Articles

Snippets of History:

The Tintype and Prairie Canada

Abstract

The tintype is one of the ubiquitous forms of photography which has for the most part recorded the existence of the common person. A process first introduced in the mid-1850s, it is still in occasional use today. These collodion and later gelatin-based images on thin, blackened, iron sheets were customarily sent through the mail to sweethearts and family. Though popularly called "tintypes" they were never made on tin. This paper reviews the fascinating history of tintypes, and describes how to identify them. The author also dispels some persistent myths about this "humble" process and describes its circumstance in western Canada. Preventive care is briefly mentioned.

Résumé

Le ferrotype est une forme de photographie omniprésente qui a en grande partie permis d'enregistrer pour la postérité l'histoire des gens ordinaires. Le procédé, qui a vu le jour vers le milieu des années 1850, est encore utilisé à l'occasion aujourd'hui. Ces images sur emulsion de collodion et, plus tard, de gélatine, réalisées au moyen de minces tôles de fer noircies, étaient couramment envoyées par la poste aux amis de cœur ou à la famille. Même si on les appelle « tintype » en anglais, ces clichés n'ont jamais été faits d'étain. L'article que voici raconte l'histoire fascinante des ferrotypes et explique comment les reconnaître. L'auteur y met fin à certains mythes persistants sur ce « modeste » procédé et décrit comment il s'est développé dans l'ouest du Canada. Enfin, l'article mentionne brièvement comment conserveries ferrotypes.

Introduction

1 The tintype was immensely popular in North America from the late-1850s onward. To a much lesser degree tintypes were also popular in Europe, although European interest generally lagged by a decade. The use of collodion chemistry to make tintypes gave way to gelatin emulsion dry metal plates by the early-1890s. This genre of photography survived because of its continued use by street photographers until the mid-twentieth century. Ferrotypy is the proper technical name for this photographic process. The words "ferrotype" and "tintype" are terms often used interchangeably to describe the light-sensitive plates, and "tintypist" to describe the photographer. These and other terms proliferated throughout the popular language and in commercial and technical publications (Appendix A). Street photographers in Central and South America still practise ferrotypy today. This paper uses the convention ferrotypy for the process and the layman's term tintype for the resulting image. For historical accuracy, quotes and the endnotes retain the contemporaneous vocabulary.

2 The tintype, like the ambrotype, was a particular application of Frederick Scott Archer's wet-collodion process.1 A japanned (i.e., blackened) sheet of thin iron was substituted for the ambrotype's glass support. These metal plates were coated with collodion, sensitized and immediately exposed in the conventional "wet plate" manner. A photographer or "tintypist" would sensitize a plate, make the exposure, develop and fix the plate, and cut it apart with tin shears. A variety of formats, ranging from postage-stamp size "gem" tintypes (approximately 1.5 x 2 cm) to the large "double whole" plates (21.5 X 33 cm), were produced. (It is technically inaccurate to classify a tintype by a "plate" dimension as many are not only snipped in uneven portions but their edges were subsequently trimmed. Nevertheless popular nomenclature prevails.) The most common sizes included "one-sixth plate" and "carte-de-visite" (approximately 5.5 X 9 cm).2 Some tintypists enhanced the image by applying assorted water- or oil-based colours to its surface.

3 Tintypes have been produced in the studio, by the itinerant photographer and by the general amateur. All provided on-the-spot delivery to customers or friends. Subjects, often dressed in their Sunday best, some with fixed and glazed expressions or stiffening muscles and backs braced by assorted support clamps, could hardly wait for the magic emulsion to harden. Tintypes became the vacationers' keep-sake, the Sunday strollers' momento. Ironically the tintype, which so permeated the lower working class of society, rarely outlined the social and other problems with which this group struggles. Rather the tintype image, largely through the use of studio props, created an ersatz lifestyle and does little to further our understanding of the working-class life. This suggests that it is wise to remember that photographs cannot stand alone as interpretative statements about the past, any more than can other primary sources.

4 Very few publications have discussed in any detail and accuracy the development of the tintype.3 This paper covers the development of the process and a brief review of its introduction into western Canada; the camera, the studio and itinerant photographers; the tintype image as a keepsake and adornment; identification, preventive care and storage.

The Tintype and Canada's West

Collodion Ferrotypy

5 In 1852 and 1853 Adolphe Alexandre Martin, a college professor in Paris, presented to the Société d'Encouragement and to the French Academie des Sciences two Compte Rendus in which he outlined processes to make direct positives on glass and on tinned plate or galvanized iron.4 His reports had little impact on a nation probably still enamoured with the daguerreotype and certainly with the new albumenized paper processes. The publication of The Collodion Process on Glass in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer had no bearing on Martin's work. Independently and apparently unaware of Martin's work, Hamilton L. Smith, professor of natural science from Bambier, Ohio, was carrying out similar work with a seminary student, Peter Neff, Jr., during 1853-54 and then independently in 1855. In 1856, on the advice of Neff, Smith applied for and subsequently obtained U.S. Patent 14,300 (February 19,1856), to make "ferrotypes."5 The patent suggested that the black Japan needed to coat the metal plate (before one can make it light-sensitive) could also be applied to other solid surfaces, including "leather, fibrous materials and rubber." The "ferrotype" was also patented that same year by William Kloen and Daniel Jones in England.6 Europe, with its predilection for social classes, showed no interest in the "lowly" process. Peter and William Neff eventually purchased the patent rights for the manufacture of the plates.7

6 In the spring of 1856 Neff opened a gallery in Cincinnati and promoted the new process through a pamphlet entitled The Melainotype Process, Complete.8 By October 1856 another young American innovator, Victor Moreau Griswold, had applied for two patents to improve on the process.9 Soon-to-be competitor Griswold criticized the popular name "tintype," calling it "senseless and meaningless," pointing out that "not a particle of tin, in any shape is used in making or preparing the plates, or in making the pictures, or has any connection with them anywhere, unless it be, perhaps, the tin which goes into the happy operator's pocket after the successful completion of his work."10 By 1863, tintypes were purchased for as little as two cents each and still proved profitable! Oliver Wendell Holmes remarked that "pauperism itself need hardly shrink from the outlay required for a family portrait-gallery. The 'tintypes,' as the small miniatures are called — stannotypes would be the proper name — are furnished at the rate of two cents each!"11 (Ironically, Holmes' "stannotype" might refer to iron-black colour but its root stannous refers to any compound containing tin!)

