicated complex, highly emotional messages "in the blink of an eye."10

6 Because the powerful messages posters can transmit tend to be instantly internalized rather than analyzed, they can have a strikingly immediate impact on people's attitudes, values and aspirations.11 To be successful, however, this act of communication must utilize more than shapes, colours, titles or captions. It must play upon cultural norms and symbols that are instantly recognizable to the viewer, elements that cultural critic and semiotician Roland Barthes has identified as the cultural or referential code.12 It is this element of the poster that invites historical investigation.

7 Because posters must tap into and exploit commonly held values and beliefs to be successful, they can be seen as cultural artifacts, providing graphic evidence of attitudes, beliefs and values of the time. But these posters are more than the visual records of changing public opinion. They were, in fact, active agents in this process of change. As part of society's cultural resources, the images used in these posters influenced the way society made sense of the social and ideological upheaval caused by the war. For, as Eric Leed has shown, people often draw upon "the cultural repertoire of meaning...to define felt alterations in themselves."13

8 Relying on the impact, immediacy, emotional appeal and sustained exposure of posters, federal government ministries and agencies under the guidance of the Wartime Information Board produced approximately 700 propaganda posters aimed at recruiting manpower, mobilizing financial resources, bolstering morale and encouraging participation in salvage and anti-sabotage programs.14 Ranging in size from the 92 X 122-cm (36 X 47.5-inch) poster used on hoardings and small billboards, through the mid-sized 45 X 60-cm (17.5 X 23.5-inch) posters displayed in schools, government offices and shop windows, to smaller renditions that appeared on buses and streetcars, and miniature reproductions that were used as counter cards, envelope stuffers15 and matchbox covers,16 the posters saturated the nation's cities and towns, and quickly became familiar to most Canadians.17

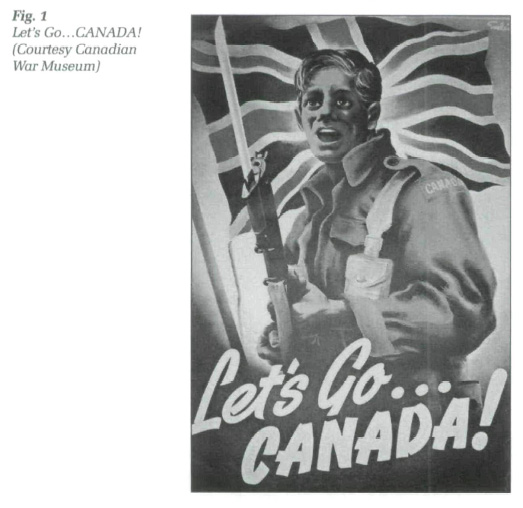

9 At the beginning of the war, when public support for the war was less than enthusiastic, poster campaigns tended to idealize war by mounting emotional appeals that cast patriotism in terms of the flag and an implied moral authority. "Let's Go...CANADA!" (Fig. 1) is a good example of this approach.18 Here we see a clean-cut youth in army uniform, rifle and bayonet grasped firmly in his hands, standing in front of a gently waving Union Jack, the diagonals of which radiate from his head like a kind of halo. Painted with vibrant colours, marked contrasts19 and strong diagonals, the oddly vulnerable young soldier represented here is both heroic and moving. Yet even with the halo effect which alludes to God's protection and a "holy" responsibility being fulfilled, and his brightly lit bayonet thrust upwards out of the picture like a shaft of light, the soldier's young face is stamped with concern and vulnerability. As he stares ahead bravely, shouting encouragement to those who would follow, he seems to embody Mackenzie King's assertion that the war was "a crusade to save Christian civilization."20 Wrapped in the flag, this youthful hero, who looks as though he had grown up reading the Boy's Own Annual, exemplifies duty and personal moral responsibility. Although these sentiments may have been more reflective of Canadians' attitudes towards war and patriotism in earlier conflicts, they were the values the government wished to encourage as they attempted to recreate Canadian responses to World War I. But the war alluded to in this poster is romanticized and unspecific. The enemy is not identified or even referred to, except in the most indirect fashion, and there is no fighting in this image. Even the caption, presented in an informal mix of pseudo-handwriting with bulky capital letters, is ambivalent. Redolent of a sporting event rather than a war, the injunction "Let's Go...CANADA!" begs the question, where or why.

