Articles

Tangible Demonstrations of a Great Victory:

War Trophies in Canada

Abstract

In many communities, the war trophies that were captured by the Canadian Corps during the Great War have fallen into disrepair. In the years immediately following the Armistice in 1918, German artillery pieces were highly prized by communities across the country as symbols of the gallantry of Canadian soldiers and of the victory that had been achieved on the battlefields of Europe. Their subsequent history was checkered. Many fell victim to the financial constraints of the Depression and others were consumed in the scrap drives of the Second World War. Since 1945, with public interest focussing instead on weapons which had been used by Canadian troops, war trophies have completed their transformation. Once living parts of the community, they have moved into the museum as objects for study and exhibition.

Résumé

Dans de nombreuses localités, les trophées de guerre capturés par le Corps d'armée canadien pendant la Grande Guerre se sont peu à peu dégradés. Au cours des années qui ont suivi immédiatement l'Armistice de 1918, les pièces d'artillerie allemandes ont pris beaucoup de valeur dans toutes les régions du Canada, comme symboles de la bravoure des soldats canadiens et de la victoire remportée sur les champs de bataille européens. Par la suite, elles ont connu des hauts et des bas. Bon nombre ont subi le contrecoup des contraintes financières de la Crise et d'autres ont été victimes des collectes de rebuts de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Depuis 1945, le public s'intéressant plutôt aux armes utilisées par les troupes canadiennes, ces trophées en sont arrivés à l'étape finale de leur évolution. Jadis intégrés à la vie des collectivités, ils reposent maintenant dans les musées comme objets d'étude et d'exposition.

1 War trophies can still be seen in parks, school-yards, and on street corners across Canada, although they are becoming more and more difficult to find. In Apsley, Ontario, a German heavy machine gun squats disconsolately in front of a tiny Legion hall. In Frank, Alberta, two machine gun stands, the barrels having long since disappeared, flank a field gun atop a crumbling concrete platform. In front of the high school in Madoc, Ontario, a German light mortar sits beside the town's war memorial; a few feet away, incongruously, there is a children's play area.

2 In the 1990s, these relics of the Great War have fallen into disrepair — they have become victims of vandalism, neglect and natural decay. They are often regarded as hazards to children and eyesores to passers-by; the original intent behind their display has long been forgotten. But in the years immediately following the Armistice in 1918, war trophies were highly prized by communities across the country as tangible reminders of the Great War. Sir Edmund Walker, a member of the committee struck to distribute the trophies, wrote that they would "express the feeling of the people regarding the war for many years to come."1 Indeed, the trophies said much about the way Canadians viewed the First World War, and their history offers a telling insight into the place that the Great War has occupied in the national consciousness.

3 July 1918 found the troops of the Canadian Corps at rest around the city of Arras in northern France. Behind them were three years of blood-letting, at Ypres, the Somme, Passchendaele, and countless other places; ahead was the drive eastward, past Cambrai and towards the Rhine. On 26 August 1918, after a successful operation west of Amiens, that drive began as two divisions of the Canadian Corps opened the advance that would later be known as Canada's Hundred Days. The first leap took the troops past Monchy-le-Preux (the graveyard of the Newfoundland Regiment in 1917), all the way to Dury; by 4 September, Canadian soldiers were positioned on the west bank of the Canal du Nord. On the 27th, the push began again, through Bourlon Wood and Cambrai, and on 1 November, Valenciennes was liberated. Eight days later the Corps sat around the Belgian town of Jemappes, not far from Mons. That city, the site of the first clash between troops of the Empire and Germany in 1914, fell on the night of 10-11 November.

