Articles

Striving for the Divine Ornament:

Change and Adaptation of Hutterite Women's Dress in North America

Abstract

The author quickly traces the history of the Hutterites' forced wandering through Eastern Europe and their emigration to North America and settlement on the U.S. and Canadian prairies, and compares contemporary Hutterite dress with the garments found in the collection of the three large museums in western Canada. She discusses the role of dress in Hutterite religious and daily life, and also traditional and contemporary garment construction, including the short-lived practice of fabric painting. Although Hutterite dress seems frozen in time, comparison of contemporary dress with garments in museum collections reveals that it is susceptible to some change — towards simplification.

Résumé

L'auteure décrit rapidement l'histoire des déplacements forcés des Huttérites en Europe de l'Est, leur émigration en Amérique du Nord et leur établissement dans les plaines américaines et canadiennes. Elle compare les vêtements contemporains des Huttérites à des vêtements trouvés dans les collections de trois grands musées de l'Ouest canadien. Elle traite du rôle des vêtements dans la vie religieuse et quotidienne des Huttérites, de même que de la fabrication des vêtements traditionnels et des vêtements contemporains, notamment la pratique, de courte durée, de peindre les tissus. Bien que les vêtements huttérites semblent être figés dans le temps, la comparaison des vêtements contemporains à ceux des collections de musées révèle qu'ils ont subi certaines modifications — vers la simplification.

1 Everyone has a friend who regularly complains that she has nothing to wear while her closet bulges with clothes. Her complaint is not that she cannot cover herself, but that nothing in her closet exactly expresses what she wants to communicate at that time. Our clothing does more than provide cover: it carries messages to everyone we meet. It is a code transmitting signals about our wealth, our background, our interests, our work and many other things. These messages overlap and are blended into a unique mix presenting our image.

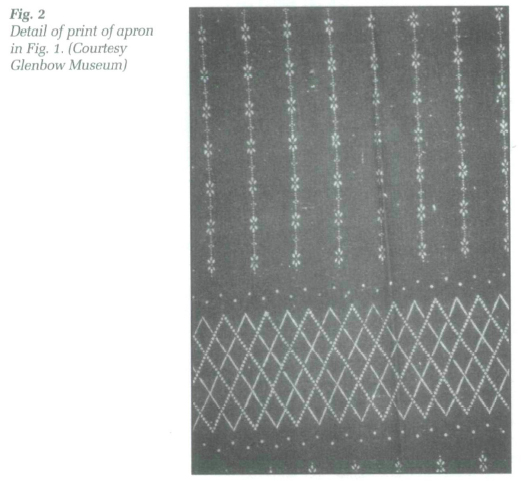

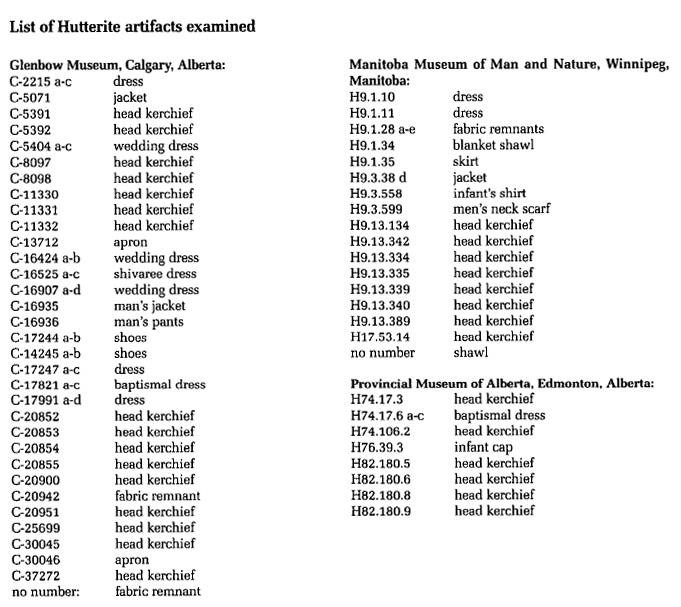

2 This article is about the clothing of the Huttérites, a religious group whose dress is designed to express complete detachment from worldly concerns such as material wealth, rank or status. This investigation was inspired by an interesting blue and white resist-printed cotton apron in the collection of the Glenbow Museum. The fabric of the apron is reversible: each side features a simple but different print (Figs. 1 and 2). The understated elegance of this apron is so unlike what the Hutterite women are wearing now, that it begged investigation. The author has examined clothing in the three largest Hutterite collections in western Canada: the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, the Provincial Museum of Alberta in Edmonton, and the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature in Winnipeg (see list of artifacts in Appendix A). Between 1992 and 1995 she visited eight colonies representing all three Hutterite branches: five Dariusleut colonies and two Lehrerleut colonies in Alberta and one Schmiedeleut colony in Manitoba. These visits lasted often more than three hours, during which families, mostly women, but also men, were interviewed. A couple of Hutterite women who were interested in their heritage were invited to visit the Glenbow Museum and view the Hutterite collection. Museum staff made notes of their remarks while viewing the artifacts. In addition two contemporary fabric suppliers to Hutterite colonies were interviewed.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 Comparison of the clothing worn now with that in museum collections reveals that Hutterite dress, so timeless in appearance, has undergone several changes in the last 125 years. These changes are not dramatic, especially when compared with women's fashions in society at large during the last century. However, Hutterite women's dress became simpler in cut and construction and the range of the surface embellishments of its fabrics narrowed. This article explores some of the contributing factors.