10 While it may be difficult to decide if "Let's Go...CANADA!" was designed as a recruiting or a Victory Bond poster, "CANADA'S NEW ARMY NEEDS MEN LIKE YOU" (Fig. 2) is clear and focussed in its goal.21 Created and produced during the earlier years of the war as the government attempted to counteract low morale, this poster uses the glory and grandeur of myth to promote recruitment. Linking the past with the future — a lief-motif of government propaganda that was articulated during this period22 — this poster shows three soldiers on motorcycles; the one in the foreground "doing a wheelie" as he races across the desert sand towards some unseen goal, the other two mimicking this action to varying degrees. In the background, rising majestically over the motorcyclists and echoing the pose of the foremost soldier rides a "knight in shining armour" astride a rearing stallion. Gleaming white against the vibrant blue sky and larger than life, the knight is easily recognizable as one of King Arthur's legendary Knights of the Round Table, and, as such, conjures up images of chivalry, courage and self-sacrifice. By equating the soldiers with the knights of old, the poster implies that the virtues of chivalry, such as honour and dedication, could be claimed by prospective recruits who volunteered to fight in a Crusade against the faithless infidels. This imagery, then, suggests that the war was a noble contest of right versus wrong, a struggle fought with valour and courage on the part of Canada's army. An unspoken but nevertheless important corollary was its association of speed, excitement and adventure with the war. Here again, as with "Let's Go...CANADA!," there is no real war present — no blood, no violence, no brutality. In fact, aside from the knight's drawn lance, there are no weapons and no enemy either depicted or referred to. The appeal is to an idealized vision of war, neatly sanitized and couched in mythic terms — a conceit that was relatively easy to maintain in the early stages of the war while Canadian troops had few encounters with the reality of war.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

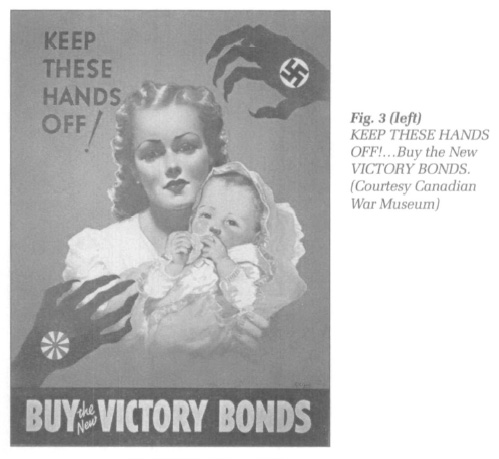

Display large image of Figure 311 By 1942, these generic appeals to a distant and unreal vision of war had largely disappeared, in part because the government was concerned that "the people did not have a sense of urgency... [and were] not fully aware of the dangers."23 "KEEP THESE HANDS OFF!.. .Buy the New VICTORY BONDS" (Fig. 3) is a good example of the new approach that began to appear.24 Here we see the head and shoulders of a beautiful young woman cuddling an adorable, chubby baby swaddled in a no doubt sweet-smelling pink blanket. Set against a sky-blue background, both mother and child are dressed in white. There is, however, a jarring note in this idyllic image. While the baby seems contented and happy, the mother, made up in contemporary Hollywood style with pencilled eyebrows and a full, luscious mouth, beseeches the viewer with haunted, fearful eyes. The source of her concern is obvious: this Madonna and Child are threatened by two large, dark, sinister hands that hover menacingly in opposite corners of the poster. With long, vicious nails, these claw-like hands actually encroach on a portion of the image, groping towards the baby and the woman's breast. To ensure that the viewer does not overlook the implication of these images, the claws are clearly labelled, one with a swastika, the other with a rising sun insignia. By melding religious and cultural elements and tapping into the highly charged sentiment surrounding both the ideal of domesticity and the Madonna and Child, this image used some extremely powerful myths to motivate Canadians.