4 Press and popular accounts of that final, three-month advance are revealing. For the first three years of the war, such accounts measured gains in yards, either of the trench captured or the depth of penetration into enemy lines; this was the only way that success could be measured.2 It may have been a war of attrition in the strategic sense, but the number of casualties inflicted on the enemy could only be guessed at and, consequently, made very unsatisfactory reading for the general public. Territorial gains, on the other hand, allowed exact accounting; they could be expressed specifically, in terms that the average civilian could understand. However in 1918, another dimension began to creep into these accounts. Successes were still measured by the yard but, increasingly, Canadian gains were also expressed in material terms; contemporary histories frequently listed not only the ground gained, but also the number of German soldiers taken prisoner and, even more importantly, the number of guns captured.3

5 There are various reasons for the emphasis on the capture of weapons. First, it offered an even more tangible way to gauge success. The gain of 1 000 yards (914 m) of ground could be imagined by the average person, but its significance might not be as clear; one might wonder about the value of the territory that had been taken, especially if casualties had been heavy. The capture of 100 machine guns and 50 artillery pieces, however, was very different. Not only could such weapons be easily imagined, but they could also be lined up in neat rows and photographed for publication in Canadian newspapers (Fig. 1). Some civilians might have questioned the value of retaking a few acres of French soil, but the value of capturing guns was obvious: they could no longer kill Canadian boys.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 The emphasis on captured ordinance reflected the importance of field pieces in the military mind. Because they served as a unit's colours, "saving the guns" assumed an importance equal to saving the flag; no sacrifice was too great to prevent the enemy from capturing artillery pieces. This notion, imported to Canada from Europe, had lost none of its significance by the turn of the 20th century. During the Boer War, three members of the Royal Canadian Dragoons (including Lieutenant R. E. W. Turner, Chief of Canada's General Staff at the time of the Hundred Days) received Victoria Crosses for saving their guns from a vastly superior Boer force at Leliefontein in November 1900. "Never let it be said that the Canadians had let their guns be taken!" shouted Turner after being wounded in the action.4 During the First World War, "saving the guns" still carried tremendous resonance, and contemporary accounts are full of stirring deeds of heroism performed to prevent the capture of an artillery piece; more than one Canadian observer stated proudly that the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) had never lost a gun.5 Given that these accounts placed such emphasis on Allied troops saving their guns, it follows that the capture of enemy guns by Canadian troops was just as important because it demonstrated, perhaps as well as anything else, their triumph over a tenacious enemy.

7 Finally, captured weapons symbolized the shift from trench fighting to open warfare that had culminated in the Hundred Days. The most that could realistically be hoped for in trench warfare was to capture some rifles and a few light machine guns or trench mortars; the larger prizes were behind the enemy's reserve lines, well out of reach. When the advance was quicker, as it was during the Hundred Days, these weapons became vulnerable. Heavy mortars, field guns and heavy howitzers, positioned well behind the front lines, began to fall to the Allied advance. The capture of these big guns signified that the tide of the war had turned; the stalemate of the trenches was over and Canadian troops had played a major role in ending it.

8 Whether or not all of these notions occurred to him at the time is unclear, but Arthur G. Doughty, the Dominion Archivist, certainly realized that captured guns could have a relevance after the war. Not surprisingly, Doughty was concerned first and foremost with preserving a record of Canada's war effort, which he viewed as crucial to the country's national development; the Great War saw Canada casting off "the shackles of tutelage" and moving "into the full glory and strength of nationhood." Such an event, of course, would have to be suitably memorialized at home: "When our tears are dried and Time has assuaged our sorrow, then shall we seek for memorials of this momentous event and regard them as our ancestral heritage."6 For Doughty, the most obvious memorial lay in the paper records of the CEF, and in 1916 he travelled to the war zone to ensure that provisions were being made for their safekeeping. Upon reaching France, however, he became acquainted with something else that could memorialize the sacrifice of war and thus become part of the nation's "ancestral heritage": captured war trophies.

9 Aware of their value as symbols of Canada's war effort, Doughty first made application to the War Office for trophies in July 1916. The process for securing them, however, was not that simple.7 In theory, all captured material was to be deposited in the British ordnance stores at Croydon, where any guns which could be used against their former owners were converted. According to an agreement of July 1917, everything else became the property of the government whose troops captured it. For a time, the backers of the National (later Imperial) War Museum in Britain asserted a right to choose the best pieces for its collection but the Dominions, especially Canada and Australia, made it clear that they expected to retain the right of first refusal on any guns captured by their units.8 Under the arrangements in place, Dominion officials travelled to Croydon at frequent intervals to inspect the guns in the stockpile and make preparations for the immediate shipment overseas of those which they claimed.

