Articles

A Unique and Important Asset?

The Transfer of the War Art Collections from the National Gallery of Canada to the Canadian War Museum

Abstract

In 1971, most of Canada's First and Second World War art was transferred from the National Gallery of Canada to the Canadian War Museum. The approximately 6 000 paintings transferred included works by members of the Group of Seven and current luminaries like Alex Colville. There are a number of reasons for the timing and occurance of the transfer, preeminent among them the then - intellectual dominance of modernism in art circles. Most of Canada's war artists worked in figurative styles, then seen as anti-progressive and associated with the forces of reaction.

Résumé

En 1971, la plupart des œuvres d'art cana-diennes inspirées de la Première et de la Seconde Guerres mondiales ont été transférées du Musée des beaux-arts du Canada au Musée canadien de la guerre. Au nombre des quelque 6 000 tableaux ainsi transférés figurent des œuvres de membres du Groupe des Sept et de célébrités du moment, comme Alex Colville. De nombreuses raisons ont dicté ce transfert, ainsi que le moment où il a été effectué, la plus importante étant la domination intellectuelle du modernisme dans les cercles artistiques de l'époque. La plupart des artistes de guerre canadiens avaient en effet opté pour des styles figuratifs, considérés dans les années 70 comme réfractaires au progrès et associés aux forces réactionnaires.

1 War art is not always considered art. Depending on the political and cultural context of any historical period, war art is either fashionable or disdained. As well, at various times, different and often very subjective tastes have determined which pieces qualify as art. Even more curiously, war art by artists who at other points in their careers are important figures is not guaranteed a place in an art museum.

2 Different countries view matters differently. At the basis of their determination of whether war art constitutes art are political and above all, cultural considerations. Political considerations often determine the practice of collecting, especially in public institutions, which ultimately has an effect on the production of art. For example, the British government discouraged the production of grand battle painting at the beginning of the 19th century because their archenemy at the time, Napoleon, had so obviously supported its production. Large-scale military compositions were not commissioned, and consequently none were available for exhibit. In the visible absence of such work, the result was that no market developed for it.1

3 There have always been differences between the treatment accorded official war art and that given non-official war art. When war art of the official kind has been produced, countries have dealt with its future in diverse ways. In Britain, Lord Clark, then Sir Kenneth Clark, divided up the art of the Second World War between art galleries (which received what was deemed "art"), and the Imperial War Museum (which was given art that was deemed "documentary"). In the U.S., Second World War art is housed in often appalling conditions with the different services and none but the military see it. The Germans have only recently repatriated their official Second World War art from the U.S., and it languishes, barely documented, in a small town in Bavaria. The war art of the Japanese ended up in the Tokyo Museum of Modern Art. Australia has deposited all their war art in a splendid purpose-built memorial building. In New Zealand, the war art was transferred from the National Gallery to the National Archives.

4 Our own National Gallery of Canada finds non-official war art by artists from outside of Canada such as Otto Dix or Kathe Kollwitz eminently collectable. It has less interest in Canadian official war art, and indeed, in 1971 chose to divest itself of much of the military art produced by its own artists under the official war art programs of the two world wars, the Canadian War Memorials Fund (Fig. 1) and the Canadian War Records. This work was transferred to the Canadian War Museum. The circumstances surrounding this event shed light on some of the cultural and artistic concerns at play in the Canadian art world during this period.