12 With this image, posters began to acknowledge the reality of war, alluding to the potential threats to the civilian population. At this point Canada's enemies are identified and the message is clear: women and children are threatened by both Nazi and Japanese fascism, and must be protected. And, through its exhortation to "Buy Victory Bonds," this poster attempts to enlist everyone in the role of protector. Now the elements of patriotism are becoming more concrete. Instead of vague appeals to flags or chivalric myth, patriotism is now cast in terms of protecting defenseless women and children from clearly defined and easily recognizable threats. Despite appeals that would be dismissed today as exploitive, transparent and almost maudlin, at the time of its release this poster was extremely effective and, according to observers, had a significant impact on the war effort.25 In fact, in a survey that was commissioned to evaluate the effectiveness of various types of posters, "Keep These Hands Off!" was judged to be the "most successful."26

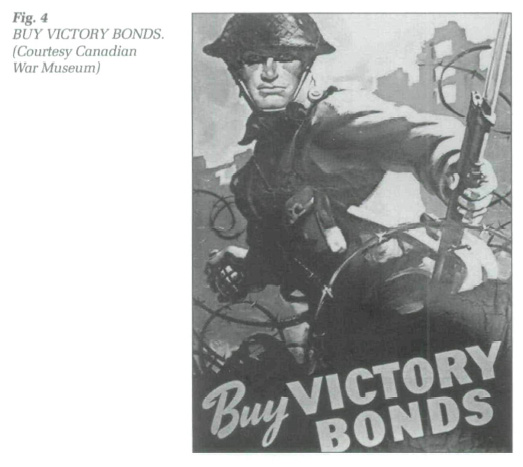

13 While posters alluding to the homefront remained largely generic and free of actual representations of blood and injury, they did at least in part begin to acknowledge the reality of war. Recruiting posters exhibited the same tendencies as Canadians became increasingly interested in "licking the daylights out of Germany."27 Moving away from the images of mythical combatants and soldiers "wrapped in the flag," posters like "BUY VICTORY BONDS" (Fig. 4) purported to show actual fighting. Here we have an infantryman, rifle grasped in his left hand, poised to lob a grenade right out of the poster towards an unseen enemy. Dramatically lit from the top and the side by a flash of white light, presumably from an explosion, the soldier, clearly labelled "Canada" by his well-illuminated shoulder patch, is completely ringed by coils of black barbed wire glinting nastily in the bright light. Behind him, flames and the red-orange shells of bombed-out buildings attest to the heat and destruction of Allied bombs and artillery. With strong contrasts and vivid colours, this image conjures up the destruction of war. Yet, the soldier is still an idealized figure. Surrounded by all this dirt and destruction, his uniform appears clean and pressed, his helmet sits straight on his head and his hands and face are spotless. Like the stereotypical comic book soldier, his handsome unravaged face with its square jaw, the determined set of his mouth, and his strong fighter's nose, conveys the impression that this solitary hero, the incarnation of courage, could hold his own against any enemy, regardless of the circumstances. Although he exudes a somewhat comforting message of strength and courage, the soldier also hints at the dark side of war. For, like the masculine war machine portrayed in the famous and highly stylized German poster "Und Du?," the soldier's helmet has thrown a dramatic shadow across his face, partially obscuring his steely eyes. And, unless he changes his aim, he is going to lob the grenade dangerously close to the viewer. With that in mind, the boldly written exhortation, "BUY VICTORY BONDS," can be seen to take on a new twist. However, this prize-winning poster appeals mainly to our collective pride in the heroic dimensions of war and commands our continued support for its demands.