4 Hutterites are a familiar sight at farmers' markets in any city on the Canadian prairie: bearded men in black and women in ankle-length dark coloured dresses, their heads demurely covered with polka-dotted scarves. Visitors from Ontario might be reminded of the Amish. Like the Amish, Hutterites are Anabaptists. Anabaptists are protestants who believe that baptism is a confession of faith and an act of commitment to God. Since only adults can confess their faith and make an informed commitment, Anabaptists do not agree with infant baptism, but instead insist that only adults can take this step in order to become members of a Christian congregation.

5 Unlike the Amish, Hutterites believe that the best way to personal salvation is through communal living. The Hutterites follow the footsteps of the earliest Christians by the literal interpretation of Acts 2:44: "and all that believed were together and had all things common." Other Anabaptists take this to mean that members of the congregation should help each other out when the need arises. Hutterites, however, interpret this verse literally and have developed a system of communal living, in which both the production and the use of goods are shared.

6 Their communal ownership and sharing of goods started in Europe during the Protestant Reformation in the early sixteenth century. In 1528 Jacob Wiedemann, an Anabaptist leader and a founding father of the Hutterite faith, spread out his coat on the ground and encouraged his followers to deposit all their assets on it. These were then divided equally. Thus started the first Bruderhof, a "garden of brothers" or colony, of the Hutterites.

7 From the early sixteenth century until the late eighteenth century their communal lifestyle, their pacifism, and their beliefs (especially their renunciation of infant baptism and their insistence on being baptized as adults) roused the wrath of officials of established churches and the suspicion of temporal rulers.2 Forced to flee persecution during almost every decade, they wandered through what is now Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary to Russia, where they found peace for a few generations from the late eighteenth century until the nineteenth. Ironically it was here, where they were undisturbed, that the Hutterites abandoned their communal lifestyle and lived among the German-speaking Mennonites in Molotschna, in the southern Ukraine.

8 In the late 1860s, however, they experienced a rebirth of their faith and started to return to communal living under the guidance of two spiritual leaders. One was Michael Waldner, a blacksmith, and his followers are called the Schmiedeleut, or "smith people." The other was Darius Walter, whose followers are called the Dariusleut, or "Darius' people."3

9 In 1874 Csar Alexander II introduced military service for all his subjects, and pacifist groups such as the Hutterites were not exempted. About one hundred Hutterite families (roughly eight hundred people) decided to move again, this time to North America. Both leaders founded a new colony in what is now the state of South Dakota. Jacob Wipf, a teacher, founded a third colony. They are called Lehrerleut, or "teacher people." Only about half of the immigrant Hutterites lived in one of these three colonies; the rest took up individual farms and are known as Prairieleut, or "prairie people."

10 For several decades, until the outbreak of World War I, the Hutterites lived and prospered again. Although the United States remained neutral until the last year of the war, zealous patriotic officials harassed the pacifist German-speaking Hutterites. In 1918 several young Hutterite men were forced to go to a boot camp in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where they refused to take off their Hutterite clothes to put on military fatigues. They were thrown in jail and mistreated. When two of the young men died in jail, many Hutterites decided to move to western Canada.4 They established ten colonies in southern Alberta, and six in Manitoba.5 Today Hutterites have colonies in all three prairie provinces of Canada: the Schmiedeleut live in Manitoba, while the Dariusleut and the Lehrerleut live in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

11 The three branches of the Hutterites, the Dariusleut, Schmiedeleut, and Lehrerleut, differ in principle very little from each other. They have the same religious observations, yet some aspects in the regulation of their daily lives have the effect that they seldom or never inter-marry. Most obvious are the subtle differences in dress: the Leherleut being more conservative, prefer darker colours, while the Schmiedeleut allow their women to wear a wider range beyond blues, dark greens and blacks, to medium browns and maroons. While Hutterites themselves quote the different dress codes as the main obstacle for intermarriage, Bennett (1967) speculates that the difference in the style of managing the production and the finances of the colonies are also an important factor. When he studied the Hutterites in Alberta during the 1960s, he found that the Lehrerleut tended to maintain mixed farming operations, with a fairly conservative risk management. Dariusleut on the other hand tended to invest into whatever paid well at the moment, and would drift into some specialties. Dariusleut were also willing to form daughter colonies about five years earlier than Leherleut, even though this could mean that both mother and daughter colonies might face shortages in labour and resources for several years. The development of differences in economical expectations and experiences could contribute as much as, if not more than, any differences in clothing to the current endogamy of the three branches.6

12 The life of a Hutterite is the preparation for the life hereafter and is totally permeated with God's word. The appearance and the construction of their clothing are the direct results of a logical application of fundamental Christian teachings. Clothing must cover the body and indicate the gender of the wearer. It should not distract wearers from their faith by pleasing the senses of the body. Also, without being expressed in so many words, clothing has to protect the body: from heat, cold, insects, wind, sun, grease and dirt.

