Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

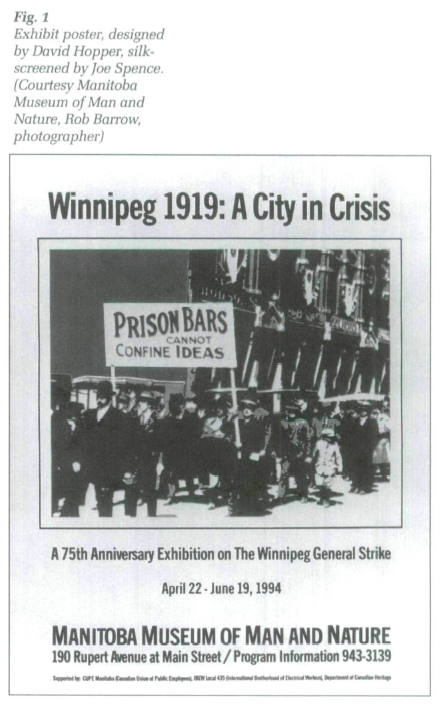

Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, Winnipeg 1919: A City in Crisis. A 75th Anniversary Exhibit on the Winnipeg General Strike

1 Few Canadian cities have a single dramatic event such as the Winnipeg General Strike rooted so firmly in their collective memory. While historians have long debated the consequences of the six-week standoff between 30 000 workers and Winnipeg's social and economic elite, Winnipegers have never doubted that the event shaped the character, social geography and political culture of their city. As I grew up in Winnipeg, the strike occupied a vague place in the city's remote past. Nevertheless it was perceived to be somehow connected to Winnipeg's poor but proud "ethnic" North End, to the presence of mansions along Wellington Crescent, and to the continuing penchant of Winnipegers to elect NDPers and even Communists from the North End, and Liberals and Tories from the South. In some undefined way, the strike made Winnipeg what it was.

2 Not surprisingly, the seventy-fifth anniversary of the strike was both commemorated and contested in Winnipeg. The labour movement used the occasion to celebrate an inspiring moment of solidarity in its history through an array of events: parades, picnics, a one-person play, a short video, trade union educational classes, and the support of this exhibit by at least two unions. The business community studiously ignored it. This apparently instinctive reaction was captured in the "Winnipeg 1919" exhibit at the Museum of Man and Nature (Fig. 1) in a 1950s CBC television program that featured a member of labour's strike committee and a local businessman who had served as a member of the anti-strike "special" police in a face-to-face debate. The former presented the strike in a positive light as a key moment in the slow accrual of labour's rights; the latter as a shameful event that permanently undermined the city's economy and was best forgotten. Given the analogous reactions seventy-five years after the event it is difficult to disagree with local Communist Jacob Penner's 1950 comment about the immortality of the Winnipeg General Strike that greeted visitors to the exhibit.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 Familiarity with the past provides both challenges and opportunities for public history. The photographic record of the strike is well known, as is the narrative of events: the vote, the dispute over the "By Authority of the Strike Committee" cards, the arrests, the police attack on "Bloody Saturday," and the trials. The exhibit does, however, challenge visitors to think about the past differently. In part, this is achieved through the exhibit's design; no single narrative of the strike is presented. Many of the more than two dozen archival photo panels examine various aspects of the city's social history underlining, by implication, the many sources of tension that led to the explosion of 1919.

4 In restructuring the narrative, the exhibit shines in three areas: its portrayal of ethnicity, gender, and social class. Immigration and ethnic diversity are hardly a new story, but the presentation of Eastern European immigrants as key subjects in this history is new, or at least being resurrected. In reaction to the accusations of an "alien" conspiracy against British-Canadian values made by opponents of the strike, the strike's historians have rarely highlighted the active roles played by immigrants during the strike. This was facilitated by a photographic record that presents Eastern European immigrants simply as the impoverished occupants of North End slums or the quaint and harmless members of immigrant societies. Artifacts on display, however, present a much wider image of groups pursuing collective goals through mutual aid and radical associations.