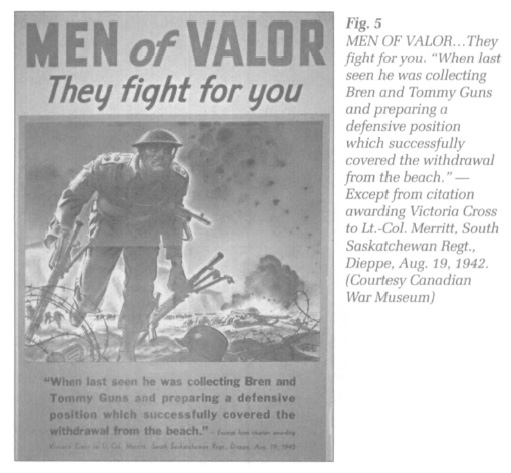

14 Hubert Roger's "Men of Valour" series attempted to bridge the gap between the mythic hero and the new reality by focussing on Canada's real heroes. With the caption "MEN OF VALOR...They fight for you" (Fig. 5), this series portrayed the courageous actions that earned these men the Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Service Cross or the Distinguished Service Order along with brief excerpts from their citations. Roger's representation of Lt.-Col. C. C. Merritt's experience on the beach at Dieppe is a particularly striking example. Here we see Merritt in the heat of battle, valiantly running through coils of barbed wire to collect the Bren guns of his fallen comrades in order to organize a defensive position to cover the withdrawal from the beach. Under his helmet and the heavy sky that seems to press him towards the ground, his face and neck are straining forward with exertion, his mouth is pulled down in a grimace, and his eyes blaze with determination. With his own officer-issued Thompson submachine gun wedged under his arm, he carries two other guns he has collected, one in each hand. Immediately in front of him, looming large in the forefront of the poster, lies a German helmet and under his feet the distinctive German cylindrical gas-mask container — implying a dead or seriously injured enemy. The pressure and uncertainty of battle, as well as the courage and determination of Canadian troops are obvious from the confused scene behind him: a group of men caught in open territory run for cover, a prone soldier fires valiantly while in the background a bright explosion creates a plume of black smoke. Throwing a pall over the entire scene is the muddy, red-brown, smoky sky that almost conceals the cliffs rising sharply to the rear. Eerie and depressing, this dried-blood colour permeates the entire image and is echoed in the caption, "MEN OF VALOUR.. .They fight for you." Yet despite its emotional content and the assertion that these men "fight for you," the poster makes no explicit demands. Instead, it graphically demonstrates the stark dimensions of the sacrifices at Dieppe and war in general — the dirt, pain, courage and death — and lets the viewers' consciences be their guide. With this poster series, the earlier pristine and relatively sanitized vision of the war began to recede. However, although this image is more realistic about the demands of war than earlier ones, it continues along the well-worn path, casting heroism and patriotism in terms of fearless, solitary heroes battling insurmountable odds.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

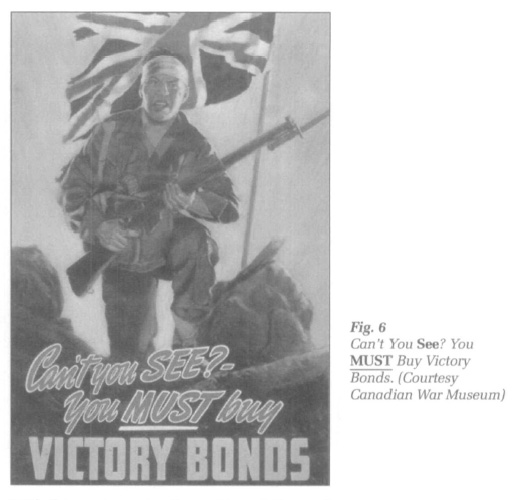

Display large image of Figure 615 As the war dragged on, the government was repeatedly apprised of the necessity to show "how long and how grim"28 the war would be; posters became almost strident in their representations of the hero. "Can't You See? You MUST Buy Victory Bonds" (Fig. 6) aptly illustrates this change. Here we see a soldier down on one knee firing a Bren-like gun which is mounted on an extended tripod. Shells blaze from its muzzle. With his left hand he holds aloft the Union Jack, which flutters behind his head. In the distance, a tank is rumbling toward him, while some distance back an explosion illuminates the rubble of some buildings and stains the canary-yellow sky with black smoke. By portraying a solitary soldier in the midst of battle and by using the flag as a central element of the composition, this poster invites comparisons with both "BUY VICTORY BONDS" and "Let's Go...CANADA!," but it is clearly a different soldier and a different flag. Where the immaculate hero of Figure 4, calmly lobbing a grenade, seems to have escaped the fear, disorder and noise of war, the soldier represented here is under attack; his uniform is dirty and torn, his face, clearly visible under his helmet, is twisted into an anxious yet determined grimace, and he is firing furiously. The flag has undergone a similar transformation. While in "Let's Go...CANADA!" the flag is a perfect, unsullied specimen, the Union Jack fluttering bravely above this soldier is tattered and torn. In spite of its ragged condition, however, the flag and the way it is displayed bears a marked resemblance to the standards used in the Crusades. The caption, written in white pseudo-handwriting against the dark foreground also attests to a change in tone and approach. "Can't youSee?" it demands almost confrontationally, "You MUST Buy Victory Bonds." The implication is that those on the homefront, in contrast to those who had seen the horrors of war, needed heavy-handed pressure to convince them to contribute. Despite this move to abandon a number of the earlier conceits and to acknowledge some of the realities of war, a number of anomalies in the poster undercut this movement. For example, the tank moving up in the background bears a strong resemblance to tanks used in WW I, not the conflict underway at the time of the campaign. And the soldier himself, although ostensibly portrayed in the middle of an actual battle, is beleaguered, out of position and firing skyward instead of at the enemy. In addition to these curiosities, this image also continues to exhibit at least traces of the earlier approach; it does not portray or identify the enemy, focusses on the solitary (although now beleaguered) hero, and accords prominence to the flag which is held aloft like a knightly standard.

