Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, Chinatown

Curator: Virginia Careless, Bob Griffin (RBCM); David Chuenyan Lai (Guest Curator)

Designer: Alan Graves

Opening Date: November 1992

1 In November, 1992, the Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM) in Victoria, British Columbia, opened Chinatown, a new addition to the sprawling re-creation of Old Town built in the Museum in the early 1970s. The original Old Town was designed to showcase the facades of small shops and businesses with collections visible through plate-glass windows. When it messed with Old Town, the RBCM took on a classic in Canadian museology. Since it first opened, Old Town has spawned mini main streets across Canada, some sophisticated and elaborate, others more haphazard and strictly functional (a good way to show lots of stuff).

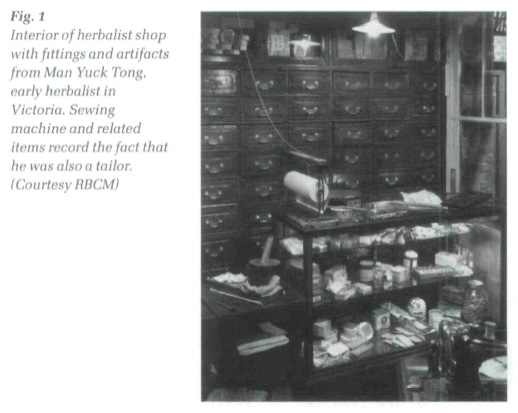

Display large image of Figure 1

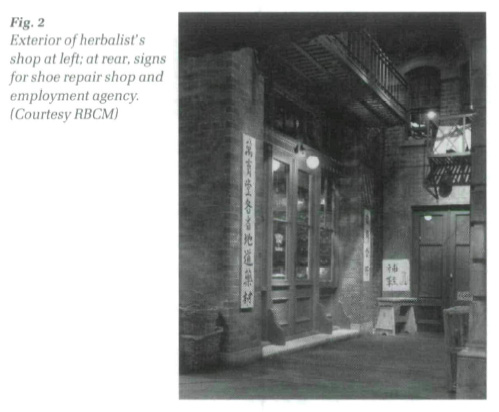

Display large image of Figure 12 Chinatown is a small extension of the original street. The footprint of Chinatown is only 500 square feet, although the exhibit continues overhead in second-storey facades and balconies. Using the same basic Old Town vocabulary of facades, shop fronts and interiors, Chinatown features a herbalist/tailor's shop and an attached kitchen area, while across the street is a food shop. Signs, partial facades, and balconies permit glimpses of living quarters, a shoe repair shop/employment agency, clan association meeting place, gambling club, and restaurant.

3 Chinatown locates a complex, layered Chinese community literally next door to mainstream British Columbia. Visitors enter the cul-de-sac by turning off the main street of Old Town and ducking around a set of stairs. Chinatown gives an immediate, compelling impression of differentness. A subtle sound track of street noise, music and conversations in Chinese animates the space. In front, up and down and all around you is evidence of another time. another place, another culture. The effect is astonishingly complete. It is the result of the combination of meticulous research, long-term collecting, imaginative design and painstaking fabrication.

4 The RBCM relied on well-known historical geographer David Chuenyan Lai as guest curator. As the author of Chinatowns: Towns within Cities in Canada, Lai brought years of expertise in the subject as well as strong connections within Victoria's own Chinese Canadian community.1 The fundamental decision about choices of occupations, choices of building designs, and layout of the streetscape were informed by Lai's body of work on Canadian Chinatowns generally, and Victoria's in particular.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 25 Chinatown's most densely furnished exhibit is the shop of herbalist and tailor Quan Yuen Yen. The RBCM's decision to acquire the contents of the shop in 1982 laid the basis for the success of Chinatown. Long before the exhibit was a real plan, RBCM staff Bob Griffin and Virginia Careless identified the need to culturally diversify Old Town, and collected with that long-term goal in mind.