7 By early 1857, continued experimentation resulted in improved resistence and assorted hues (blue, green, red and chocolate) to the japanned surface.12 The japan or varnish was made with linseed oil, asphaltum and sufficient umber or lampblack to give the desired shade, boiled, then tested for consistency — thinned with turpentine if necessary — and eventually brushed onto the metal, and oven-dried. Other possible ingredients included mastic, lac or copal varnishes and other shades of colouring matter. Ironically in a technologically inclined nation the mental conservatism of the photographers themselves doomed the effort to sell the assorted (non-black) hues nationally. There was even the reported manufacture of white enamelled plates susceptible to being used as a negative!.13

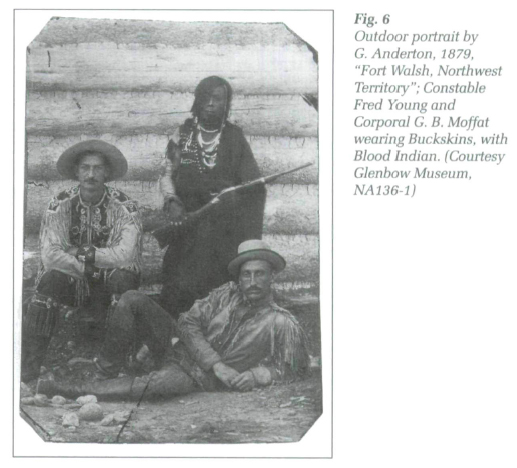

8 That same year the technique of ferrotypy reached the eastern Canada market.14 Just as the ambrotype was winning public favour, the tintype became a popular style of portraiture and remained so for three-quarters of a century.15 Some "established" studios, both in Canada and in the United States looked upon the process disparagingly. Mathew Brady, along with many operators, would not permit his New York and Washington galleries to make tintypes.16 Others like William Norman, who was appointed "Photographer to the Queen," promoted albumen photographs but had no reluctance to operating in tintypes.17 Maritime photographers appear to have been very adept with the wet-collodion process. Not content with ambrotypes, tintypes and cartes-de-visite, advertisements suggested novelty photographs on cloth, mica and leather.18 The novelty and the inexpensiveness of the tintype captured public interest throughout Canada — in the West as well as the more populous East. By August 1860 The Nor'Wester advertised tintypes and ambrotypes as well as the prevalent paper photographs. An itinerant D. R. Stiles had opened his "Ambrotype Gallery" at Mr. Charles Caviliers, St. Boniface, "for a few days" and also offered to take tintypes.19 The Red River Portrait Gallery owned by Barnard and Parton offered all the latest "likenessess" including the "melainotypes."20 (See Appendix A.) Photographic advertisements did not appear again in The Nor'Wester until November 21, 1864 when Joseph Langevin opened his "Photographic Gallery" in the Red River Settlement.21 From his ledgers we see that he also provided tintypes, and was doing a lucrative trade in photography.22 Nevertheless the expression "not on your tintype"23 reflected the dubious quality of an image.

9 From the mid-1850s to the early-1860s Neff and Griswold were the sole manufacturers of tintype plates to the continent.24 In an early effort to promote their greater use, samples were sent to nearly all of the dealers in photographic goods in the United States and quite probably in Canada as well — with good results. Edward M. Estabrook, a strong proponent of the tintype, pointed out the "obvious" advantages over its predecessor the ambrotype. In the ultimate sales (and preventive care!) pitch Estabrook wrote:

10 Whether through pettiness or excessive competitiveness, both manufacturers Neff and Griswold threatened each other with lawsuits. Griswold cut his prices as he improved production of his plates. Neff countered by freely making available the necessary licenses to practise ferrotypy.26 One possible reason the practice was not immediately (i.e., 1856-58) adopted by the photographic fraternity was that it had been patented, making it not only necessary to buy the plates at monopoly prices, but also to buy the right to use them. Hamilton Smith himself "apologetically" requested a $20 fee back in 1856. Rates later ranged from $25 to $300 for a "room-right license."27 At one point a merger was proposed between Neff and Griswold but was eventually rejected.28

11 Failing to recognize early the weakeness of their geographical location both men eventually saw the manufacture of japanned collodion plates switch from their Ohio bases to the increasingly industrialized cities of Newark, New Jersey and New York.29 Towards the end of the Civil War other companies had joined the fray, among them: Holmes, Booth & Hayden; Willard & Co.; and Anthony & Co. acting as distributing agents to several manufacturers. A division of The Chadwick Leather Manufacturing Company of Newark, New Jersey, manufactured tintypes, but there is no evidence they also made pannotypes or leather sensitized for images.30

12 The stereoscope, a new and popular form of entertainment with its life-like views, was eagerly sought during the Civil War. Two slightly different views are paired in such a manner that, when viewed through a stereoscope, a three-dimensional or solid view appears. No Civil War views were produced as stereographic tintypes. The lack of contrast (though not the clarity) of the image could not compete with existing paper stereographs. Neither could the simple (and commercially viable) procedure of printing multiple, transparent negatives onto paper. Only a few stereoscopic tintypes were produced, mostly in the late-1860s and early-1870s.31

13 Horace Hedden or his son H. M. Hedden, soon after the formation of the Ph[o]enix Plate Company, Newark, New Jersey, brought out the "Chocolate" plate after obtaining a patent on March 1, 1870.32 This plate would temporarily renew the interest in ferrotypy. By August 1871 an English patent had also been obtained.33 In a world bent on new and improved techniques (such as the commercial manufacture of tintypes) most did not realize or care about chronic illnesses to the respiratory and nervous systems — ultimately leading to death.34

The Open Prairie

14 The late-1870s and early-1880s saw small settlements appearing on the Prairies. This had become a rapidly changing region. The North West Mounted Police was established and the land survey system was created. In the 1870s the native peoples were largely confined to reserves and a government for the Northwest Territory was organized. The "West" was now ready to receive immigrants although the expected flood of immigration would not come until the railroad was completed and the more actively promoted land south of the border had been filled.

15 As always, itinerant photographers were drawn to these new frontiers. By 1879 the Winnipeg directory listed three photographers in that city; two at Emerson, Manitoba; and one each at Portage la Prairie, Manitoba and Battleford and Prince Albert in the North West Territories35 — an impressive number for the times. There is no doubt that several of these photographers were itinerant. None are specifically listed as "tintypists" but ample evidence of their work exists. Whether in portraiture or in the recording of scenery, most of these photographers produced images of artistic merit and aesthetic quality.