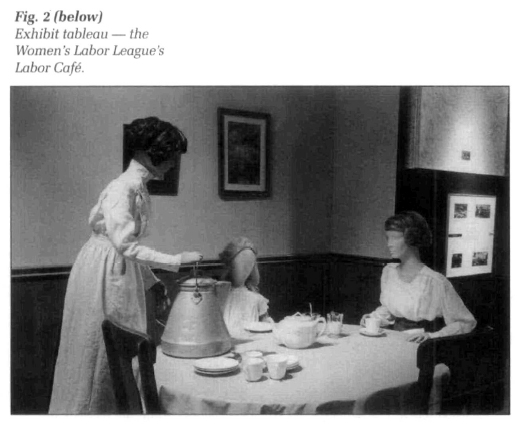

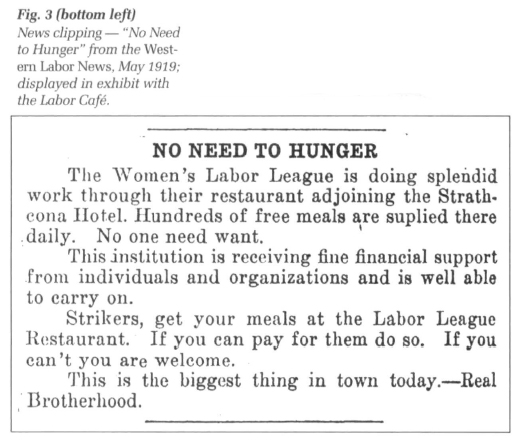

5 The tendency of archival and photographic records to ignore the role of women has been effectively countered by two life-like tableaux with mannequins. One is of symbolic importance and shows a woman walking away from her telephone switchboard — the action by 500 women workers that marked the start of the strike. The second is a display of the "Labor Café" operated by the Women's Labor League to provide free meals to strikers, especially to young, poorly paid women (Figs. 2 and 3). Together, they provide a sample of the different kinds of roles women played in the strike. A third tableau depicting a woman strikebreaker pumping gas, indicates that women were active on both sides during the strike.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

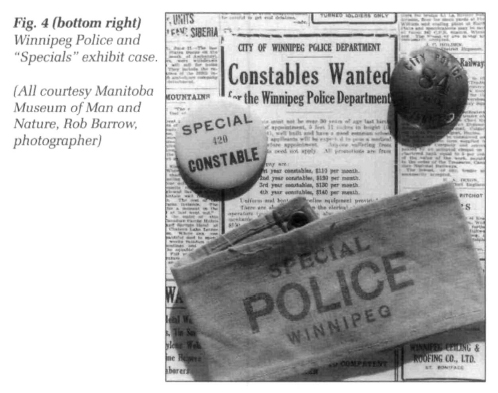

Display large image of Figure 46 Most gripping was the exhibit's presentation of another gendered activity. The "Specials," the vigilante-like volunteer police that replaced the regular force that was dismissed because it was deemed unreliable by the municipal government, were all men (Fig. 4). The display of their artifacts, mostly billy clubs and badges, is a chilling reminder of the threat of official, or semi-official, violence through the strike and not just at its denouement on Main Street on June 21st. Accompanied by a tableau depicting the swearing in of a Special, the dynamic of class, and especially the defence of employers' privileges by potentially lethal means, is effectively demonstrated.

7 Not all aspects of the strike received as full treatment. One product of the pictorial history of the strike has always been the assumption that working-class and North End were synonymous. But the backbone of the organized labour movement were the British-Canadian skilled workers who were widely scattered in the West End, Elmwood, Weston (which is depicted here) and Fort Rouge. Their collective role (as opposed simply to that of their leaders like Bob Russell) is not explored to any extent. This is the case, I think, because their contribution to the strike was largely ideological.

8 Ideas travel most easily through text and spoken word. Tableaux, artifacts and photographs reflect their influence but cannot easily articulate the passion and the nuance of the battle of ideas that escalated into physical confrontation in the spring of 1919. As carriers of the rapidly evolving ideas of militant, radical unionism, skilled workers at their workbench, union lodge, or at their kitchen table, are difficult to present. Where these ideas do surface — the "Citizen's Committee of One Thousand" panel shows both an application to join the One Big Union and a "Citizen's" advertisement attacking the movement — they are only explained in the sketchiest of manners. Indeed, the exhibit format does not lend itself to a discussion of ideological distinctions.

9 Nevertheless, ideas determine our understanding of the strike. Recently, historians have criticized the tendency to dismiss the issues behind the strike as straightforward "industrial relations" differences over union recognition and wages.1 It now seems apparent that the out-pouring of support for the metal trades and building trades workers had its source in a combination of widespread anger and hope. Why else would 30 000 workers risk so much to come to the defence of so few of their fellows? They had lost confidence in their employers and politicians and, however vaguely, hoped that a new kind of social order would emerge out of the sacrifices of both the war and the strike. The strike, then, was much more than a conditioned response to poverty and discrimination; it was driven by a set of ideas that suggested that such conditions need not continue. It is an important historical insight that people in the past thought imaginatively and acted on the basis of their notions of justice.

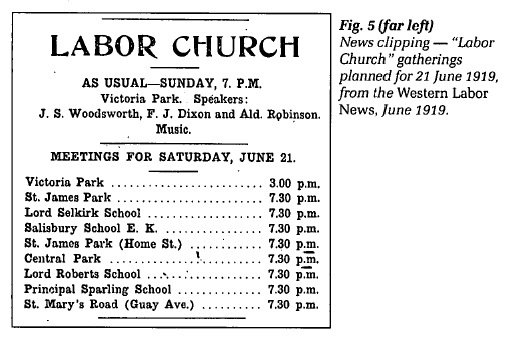

10 This has long been a problem with the way past working-class activism has been presented and this exhibit goes as far to overcome this as any that I have seen. It was, for instance, a revelation to me that nine Labour Church meetings had been planned for June 21st — Bloody Saturday! (Figs. 5 and 6). Workers did not just fight, they discussed. The very attractive poster for the exhibit, in stark black and red, focussed not on the violence on Main Street, but on the importance of the ideas behind the strike.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 611 I was able to spend a couple of hours in the exhibit over the course of two days, and, on several occasions was met by people wanting to share insights, memories, or opinions about Winnipeg, the strike, and the exhibit. In most cases, it was to assert the authenticity of various images of the city presented in the exhibit or to claim part of this history as their own. It was a connection that museums too rarely are able to make. One concern that I had about the substantial amount of text on several panels was assuaged by watching several people painstakingly reading. The assumption that some museums seem to have made, that a literary public has disappeared, seems to be misplaced. Perhaps the variable is simply the extent to which people want to know more about what they are seeing; certainly this exhibit struck such a chord.