Display large image of Figure 7

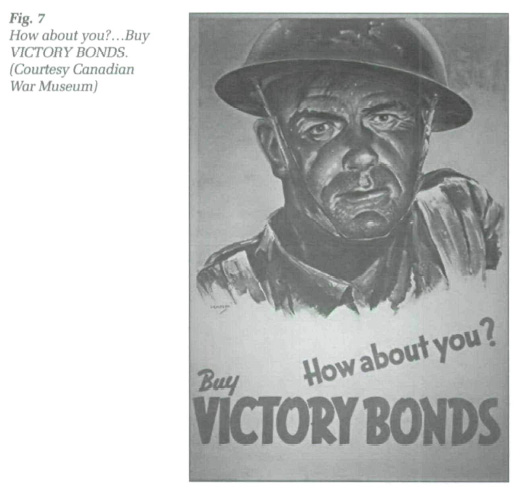

Display large image of Figure 716 As Canadians saw their troops committed to the day-to-day struggle in Sicily and Italy, they began to develop a more realistic attitude toward the war. In response, the majority of recruitment and bond posters moved away from traditional images of the hero, whether mythic or realistic. "How about you?...Buy VICTORY BONDS" (Fig. 7) epitomizes this new approach. Set against a washed-out buff background, this poster shows the head and shoulders of a real soldier — helmet pushed awkwardly back on his head, hair plastered to his forehead, uniform streaked with dirt, and his face unshaven and beaded with sweat. Unlike the pristine symbolic figure in "BUY VICTORY BONDS," this soldier looks as if he has actually experienced combat, and the face that looks out at us is hauntingly human, with uneven, imperfect features. Lit from below to emphasize the tired but intent lines of his face, this image punctures the myth of war as a glorious and noble experience and reveals instead something of the harrowing conditions of soldiers facing death. In contrast to the heroic infantryman in Figure 4, whose mouth is set in a determined line and whose eyes are obscured by shadow, this soldier's eyes attract our attention by staring directly and beseechingly out of the poster. His mouth, open and slightly askew, seems to be appealing for help — an appeal that is accentuated by the awkward slope of his shoulders as he earnestly leans towards us in his ill-fitting collar, which emphasizes his vulnerability. This soldier is not the one-dimensional hero figure of earlier posters. There is no flag here, no dramatic colours, no strongly contrasted lighting and no weapons. Instead, we see a vulnerable soldier, exhausted and perhaps even fearful, yet determined to do his duty, even as he wonders if those on the homefront are doing theirs. How about you?, he asks the viewer. Confronting the ambiguity of war — the dirt, pain and suffering, as well as the duty, integrity and sacrifice — this soldier is acutely aware of the possibility that he may have to die for his country. Although his situation is not invested with the facile glamour pervading earlier posters like "CANADA'S NEW ARMY" (Fig. 2), he remains steadfast in his determination to do his duty and, if necessary, make the supreme sacrifice.

17 In these last two posters, the concepts of heroism and patriotism have moved beyond the shallow elements of flags, myth and bravado shown in the earlier posters and taken on a more complex hue. Now heroes are represented as having been initiated into the terror and brutality of war, yet determined to continue fighting. The elements of patriotism have shifted too. No longer framed in terms of the flag, adventure or the grandeur of earlier contests, patriotism now involves a measured and somewhat reluctant acceptance of dedication and duty in the face of war's grim realities. Linking the war with the homefront, this poster and others like it explicitly enlist not only the soldiers but all Canadians in the war effort.