16 The 1880 N.W.M.P. Commissioner's report from Fort Walsh, Northwest Territory, remarked that "the police force has been stationed here for six years and yet there is not a bona fide set-tier within one hundred miles of Fort Walsh."36 Within the area of present day Alberta, the population reached only 17 500 by 1890.37 With such a small and scattered population, it is no surprise that early tintypists like W. E. Hook, from Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin and T. G. Anderton from the Fort Walsh area, made the circuit of North West Mounted Police forts.

17 Hook's work includes Fort Calgary in the early spring of 1879. He must have been part of an earlier westward trek, via Minnesota-Montana routes.38 Anderton (himself a member of the N.W.M.P. from 1876-79) recorded life at Fort Walsh and vicinity in the late-1870s and very early-1880s. In 1879 he took a discharge from Fort Macleod and shortly thereafter became a "professional photographer."39 As the Fort Walsh men had suffered an alarming number of serious diseases in 187840 it is not inconceivable that Anderton saw a business opportunity and rushed to exploit it; the tintypes could be sent as reassuring news to family back East. He eventually became Medicine Hat's first commercial photographer in 1883.41

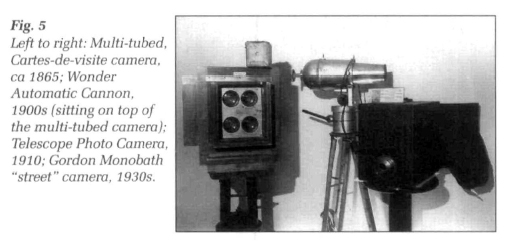

18 Certainly, the existing coach and mail services and routes throughout the territory made travel possible, though not without hardship.42 In 1885 the rapid encroachment of European civilization, symbolized by the railroad, caused the Metis and some of the native tribes to attempt once again to establish their rights to a land rapidly becoming alienated from them. While these events were actively recorded in photographs, few tintypes have surfaced.43

The More Rapid Gelatin Dry Processes

19 While producing astounding results, collodion photography, by its shortfalls (i.e., the need to immediately prepare, sensitize and photograph), encouraged the search for a more convenient means of capturing an image. Popularized ca 1878, the gelatin process on glass or "dry plate" helped greatly to eliminate the collodion wet-plate process. The photographer was no longer encumbered by all the paraphenalia previously required to formulate an image. Commercially prepared glass plates were ten times as fast and consistent! However, it was not until the 1890s that commercially manufactured tintypes using gelatin-silver chemistry became available. As supplies made their way from eastern Canadian centres to the West, the practice of preparing the "old fashioned" collodion tintypes probably lapsed by 1900 in the Prairies.

20 Richard Leach Maddox invented the first practical formula for a gelatin-silver halide emulsion. As early as 1847 others had experimented with sensitized gelatins with varying success. In 1871 Maddox published his work and by 1873 prepared gelatin dry plates were being marketed in England. The following year Richard Kennett introduced the "high speed" pellicle44 and subsequently offered prepared dry plates. Manufacture of the gelatin tintype only came into existence in 1890. Basic emulsion manufacture ("ripened" emulsion) was cooled to a jelly, cut into noodles, washed of excess chemicals and byproducts, reheated (altering the chemistry) and finally coated onto a continuously moving roll of the sheet metal support (i.e., the plates) and cut into standard sizes and packaged.45 In England's post-industrial social climate, ferrotypy gained popularity, especially with the introduction of dry "ferrotype" plates by Ladislas Nievsky in 1891.46 Development took from eight to twelve seconds in hot weather, twelve to twenty seconds in mild weather and up to sixty seconds in the cold. After fixing (1:5 ratio hyposulfite/water) for ten to thirty seconds, the plate was quickly rinsed and then dried. Varnished, it gave the appearance of having been produced by the wet-collodion process. This was followed by the development of the "street" camera, with built-in processing facilities removing the need for a portable darktent. Both contributed to the third and final resurgence of the tintype, especially in North America.

The Prairie from 1870 to 1930

21 By the turn of the century the populations of Manitoba and the Northwest Territory had risen impressively; Manitoba from 12 000 in 1871 to 108 000 in 1886, and 255 000 in 1901; the Northwest Territory farming population, which measured in the hundreds in 1871, rose to 31 000 in 1885 and 164 000 by 1901.47 The itinerant and studio photographers recorded the people's story. Countless tintypes and stories still lie hidden among the pages of photo albums. In other cases the tintypes are gone but the mysteries remain — like the lost tintype of the Fathers of Confederation from Calgary City Hall, or the set of nine half-plates taken of Calgary at the turn of the century, evidence of which surfaced fleetingly in 1993.48

22 In 1886 the Chautauqua, an American temperance phenomenon, established its first Canadian roots in Wolseley, Saskatchewan. By 1917 the western Canadian circuit included Lethbridge, Taber, Cayley, Nanton and Macleod.49 The commercially manufactured gelatin emulsion called "photo-button" tintypes were in general use between 1890 to 1930. These were the earlier presensitized plates, now the cut into circular coins and packaged. Some were rimmed with an aluminium or "white metal" jacket. Most were sold with the camera and a variety of promotional accessories. The "Duz-it-all" Photo Button Camera, distributed in 1911 by the Colonial Art Company, Toronto, was free to anyone who purchased "Oleograph [multicolour prints] reproductions of famous paintings."50 The Depression to a large extent brought about the demise of tintypes on the Prairies. Only its successor, the Atrograph or "paper tintype," would make any headway with itinerant photographers after the '30s.

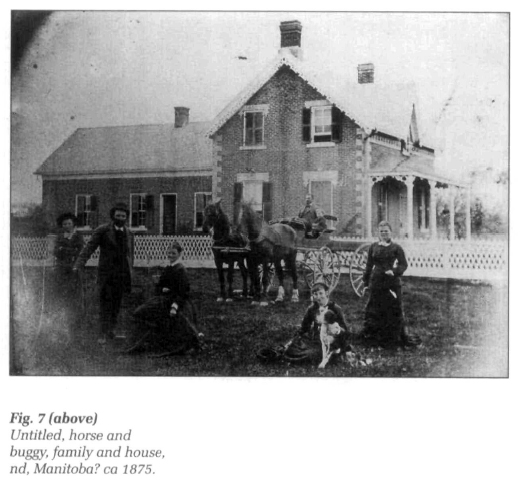

The Camera. "Sit Sir, While I Take Your Pictures"

23 The early cameras consisted of a front box with a lens fixed to a baseboard on which a slightly smaller rear box slid. It was not until 1851 that the principle of the bellows was incorporated into the camera body. Suffice to say that even by the 1860s photographic equipment was still in its infancy. With the introduction of the carte-de-visite craze, many studios owned several camera boxes (bodies) that could be fitted with different lens systems called tubes. The operator could take several simultaneous exposures and single or multiple exposures of one or more subjects, thanks to a sliding, repeating back.51 The most basic tubes were set two by two, two by three, and three by three. Even sixteen by sixteen tube systems are not uncommon. René Dagron, ca 1860, constructed a microphotographie camera which produced a 2-mm-square image! The vertical and horizontal sliding motion of the plate holder combined with the 25-lensed board or tubes would produce 450 exposures on a single collodion plate.52 By the mid-1860s, the ability to produce images in multiples of two or more so inexpensively created tremendous competition for large volumes of business. This became especially useful for tintypes and stereoviews.

