Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

Cooper-Hewitt National Museum of Design, New York, Mechanical Brides: Women and Machines from Home to Office

Curator: Ellen Lupton

Designers: Ellen Lupton (graphie design); Constantine Boyn, Laurene Leon (installation design)

Itinerary: Cooper-Hewitt National Museum of Design, New York, 17 August 1993 to 2 January 1994; Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles, 23 March 1994 to 27 May 1994

Publication: Catalogue, Mechanical Brides: Women and Machines from Home to Office, 65 pp., illus., Princeton Architectural Press, 1993. Paper U.S. $19.95, ISBN 1-878271-97-0

1 When Louise and Andrew Carnegie constructed their 64-room mansion on upper Fifth Avenue in New York in 1898, household technology was a nearly invisible, yet essential, aspect of domestic architecture. Their six-storey villa's sophisticated system of boilers, pipes, pumps, and machinery was relegated to the basement; kitchen and laundry were clearly separated from the main living quarters; and the team of 19 servants employed to manage the Carnegies' state-of-the-art equipment gained access to the family's lavish rooms only through a labyrinthine system of service stairs and corridors, designed especially to maintain the servants' invisibility.

2 It is somewhat ironic, therefore, that a major exhibition on household and office technology Cooper-Hewitt National Museum of Design, New York, Mechanical Brides: Women and Machines from Home to Office currently occupies five rooms of the former Carnegie mansion. Remodelled in the 1970s to accommodate the Cooper-Hewitt Museum (the Washington-based Smithsonian Institution's Museum of Design), the sombre interiors of the former home seem a curious backdrop for the 100 brightly coloured plastic and metal objects contained within Mechanical Brides: Women and Machines from Home to Office. The show's focus on women, too, is starkly juxtaposed against the quintessentially masculine, oakpanelled rooms, in which Carnegie no doubt hosted many of America's most powerful men earlier this century.

3 Mechanical Brides confronts head-on this male-centred, conservative world in which it is set. It also uses contemporary exhibition techniques in a subtle way to make instructive comparisons between the technology of Carnegie's era and that of the twentieth-century, middle-class home and office, the real subject of the exhibition. Perhaps the clearest example of this mechanical counterpoint is a large television and VCR, set boldly in a now-obsolete Carnegie fireplace. The hearth-cum-video is framed on each side by two shiny washing machines sitting on concrete bases (intended to suggest basement floors); the wall text accompanying the laundry equipment is printed on starched bed linen, suspended overhead from wooden dowels as if hung out to dry. Against the dark, deeply-sculpted panelling of the formerly aristocratic room, this scene is, to say the least, startling.

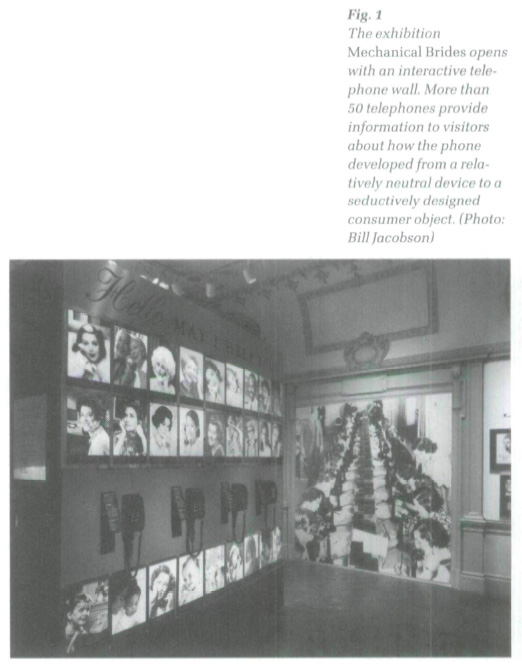

4 Mechanical Brides begins with an equally bold statement. A thick partition wall adorned with four wall-mounted, push-button telephones and 24 images of people on the telephone faces the entry to the exhibition sequence (Fig. 1). Intended to remind visitors of contemporary telephone booths and/or bus shelters by its bold graphics and use of back-lit images, this interactive wall invites visitors to use actual telephones to reconsider the place of telephones in modern culture. Surrounding images of historic telephones and media images of telephones suggest how this technology has acted as a link between the gendered spheres of home and work. Numerous jobs associated with women and centred on the use of the telephone in the twentieth century - secretary, receptionist, telephone operator - limited women's roles to passive receptors and communicators of information, rather than producers of information. Both the exhibition and the catalogue explain how women in these positions became human extensions of the technological systems they were expected to mediate.

5 The issue of gender and technology is brought into even sharper relief in the second room. In addition to the video in the fireplace (with an ordinary, three-seater couch in front), in which a variety of people discuss their personal views of laundry, and the display of eight vintage washing machines, this room also boasts three vitrines of historic irons. The walls are covered, like the first room, with advertisements and images from pop culture explaining the gender division of housework; race, class, and ethnicity in housekeeping as a business; and the concept of modernism in the home. Typical of the way the subject matter informs every level of the exhibition design, these images are matted in sheets of vinyl flooring and framed by sections of aluminum, typically used to finish the edge of kitchen counters.

6 This political approach to the subject of domestic technology is consistent with other projects by Ellen Lupton, the Cooper-Hewitt's first Curator of Contemporary Design, who devised Mechanical Brides. Lupton co-curated the controversial exhibition, The Bathroom, the Kitchen, and the Aesthetics of Waste, at the List Visual Arts Center, MIT, during the summer of 1992. Rather than focus on issues of gender, however, the MIT exhibition of mostly sinks, toilets, and toasters drew perceptive analogies between our cycles of economics, digestion, and plumbing.1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 17 The playfulness of domestic technology is celebrated in the third room of the exhibition, which features a collection of contemporary household machines inspired by the characters from The Wizard of Oz on a bright yellow display stand. Images on these walls also explore the romantic partnerships suggested by domestic technology; many of the advertisements aimed toward brides show explicit promises of marital happiness and even sexual satisfaction: a wedding ring is reflected in the shiny surface of a 1946 toaster; a woman paints a heart and arrow on her new dryer, surrounded by her smiling husband and children; another happy woman dances with her silicone-covered ironing board in an advertisement of 1956.