10 After the Armistice, the work of collecting trophies was pursued more aggressively by H. Beckles Willson, the novelist and Canadian War Records officer, who managed to attach himself to Canadian Corps headquarters and spend the better part of 1919 scouring the former battlefields for relics. Willson was certainly keen, but he could have been a little more discriminating in his choice of relics; included in the "trophies" he shipped to Canada in July 1919 were the iron font of La Clytte church, a quantity of broken tiles, some empty sand bags, various pieces of carved oak, a Singer sewing machine, and nine pairs of 1914 issue German Army breeches.9 Though Willson had been warned in 1916 that the "distinction between war relics and loot is at times fine," his final report suggests that he frequently crossed that line. He described visits to a number of former German officers' clubs and barracks which he carefully combed (or perhaps plundered) for swords, uniforms, helmets, badges, books and battle pictures.10

11 Doughty was obviously most interested in seeing that this material, the captured guns as well as the souvenirs amassed by Willson, be preserved as historical artifacts to be housed in the contemplated Great War museum.11 In the interim, however, it could perform other vital functions, specifically as a focus for fund-raising campaigns and to instill patriotism. Some local officials realized this at an early stage. A member of the Parks Board in Waterloo, Ontario, a district with a sizeable German population, asked the Department of Militia and Defence in Ottawa for a captured artillery piece to display; the board member thought it important that the German settlers around Waterloo see a gun that had been captured by the Canadians from "the army that had so long been the pride of their race."12 The government also offered captured heavy artillery pieces as prizes in the 1919 Victory Loan drive, to be awarded to the communities that made the largest contributions to the campaign; it was hoped that this would provide an incentive for donations, which were becoming increasingly difficult to solicit.13 It seems to have had the desired effect; campaign organizers in Prince Edward Island, where the gun was won by Summerside, claimed that the prize had been responsible for at least a third of the total pledges received.14

12 Other leaders had grander schemes in mind. In September 1918, Newton Rowell, the leading Liberal in the Union government, suggested to Prime Minister Robert Borden that there be a nation-wide display of Canada's war trophies, "having regard to its educational and inspirational value to the great mass of our own people." Small exhibitions had been mounted in Halifax, Saint John, Montreal and Baltimore in late 1917, and in 1919 a major national tour was organized.15 It passed through the western provinces, stopping in Winnipeg, Moose Jaw, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver, and in the summer of 1919 was featured at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) in Toronto. The collection spent the first anniversary of the Armistice in the Hamilton Armories. The range of material on display was impressive, although not all of it had been captured from the Germans. For the modest admission price often cents, visitors to the exhibition could see a tremendous variety of artifacts, including the fuselage of Victoria Cross-winner W. G. Barker's Sopwith Snipe, German commander-in-chief Field Marshal Erich von Ludendorff's telephone and a model of the cottage in which his headquarters had been located, a host of official war photographs — the largest over 15 feet (4.5 metres) wide, a rat-trap built for use in the trenches, and the door of the Ypres post office.16

13 Only a fraction of the war relics shipped to Canada from Europe could be put on display, though. By April 1919, Canada had received 107 field guns, 19 trench mortars, 248 machine guns and 629 miscellaneous pieces, as well as a special allotment of 5 000 rifles and bayonets and 5 000 empty brass shell cases of various sizes.17 Once all of the material had reached Canada, it amounted to nearly 4 000 machine guns, over 900 field guns, howitzers, trench mortars, dozens of aircraft, 10 000 rifles, and train-loads of other material, most stored in four cities. Seventy-five guns were in Saint John, and 106 field guns and howitzers sat in a Montreal freight shed. At the CNE grounds in Toronto, Doughty had stockpiled 165 artillery pieces, 1 600 machine guns, five aircraft and a Whippet tank, and at the Ottawa exhibition grounds, 221 artillery pieces, 349 trench mortars, 2 200 machine guns, 5 000 rifles, and 3 000 shell cases.18