13 Part and parcel of living in a community of equally shared goods is a prescribed dress. In the sixteenth century Hutterites formulated general dress regulations so that no one would wear clothing made of costlier material than that of their neighbours or use more yardage. Fabrics are still bought in bulk and divided among the families according to their needs, as laid down in time-proven rules. The clothing is simply and economically cut, keeping modesty in mind and allowing for ease during manual labour. All outward decoration is avoided. There is no place in a Hutterite colony for signs of rank or status or for show of material wealth; nor is any innovation in the cut or construction of clothing encouraged. To the eyes of the world the combination of shared fabrics and prescribed patterns results in something of a uniform, a fact appreciated by the Hutterites themselves. It does more than distinguish them from the Weltleut, the "worldly people." As the Hutterite author, Paul Gross, has observed:

14 As noted earlier, Hutterites are easily spotted in an urban crowd. Men wear a straight, collarless jacket and a pair of pants of strong black material. Suspenders hold up the pants: a Hutterite does not wear a belt. The jackets of the Dariusleut and Schmiedeleut are usually closed with hooks and eyes, while the Lehrerleut use buttons. During weekdays a man wears a dark coloured shirt; for church and on Sundays he wears a white one. Traditionally, Hutterite men wear plain black broad-rimmed felt hats, which today in Alberta is often a black cowboy hat (Fig. 3).

15 Hutterite women wear a dark coloured two-piece dress with a matching apron. The dress consists of a jacket and skirt and is usually black or dark blue, but may be dark brown or green. Underneath the collarless jacket is a light coloured printed blouse, barely visible under the high neckline of the jacket. Also unnoticed by towns people is the light coloured fabric cap that Hutterite women wear over their prescribed hairdo. Like several other Anabaptist groups, such as the Amish and some Mennonites, Hutterites take to heart St Paul's admonition in his First Letter to the Corinthians (chapter 11:3-16). Therefore, baptized women must have their heads covered twenty-four hours a day. Outside their own homes Hutterite women always cover the cap with their hallmark: the polka-dotted kerchief.

16 Most Hutterite clothing is made at home, and close examination of the garments reveals that the construction is not always simple. The dress jackets close in the centre front with eight to ten snap buttons and the sleeves may be long or reach to the elbow. They may have one or two waistline darts, and the side seams often incorporate an extra fold of material. The skirts are gathered tightly in the back while they are smooth in the front. They close in the centre front with a simple plain button at the waist-band. A fairly deep pocket is set in on the right-hand side of the centre front opening to keep small personal items such as a house key. A large apron is always worn over the skirt, which often matches the dress. The blouse underneath the jacket is made of a light coloured fabric, usually a small floral print. It may have long or elbow-length sleeves, but is never sleeveless. The blouse closes in the centre front with small plain buttons. In town one can only see the collar of the blouse, which is just a high stand-up band if the woman belongs to the Lehrerleut, but is turned down if she belongs to the Dariusleut.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 317 A visitor arriving in a colony early on a weekday will see several wash lines hanging full of family clothes: There are the sleepers of baby boys, small long dresses and tiny fabric caps of baby girls, bright blue little overalls with tiny white shirts for the boys, and the brightly coloured dresses of their sisters. Unlike the grown-ups, small children, especially toddlers, wear brightly coloured clothing. Underwear for the whole family in printed machine-knit cotton flutters in a drying breeze: bloomers, long in the winter, short in the summer, underpants, undershirts, cotton slips and half slips. Rows of socks for the whole family, once all hand knit, are now mostly commercially made. Some are still hand knit of wool for the men who prefer the absorbency of wool for their work socks.

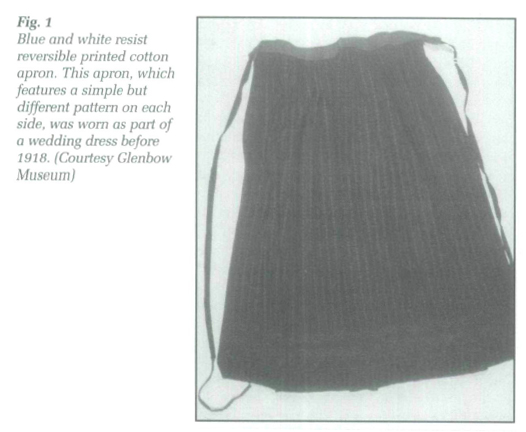

18 Although the clothes seen at the farmers' market give the impression of timelessness, their comparison with older garments in museum collections reveals that Hutterite clothing is susceptible to change. Style changes do occur, but at a very slow rate and far less strikingly than the styles of the Weltleut, society at large. One of the oldest Hutterite dresses in a museum collection in western Canada is in the Provincial Museum of Alberta (H74.17.6 a-c), ca late 1870s. The dress fabric is a fine black plain weave wool with a more prominent yarn every fifth or sixth warp as the sole decorative touch. The shoulder and side seams of the semi-fitted jacket are placed far back, reminiscent of their placement in the high fashion jackets of the 1870s. The shoulder and the armhole seams are finished with a black braid, echoing the construction of high fashion dress in the third quarter of the nineteenth century. The hem in the centre back of the jacket has a small trapezoid gore, about seven centimetres high. The gore is like a vestige of the pleats in early 1870s jackets flaring over a bustle with many pleats. The jacket closes at the centre with ten hooks and eyes. It is lined with indigo blue cotton fabric with narrow white stripes. The edge at the waist is faced with a black cotton print with small buds and dots in white. The ends of the sleeves are lined with strips of blue fabric with woven-in stylized flowers in black.