8 The weakest section of Mechanical Brides is the fourth space in the sequence, occupying the former conservatory of the Carnegie mansion and functioning as a hinge in the exhibition to turn visitors into the final room. Filled with plants and suggestive of an outdoor space, this greenhouse hosts a lawn mower and chain saw for the exhibition, suggestive of men's domestic technology. Lupton says the conservatory was intended as a very solemn place, where visitors could contemplate the laundry line bearing quotes about housework from a diversity of women. The display of objects, however, seems inconsistent with the other strongly thematic arrangements of material culture; given the general theme of the exhibition is the relationship of women and machines in the home and office, it seems incongruous (and smacks of tokenism) to include men and machines used outside the home. This section of the show is, in addition, a blatant reminder of the difficulties of designing exhibitions in a building conceived for a completely different purpose.

9 "Office Politics" is the focus of the final room in Mechanical Brides. The centrepiece here is a display of three secretarial work stations, each paired with an executive chair intended to simulate actual office environments. The furniture from the influential 1906 Larkin Building by Frank Lloyd Wright, for example, illustrates to visitors how the female clerks employed by this soap company occupied fixed chairs, while the male executives had chairs on wheels. Considered at the time as a modern, efficient office building, fixed seating was intended to increase the efficiency of clerks by limiting their mobility.

10 A built-in display case in this final room depicts the parallel relationship of typewriter design to women's subordinate positions in the world of work. Typing, like working on the telephone, was constructed as a kind of neutral communication of ideas generated by men.

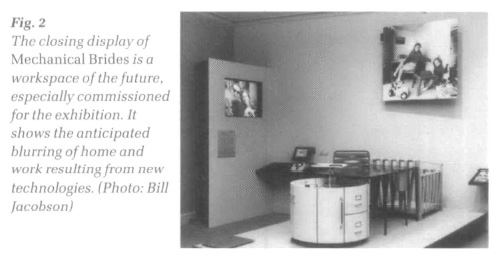

11 Two examples of contemporary design also underline the complexity of gender in today's "Office Politics." Next to the typewriters is a wearable computer, designed by a woman. This tiny machine, with both an eyepiece and an ear-piece, hangs like a necklace on the wearer's chest, delivering information directly to the retina. Next to the exit door of Mechanical Brides is a desk of the future (Fig. 2), commissioned by the museum for the exhibition. This conscientiously domestic prototype - it was intended to address the "live/work" space of the future -draws on the worlds of both home and work for ideas. The work station comprises a playpen and a combination of rotating filing cabinet and lazy susan, in addition to a horizontal work surface. Lupton says the piece was inspired by the powerful photo shown above the desk in the exhibition which appeared in the New York Times. It shows a frantic bank executive working at home in a chaotic setting with her infant, who is demanding attention and keeping her from her work.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 Mechanical Brides is a powerful exhibition about women and machines, a much neglected subject in academic scholarship. Its real contribution in terms of an approach to the field is that the show considers technology in a setting far wider than the home. Mechanical Brides, by illustrating with real objects the close relations between home and work, has added to our increasing suspicion of the so-called "separate spheres" theory, which defines the home as a relatively isolated institution in urban life. This notion, which formed the basis for pioneering work in women's history in the 1960s and 1970s, presumed the house as a place both antithetical to, and spatially separated from, the world of science, politics, and men.2

13 Mechanical Brides challenges this theory by drawing links between women/technology and office employment, architecture, and advertising, among other male-gendered domains. Lupton is interested, at every level of the exhibition, in how the public informs the private and vice versa. Drawing on the revolutionary work of Marshall McLuhan, she, too, appreciates industrial design as an aspect of mass media, rather than for its formal values, as is often the case in museums of design. The title of the exhibition is drawn from McLuhan's book of 1951, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man, in which he compared advertisements showing parts of women's bodies to the interchangeable parts of machines. Presumably this title pays homage to McLuhan's brilliant analysis of the social and political values of mass media, as well as his early interest in the relationship of sex and machinery.

14 In an exhibition so broadly based, it is no surprise that every type of technology displayed is not as deeply researched as in a smaller show. By including so many different types of technology spanning the entire century — telephones, laundry, cooking, typewriters, office furniture — the exhibition addresses the real impact of technology on women's lives at a relatively superficial level. At the same time, however, the great range of objects displayed — 95 per cent are loan objects — no doubt made the subject much more appealing to the non-specialist. In this respect, the 65-page catalogue will be more useful than the exhibition itself for purposes of further scholarship and teaching.

15 In the final analysis, it would be difficult to find a more appropriate place than the former Carnegie mansion for Mechanical Brides. The Carnegies were, after all, obsessed with technology. Theirs was the first private home in the United States to have a structural steel frame, was one of the first to boast a passenger elevator, and was extremely progressive in its use of central heating and air conditioning. The Carnegie mansion even included duplicates of every major piece of equipment, in case of failure. Although its systems were hidden in the walls, the house was, in every sense, a showcase for turn-of-the-century technology. Its reincarnation as the museum setting for Mechanical Brides has "exposed" once-invisible systems of technology, as well as the systems of power which have dictated the relationship of women and machines for most of this century. The servants' ghosts, at least, must be smiling.