14 The problem was what to do with it all. Some of the material was earmarked for museums which had been proposed in various communities. The county of Brome, in Quebec's Eastern Townships, was granted an assortment of relics including posters, weapons, glass from the cathedrals at Soissons and Arras, a part of the first Zeppelin downed over England, and strands of barbed wire, all of which was housed in a special building dedicated to the dead of the war. In Saskatchewan, provincial officials concocted a similar but much more ambitious plan. In April 1919 they announced a competition to erect a building beside the provincial legislature which would serve as a memorial to the province's dead and a museum for Saskatchewan's war records and trophies. A Regina realtor, Lieutenant-Colonel James McAra, was assigned to collect exhibits, and he and museum architect Percy Nobbs tried to squeeze everything they could out of Doughty. The Dominion Archivist wanted to keep much of the material for the proposed national war museum, but he eventually relented and gave Saskatchewan more than its share of captured weapons, including a 210-mm howitzer, a torpedo and warhead, Zeppelin parts, and aerial bombs. Most of this went into storage in the powerhouse of the legislative building until the museum was ready.19

15 Doughty probably expected such requests from potential museum curators, but he may not have counted on the desire of communities across the country to own a piece of the Canadian Corps' victory. Requests for trophies began to reach Doughty as early as 1916, but the demand burgeoned while the collection was touring Canada. It seemed that every community wanted something. Some towns merely requested the loan of a small collection to put on display at an agricultural fair or a celebration for returned soldiers,20 but most were interested in a more permanent arrangement, preferably involving a large and impressive weapon. The reeve of West Lome, in southwestern Ontario, requested a trophy "provided it was not one of those little fellows." The town council of Dundas, Ontario suggested asking the Minister of Militia and Defence for four small mortars and two machine guns to add to its memorial square.21 St. Peter's Church in Duncan, British Columbia wanted two small enemy guns to flank its memorial cross. The Rutland Branch of the United Farmers of B.C. also requested two guns, to be placed in front of Rutland District School.22 Requests came from all quarters, from parks boards, churches, schools, local patriotic societies, and every other conceivable interest group.

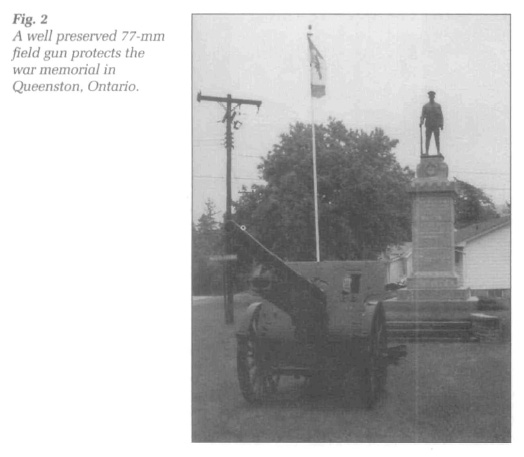

16 Distribution of this material was entrusted to a board consisting of Doughty, Brigadier-General E. A, Cruickshank, director of the General Staff's Historical Section until 1920, and Sir Edmund Walker. Using a complicated formula of allotting the type, calibre, and number of weapons based on a community's rate of enlistment, the committee eventually parcelled out the best of the war trophies to all provincial capitals and hundreds of cities and towns. In the distribution, each provincial capital received six guns, four trench mortars, 12 machine guns, and 100 rifles.23 A number universities received German aircraft, which they were to use for educational and exhibition purposes; unfortunately both Acadia and Mount Allison lost their aircraft to fire in the early 1920s.24 The students of the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) in Guelph, Ontario were disappointed to receive only a 105-mm light howitzer, which they christened Amelia, and "a miscellaneous pile of junk alleged to have been at one time machine guns, rifles and equipment." The school's magazine wondered how communities that had sent overseas only a fraction of the men that OAC had could get away with demanding a heavy howitzer or a set of field guns.25 Many of these communities sited their trophies beside the local war memorial26 (Fig. 2). In some places, like Farnham and Granby, Quebec, Weymouth, Nova Scotia, and Douglas, Manitoba, they were placed on pedestals to become integral parts of the memorial. Regardless of its size and destination, every piece was accompanied by a letter from Doughty: "These trophies, which have been declared the property of the people of Canada, are sent to you with the understanding that proper care will be taken of them and in taking them over, it is understood that you agree to this condition."27