19 The back of the skirt is made of two widths of fabric, with a long triangular gore at the centre. One edge of the fabric has been folded over and basted with three rows of running stitches in a double strand of strong thread, and then carefully pulled to form tight even cartridge pleats, or fallene as Hutterite dress makers call them. The fallene are sewn onto the waistband, and finished on the inside with a strip of black polka-dotted cotton. Some cross stitching — the letter S and number 4, reminders of the initials of the previous owner and a date — is still visible among the polka-dots, a silent testimony to the thrift of the seamstress recycling an old head kerchief to finish the new dress. The skirt front is closed at the waistband with a small white opaque glass "pie-crust" type button, popular in North America during the late nineteenth century, but not manufactured after 1920. A two-centimetre deep tuck is basted parallel to the hem. The edge of the hem itself is reinforced with a purple crocheted braid.

20 The dress apron is made of two pieces of fine black wool, but not of the same fabric as the dress. The dress belonged to the mother of the donor who was born in 1890 in the Dariusleut colony in Olivet, South Dakota. It was very likely made during the last decades of the nineteenth century. The dress is catalogued as a funeral dress, but it is possible that it was also a baptismal dress. Baptism is the single most important event in the life of a Hutterite: it is an act of commitment to God, a confession of faith, a rite of passage in becoming a full member of the congregation. As mentioned previously, Hutterites are convinced that such a commitment can only be made by a mature person, never by a child. At age fifteen, Hutterite children are considered adults, able to take their places as productive members of the colony. However, baptism is not automatically administered to any fifteen year old. The young person must make a request to be baptized, which is granted only after several months of thorough religious training. Young people are encouraged to take their time considering this momentous event. Baptism is an irrevocable step, more important than the decision to marry. Since only baptized Hutterites are allowed to marry, most, but not all, young Hutterites wait until they are in their early twenties and feel ready for marriage to express their wish to be baptized. The only event in a Hutterite's life more important than baptism is death. This is the Hutterite's ultimate destination; earthly existence is viewed as a time to prepare oneself for the life hereafter and to be at one with God.

21 In contrast with other Christians, Hutterites do not wear white during baptism. My Hutterite contacts could not tell me why, in this respect, they do not follow the early Christians, who gave their baptismal candidates white clothing, symbolic of their souls newly cleansed from sin. For Hutterites, black is the preferred colour for church wear and for such an important event as baptism it is the prescribed colour.

22 If black is reserved for church wear, some colour is allowed for other occasions. The Glenbow Museum has two dresses made from a multi-coloured plaid. They were both worn as wedding dresses in South Dakota before 1918. One dress (C-17247 a-c) is made of a plain-weave fabric with a balanced plaid in red, dark green, navy blue and black. The dress is complemented with a triangular neck cloth of the same plaid fabric as the dress, finished with a rolled hem on the two straight sides, while the side cut on the cross of the fabric is left unfinished.

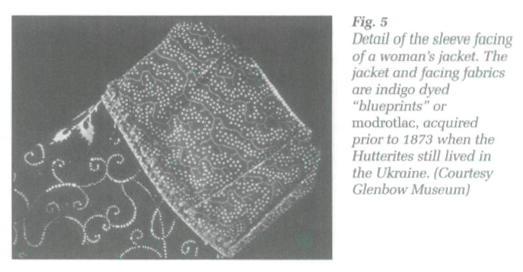

23 The jacket is semi-fitted and does not have any darts. In cutting out the front pieces of the jacket the dressmaker did not take care to let a dominant stripe of the plaid continue from one side to the other, nor to let the hem at the waist follow one of the dominant stripes. The neckline is slightly scooped, and bound with a strip of black polka-dotted fabric. The centre front closure has nine hooks and eyes, the eyes being sewn on a separate strip of another plaid fabric as an underlap. The bodice of the jacket is lined with a woolen twill plaid fabric, the same as used for the underlap of the closure. The long sleeves are cut straight, but are pieced together from bits of fabric. As in many Hutterite jackets, the main seam of the sleeve does not meet the side seam of the bodice at the armhole, but is placed slightly to the back in the armhole. The raw edges of the fabric inside the armhole are overcast with a coarse thread, probably linen. The sleeves are lined with a cotton flannelette printed with a plaid in green, black, white and yellow, while the cuffs are faced with a plain weave cotton print featuring sprigs of flowers and oval cartouches with buds in purple, turquoise and green.

24 The skirt is similar to the previously discussed black dress of the Provincial Museum of Alberta, except that it does not have the triangular gore set in at the centre back and it has a set-in pocket about eleven centimetres on the right-hand side of the vent. The pocket placket is made of purple plain-weave cotton with a woven-in stripe and a twill spot, and the pocket fabric is a pink and white gingham. The raw edges of the seam allowances of the pocket and the placket are finished with overcast stitches in black and purple threads. The hem is faced with a six-centimetre wide strip of plain-weave cotton printed with pink and green stripes and sprigs of stylized flowers on a maroon background. The edge of the hem is finished with a maroon braided cord.