Curatorial Statement

12 Spring of 1994 marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike. This dramatic confrontation was of greater magnitude than any struggle to that date in Canadian labour history. It affected virtually the entire population of the community, sparked sympathy strikes across the country, and attracted international attention.

13 The issues over which the strike was fought grew out of the ethnic and class conflict that permeated early Winnipeg and continued to influence the city's later development. The history of Winnipeg cannot be fully grasped without an understanding of the strike, its roots, and its legacy.

14 Yet, like other aspects of working class history, discussion and debate about the Winnipeg General Strike has been confined increasingly to the realm of academia. "Old timers" and union leaders might remember the conflict but students may, or may not, learn about the strike, and are unlikely to be introduced to this history as adults.

15 The seventy-fifth anniversary presented a fitting opportunity to promote a greater public awareness of the events of 1919. The Manitoba Labour Education Centre took the lead in organizing and co-ordinating a range of commemorative activities in Winnipeg and in Brandon, Manitoba. Staff from the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature contributed to this work; however, the Museum focussed primarily on its own seventy-fifth anniversary project — the development of the exhibit Winnipeg 1919: A City in Crisis.

16 While many of the events organized by the Labour Education Centre were directed toward a labour audience, the Museum exhibit was aimed at individuals of all ages and backgrounds. Special programs were developed for high school students, university audiences, and the general public.

17 The exhibit was intended to encourage visitors to learn more about the strike and to engage its audience in a discussion of the strike's legacy. It aimed to heighten awareness of some of the lesser-known aspects of the strike, like the role of women and the importance of radical politics in segments of Winnipeg's ethnic population. The sub-themes of class, ethnicity and gender were given special focus and, rather than being treated separately, were integrated throughout the display. As well, by incorporating the Museum's considerable labour and social history collections with more traditional sources of historical information, the exhibit sought to demonstrate the variety and wealth of interpretive materials that exist.

18 The exhibit included several distinct elements which were intended to complement and enhance one another. Archival photos and interpretive copy were arranged in a series of panels along the outer walls, establishing the major themes and telling the story of the strike. Dozens of photographs were included — some well known, others newly discovered and offering fresh insights into the conflict.

19 Next, a rich selection of artifacts, works of art and archival documents, which both illustrated and expanded upon the ideas raised in the wall panels, were displayed nearby. Documents included publications from the Strike Committee and its opposition, the Citizen's Committee of One Thousand; court records; police and fire department records; newspaper clippings, and so on. In addition were publications in Yiddish, Ukrainian and Italian, from Winnipeg's flourishing ethnic press. Personal recollections, like the diary of a returned soldier, also were included.

20 Early twentieth-century trade union regalia from Winnipeg locals, including a rare, hand-painted parade banner, made a vibrant addition to the display and offered some idea of the pride and sense of tradition associated with such organizations. Artifacts representing the radicalism and social and economic significance of many of Winnipeg's fraternal organizations were also included. One prominent item was a twenty-five foot-long building sign from the Kossuth Sick Benefit Association, named for the Hungarian revolutionary leader.

21 The themes of the exhibit were fully expressed with the materials described above. However, to achieve a more powerful impact and reach a wider audience, it was decided to include seven lifelike tableaux portraying the people and events of the strike. Visitors to the exhibit were greeted by a group of strikers parading down Main Street, in front of a wall-sized image of City Hall, carrying banners reading "Strike or Starve" and "One Big Union." Elsewhere, a member of the Women's Labor League served lunch to a woman striker and her child at the Labor Café. Another setting re-created a well-known photo of "Special" constables swearing an oath of allegiance after the regular police were fired for their support of the strikers. The tableaux proved to be captivating for audiences of all ages and helped to draw viewers to the more detailed information presented elsewhere.

22 The exhibit was further enhanced with an archival CBC video featuring two programs in which Winnipegers remembered and hotly debated the significance of the strike. This, too, attracted considerable attention.

23 Finally, two cases — one filled with archival documents and the other with published histories of the strike — were integrated into the exhibit near a table equipped with "hands-on" binders containing photocopies of archival documents. Visitors were thus invited to undertake their own research, and to leave their comments in a guestbook placed nearby. Remarks made about the exhibit in the notebook, and to Museum staff present, were overwhelmingly positive, and confirmed the belief that visitors had little, if any previous exposure to this part of their history, but believed it to be of great importance both historically and in terms of present-day concerns.