6 Designer Alan Graves used the tiny space with care and imagination. Mirrors amplify and extend narrow alleyways. The illusion of life-size scale is created through careful sight-line planning. The second-floor windows are more than decoration. Each one is a carefully utilized interpretive opportunity, giving glimpses of living quarters, an ancestral shrine, "cheater" storeys that evaded additional property taxes. The power of the illusion appears to rest as well on the detailing of the fabrication. Even the glass in the shop windows is "old" glass, one of the many parts that add up to a convincing whole.

7 Chinatown's creators set out to convey to visitors a range of feelings, including "curiosity, unease, a sense of being "not at home,' mystery, wonder."2 The exhibit succeeds very well in creating an exotically other world. Possibly the otherness is too extreme, masking at least some of the connections that tied Chinatown and "Old Town" into a symbiotic relationship.

8 Some recent scholarship has emphasized the emergence and maintenance of Chinatowns as a response to the legislated racism of the state. Certainly, in the history of Vancouver's Chinatown, there is ample evidence of the heavy hand of municipal legislation affecting the nature, location and functioning of Chinese-owned businesses.3 Reproductions of business licences and inspection certificates in RBCM's Chinatown would help to suggest the intrusion of the state and the complex cross-cultural relationships at work.

9 The curator chose to emphasize occupations that served the Chinese Canadian community — a herbalist, a grocer and a tailor of Chinese workmen's clothing. The choice underscores the notion of Chinatown as a self-contained and self-sufficient enclave, obscuring the crucial role of Chinese Canadians as workers in mainstream industries. The exterior of the employment agency, for instance, could be used more intensively to present a more complete picture of Chinese Canadian occupational structure (and to create links to the RBCM's other permanent exhibits on canneries and mining).

10 The exhibit's makers used the location of a western-style pharmacy in Old Town near the entrance to Chinatown as an occasion to introduce direct comparison of western and Chinese-style medicine in an interpretive case/ window display. The mixing of exhibit methods — an interpretive case exhibit in the midst of a re-created environment — appears to enrich both.

11 One of the exhibition team's stated objectives was to help visitors "be confident that the exhibit is an accurate reflection of the past," 4Chinatown is unique and ground-breaking in its content; the streetscape will be the image that will come to mind when future generations of British Columbians think of Chinatowns. However, no supplementary material introduces visitors to the basic interpretive issues or presents fundamental evidence for the RBCM's choices. The Museum is still asking visitors to take it on blind faith, to rely on the institutional reputation. Especially when a re-creation is as compelling and spatially and visually successful as this one, visitors deserve the opportunity to question its premises.

Display large image of Figure 3

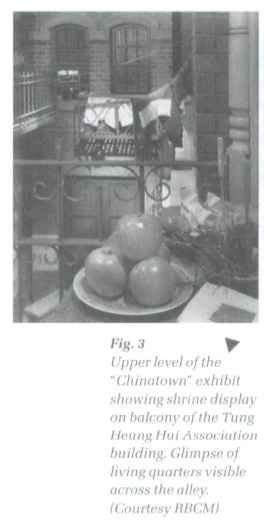

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 412 The greatest problem with Chinatown is that it makes the original Old Town appear slapdash, theatrical, and shopworn. Spaces that were reasonably convincing on their own terms appear by contrast generic and underfurnished. This is a wonderful problem to have: a great exhibit from 1974 is surpassed by a great exhibit from 1993. It is testimony to the fact that museums have improved their capacity for exhibit research, interpretation, and exhibit. It suggests that museums have far from exhausted the potential of that faithful standby - fragments of Main Street.

Curatorial Statement

13 The Old Town Gallery in the Royal British Columbia Museum is basically an exhibit of the socio-economic contribution of early British immigrants to the province of British Columbia from 1890 to 1920. Although Chinese immigrants were and still are the largest visible ethnic minority in the province, and their imprints on its landscape are numerous and significant, their exhibit in the Old Town Gallery consisted of only two window display cases containing randomly selected Chinese artifacts.