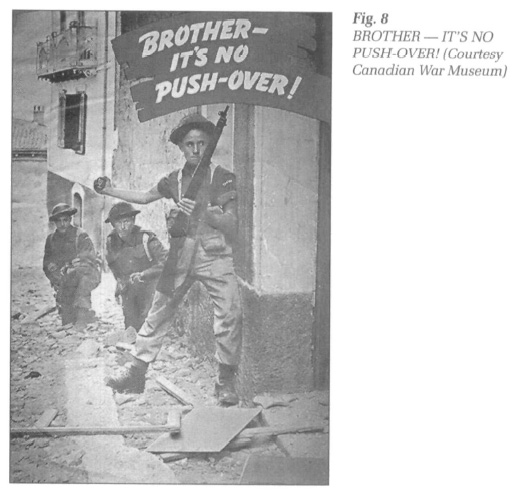

18 By the beginning of 1944, after Canadians had seen the death and destruction of the Italian Campaign splashed across the front pages of their newspapers, the "mind benders"29 were able to convince the government that emotional exhortations to patriotism, duty and sacrifice could not sustain the day-to-day sacrifices and deprivations the war exacted. Taking a tact they had been discussing since mid-1943, they began to "swing away from the heavy, patriotic, emotional appeal."30 Posters began to reflect the true dimensions of the contest and to offer a markedly different concept of the hero. "BROTHER — IT'S NO PUSH-OVER!" (Fig. 8) uses a harsh photograph taken by a wartime correspondent rather than the usual artwork to depict the grim reality of house-to-house combat in Italy.31 It shows an amazingly young-looking infantryman as he edges his way along the front wall of a house. With one hand poised to throw a grenade into the doorway, his other hand holds his rifle upright, partially obscuring, yet drawing attention to, his face. Although his youthfulness encourages us to see him as the boy next door, his face and demeanor distance him from the vulnerable youth in "Let's Go...CANADA!" (Fig. 1). With his shirt-sleeves rolled up and his helmet pushed back on his head, he projects the image of the street-smart, ethnic soldier that was popularized by American films of the era. Confident, perhaps even cocky, this fighter seems in control of a difficult situation, although he is supported by two riflemen who crouch behind him, ready to deal with enemy reactions after the grenade is thrown.32 The street at his feet is littered with rubble from the day's fighting, and, in the background, a window with shutters and a small, wrought-iron balcony stand as a poignant reminder of happier times when the narrow street would have been thronged with life as women hung out their wash, children played in the street and men sat on the balcony, enjoying their after-dinner smoke. Against the grainy black and white of the photograph, the caption, "BROTHER — IT'S NO PUSH-OVER!," is printed in bold capital letters set against a background of red that looks both makeshift and rushed, as if it had been brushed on with a single stroke. Here, this poster argues, is the reality of war and those who fight it. No longer seen as centring on chivalry and daring, the core of heroism is now represented as the dauntless spirit of resolution which is summoned to meet each menacing situation and the slogging determination to get the job done. Heroes are ordinary joes anxious to get the job finished and come home.33 It is interesting to note that viewers are not exhorted to buy bonds or to enlist; as with the "Men of Valour" series (Fig. 5), their reaction is left to their own conscience. Implicitly, however, both the soldiers' sacrifices and the immensity of their jobs encourages Canadians to join forces because "it's a tough job and someone's got to do it."