5 The War Art Collections now in the Canadian War Museum consist largely of two groups of work. The First World War art numbers just over 1 000 pieces. The brainchild of Lord Beaverbrook (then Sir Max Aitken), a Canadian-born entrepreneur, newspaper magnate and British cabinet minister, this collection was established during the First World War. Artists from a number of allied countries, working both in traditional and avant-garde modes, were commissioned to depict the Canadian experience in the field and to complete large canvases for a War Memorial building in Ottawa that was proposed but never built. These artists included such highly regarded British artists as Augustus John, and up-and-coming Canadian artists like Frederick Varley and A. Y. Jackson. The deliberate selection of artists of note, and the hiring of the well-known art critic of the time, Paul Konody (who had a marked proclivity for the avant-garde), to advise, indicates clearly that Lord Beaverbrook intended the collection to function as art. Certainly, the plans devised by Beaverbrook and his committee for the War Memorial building in Ottawa are more suggestive of an art gallery than any other kind of museum.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 Another indication that the paintings were valued as art lies in the fact that after successfully being exhibited in England, Canada and the U.S., they were deposited at the National Gallery of Canada, then located in the Victoria Memorial Building in Ottawa (minus eight large works that were permanently hung in the Senate). The quantity and size of the paintings made them difficult to exhibit, however, and posed storage and conservation problems. Nonetheless, their importance is indicated by the fact that, as R. H. Hubbard, the chief curator of the National Gallery at the time of the transfer observed, "they were often called upon as silent advocates in the Trustees' unrelenting campaign to secure a proper Gallery building."2

7 The Canadian War Memorials was a major inspiration for the founding of the Canadian War Records during the Second World War. Under this scheme, 32 Canadian artists, including successful present-day artists such as Alex Colville, were commissioned to depict the progress and activities of the three services — army, navy and airforce — at home and overseas. The National Gallery, which was involved in managing the program, independently commissioned artists to depict the Women's Services. The cost of running the program was borne by the Department of National Defence. Instructions were issued indicating broadly that artists were to produce an accurate visual record of the war, but otherwise control was minimal (Fig. 2). The documentary role notwithstanding, the collection was still viewed as art and in 1946 the over 4 000 works joined the First World War paintings at the National Gallery.

8 For the next ten years the collection was housed in an ancillary building, and figures like Sir Kenneth Clark wrote of the difficulties they had in seeing the collections.3 A curator of war art was finally appointed in 1960 by the then-director of the National Gallery, Charles Comfort, himself a former official war artist. The third appointee to the position, Major R. F. Wodehouse, made the greatest impact. Appointed in 1962, he tracked down missing works, improved the storage of the paintings, arranged innumerable loans to the military, and set up an index card record of every painting, which remains the most useful reference source on the collection. When the National Gallery moved from the Victoria Memorial Building to the Lome Building on Elgin Street in 1960, the sixth floor was set aside for war art, and it was Major Wodehouse who arranged regular exhibits that celebrated military anniversaries and specific war artists. These shows tended to reflect the documentary nature of the collection, an emphasis that, it should be noted, was to have implications in the collection's future.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 29 The war art collection was referred to as a "unique and important asset" by Jean Sutherland Boggs in 1968. She was then director of the National Gallery of Canada and the words form part of her first sentence in a preface to the Checklist of the War Collections written by Major Wodehouse, and published by the Gallery that year. Only three years after these words were written, however, the bulk of the War Art Collections, over 5 000 pieces, was transferred to the Canadian War Museum and the unique and important asset was gone from the National Gallery. The curator, Major Wodehouse, was also transferred. Without a doubt, this transfer was one of the most massive in the history of public collecting in Canada.

10 While there is no doubt that space constraints in the Lome Building had a great deal to do with the transfer, there are many other factors that have to be considered in explaining such a move. This was, of course, the time of the Vietnam War. While a significant number of U.S. troops had been withdrawn from South-east Asia by this time, the American draft was still in place. The war was extremely unpopular worldwide, and that sentiment found expression in Canada through anti-war demonstrations in front of the Parliament Buildings and the American Embassy. To have had the whole floor of the National Gallery of Canada given over proudly to the display of war art may, at the time, have been politically awkward. Instead, the Gallery sought to emphasize more popularly topical aspects of their collections. The first article in the National Gallery's Review for 1971-72, for example, which also contains the farewell piece on the War Art Collections at the back, is devoted to the subject of "The National Gallery and Women."