24 The portrait lenses used between 1860 and 1872 allowed for a working distance of four to five metres between sitter and camera. The photographer moved the camera to obtain initial focus, with finer adjustment by thumb screw to obtain sharp focus. Multiple lenses were mounted on a brass panel and each lens was individually adjusted for focus, because of the practical limitation (even well into the 1880s) of grinding several lenses for one board to precisely the same focal length. A final refocussing through the ground glass, and the camera was ready for almost any eventuality!

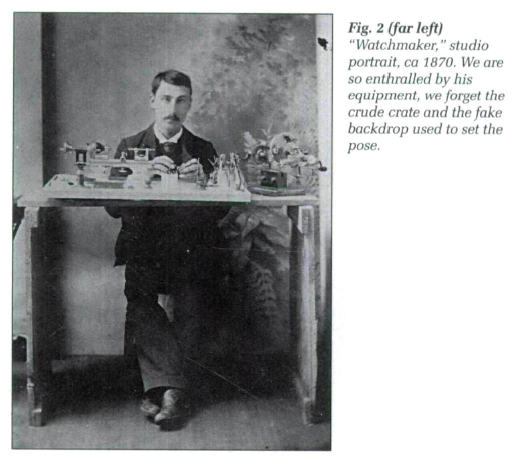

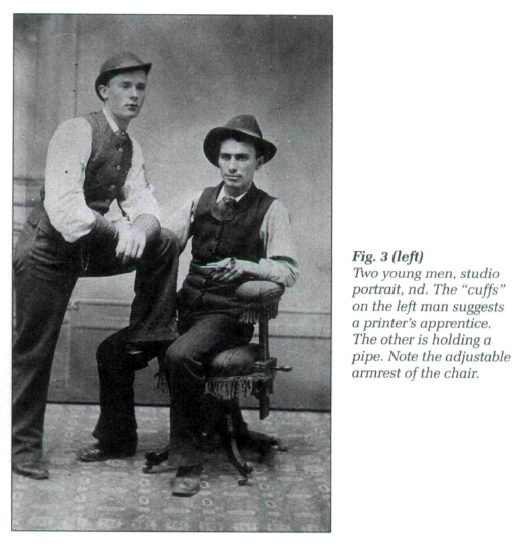

25 Properly immobilized or "clamped," the subject offered little problem; even children provided successful results. On occasion the camera took multiple images of inanimate objects (Fig. 1) for advertising purposes or calling cards;53 or a single image of a proud tradesman such as the "Watchmaker" (Fig. 2). Tintypes were often quickly produced, with little attention to camouflaging the obviously fake background or the extra protruding feet of the headrest stands. Occasionally the studio chair itself became a prop (Fig. 3) and allows us to appreciate its versatility. After they were developed, pictures were crudely separated by means of tin shears or snips and handed over to the patron either as is, possibly varnished, or placed in a card mount or album. Prevalent among Eastern boarding schools and higher educational establishments was the school album with "gems." A full plate of "gem" tintypes was cut, and the images inserted into specially matted pages suitable only for the small pictures. Headmasters and teachers adorned the front pages; students, by class or subject, filled the remaining frames. The practice was in general use between 1880 and the turn of the century.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

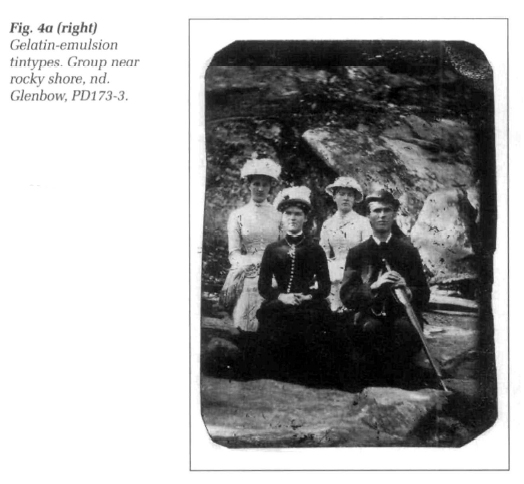

Display large image of Figure 326 With the introduction of the more rapid dry ferrotype processes ca 1890 the tintype camera showed considerable technical evolution and widespread use. The multiple lens camera gave way primarily to the single lense camera. By the turn of the century hand-held amateur cameras such as the "Telephoto" were marketed, while operatorless coin-operated "Automatic Photograph" machines (with built-in flashes)54 could be found at fairs. While by 1900 most automats still produced mediocre results, hand-held cameras produced surprisingly good, though stoic, imagery (Fig. 4a). It was not uncommon for even the outdoor or itinerant photographer to make use of the "flash" powder.55 The use of artificial illumination had existed since daguerreotypy. During early collodion photography, magnesium wire burning reduced studio exposure times to under a minute. The burning of magnesium powder came into general use after 1886, thereby reducing exposure time to mere seconds.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

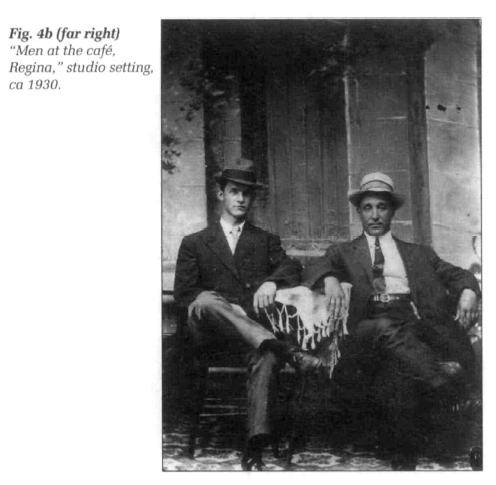

Display large image of Figure 527 By the 1920s the widespread use of the rollfim camera by the amateur greatly reduced the need for street, country fair and beach vendors. The amateur tintypist, with his — now rare — pocket-sized amateur camera, and travelling studios (Fig. 4b) which used larger equipment were at opposite ends of the scale. Most tintypists had by now "converted" to the prevailing paper imagery. By the early-1940s the "tintypist" had more or less disappeared.