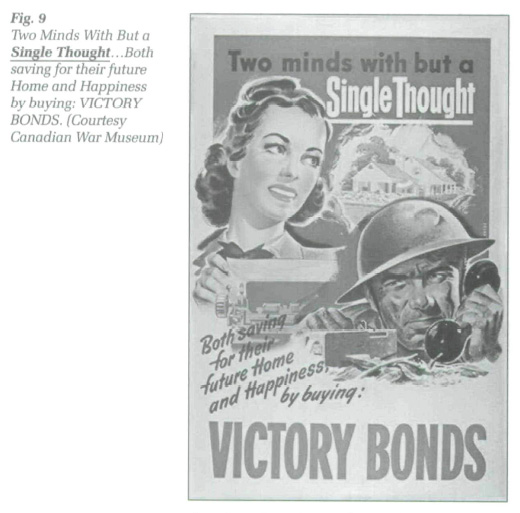

19 Victory Bond posters of this period embody another aspect of this strategy shift. Like "BROTHER —IT'S NO PUSH-OVER!" (Fig. 8) the bond posters at this stage of the war also abandoned sentimental appeals to patriotism. Instead of showing gritty images of war and sacrifice, they began to emphasize "self-interest" and focus on what the publicity men called the "hopeful, forward-looking side."34 "Two Minds With But aSingle Thought... Both saving for their future Home and Happiness by buying: VICTORY BONDS" (Fig. 9) aptly illustrates this approach. Featuring the smiling faces of a perfect young couple, separated by the war yet united by their concerns and plans for the future, this poster implicitly links peace and prosperity to the efforts of civilians and the armed forces. The woman, a brunette with softly waved hair who bears an amazing resemblance to the "Ponds girl" of advertising fame, appears top left, seated at her typewriter, rolling in a piece of paper. She is ignoring her office work temporarily and is gazing dreamily into the distance. Her husband is a handsome, take-charge man with strong features and large, capable hands, presumably serving on the battlefields of Europe. His face, smudged with grime and covered in a day's stubble, is bathed in a light sweat as he hunches over the field telephone, talking urgently. However, although his jaw is set in determination and his eyebrows knit together with concern, he eyes and mouth exude an air of confidence. Unlike the hard-pressed soldier in "How about you?," this man believes that victory is within reach and, secure in that knowledge, he can afford to take a minute or two to fantasize about his hopes for the future. The point of contact for this couple is their dream of the future — a beautiful, spacious white house. Modern and almost pretentious, their vision is very different from the cozy "cottage for two" that was a staple in so many popular songs of the day, or even the modest housing that was promoted in the government's post-war reconstruction propaganda. Dreamlike and almost gleaming in the rays of sunlight, it sits on an ample lot in the suburbs, and sports a large red and white umbrella to shade the side patio, large profusely blooming flower beds along the side of the property and a new car in the driveway. All that is missing is a white picket fence. By linking a civilian woman with her soldier-husband and pointing out that they are "both saving for their future home and happiness by buying Victory Bonds," the poster implies that this is a dream that both combatants and those on the homefront can share. This message was particularly potent at a time when public opinion surveys advised of growing resentment between war-weary civilians and the armed forces. While attempting to undermine this potential rift, this poster promotes the purchase of Victory Bonds as the key to future security, and holds out post-war gratification for all. In doing so, it recasts visions of the war and alters the concept of patriotism. The earlier emphasis on the idealized war, and the later desperate plea to "get the dirty job done" has given way to an idealized vision of peace. In response to that shift, war takes on the guise of a phenomenon which, for all its horrors, can have a positive outcome. Patriotism begins to undergo a similar revision. While buying bonds had previously been promoted as a patriotic duty, now it was seen as a wise investment in the future. No longer equated with the duty to support the troops in the field, defeat the enemy and make the world safe for democracy, the purchase of Victory Bonds became nothing more than a cog in the wheel of post-war prosperity. With this decisive change, patriotism began to shade into consumerism and the war itself began to set the stage for the post-war boom.