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 217 The hundreds of communities which proudly mounted their trophies in parks, schoolyards and on street corners did so to ensure that the deeds of Canada's citizen-soldiers remained firmly in the public consciousness. Newspaper columns, public addresses, sermons and published accounts of the post-war years constantly stressed the necessity of keeping alive the memory of Canadian exploits on the battlefield, and every conceivable opportunity was taken to do so. War histories and service rolls were compiled, cenotaphs were erected, Armistice Day was observed, and schools, streets, mountains, and even new-born babies were named after people and places associated with the war. Prominently displaying weapons captured from the enemy in battle was yet another way to perpetuate the memory of Canada's wartime sacrifices. Robert Borden spoke of them serving as "constant reminder[s] of the great achievement of that mute, glorious Canadian army, asleep in Flanders Fields."28 Doughty's board itself considered the trophies to be "lasting mementoes which will represent the bravery as well as the sacrifice of her [Canada's] noble sons." They would become "exhibits of Canada's prowess in the Field and prove to those of later days that her sons of the Great World War were men worthy of the name Canadian."29 For Victor Odium, who commanded the 11th Infantry Brigade for the last two years of the war, field guns, trench mortars, and machine guns could occupy a position in the community as "physical and tangible reminders of the courage, fortitude and skill of Canada's sons."30

18 They were reminders of more than just the valour of Canadian soldiers, however. They reminded Canadians that the war had seen the triumph of the Allied cause. One Ontario newspaper editor called the captured guns "tangible demonstrations of a great victory,"31 victory not simply for the Allied armies but for the Canadian way of life. In his 1919 popular history of the war, Colonel George G. Nasmith observed that Canada's triumphs on the battlefield proved that "the individuality of a peaceful population, strengthened and developed by loyalty, was better fighting material than a military ridden country could ever produce." The same year, Manitoba Free Press editor J. W. Dafoe agreed, seeing strong evidence in Canada's response to the war that "we have been building our nationhood on sound lines."32 The display of captured German weapons offered tangible proof of these notions. A heavy howitzer in a Manitoba park or a trench mortar in front of a New Brunswick town hall demonstrated that Canada, a peace-loving nation of citizen-soldiers, had triumphed over the militarized and Junker-ridden Germany.

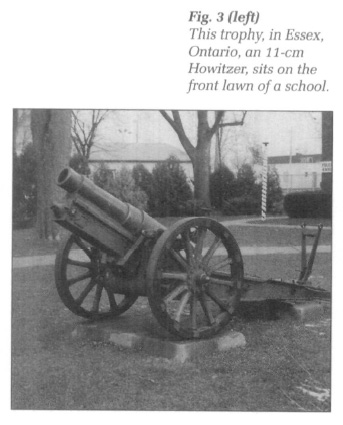

19 In this context, a war trophy was strongly didactic: it served as an object lesson that right would always overcome might. This fact explains the placement of trophies in front of churches and schools, something that would be inconceivable in the 1990s (Fig. 3). For the church which interpreted the war in spiritual terms as a triumph of Christianity, a captured trench mortar would stand as testimony to the fact that the forces of darkness had been vanquished. When the war was interpreted in temporal terms as a triumph of civilization, that same mortar, placed in front of the local school, testified that barbarism had been turned back in 1918. A committee in South Oxford, Ontario elected to place its gun on the school grounds "where it will be ever present with the children to impress on their minds at this most susceptible age all the sacrifices that Canadian soldiers made to not only the present but future generations of Canada." A branch of the Children's Aid Society had the same thing in mind, intending to place a trophy on the grounds of its new children's home where it could be "inspirational to the rising Generations."33 In each case, the trophy instructed observers in the moral issues of the Great War and also taught them the need for vigilance if Canadian values were to be preserved.