28 It is beyond the scope of this paper to review the many manufacturers and models of camera (200-300 for the tintype alone!).56 Representative examples, manufactured over a century, are outlined in Appendix B and Figure 5.

Studio and Itinerant Photographers

29 Some photographers found that life on the road provided a good income. Studio owners sometimes closed their city businesses for the summer and travelled to resorts and small towns, setting up portable studios and darkrooms on the outskirts of towns. Some of them either hired a temporary assistant to cover their studio operation while they travelled, or else sent the employee on the road. In the early years most itinerants used compact, very portable wagons, but citizens occasionally witnessed elaborate horsedrawn wagons or tents.57 Some even commandeered train wagons!58 Notman had darkrooms mounted on sleighs,59 though he is not known to have produced outdoor tintypes during the winter season. Transportation, whether on steamboats along the North Saskatchewan River or on a stagecoach crossing the plains,60 makes for picturesque and strangely appropriate imagery.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 730 Figure 6 is a fascinating tintype taken by an itinerant photographer. The creation of the North West Mounted Police was in response to the need for a sensitive handling of native issues. This need was reinforced in 1869 and 1870 when the Metis showed their power and their unwillingness to be ignored by the Canadian government during the first Riel uprising. The necessity of a police force to keep law and order in the West, and to prevent open conflict between natives and settlers, had been emphasized by both missionaries and military men during the 1860s and early 1870s.61 Nevertheless, from Figure 6 it appears that, like the survey expedition through the open plains thirty years earlier, the photographer chose to record the "triumph of the White man bringing 'civilization' to the West."62

31 Some itinerants managed to have their dark room work done at a studio in the region they visited. They were usually resented by local operators because they naturally competed for business. They paid no rent or utility costs, and could undercut prices charged by established studios. Most chose to set up in the open air. Grass became the studio floor and carpet. The tintype "captured" patterned fabric or painted backdrops, often blurred by the breeze.

32 It is plainly obvious what problems both photographer and subject faced:

33 Once inside his small darkroom the photographer removed the plate from its holder, then adroitly poured a developing solution over its black surface. Almost instantly a creamy white surface trailed the liquid. The image fully materialized, the tintypist then dipped the plate into a fixing bath and finally into a wash. Minutes later he would return to the anxious patron.

34 Studio photographers might encourage the need for "artistic enhancement":

The Image

35 In general, tintypes are not considered to have great value, with the obvious exception of unusual views, activities, and portraits of famous people. The bulk of surviving tintypes feature anonymous subjects (Fig. 7). With few exceptions these are unremarkable in physical presence and visual sophistication. The fact that most early tintypes are portraits reflects the high demand for personal likeness and the relative immobility of the picture-taking process. Their intended function was not artistic originality so much as the subjective and inexpensive preservation of likeness.

36 Light and practically indestructible, tin-types were popular for sending through the mail — hence the names: lettertypes, lettergraphs (see Appendix A). Many, in an effort to emulate daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, were put into similar protective cases. The fashionable photographer tended to sneer at me tintype as being only suitable for those "in the humbler walks of life," but its use continued long after the other direct positive processes had been forgotten. The daguerreotype was no longer in use in Canada by the early-1860s; the ambrotype, after the mid-1870s. Cartes-de-visite and cabinet photographs, together with the tintype, made up the vast majority of portraits from 1867 to the turn of the century. While the tintype never eclipsed any of the aforementioned processes, it outlasted them all (accomodating itself well to gelatin dry plate photography — in particular the Atrograph, which substituted paper blackened on one side for the metal plate. Both processes survive to the present day.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

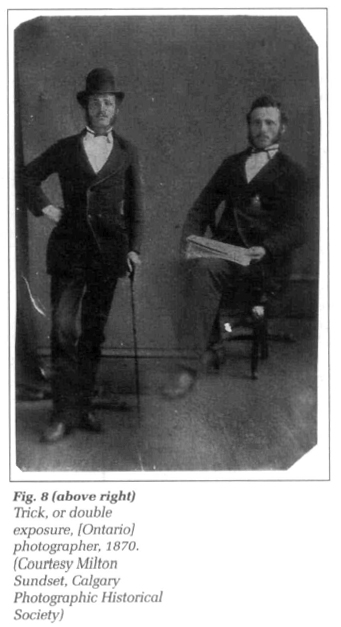

Display large image of Figure 937 For the most part the tintype photographer made no effort to provide elaborate settings or moods. The sitter was usually represented full length to show off crinoline, fedora or walking stick — often studio props. Ironically there are very few with "Western gear." Facial expression was of minor importance. Commonly, only a tiny representation of the poser's head appeared in the picture. If there was any effort from the tintypist, all of his skill and flattery was directed towards the rather rapid arrangement of the pose, as most backdrops were often barren sheets or uninspiring "scenes." We see an increasing use of painted backdrops and props between 1870 and the turn of the century. Most are simple, but there is the occasional "grand" prop such as a buggy and, by the twentieth century, the car (often an itinerant "prop" considering the impracticality of one sitting in a small studio!). Particularly adept photographers occasionally produced "trick" or double exposures (Fig. 8). Unknown (at least to this author) are "spirit" photographs on tintypes and tintype images on both sides of the same plate.65

38 One must not assume that a tintype is automatically the original image. Many studios and itinerants were called upon to copy previously made and cherished photographic keepsakes. Dating a tintype is sometimes hazardous.66 Excluding studio use of right angle "corrective" mirrors or prisms, the tintype, as a rule, is a laterally reversed image. Therefore any tintype demonstrating visually correct wording, shirt button holes, etc., is most probably a copy of another image.

39 Both collodion and gelatin surfaces can readily accept a variety of dry and wet colours (though the author has not come across hand coloured gelatin tintypes). Most tintypes are not heavily retouched — the subjects are often too small to warrant concern. "Artistic" retouching becomes obvious on larger "half" and "full-plate" images. Jewellery-encased images — in lockets, necklaces, brooches, etc., found generally containing "gem" tintypes — were invariably painted over with gilt. Just as with ambrotypes, tintypes may show "jewellery" where none existed. To protect the handiwork the tintypist varnished the dried results. For the early itinerant photographer such varnishes became economical substitutes for protective holders and frames — thereby preventing collodion separation and abrasion.