Display large image of Figure 9

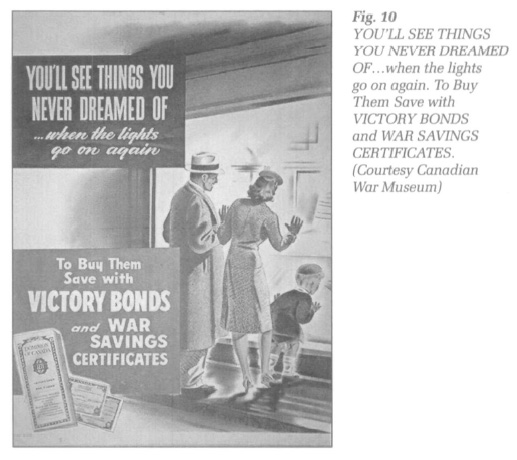

Display large image of Figure 920 "YOU'LL SEE THINGS YOU NEVER DREAMED OF" (Fig. 10) makes this message even more graphic. Here we see a well-dressed, middle-class family of three — husband, wife and young son — gazing raptly into a full-length store window. Like the radiant light that streams from a religious artifact, bright, golden light pours from the display, illuminating both the darkened street and the awestruck family tableau. Mother and son lean intently toward the alluring scene; while the boy actually presses both his hands and his nose against the window, the mother is more restrained. But she, too, leans her hands against the window as she inspects items on the other side of the display. Although the father is less engaged with the display, he seems to be talking proudly with his wife as they both examine the merchandise and make out their wish list. The display, although fragmented and incomplete, conveys the impression of gleaming modernity with slick, clean lines. Playing on years of deprivation and sacrifice, this image holds out the dream of post-war prosperity and shows how all members of the family will find things to satisfy them. The caption, exploiting the longing and desire embodied in the era's poignant popular music, promises these consumer goods, and the implicit return to normalcy, "when the lights go on again."35 Yet by linking post-war normalcy with consumerism, the government was actively reworking this notion, capitalizing on the title of the song while ignoring the idea it espoused. The lyrics of the song celebrate "how sweet and simple life can be...when the boys are home again...[when] a kiss won't mean Good-bye but Hello to love...and we'll have time for things like wedding rings."36 To ensure that their message of consumption has been received, the text, highlighted on a red square that overlay's the image to some extent, instructs, "To Buy Them, Save with VICTORY BONDS and WAR SAVINGS CERTIFICATES." With victory close at hand, then, images of the war, soldiers, and sacrifice, whether idealized or realistic, disappear from the posters. Reacting to concerns about post-war reconstruction revealed in contemporary public opinion surveys,37 government propaganda began to define the "return to normalcy" in terms of consumer goods. As a result, Canadians were encouraged to buy Victory Bonds not as a patriotic activity to support the war effort or to fund reconstruction, but to save for the consumer society that awaited them after the armistice.

21 Although posters were numerous, widely distributed and graphically impressive, it is difficult to ascertain the impact they had on the attitudes and actions of Canadians. Just as writing intellectual and cultural history "is like trying to nail jelly to the wall," attempting to gauge response to cultural artifacts is a difficult and taxing matter.38 One can, nonetheless, advance some propositions concerning the posters' efficacy. The first and perhaps most telling point is that advertising men, whose business it was to understand and employ the mechanics of persuasion, consistently used posters as an integral element in their campaigns.39 Reminiscences from the period also provide some insight into the posters' impact, showing that specific posters did have a significant effect on individual viewers, sharpening their dedication to the cause.40 Finally, the phenomenal success of the recruiting and Victory Bond campaigns attest to the effectiveness of these advertising campaigns. Despite the country's reluctance to become involved, by the war's end 1 086 343 men and women performed active full-time service in the three services, while 1 239 327 worked in wartime industries.41 Financial contributions were equally impressive: the 11 Victory Bond campaigns raised more than 12 billion dollars, or more than $200 per year for every man, woman and child in the country.42

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1022 During the war, Canadians were continually bombarded with government propaganda posters urging them to conserve, contribute, donate, defer and, in general, reorganize their lives to support the war effort. These posters, particularly those created for the recruiting and Victory Bond campaigns, provide a valuable opportunity to examine the nature of the appeals and their transformation as the war progressed. By examining the way the focus and nature of the posters shifted during the war, we can explore the government's perception of popular attitudes, and its assessment of the most profitable method of exploiting them to maximize public support for the war. The posters explored above reveal that, during the first two years of the war, Canadians were presented with an idealized vision of war that cast patriotism and heroism in terms of flag-waving and myth. Later, as the nation came to acknowledge the bloody reality of war and the enormity of the sacrifices demanded, poster images became more realistic. At this juncture, they portrayed the exhausted but determined soldier as the hero and the supporting civilians as patriots. During the last year of the war, these concepts shifted again. As confidence in the inevitability of victory grew and the population began to look forward to the war's end, images of soldiers disappeared from the posters and patriotism became connected with saving money to support post-war consumerism. By shedding light on the changing attitudes Canadians held towards the war, patriotism and heroism between 1939 and 1945, these posters help, in the familiar terminology of the Annales school, to illuminate the nature of Canadians' wartime mentalité.

This research, and the larger work of which it is a part, has been supported by a fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.