25 The second plaid dress (C-16907) is black, blue, green, red and yellow. It has a bright green crepe neck cloth and an indigo dyed cotton apron featuring small geometric motifs printed in stripes and a simple border close to the hem. At each side of the centre closure the jacket has two darts that form pleats at the waist. The front closure has eight hooks and eyes, the eyes being sewn on a separate strip of black fabric as an underlap. The dressmaker of this dress was a bit more careful in cutting out the jacket pieces: the horizontal lines of the plaid match in front and back. The vertical lines of the plaid almost match. They would if the seamstress had moved the pattern piece about four centimetres over on the fabric. The hem of the jacket does not follow a horizontal line of the plaid. The neckline is finished with a strip of black woolen twill. Stitch marks in the upper arm area suggest that there was once a two centimetre deep tuck basted in the material, which later was taken out. The skirt of the dress is similar to the other one, but without a pocket. A facing 4.5 centimetres wide finishes the inside of the hem with a colourful floral print with baroque scrolls in yellow, red, dark blue, and green (Fig. 4).

26 The various fabrics for the facings and linings are mentioned because their use is characteristic of Hutterite dressmaking. While in our society dressmakers use the same fabric for their facings and reinforcements, take care to use fabrics of a matching colour for the lining, and buy some extra yardage to make sure that they have enough fabric, Hutterite dressmakers have to juggle with a standard amount of fabric, carefully calculated to leave nothing extra for frills and decoration. Hutterite dressmakers traditionally save all pieces left over from sewing projects and the stronger parts of discarded garments for mending and unnoticed details such as set-in pockets.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 427 While the outside of the garments is devoid of any decoration, the colourful facings and linings are carefully chosen to give a pleasing contrast to the main fabric. Except the sleeve facings, which are visible only when the women roll up their sleeves a little, no one will see these touches of colour and no one can comment on them. Created by thrift, these inner patches of colour seem to celebrate the virtue of the soul within.8 Men and women have their clothes ornamented in this way. A particularly good example is a man's jacket of a sturdy black cotton twill in the Glenbow collection. It is lined with a rich Paisley print in blue, green, and yellow with a bright red background (C-16935). This jacket was worn in 1938 by a Dariusleut bridegroom in the Rosetown Colony of Saskatchewan.

28 The dress of his bride is also in the Glenbow collection (C-16524 a-b). It is made of a navy blue damasked rayon with a geometrical pattern reminiscent of a colonial overshot coverlet. It is machine-sewn with an uneven tension. The high neckline is finished with a navy blue cotton tape. The shoulder seams are placed on the natural shoulder line. The centre front closure has eight hooks and eyes, and has an underlap made of lining fabric. This lining fabric is a plain-weave cotton with a blue and black plaid printed on it. There is one waistline dart on each side of the jacket front, but stitch marks suggest that there were once two darts. Usually the side seams do not meet the sleeve seams at the armhole but rather incorporate up to four centimetres of extra fabric to allow for potential alterations. The armhole seam is finished with overcast stitches in pink crochet cotton.

29 The skirt features fallene in the back, reinforced with a double strand of black thread basted through the pleats about five centimetres below the waistband. The upper part of the centre front of the skirt, in which the vent and the pocket opening are located, is made of white and blue plain-weave check. The set-in pocket is made of a fabric with a composite woven check in blue, brown, black and white. There is a two-centimetre deep tuck basted in the skirt with black thread about twenty-six centimetres above the hem. The six-centimetre wide hem facing is made from a cheerful madras plaid in white, red, black, yellow and grey. The apron worn with this dress is not in the collection.

30 A similar two-piece dress of navy blue rayon with only a small square dobby pattern was worn by the same bride during the shivaree (C-16525 a-b). This is the communal songfest on the evening before a wedding ceremony. It is one of the few occasions when Hutterites may sing non-religious songs. The whole colony and all the relatives of the young couple are packed in the communal dining room and enjoy the singing of their favourite hymns and traditional German songs. Often this song fest is repeated the next day in the afternoon after the wedding ceremony.

31 While baptismal, wedding and church dresses are made of dark coloured solid fabrics, working dresses feature prints. One early Hutterite work dress is on display in the Grasslands Gallery of the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature (H9.1.10 and H9.1.11). The over-all pattern features sprigs of feathery flowers with tiny leaves in greenish yellow. A jacket with a bolder print of yellow swirling spirals with yellow and green leaves is in the Glenbow Museum (C-5071; Fig. 5). The long sleeves are worn. The left elbow has a hole, revealing the lining, which is made of another "blueprint." The pattern of the lining is very simple: vermicular lines of small dots snaking through a field of larger dots. The sleeve ends are faced with a blue and white cotton pin-stripe. The hem at the waist is finished with a strip of me fashion fabric.