11 Probably more important than this, however, was an intellectual concern — the dominance of modernism in art historical circles of the time. The ideals of modernism and its commitment to progress set the standards for the period during which evaluations and decisions were made about the fate of the War Art Collections. The National Gallery was concerned with building its image as an important Norm American museum and, in the period prior to the transfer had begun to acquire a representative collection of American abstract expressionist, pop and minimalist works. The Quebec Automatistes and older examples of Canadian modernism were also being added to the Gallery's collection. In terms of the direction of the Gallery, the official war art, with its basis in the figurative and landscape traditions of the 1930s and 1940s, simply did not fit into the emerging canon. Wodehouse was probably the only curator who knew what was in the 5 000 or so paintings in his care, and one suspects that his concerns reflected his military interests and therefore tended to discount the value of the collection as art.

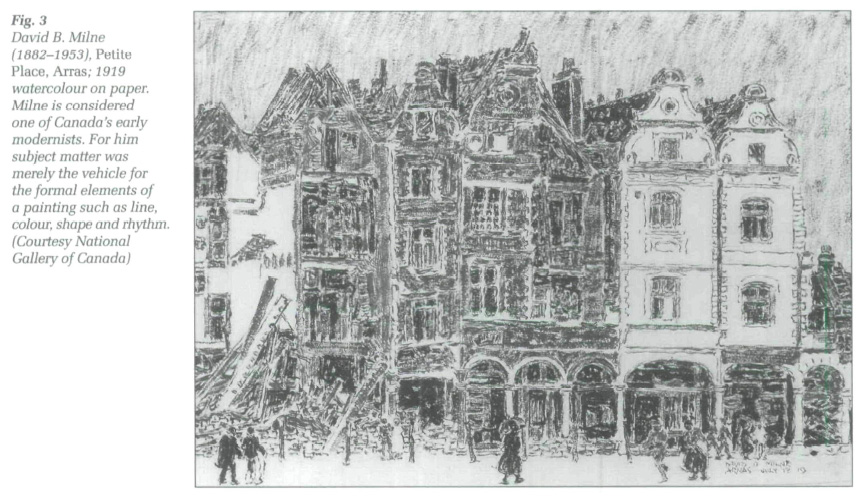

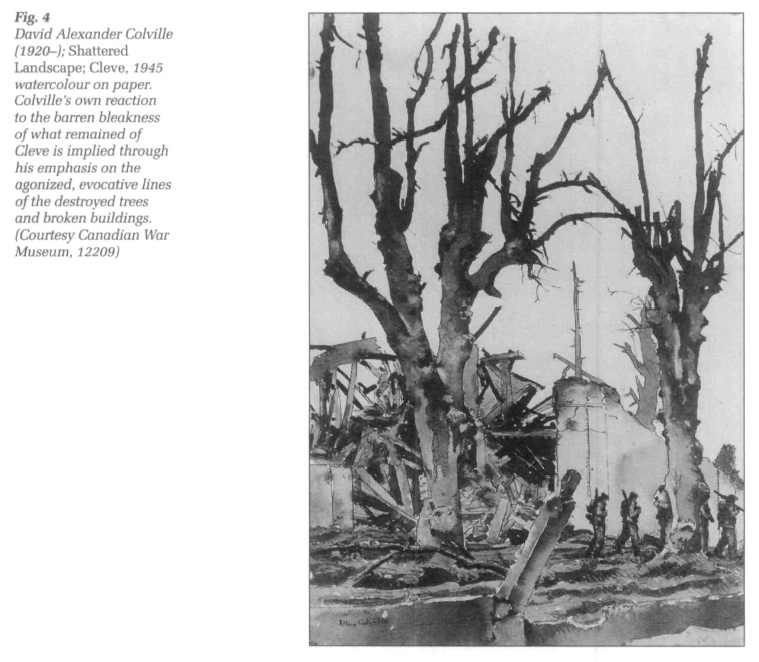

12 The evidence of this leaning towards modernism is nowhere more apparent than in those works that the National Gallery chose not to transfer to the War Museum (thus in effect determining what constituted the "art" in the War Art Collections and devaluing the transferred works). From the Canadian War Memorials Collection, the Gallery retained all die British avant-garde paintings by such artists as Paul Nash, Christopher Nevinson and William Roberts, and all the paintings completed by David Milne — one of Canada's pre-eminent early modernists (Fig. 3). At this point, most of the older Second World War official war artists had yet to be rediscovered and reevaluated (which largely remains the case), and artists such as Alex Colville, now established and successful, were not yet so. In addition, very little of Colville's work could be termed modernist. No official war art from the Second World War program was retained.