The Tintype as Decoration and Adornment

40 As souvenirs and keepsakes photographs remain popular. No wonder then that daguerreian, tintype and paper images were often hidden or displayed in such jewellery as lockets, cufflinks, brooches, shirt studs and even suspender clips and tiepins.67 Multi-tubed cameras were capable of mass-producing "gems" which sold profitably. While the majority of anonymous lockets and photo buttons were distributed to friends and loved ones, others describe more illustrious figures. Probably the best known political photo button is that of Abraham Lincoln taken in 1860. Lincoln once said "Brady's photo button and the Cooper Union [speech] made me President of the United States."68 In Canada, Commander Garnet Joseph Wolseley and the 1870 Red River expedition veterans were commemorated with a blue lapel ribbon to which was sewn a matted tintype.69 It is interesting to note that, at least during the American Civil War, tintypes were occasionally competing with the art of silhouette-making.70 Nothing indicates a similar rivalry in Canada. It is not uncommon to find lockets in a collection which have on one side the portrait of a loved one and on the other, a lock of hair sealed under glass. Tintypes were even sealed onto marriage licenses.71 A more sombre application was the tombstone tintype. A current study of Prairie cemetaries indicates that encased photographs, including tintypes, predominate among Eastern European cultures.72

41 Always anxious to pry an extra fee from their enthralled patrons, photographers suggested that they enhance the image with inexpensive brooches, photo buttons, etc. For a few pennies more, the itinerant photographer would also "guarantee" the client's purchase with a coat of varnish.

42 As late as 1900 the Montgomery Ward catalogue promoted novelties like garter buckles with photographs, photo belt buckles, and photo watch charms.73 In 1929 Johnson Smith & Co. of Racine, Wisconsin, offered the Minute Brooch Camera, with everything necessary to make dry "ferroplate" medallions in 60 seconds — all for only $4.95!74

Identifying and Dating Tintypes

43 An unmounted tintype is immediately identifiable by its japanned (i.e., blackened) iron metal plate. A trained eye will recognize the early "thick" plates, assorted stamped manufacturer hallmarks (when present) and even snipped sheets. When placed inside a protective leather or thermoplastic case their identification can be in question. A small, fairly strong magnet held against the centre of the glass will reveal whether the image is a tintype.75 An image found in a "Potter's Patent" frame or similar cartes-de-visite paper/cardboard sleeve holders is invariably a tintype. There are of course exceptions such as Atrographs, "tintypes on paper," produced from the 1900s to the 1950s. With over fifty varieties of sleeves and cards, dating can be very confusing. Use the magnet from the back of the sleeve to confirm the tintype. It may be very tricky to confirm images inside brooches and other jewellery as these are often magnetic themselves! Ask an experienced eye to assist you. Occasionally a tintype will display the manufacturer's stamp along one of its edges (provided it has not been snipped off). These represent the earliest tintype period. Known examples of hallmarks include: "NEFF'S MELAINOTYPE PLATE / Pat 19 Feb 56-"; "MELAINOTYPE PLATE / FOR NEFF'S PAT 19FEB1856" (also with "Pat"); and "GRISWOLD'S PATENTED OCT.26,1856-."

44 Tintypes are still produced today and identifying them as contemporary examples can pose a problem to the untrained eye. The Comminger Brothers tintype photography studio in historic Sherbrooke, Nova Scotia, dresses up visitors in vintage clothes and uses period studio props, head clamps, etc., and chemistry, as in the mid-1870s.76 Identifying the (post-1890s) gelatin-based tintype is best done under a microscope. Under high power a mottled reticulated pattern becomes visible. Reticulation is the result of excessive irreversible swelling of the gelatin of the emulsion layer. The fine ruptures occur during the water rinse, following the developing — a procedure automatically carried out by itinerant or street photographers. Note that a protective varnish on gelatin tintypes hinders identification.

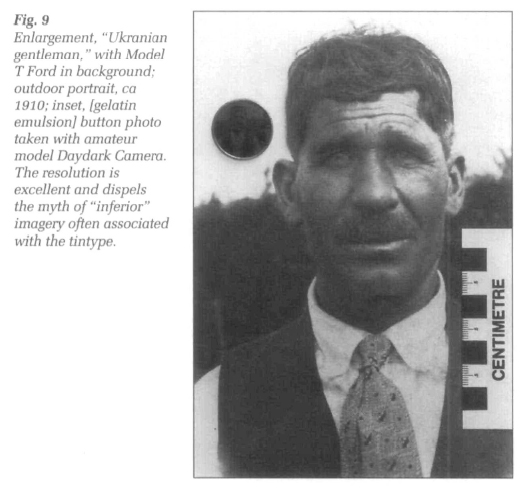

45 Most tintypes suffer from a lack of contrast, the whites are never a sparkling white, but rather a dull grey. In reflected light the image has a creamy appearance because the beaded silver image particles are the correct size and shape to scatter some light back to the eye, rather than absorbing the light to make the image appear black. The more silver present in a given area, the whiter the image looks. Only a small amount of light incident on tintypes is scattered back to the eye, so there is a limit to the brightness of their highlight areas. This limited tonal range is one of the identifying features. This has nothing to do with clarity or sharpness. Enlargement (Fig. 9) clearly shows that excellent resolution can be achieved.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1046 Dating a tintype is a tricky procedure. Most bear no photographer's stamp unless sleeved in a carte-de-visite or Potter's Patent card. Even then the card's back is often unmarked. American tintypes manufactured between August 1864 and 1866 will have a Revenue stamp cancelled by the selling establishment. (In England William Gladstone considered a penny tax in 1864, and so did Benjamin Disraeli in 1868, when it was stated that a penny stamp on roughly five million photographs [the great majority, not tintypes] sold annually would help in defraying the cost of the Abyssinian war.) Tintypes produced before 1870 have a "grey" appearance while those produced thereafter are of a "brownish" or "chocolate" colour. The term "chocolate" is a misnomer since the tintype image may range in hue from light red to near black! The problem is compounded with the introduction of gelatin emulsion tintypes introduced after 1891, as well as the evolution of grey to brown in tones. Except for microscopic examination, only the poser's clothing (i.e. fashion) will give a clue to an approximate date. Tintypes produced in the 1860s have black backing, those after 1870 are brown; the difference resulting from changes in the japanning process used to prepare the sheet iron.77

47 On rare occasions a "cameo" tintype will be found in a collection. These are recognized by the oval-shaped convexity on which the portrait is displayed. The finished picture is pressed with a convex the with no noticeable distortion to the image. Cameo cartes-de-visite date from ca 1868 to 1875. Cameo tintypes probably date likewise. They were popular primarily in North America.