32 The fabric of these two garments is indigo dyed with resist printing. It is similar to the fabric worn in the folk dress of the Lausitz area of eastern Germany and Slovak blueprints (blaudrucken, or modrotlac) described by Sigrid Piroch.9 Sarah Tschetter remembers her grandmother telling her that in Russia, Hutterite women used to make their own cloth, which could be dyed by an itinerant dyer, whose work was similar to that of the Slovak dyers as described by Piroch.10 The Hutterites call this type of fabric "Russian Cloth." These lovely indigo dyed prints were acquired when the Hutterites still lived in the Southern Ukraine.11 We can get some idea of the variety of patterns from the facings and linings of many dresses made in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A few strips of these prints, saved for a special project, landed in the collection of the Glenbow Museum and the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature. One strip in Winnipeg (H9.3.38 d) features the same pattern as the Glenbow jacket C-5071.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 533 The Glenbow also has some blueprinted cotton aprons in its collections. One of these was worn with the plaid wedding dress described earlier (C-16907-d, Figs. 1 and 2). It is printed on both sides with a striped pattern and a border along the hem, but the stripe and border are different on each side. One side features stripes formed by pairs of small elongated crescent shapes alternating with groups of five dots like a stylized flower. The decorative border near the hem features scrolling motifs with stylized tre-foils. The other side has stripes formed by lines of small dots interspersed with stylized sixpetalled flowers and the border is a trellis of interlacing zigzags. The bride chose the side with the scrolling border as the "right" side, but the apron fabric is carefully sewn to the waist-band so that it could be worn on both sides. The fabric was originally about 120 centimetres wide. A piece of about eighty-six centimetres is gathered onto a waistband of blue cotton twill. Black grosgrain ribbons serve as ties. Aprons like these were heirlooms, and were prized not only among the Hutterites, but also by the dyers who produced these masterpieces. In Slovakia a few dyers still produce apron fabric with different patterns on each side, but the work is not always done with the finesse evident in this apron.

34 Two other aprons in the Glenbow collection are printed on one side only. One (C-13712) is a navy blue apron with light blue stripes in the centre, a floral border on three sides of the apron, and a second, larger, floral border along the hem. The floral pattern is in white and orange. The waistband is made of a strip of a much simpler floral resist print in white and dark blue. The other apron (C-2215 c) has a black background and is printed with rows of scrolls, dots and stylized leaves and a simple border of small half sunbursts. This apron is monogrammed in small cross stitches [D W for Dora Wipf) and dated 1920. The cross stitching, traditionally done over two warps and two wefts, is fine, due to the high yarn count of the apron fabric.

35 Blue printed cotton cloth was fashionable in Europe in the late eighteenth century. Dyers and print works were established in France and Germany. The printed cloth and later the aprons became popular in rural areas of central and eastern Europe. Several German fabric printers continued to provide blueprints for the rural markets until the early twentieth century. In remote areas of central and eastern Europe, local fabric printers developed their own procedures, producing patterns that were not as fine as the sophisticated design of the German factories, but had a sturdy charm of their own. Aprons similar in design as to those used by the Hutterites, but much wider, are worn in the Lausitz area in Germany and are still made in Slovakia.12 It is very likely that the sturdy floral motifs on C-13712 were printed by a local dyer, using woodblocks, while the fine lines and dots of aprons C-2215 c and C-16907 d suggest the work of a factory using blocks with thin metallic strips and pins.

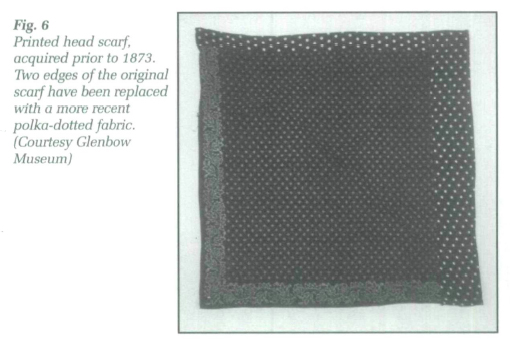

36 Strips of Russian cloth were also recycled to trim the polka-dotted head kerchiefs. Old kerchiefs, like C-20854 in the Glenbow Museum, feature a sturdy border print of scrolling branches with roses and the centre filled with groups of five pin dots, resembling small flowers (Fig. 6). In Russia, where farm women preferred to wear bright red kerchiefs, these dark blue ones were the simplest and the most modest of their kind. In North America, however, where at times it was hard to get even polka-dotted fabric, these kerchiefs were special, to be worn for church and weddings only.

Display large image of Figure 6

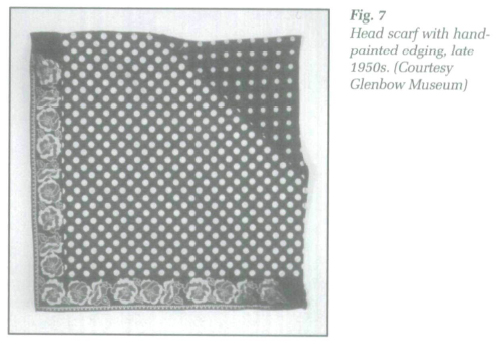

Display large image of Figure 637 Whenever black fabric with white dots of the right size was unavailable, women made their own. They made a grid of dots on a sturdy piece of paper and perforated them. The placement of the dots was transferred onto the black fabric with a powder. Some women preferred a chalk-saturated blackboard eraser for this task. With the help of a nail, the head of the right size, approved by the colony minister, the women printed their own dots: they dipped the nail head into some left-over house paint and stamped it on the spot indicated by the chalk.13

38 When strips of the original Russian borders became scarce — and with the large size of Hutterite families, it is surprising that it took more than fifty years for the original supply to run out — teenage girls began to paint the borders as well as the shawls. They copied a pattern from the head kerchief of their mother or their grandmother onto a strip of sturdy paper, perforated the lines of the design, and transferred it to strips of sturdy black satin. There was always a little leftover white and light blue house paint for such a project (Fig. 7).