14 In the autumn of 1990, the History Unit, headed by Robert Griffin, proposed to enhance the public awareness of the significant role of the Chinese in British Columbia by expanding the Chinese section of the Old Town Gallery. In the following two years, a team of curators, designers, conservators and interpreters, headed by John Robertson, organized the Chinese exhibit which would portray the townscape of a Chinatown in the late nineteeth century and early twentieth, and make it an extension of the Old Town Gallery. The team also planned to seek the participation of the local community in the project.

15 The Chinatown exhibit has three objectives:

- cognitive - to make visitors be aware of the townscape of an old Chinatown, and enhance their knowledge of the early Chinese society in Canada;

- affective - to make visitors experience the feelings of curiosity, mystery and "fear" in strolling through Chinatown at dusk which was perceived as a "Forbidden City" by the white public in the past;

- psychomotor - to entice visitors to wander from one display unit to another, look at objects outside the stores and peep at artifacts through windows.

16 The goals of the exhibit were attained. The Fannin Foundation, and the Victoria Chinatown Lions Club financially supported the exhibit, and some Chinese resource persons assisted in artifact identification, storyline authenticity, Chinese calligraphy, and other tasks. The exhibit, covering an area of about 500 square feet, consists of four wooden structures that display the common structural and decorative components of Chinatown buildings, such as projecting or recessed balconies, "cheater storeys" (low-ceiling mezzanines), and horizontal and vertical signboards bearing Chinese characters.

17 There are six display units. The first unit is a hook showcase which marks the entrance to Chinatown. Inside the showcase, Chinese herbs and Western medicine are displayed, and the two systems of medicine compared. A large information panel on Chinatown and the occasional meowing of a cat draw visitors' attention to the Chinatown exhibit.

18 The second unit is Kwong Hing Lung & Co., a grocery store, in which salted eggs, preserved ginger, and other Chinese merchandise are kept. A tenement is on the second floor, where clothing is hung on a string. The third unit is Ka Lee, a shoe repairer's store. An advertisement on the store front reveals that the shoe repairer is also an employment agent.

19 Opposite Ka Lee is the fourth display unit, which is a recessed balcony of See Yup Tung Heung Hui (The Four Counties Association). Worship of ancestors and heaven takes place in the balcony, where a plate of fruit and an incense container are placed on a table.

20 The fifth unit is Man Yuck Tong, a herbalist shop in which drawers of herbs, a crusher, a grinder, cutters, and other equipment are displayed. A sewing machine, buttons and clothing occupy half of the ground floor because the herbalist is also a tailor. Boxes of herbs are stored in the "cheater floor." Herbs are prepared in the kitchen, where the brick stove, herb choppers, scales and other equipment can be seen through the window.

21 The last display unit is a dim alley, closed off by a wooden gate through which Chinese signs of two gambling clubs (Tai Lee and Tung Lok), a rooming apartment (Hop Wo Fong), and a restaurant (Kwong Chow Lou) can be seen. A peephole on the wall is used to screen patrons.

22 While passing through the exhibit, visitors can smell Chinese herbs and incense, and hear the faint clucking of chickens, and people chatting in different Chinese dialects. Next to the alley is L.G. Cook, a western druggist's store, which functions as a link between the Chinatown exhibit and the Old Town Gallery.

23 The tangible, visible, audible and olfactory manifestations of Chinese cultural imprints in British Columbia are very apparent in the Chinatown exhibit. Visitors to the exhibit will know more about the lifestyle and economy of the Chinese community, the difference between Chinese herbs and Western medicine, and the symbiosis between Chinese culture and Western environment. It is hoped that visitors will also tour Victoria's Chinatown, Canada's earliest Chinatown, and compare it with the Museum's Chinatown exhibit. They will then appreciate more the physical and cultural heritage of an old Chinatown, and recognize it as a unique, historic component of an urban fabric in Canada.