Preventive Care and Storage of Tintypes

48 It is not the purpose of this paper to discuss the conservation of tintypes. Readers should contact conservators of photographs for any concerns; however, a few points are outlined here. Compared with other forms of photography, very little information dealing specifically with ferrotype imagery or its conservation is available.78 The relative sturdiness of the tintype makes it easy to overlook its conservation requirements. What could possibly happen to a sheet of metal?

49 Photographing and recording the image should be the first priority of the collector. Copy procedures are extremely simple and have been carried out for over one hundred years.79 The surrogate image can be handled freely while the original is properly housed for long-term preservation. The copy photograph has untold advantages — it can be enlarged, enhanced, even tinted or coloured. Best of all, it can be replaced.

50 Photocopying a tintype results in a very poor image quality; it doesn't warrant such use. Abrasion can also occur with the collodion or emulsion face down onto the copiers' glass (or any other surface for that matter), and is therefore discouraged. Other problems include the collodion binder commonly deteriorating along outer edges, and the deformation or bending of the plates themselves. Keep all tintypes away from drastic humidity changes and never wet a rusted tintype.

51 Always handle all artifacts, including tintypes, with gloves. Flaking tintypes should be handled with latex, not cotton, gloves to prevent snaring off flakes along the plates' edge by fibrous gloves.

52 Despite earlier prescriptions in the photographic literature, the author strongly advises against any cleaning except under the approval of a knowledgeable conservator. Evaluation of the image will decide whether one should proceed. There is the horror story of the conservator gently dabbing a tintype portrait and finding that the collodion had come off on the cotton swab. Unfortunately the cleaning began on the portrait's face!

53 Rust is one problem which is as likely to occur on either side of the tintype. Cursory microscope work indicates that much exposed rust appears to be hydrous ferric oxides (goethite-limonite assemblies) often with adsorbed water and components of the japanning lacquers (back) or lacquers, photosensitive chemistry and protective varnish (image side). Sandwiched between the metal plate and japanning lacquers, filiform rust expands and migrates causing a separation of the two layers. All of these oxides of secondary origin result from the alteration of the iron plate, through exposure to moisture, air, carbonic or organic acids, and the glues and paper components of the holders themselves. Calcareous papers may conceivably, under correct conditions, help generate rust. Contact a knowledgeable photographic conservator for advice. Do not attempt anything on your own.

54 Ideally any iron artifact should be kept in a pollutant-free environment with an RH (relative humidity) factor below 50 per cent. While low RH is important with tintypes, it should not drop below 30 to 25 per cent if the tintypes are bound with leather, paper or wood. These materials would invariably suffer. Tintypes with flaking collodion binder layers should be identified and housed flat to await conservation treatment. Often this flaking is caused by active corrosion of the japanned iron support. This can be controlled (but not impeded) by storage in a low RH environment.

55 For the encased image, removal may be subject to debate. These images are often in a "pinchbeck"/mat assembly which may require common sense but delicate handling procedures to open.80 It should always be assembled as initially observed. Broken cover glass must be replaced with modern glass of similar thickness. Tintypes are commonly housed in cartouche or "open window" carte-de-visite photo albums. The tintypes were slipped through the base slit in the album. Often the added thickness of a Potter's Patent sleeve makes it particularly awkward to remove. Again, consult the conservator. After appraisal of the situation, the conservator may decide whether removal from an album is warranted.

56 Proper storage materials are essential to long-term preservation of tintypes. Inexpensive archival folders with unbuffered paper are readily available through nationwide archival supply houses, or you can produce your own. Budget allowing, put 4 X 5-inch (10 cm X 12.7 cm) sheets of 2-ply acid-free conservation board into 4 X 5-inch (10 cm X 12.7 cm) polyethylene (or the heavier polypropylene) negative envelopes as stiffeners, and then insert the tintypes. This allows upright, uniform filing and quick visual inspection, and most common sizes of tintypes can be placed in a single file archival box or drawer. Record pertinent information on the backs of the board stiffeners with pencil, not ink! Protect slightly bent plates and "cameos" in a sink mat held together with archival tape in the same manner as loose daguerreotypes or broken glass plates — and store them flat. Use mylar "corners" to prevent movement of the "cameo."

57 A conservator should immediately be contacted if tintypes become submerged in water. Tintypes, wet-collodion negatives and ambrotypes have less than 24-hour stability after immersion and must be archivally cleaned and immediately air dried on an individual basis. Priority is based on image or historical importance.

Final Comments

58 It is commonly repeated that there is little artistry or craftsmanship found among tintype images. Admittedly, the poses are usually stilted and stock; backdrops and props are crudely artificial; and many show garish retouching. However, as memorabilia of sweethearts and families, holidays and vacations, tintypes have nostalgic charm. V. M. Griswold probably expressed it best when he stated:

59 Conservation of photographic material is a relatively new science. There are few old records to indicate early or previous preservation or restoration treatments and written records rarely accompany the images. Among its many treasures the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, holds an inconspicuous one-ninth plate-size tintype with only the bare silhouette of what was once a portrait. On the back of the plate, painted in red nail polish, is the inscription: "Washed off, (19)43, B."82 This short note pays eloquent testimony to the dangers of what seems like a simple treatment of images and the conscientious message to posterity, pointing out the need for careful, knowledgeable preservation. Archive collections generally overlook the tintype. No efforts are made to differentiate between wet-collodion and gelatin-based tintypes. It is hoped that research along those lines will lead to better methods of preventive care.

60 The mostly anonymous nature of tintype subjects, as of most images, is the photograph historian's greatest challenge. Information is quickly forgotten as generations pass on. Prairie Canada has a fascinating history. It is hoped that part of it will be rediscovered through the work of early itinerant photographers. Possibly we will one day find another tintype of John George "Kootnai" Brown83 hiding on someone's shelf.

APPENDIX A

Adamantean (1863+)

Adamantine (from ca 1861-63)

American instantaneous photography (Europe ca 1860) American novelty (Europe ca 1870)

American Photography (Berlin, Germany 1878+)

American process (Europe, ca 1858?)