13 This leaning towards the modern was, of course, not isolated to Canada in this period. It had its roots in the fact that the Nazi regime in Germany from 1933-45 was virulently hostile to the avant-garde, and instead promoted a more grandiose, neo-classical, figurative tradition in art. Important modernist paintings by artists such as Otto Dix and Emil Nolde had been included in the 1937 "Degenerate Art Exhibition" in Munich. If the Nazi regime was associated with a particular art form it seems almost inevitable that the allied countries would have followed a route that took them as far away as possible from it. Much of post-war modernism emerged from the avant-garde of early 20th-century Europe and came across to North America with the post-war wave of new immigrants and refugees. To support modernism could in some ways be seen as support for the forces of anti-facism.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 314 In a compelling two-part review of three books on Nazi art published in the New York Review of Books in April 1994, writer and critic Willibald Sauerlaender presents a convincing case to account for the disappearance of Nazi art following the war. After referring to what he observed as a prevailing aversion to the art of the discredited Nazi party, Sauerlaender writes:

15 There is no evidence that Canada saw itself fighting fascism in its collecting of modernist art; it was simply keeping up with the trends of the art world. The fact that seems to be forgotten is that the freedom that allowed the modernist ethic to emerge, flourish and become dominant is directly related to fighting and winning two world wars, and the War Art Collections are an artistic expression of this. Beyond this, it is interesting to note that recent research has documented the involvement of the American government in supporting the dominance of abstract art as being representative of American ideas of freedom.5 The corollary was that the support of more traditional and representational art forms could imply a link with reactionary forces associated with figures such as Stalin.

16 Major Wodehouse, the curator of the Canadian War Art Collections at the time of the transfer, seems, perhaps by default, to have accepted the modernist view of the progress of art history. In a memorandum to Boggs, his director, on the subject of the proposed transfer he wrote, "The Canadian War Memorials Collection of World War 1 and the Canadian War Records Collection of World War 2 are primarily collections of historical records painted by the best available artists of each period. As such they do not fit comfortably into an art museum whose prime purpose is to collect and display examples of different schools and styles of painting and sculpture through the ages."6

17 Wodehouse, lacking any training as an art historian, saw little or no historical-art content to the collection but rather, as a military man, saw the collection's chief value as an illustration of Canada's military history. This attitude was confirmed when, in 1969, he described the qualifications for the ideal curator of the War Art Collections as a B.A. in history and an M.A. in military history.7

18 He was not alone in this viewpoint of the value of the collections. As early as the 1951 Massey Report on the Arts, Letters and Sciences, the War Art Collections had been seen as better suited to a museum of history — an institution that dealt with the past — than with one that looked to the future. Recommendation L of the Report states that: "when a suitable building is provided for the Historical Museum it takes over the collection of the present Canadian War Museum; and that the Board of Trustees of the National Gallery transfer to it such of its pictures and portraits as belong more properly to an historical museum than to an art gallery."8

19 What is so remarkable about this report is that only a year before, Graham Mclnnes had published a second edition of his book, Canadian Art,9 whose tenth chapter was entirely devoted to the artists of the Second World War. This author did not see their work as documentary, but rather as:

20 The literature charts a slow downgrading of the significance of war art in the second half of the 20th century subsequent to the Massey Report. R. H. Hubbard's The Development of Canadian Art11 published in the early 1960s, integrates the war art into the biographies of the individual artists. Perhaps this too was in keeping with a period that championed the individual. At the time of the transfer, the war art of Canadian artists remained a brief point of activity in the surveys of individual artists in the histories of Canadian Art by both Russell Harper and Denis Reid.12 Only Barry Lord, in The History of Painting in Canada13 with his particular Marxist bias, devotes any space to the Second World War art program as an entity in its own right. He comments on a photograph of artist F. B Taylor's 1944 exhibition of "heroic portraits of workers" held in the meeting rooms of Lodge 712 of the International Association of Machinists that, "Advancing together in the common struggle of the war, artist and worker here take a long step forward toward a people's art."14

21 It is worth noting, as well, that at the time of the transfer, a book on Alex Colville about to be published demonstrated the importance of his war art to his future development.15 However, given that Colville's art was so highly figurative (Fig. 4), it seems unlikely that this carried much weight in a period caught up in the wonders of abstraction.