39 In the early 1960s at one of the annual conferences of Hutterite ministers, it was recognized that these borders had little to do with the adornment of the soul, contradicted the renunciation of worldly ways, and were not conducive to an attitude of modesty and humility. Around 1963 at the annual conference of the ministers of each branch, they banned the wearing of these painted kerchief borders and the use of all so called Russian cloth.14 Many Hutterites put their old patterned cloths in the bottom of their personal trunks, some sold them to dealers or to museum collections, and others decided to burn the offending, but tempting, fabrics.

40 This is not the first, and probably not the last time, that the conference of Hutterite ministers has banned details or parts of their dress. Late nineteenth-century Hutterite dresses feature narrow braids at the hem, an area susceptible to much wear. The braid functions as a reinforcement of the very edge of the hem. Often these braids were made in a colour contrasting to the background material: wine red or variegated green and yellow on dark blue. Shortly after the arrival of the Hutterites in Canada these braids were seen as ornamental and were forbidden. Sometime earlier the reinforcement of armhole seams was forbidden as too decorative.15

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 741 While some vestiges of nineteenth century dress construction were banned, other details were simply abandoned.16 Once Hutterite women used to wear neck cloths in the fall and winter and large shoulder shawls in the winter. Both were made of wool. The fringed winter shawls, which were heavy duty outdoor garments, were usually made of a heavy blanket-type fabric with a reversible pattern in two shades of grey. The neck cloth on the other hand was made of light woollen dress fabric. The lower corners of the shoulder shawls were embroidered with a corner ornament flanked by the initials of the owner and the date. The neck cloths were abandoned sometime in the 1940s, when women began to sew collars onto their blouses. The heavy shoulder shawls were no longer made by the 1920s. These large winter shawls were not replaced with a coat and today Hutterite women line the jackets of their winter dresses with a quilted fabric produced for the insulation of ski jackets.

42 Other updating of the Hutterite dress is due to modern technology. Many older Hutterite dresses have a two-centimetre deep tuck basted in the skirt, parallel to the hem, and a similar tuck in each jacket sleeve. It is said that these tucks were a kind of "shrink-insurance." If the fabric shrinks a little during laundering, the owner of the dress can salvage it by taking out these tucks.17 The "shrink-pleats" are not a typically Hutterite characteristic; they are also observed on the skirts made in Russia by Doukhobors and Mennonites, and can be seen in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographs of folk dress in central and eastern Europe. Since the adoption of modern shrink proof fabrics, these shrink pleats are no longer necessary.

43 Hutterites have adopted polyester since it was marketed twenty years ago. While natural fibre snobs among the Weltleut, i.e., society at large, might look down their noses at polyester, Hutterites appreciate its strength and its time-saving easy-care qualities. Senior members of the colonies remember how wool used to shrink and how much time and effort were spent on ironing clothes. The most popular dress fabric today is a type of non-pilling, knit polyester manufactured in Georgia, in the United States, and marketed under the name Softique. Practically all work dresses and many wedding dresses are made of Softique in a great variety of prints, designed specifically for the Hutterite market.18 Polyester is used for men's garments as well, especially for town and church wear.

44 Solid dark blue and black are still the preferred fabrics for church wear. Deep dark blue is the most popular colour for weddings, but today brides may wear a deep purple. Women of several Dariusleut colonies visited during July 1994 mentioned that they like the Japanese damasked polyester available at an East Indian fabric shop in Calgary. In the past women were isolated from shops and trade and the discovery of this shop illustrates how things have changed today. Before the adoption of the van and truck by Hutterite colonies, a trip to a large city with a horse and wagon could take more than a day and involve a stay in a hotel or with a farmer. Under these circumstances women seldom went to the city. Today they accompany their husbands or brothers to the farmers' markets and put their time in the city to good use by making price comparisons of yard goods, notions, and sewing machines. The little East Indian fabric shop is situated far off the beaten track on a strip mall in a residential area in Calgary, yet it was discovered by Hutterite women within six months of opening.

45 Like most modern fabrics, Softique and the Japanese polyester are available in much larger widths than was standard thirty years ago. The traditional yardage meted out to each family therefore goes a little farther: the aprons of the Dariusleut, for instance, are now of the same fabric as that of the dress itself. Similarly the wider fabrics make it possible to make at least one coordinating cap with each blouse.

46 Modern sewing machines made the construction of the fallene superfluous. A ruffle attachment with most sewing machines makes quick work of this detail. The gathers are a bit smaller and flatter, but for the uninitiated it does not make any difference. If the colony can afford it, brides are presented with top brand sewing machines equipped with cams or other appliances for decorative stitching. Imaginative use of these machines is seen in the finishing of children's clothes: baby girls have their dresses edged with simple but very decorative variations of the zigzag stitch in the main colour of the print. Young school girls have their Sunday head kerchiefs edged with several rows of fancy zigzagged hem stitching in light blue thread. Seen from a distance these hems give the impression of a very simple border print.