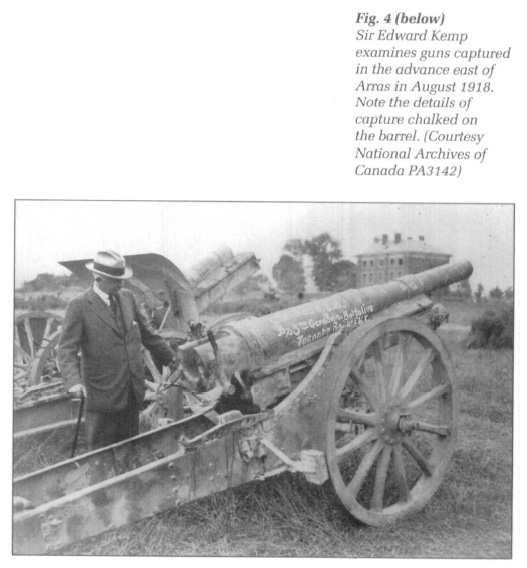

20 It would be a mistake to see the display of war trophies as a modernist recognition of the primacy of the machine in 20th-century warfare; rather, it was an affirmation of the traditional assumptions regarding conflict. The heavy artillery piece which dealt death from miles away was one of the most potent symbols of technology's potential to transform war into a series of anonymous and random deaths; the shell bursting suddenly miles behind the front lines and killing for no apparent reason became a common motif in post-war memoirs. As a war trophy, the same artillery piece symbolized precisely the opposite. Each trophy was carefully identified as to the place, date and circumstances of its capture; the lineage of a gun was crucial.34 The Toronto Daily Star pointed out that Canadians were not interested in just any trophies, but only in guns which had been captured by specific units in specific engagements (Fig. 4). As the editor put it, they wanted "the things our men took at the point of a bayonet...when some fierce day was won."35 The details of capture were important because the trophies became historical documents, much like a Victorian battle picture by Lady Elizabeth Butler or Richard Caton Woodville. They encouraged the observer to see battle as a rational process with identifiable participants and a clear outcome. Furthermore, it was a process in which the individual soldier emerged superior to the engine of war. The family viewing a German trench mortar in rural Saskatchewan need have no fear that a frightening age of machine-made war had dawned. The very presence of the gun in their local park proved that man had triumphed over machine.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 421 By the mid-1920s, the best trophies in the collection, or at least those most suitable for public display, had been parcelled out. Doughty had already requested from the War Office another supply of artillery pieces to meet the immense demand, but this ran out quickly and many communities had to do without. The captured material that remained, primarily bayonets, shell casings, pieces of weapons, and other miscellaneous items, was of little value according to Doughty; he did not even think that it could be given away as souvenirs. Instead, he suggested melting it down and forging a decorative column to be erected outside the war museum once it was constructed where at least the rusting relics would have an aesthetic function.36

22 In the end, Doughty's advice, perhaps given somewhat facetiously, was heeded. By 1934, most of the captured material had been moved to unsecured storage facilities in Ottawa. Because these buildings were occasionally broken into, the hazards were obvious: German rifles and ammunition were there for the taking, and many of the shells were still filled with explosives.37 To address the problem, an Order-in-Council established the War Trophies Disposal Board, consisting of Doughty and officials from the Department of National Defence, to examine the remaining 40-odd tons of trophies, catalogue any pieces that were suitable for what would later become the Canadian War Museum, and arrange for the disposal of the rest. The engineers, service corps, signals, the RCAF, and the Royal Military College had the pick of anything they could use, and the rest was separated for disposal. The wooden parts, like rifle stocks and wheels, were burned, and everything else was melted down into ingots to be used by any community group that wanted to turn them into a war memorial.38