22 The Canadian War Museum certainly wanted the paintings in die War Art Collections. Members of staff from that era have suggested that the director of the Museum at that time, Lee Murray, spoke to Jean Boggs about assuming responsibility for the collection and that things moved on from there. Given the huge space problems the Gallery was dealing with it must have seemed a rational route to follow. As Denis Reid put it, "the Gallery cherished parts [of the war art collections], but the whole was a burden."16 The transfer ensured that the Collections would remain in the nation's capital but that the responsibility for care would be transferred to another institution. Certainly Wodehouse's detailed memo on the subject to Boggs was supportive of the transfer. He may well have been feeling anti-Gallery at the time, for in 1969 he had grieved his new classification as being too low for the responsibilities he carried.17 Certainly the position of curator of the War Art Collections was assigned a significantly lower grade than the other curatorial positions. As well, Wodehouse had been losing space on an ongoing basis and the technical support he had enjoyed in the early days was fast being directed elsewhere. In the end, he moved, seemingly thankfully, with the Collections to the War Museum.

23 Unfortunately for the cohesion of the War Art Collections, a debate about what should or should not be transferred appears to have ensued. No one seems to have objected to the idea that paintings like Benjamin West's Death of Wolfe might remain in the Gallery, since they had not been part of any official war art program. However, the important British avant-garde pieces were retained as well as, at the last moment, the paintings of David Milne. As would eventually have happened to the War Art Collections as a whole had they remained at the Gallery, these pieces have been integrated into the different collections of that institution, which are divided by geography and medium. Within the War Museum the art remains a coherent whole, undivided by country, school or medium. And the collection has retained its official name: The Canadian War Art Collections.

24 For the next two decades, the War Art Collections were used to document Canada's military history in exhibitions, commemorative events and books. Two publications at the end of the first decade momentarily suggested that there might be another way of looking at the collections other than as records of war. These are Heather Robertson's lavishly illustrated 1978 compendium of prose and poetry, A Terrible Beauty18 and Joan Murray's 1981 art historical survey, Canadian Artists of the Second World War. Maria Tippett's 1984 book, Art at the Service of War19 admirably documented the First World War program.

25 Recently, however, the collection has gained a new relevance to art history when considered in the light of post-modernist thinking. This has discredited the purely aesthetic or documentary value of art and has called into question the absolute or authoritarian notions concerning what is and what is not good art. This has resulted in the social context within which the art was created, assuming a renewed importance in determining how art is viewed and assessed. To some degree, post-modern approaches have permitted the historical context at the time of creation and the time of assessment to be key factors in assessing art's importance, rather than aesthetic values of an absolute nature. Examined in this light Canada's War Art Collections can be reevaluated as works of current relevance.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 426 Possibly this accounts for the increasing number of requests for the war art on the part of art galleries across the country and its heightened visibility in art journals. Certainly it accounts for the growing number of students examining issues relating to gender as exemplified in Canada's war art. It may also account for the change in attitude on the part of the Collections' original custodian, the National Gallery. In a letter of December 1992 requesting a loan from the War Art Collections, the director of the National Gallery of Canada, Dr. Shirley Thomson wrote:

27 The Canadian War Art Collections have undoubtedly benefitted from a dramatic shift in emphasis in the study of art history. Twenty years ago the formal concerns that characterized modernism predominated. Since then revisionist theories regarding the nature of art history have made it possible to examine Canada's creative past from viewpoints that were almost unimaginable in the immediately post-war period. In consequence, war art can now be viewed from perspectives that were not stifled by the heavy hand of the modernist aesthetic. In the absence of a defensible canon as to what constitutes Canada's artistic past, the War Art Collections have been reinstated as "a unique and important asset" in this country.