Anchor*

Atrograph (British, ca 1900-1950, technically a gelatin-based "ferrotype" on black paper)

Bon-Ton pictures (may refer to mounted ferrotypes or albumen prints; uncertain)

Cambria*

Celebrated Chocolate Tint (1871)

Champion

Chapman celebrated O.K. plate (? -1867)

"from Charcoal Iron" (refers to the high-quality English sheet iron used by U.S. Manufacturers)

Chocolate tintype (1871+)

Chromo-Ferrotype (1871+)

Columbia

Diamond (may relate to protective varnish for Adamantean plates)

Egg-shell Ferrotype (ca 1858-1900, considered industry standard)

Eureka (ca 1861-1870)

Excelsior Fallowfleld (ca 1910-1915, Br. commercial plates "collodion emulsion" ferrotype dry plates)

Ferrograph (first mentioned 1856, in Photographic Notes)

Ferrotype (1856-1867, with a resurgence ca 1891)

Ferrotype (1856-present)

Gartle*

Gems

Glossy Ferrotype (ca 1858-1900, considered industry standard)

Helion

Imperial ferrotype

Iron plates

Lettergraphs

Lettertypes

Letter-types

Little Gems

Little Gems

Melainotype (1856-1870?; especially prevalent in Canada)

Melaneotype

Melanograph (1854; early wet-collodion experiments on paper; see Atrograph)

Phoenix (ca 1857-1870+)

Pontimeister*

Portraits sur zinc/Portraits on zinc, de tôle/on sheet, metal (ca 1900 to 1930s, Quebec)

Sheet iron photographs (ca 1898, Maryland)

Silvertype (ca 1860?, H. P. Moore [mfr], N.H.; tradename for copied daguerreotypes)

Star Ferrotype Sunplate (1870-1872, Scovill Mfg Co.)

Tagers Iron, also Taggers Iron (ca 1856, unsensitized plates, American, often stamped)

Tinplate portraits (ca 1900-1930s, eastern Canada)

Tintype (1856-present)

Tintype on paper (ca 1900-1950, q.v, atrograph)

Tiny Gem

Union

Vernis (ca 1861-1862)

Wonder Photo-buttons (1900+, sold in England and U.S.; gelatin emulsion plates)

APPENDIX B

APPENDIX BFerrotype Cameras

- Anthony & Co. Wet Plate Cartes de Visite Camera, ca 1860-1865 (shown in Figure 5 with a recessed four-tube board). Lenses are individually prefocussed. The operator uses the ground glass to frame and focus his subject, swings the viewer to the side and snaps in the just-loaded plate holder. The sheath is opened, the lens cover removed and several moments later replaced. The sheath is redrawn onto the plateholder and the now-exposed plate is immediately developed by the studio assistant while the operator either "chats up" the patron(s) or repeats the process for another set of images. The plate holder could be set to expose two or all four lenses. Septa, or partitions were used behind the lenses near the plane of focus to separate the images from the various lenses and to reduce their overlap.

- The Sears 1909 catalogue offered the Wonder Automatic Cannon Photo Button Machine (initially introduced ca 1893) boasting: "Your picture in one minute for 5 Cents" (Fig. 5). This cannon-shaped device manufactured by the Chicago Ferrotype Company used novelty 2.2 cm diameter (gelatin emulsion) tintype "buttons." Prospective buyers were promised a 400 per cent profit on each sale of a button picture at 5 cents. An extra dime could be asked by putting the picture in a gilt frame that cost less than a penny. The investment for the "Cannon," complete with tripod, 300 plates, 288 gilt frames, and developing powders, was $24.40; the camera sold separately for only $15.00. But the catalogue copy promised, by selling the picture buttons and frames that came with the outfit, you could pay for the whole outfit and pocket $19.40 "in actual money" as well!

- 1910 Telescope Photo Camera (one of several pocket size amateur cardboard cameras) manufactured by the Telescope Camera Co. of New York can almost be called a "detective" or "disguised" camera as it is certainly one of the smaller box type cameras ever marketed (Fig. 5). The instructions claim that the camera "practically works by itself, no knowledge of photography [is] necessary" and "any child can take first class pictures with it." A self-contained cardboard plate holder (shown) is slid over the cameras's receiver slot and a presensitized "button" plate dropped in. The camera slot is closed and the picture taken. Simply invert the camera upside down snug onto the handy (monobath) developer tank (not shown); open the slot again and drop the exposed plate into the tank. The seal made between the tank and camera prevents light from ruining the plate as it develops. A 2-minute development and immediate wash in plain water produced surprising results!

- Monobath "street" camera (Fig. 5), by the Gordon Camera Corporation, New York, ca 1930s. The street photographer was the sole surviver of the genre. "Tintypists" had all but disappeared. Strictly "tintype" cameras were no longer manufactured. Users took advantage of multipurpose street cameras, such as the Gordon camera. The simplified monobadi dry gelatin-emulsion tintype was retrieved from the built-in light-tight storage chamber. The street photographer took your photo. He then manipulated the exposed plate into the pre-made developing bath. Moments later he transferred the stabilized, fixed, tintype from within the camera to a waterbucket usually at his feet. Still wet or quickly dry blotted the street vendor exchanged the tintype for a preset price. The postcard size plate was often snipped into two, doubling the photographer's plate supplies. These cameras were ideally suited for "paper tintypes," i.e., allographs, which eventually replaced the metal plate. By the 1920s the very popular DOP and POP "postcards" (specially prepared developing-out and printing-out papers) had also eclipsed the use of tintypes.

I sincerely thank the following individuals and institutions who allowed me to freely inspect examples from their collections or granted me permission to reproduce photographs in this paper. These include: Lynette Walton, Glenbow Library and Archives, Calgary, who conveniently assembled for my perusal the bulk of tintypes scattered throughout the photographic collections; Suzanne Mclean, Department of Clothing and Textiles, University of Alberta, Edmonton; Milton Sundset and George Tapley, Calgary Photographic Historical Society; Brian Hudson, Edmonton Photographic Historical Group; Bill Maclaughlin, and Mrs. P. Fern Phillips, Calgary. I am indebted to Cynthia Ball, formerly with the Conservation Department, Glenbow, who provided suggestions and moral support in this research. Sincere thanks to historians and authors Dr. Hugh Dempsey and Edward Cavell, Calgary; particular thanks to Dr. Debbie Hess Norris, University of Delaware, Art Conservation Department, for her insight about conservation of early photographic materials; to photography historians Dr. Helmut Gernsheim, Switzerland, and George Gilbert, New York, and to Cathleen LaTendresse, Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, Michigan, for their correspondence. Last, but certainly not least, to Anne Hudson, whose critical review and editing skills are always appreciated. I am very appreciative of Cindy Pawluk, Programs, Exhibitions and Special Loans, Glenbow, for access to word-processor and office space. This paper was presented at the Poster Session, Environnement et conservation des documents graphiques et photogmphiques, Deuxième Journées Internationales d'Études del'ARSAG, Paris, Mai 16-20,1994, thanks to the financial assistance of the Alberta Museums Association. I am very grateful to Dr. Adriana A. Davies, Executive Director, and the AMA, for their continued interest and support in my research.