23 The war trophies that had been distributed proved to be as vulnerable as those that had not. The artillery pieces were not built to withstand years of exposure to the elements without regular care and maintenance, and physical deterioration started taking its toll. Officials from Military District #11 kept a careful watch on British Columbia's war trophies, but by the early 1930s those in Vancouver were becoming unsafe. The Board of Parks Commissioners reported that two children had been injured while climbing on the guns, and that on Hallowe'en Night in 1932 one piece was dragged some distance from its base; a wheel broke off and the gun was left to rest in the mud on one axle. Eventually, all of the trophies were collected and turned over to the Vancouver Exhibition Association, which offered them a home so that they would be available for display purposes.39

24 The situation was the same across the country. In 1934, the Ottawa Journal pondered the fate of a gun at the junction of Wellington and Somerset Streets but could find no good use for it. "[The war trophies] are ugly masses of rusty iron less useful than almost anything else in the world," wrote the editor. He thought they might be turned into ploughshares, but noted that there was little use for these either during the Depression.40 The province of Saskatchewan, having shelved its plans for a war museum because of the cost, also had to find a place for its sizeable collection. The largest items, a 210-mm howitzer and a naval gun, were placed on the grounds of the legislative building.

25 It would be a mistake, however, to see this neglect as part of a growing feeling against war in Canada. Certainly some Canadians criticized the display of war trophies, just as they criticized the observance of Armistice Day, the influence of veterans' organizations, and the teaching of history in schools. These critics were in the minority, however. Attendance at Armistice Day ceremonies grew steadily through the 1930s, communities continued to erect war memorials, although on a smaller scale because of fiscal restraints, and war books and movies (only a fraction of them in the anti-war genre) continued to attract large audiences. Not even the continued interest in the war, however, could withstand financial pressures, and the neglect of the trophies most likely lay in the simple economics of the Depression era. Municipalities on the brink of financial ruin because of skyrocketing relief costs simply did not have the money to ensure that trench mortars and field guns received a thorough cleaning and a fresh coat of paint on a regular basis.

26 In 1939, the era of deterioration came to an abrupt end and the war trophies again began to serve a vital national purpose. That purpose, though, was very different from the didacticism of the 1920s. In the legendary scrap drives to collect surplus metal for the war effort, attention inevitably turned to the trophies of the previous war. Indeed, there was a certain amount of poetic justice in using a field gun captured from the Kaiser's army to forge an artillery shell to use against Hitier's troops. As a result, many trophies met an ignominious but patriotic end. Most of Saskatchewan's collection, including the big guns on the grounds of the Legislature, was melted down for the war effort. A total of $278.21 was raised through the sale of the scrap. The guns in West Lome and Guelph met a similar fate; in all, roughly 20 per cent of the trophies were designated as salvage and scrapped during the Second World War.41

27 After 1945, the trophies of the Great War resumed their slide into neglect, accelerated by the fact that they were now obviously anachronisms. Society no longer operated under the essentially 19th-century assumption that it brought honour to a nation to display weapons captured from its enemies. Technology was no longer foreign to warfare, and there was no further need to assert the superiority of the soldier by displaying machines of war that he had captured. Instead, the technology of warfare was embraced and celebrated; it was no longer man against machine on the battlefield, but man working in concert with machine. The howitzer and machine gun became as respectable as the lance and sabre had once been. Consequently, it became the practice to display weapons which had been used by Canadian troops, since this demonstrated the strength of a war effort that combined Canadian soldiers with Canadian-made (or at least Allied-made) weapons. Parks across the country are now dotted with Allied weapons of the Second World War, from anti-aircraft guns to artillery pieces to aircraft.