47 Other innovations are less visible. Many Hutterite women no longer bother with hooks and eyes. Snaps have quietly take over. Buttons on outer garments are seen as a decoration and have a military connotation for Hutterites. They are a traditional way of indicating one's regiment. In many European folk costumes, as in Scandinavia and the Netherlands, buttons are miniature samples of the gold and silversmith's art: they are often small masterpieces of filigree. In other areas folk costumes feature men's coats with rows of large buttons set so closely together that they are no longer functional. To avoid any temptation of using buttons as personal decoration, Hutterites close their outer garments with hooks and eyes. Men used to make them during the winter from wire with the aid of a small wooden tool, called a template or pattern. The trouble was that not every colony had such a template. Templates were often borrowed from other colonies and often took a very long time to locate. More often than not women had to make do with recycled hooks and eyes from discarded garments. In the early 1980s, a Hutterite lady from a South Dakota colony gave her relative on an Alberta colony the present of a handful of snaps.19 This was a wonderful gift. Not only did she have to hunt through discarded clothing for hooks and eyes, but snaps do not get caught and entangle other garments in the wash as the hooks did. Gone now are the days of broken nails in the attempt to open a hook that became shut during the wash!

48 Another innovation is the "penny pocket," a curved patch pocket. During the last five years penny pockets, hidden under the aprons, are quietly replacing the set-in pockets in the skirts.20 Traditionally Hutterites are not allowed to have patch pockets on their dress. These, too, are seen as decoration and have associations with military uniforms. The shirts of Hutterite men do not feature a breast pocket. Most Hutterites clip their ballpoint pens to the edge of their shirt opening, somewhere between the second and third button, while some sport a buttonhole in the left front of their shirt to accommodate a pen.

49 Looking at the dresses in museum collections, one can conclude that the women's dress of the Hutterites of the 1870s was a very modest version of the nineteenth-century east German or central European folk dress. The intricate details of construction and the variety of patterned prints in the older dress are probably more a reflection of the incredible exuberance of nineteenth-century European folk dress than of an initial toleration of elaboration by Hutterite spiritual leaders. In the course of more than one hundred years the form of the dress was gradually simplified by elimination of all vestiges of nineteenth-century construction methods and the adaptation of twentieth-century sewing techniques and materials. By making caps and aprons of the same fabric as the blouse and dress, the outward appearance of the Hutterite dress is simplified. However, practically all fabrics have a pattern: even the solid coloured dress has floral sprigs in the damask weave. While clothing accessories are no longer embroidered with elaborate monograms and dates (the laundry is marked with small letters and numbers at an inconspicuous place) young girls may put their name on a cap or kerchief in liquid embroidery and mothers give their children's dresses a finishing touch with machine embroidered hems.

50 A comparison of the clothing in museum collections with that worn today, and interviews with older Hutterite women and fabric suppliers reveal that, in contrast to general belief, Hutterite dress is not static. In the course of more than a hundred years in North America Hutterite dress has gradually simplified. Like women's dress in the society at large, Hutterite women's dress has become simpler, both to make and to take care of. While this transition has been dramatic in high fashion, the changes in Hutterite dress have been small, gradual and, for the uninitiated, hardly noticeable. The same social and technological trends that make waves in worldly fashion, cause ripples among the Hutterites. Perceptive collectors of Hutterite material are aware of the subtle changes. It will be interesting to see how current trends, such as an increased access to new developments in fibres, fabrics and sewing techniques, and a constant evaluation of these small adaptations within the framework of the spiritual guidelines will shape Hutterite dress in the coming decades.

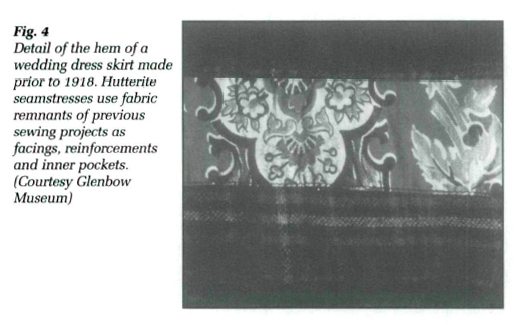

APPENDIX A

The author gratefully acknowledges the extensive instruction and the assistance of Mrs. Sarah J. Tschetter of the Cluny Colony, and her helpful suggestions upon reading the draft of this article. The author also acknowledges the informative hospitality of Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence and Susanna Hofer of the Erskine Colony, Mrs. Barbara Hofer of the Ridgeview Colony, Miss Susie Tschetter of the Tschetter Colony, Mrs. Lydia Hofer of the Rosebud Colony, and Mr. Peter K. Hofer of the Ridgeland Colony, all in Alberta, as well as Ms. June Hofer, of Raymond, Alberta. She thanks Mr. Peter Waldner and his family of the Fairville Colony, Bassano, Alberta, and Mr. and Mrs. Mike and Maria Maendel of the Suncrest Colony, Tourond, Manitoba, for their helpful suggestions upon reading the draft of this article, as well as for their informative hospitality. The author also acknowledges the financial assistance of the Alberta Museums Association and the Joy Harvie Maclaren Scholarship (Glenbow Museum, Calgary), which made it possible to travel to Manitoba and to visit the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature and several colonies in rural areas of Alberta and Manitoba.