28 Overshadowed by Lancaster bombers and Sherman tanks, the remaining Great War trophies face an uncertain future. The fate of the guns awarded to Hamilton, Ontario is perhaps representative. In July 1920, the city proudly accepted delivery of five captured artillery pieces: three 77-mm field guns, one of which had been converted to a naval mounting; a 105-mm light howitzer; and a 210-mm heavy howitzer, one of only nine brought to Canada. They were distributed to parks and other public places around the city; one of the field guns, for example, was sited on the grounds of Memorial School, which had been opened in 1919 as a memorial to the city's war dead. They rested in their respective locations for decades but by the 1960s time and the elements had taken their toll and city administrators began to consider moving them. As a measure of how neglected the guns had become, however, many questions surrounded them. Local officials were not even sure whether one of the 77-mm field guns belonged to the city or to the Steel Company of Canada, to whose property it had been moved.42

29 Eventually, the decision was made to collect the guns at Dundurn Park, the home of the 210-mm howitzer since 1920 and the site of the city's military museum. In 1978, the guns were moved, with the exception of one 77-mm field gun, which had deteriorated to such an extent that only pieces of it could be saved. The move, however, gave only a short lease on life to the guns, for they were still exposed to the elements. The 210-mm howitzer, the jewel of Hamilton's collection, was especially vulnerable; because of road alterations, it now sat beside a major thoroughfare and was exposed to salt spray from the road for part of the year. By the early 1980s, the howitzer had deteriorated so much that it had to be fenced off to prevent injury to curious passers-by. Realizing that all of the guns would dissolve into rust in a matter of years if left where they were, military museum officials began to search for another home for them. No Canadian museums were able to offer the guns sufficient protection from the elements, however, so the city finally arranged to send the 210-mm howitzer to the Liberty Memorial Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, which had pledged to spend $25 000 on restoration and then place the gun in its climate-controlled display hall. When the news got out that the gun was leaving the country, a minor public outcry erupted; people suddenly remembered that the howitzer, neglected for decades, was part of the nation's heritage. One Hamiltonian said he would rather see it fall to pieces than leave Canada. Eventually, a local boiler works stepped in to perform the necessary repairs and in November 1987 the refurbished howitzer was re-sited in Dundurn Park. The repair work, however, was limited to a coat of paint and some spot welding and before long the decay began again. Once again, museum officials searched for a home for the pieces and, this time, were more successful. The field guns have been moved to indoor storage facilities in Hamilton to await restoration, while the howitzers have been accepted by the Canadian War Museum, where restoration is currently underway.43

30 Once seen as a centrepiece of a community's collective memory of the Great War, the few remaining captured weapons now occupy the same space in the public consciousness as the Victorian city block, the 19th-century worker's cottage, or the boarded-up Edwardian railway station. Few people express any interest in either their origins or their existence until they are threatened. Then it is suddenly remembered that they form part of Canada's heritage, and feverish efforts to preserve them are put in motion. Sadly, these efforts are, more often than not, unsuccessful. The war trophies, however, have the advantage of being more portable than a cottage or railway station, and can be transported to a safer location with relative ease. As Hamilton's case shows, the greatest obstacle to their survival can be well-intentioned but misplaced local sentiment. In this regard, it is wise to recall Doughty's original instructions to the recipients of the trophies, that they belonged to the people of Canada and that the communities that received them were only acting as custodians.

31 Over its lifetime in this country, the war trophy has been something of a barometer of Canada's perception of the Great War. During the war, it fostered patriotism and enthusiasm; immediately afterwards, it was a source of local pride and a symbol of what the war meant to Canadians. Ten years later, it became a casualty of the Depression but in 1939 was mobilized for another war. In 1945, however, it was confirmed as an antiquated relic, an anachronism from a bygone age. Now, in the 1990s, the war trophy has completed its transformation. Once a living, vital part of the community, it has now been taken into the museum as an object for exhibition and study. Like the Great War that brought it to Canada, the trophy has, for most people, ceased to be a part of the national fabric and has become a fascinating reminder of some far-off, distant time.

The audior wishes to drank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for financial support, and Bernard Pothier and Cameron Pulsifer for their assistance with archival material.