Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

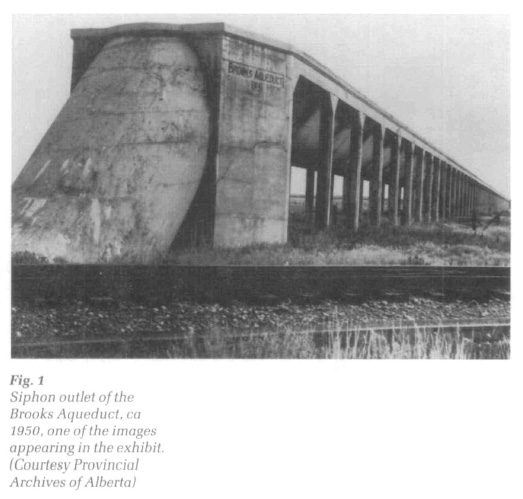

University of Winnipeg, Brooks: Coming Home

Curator: Sarah McKinnon, Art History Professor, University of Winnipeg

Author: Walter Hildebrandt

Artist and Designer: Peter Tittenberger

Duration: 12 January to 6 February 1993

1 The focus of this exhibit is the Brooks Aqueduct, one of many Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) irrigation projects - ditches, canals, dams, and aqueducts - that were intended to promote settlement in southeastern Alberta in the early part of this century. Construction of the aqueduct began in 1908, and three years later Brooks, 185 km east of Calgary, was incorporated as a town. The aqueduct was operational by 1914, but was beset with financial, construction and engineering problems which led to its takeover by the Eastern Irrigation District (EID) in 1935. The monumental project, an unprecedented feat of engineering and labour, was eventually abandoned after structural flaws rendered it inoperable.

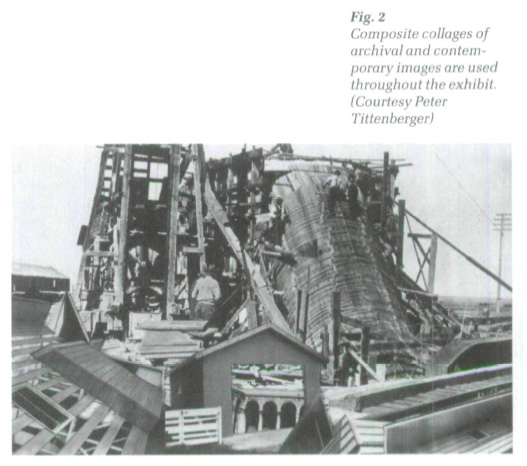

2 This story is told with a mixture of contextual narrative descriptions, quotations, anecdotal excerpts of oral history interviews, poetry, and graphics. Historical and contextual descriptions are laid out on 62 panels of text on sepia-toned paper. The text is derived from eyewitness accounts of the ruin, reflections of those who worked on the project, and Walter Hildebrandt's historical poems. In addition, there are 24 images. These are a combination of black-and-white archival photographs, and photographs altered with colour tints and plasticized overlays that provide a two-dimensional, collage effect. Generally, the story line is divided in half by a l m by 3 m colour computer-generated, pixel mural of the aqueduct. In the first section, visitors are given very general context about the history of irrigation in different parts of the world throughout human history. This is followed by a description of the construction of the aqueduct and its early years of development. The second part of the exhibit describes the unsuccessful efforts to make the project viable under the management of the CPR and EID, and its subsequent demise and abandonment.

3 Brooks: Coming Home, to its credit, is a rigorous intellectual exercise for those who are comfortable with descriptive, logically organized label copy. Many facts surrounding the aqueduct's history jump out at the reader unexpectedly, without the usual explanatory information that one finds in conventional displays. In one picture, for example, the overlay on an archival photograph shows a car driving on a highway (presumably to Calgary), while the text nearby reads:

a double take

cuz at first u can't

figure it out

it just looks like

a big grey mass of something

just when u look south

of the highway

goin' west towards Calgary

just sort of like a

tide that should be movin'

Other overlays contain contemporary objects like waterslides, or modern building materials. All the factual content and context is presented in similar fragmented fashion. It is also assumed that the reader has some prior knowledge of engineering and construction jargon. In order to understand what happened, visitors need to spend some time reading the text, putting together the material, rearranging and digesting it, and constructing the story.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 The fragmented text is a means of pursuing one of the major curatorial objectives: to "unsettle and even jar the viewer/reader to reconsider both form and content." There are risks in following this line. In order to deviate from conventional modes, curators may be forced to abandon traditional historical prerogatives, and unwittingly end up catering to popular entertainment rather than a popular presentation of history. Rather than present something that is both informative and interactive, the danger is that by offering something so different it is interpreted as a mere curiosity. Sometimes extremely novel presentations can lead the viewer to a-historical or even anti-historical directions. The visitor is invited to view the material as an engaged participant but ends up by consuming images and text without critical thought or reflection.

5 The other problem is that such presentations can react against traditional narrative styles, whose own unique power to evoke audience responses is ignored in the process. It is astonishing how many people marvel at the power of the spoken word of oral cultures, which transmit values and history to their descendants. The explosion of interest in oral history as a resource for education and as an interpretive tool for ordinary people in the last 20 years testifies to the power of narrative story telling. Perhaps the discomfort with the fragmented text persuaded one visitor to write "relevant, but obscure" after passing through the exhibit.

6 Unfortunately, there is no foolproof method of evaluating how an audience interacts with displays. The question is: how do popular audiences reconstruct these fragments into a meaningful journey into history without a store of factual and contextual information available to them? One panel contains references to wages for teamsters and labourers in 1919,1921, and 1922-25. Without some context, this can lead to the perpetuation of stereotypes of the "good old days," rather than inquiry into the complexity of situations that surrounded the struggle for wages and working conditions in that period. This is not a failure of the exhibit, but a comment on how difficult it is to question form and content in the presentation of history. It raises questions about what skills an audience needs to possess in order to participate in that ambitious curatorial objective.

7 One of the strengths of Brooks: Coming Home is that it invites the visitor to question the content of traditional modes of historical presentation. There are repeated references to authoritative and official histories of the Brooks site, where Hildebrandt draws attention to mainstream museum displays. One example is the Brooks and District Museum which has a bandstand donated by Nova Corporation:

there is a fine new

bandstand

where you might enjoy

your picnic lunch

and a five foot fence around the entire

museum

Traditional commemorative museum displays often reinforce nation-building progress narratives. Hildebrandt exposes these traditional forms for questioning. Commentary about these displays and narratives contained within them are implicitly critical, ironic statements about how history is constructed and presented to the public. The Brooks and District Museum, for instance, is commemorated as a 'walk through the ages,' with displays presenting

the Indian culture;

the ranchers;

the sheepmen;

the homesteaders;

the farmers;

the R.CM.P.

the C.P.R.: and

the E.I.D.

as well as articles from the war years.

8 Later, after reading about unsuccessful attempts to repair the aqueduct and descriptions about working conditions, there is the following statement about what the commemoration of the Brooks aqueduct site might mean to its contemporaries:

they went'n

declared it

an historic site

soon

the public will

get to go out there

we'll all

be told

how it once

worked

Visitors are not lectured about public programming, though the exhibit makes many subtle statements about the nature and purpose of public programs. Visitors are invited to ask critical questions about how historical memory is transmitted, and how authoritative interpretations of folklore are reinforced through popular appeals to the public imagination.

9 The unorthodox style of presentation reinforces the intention to construct a general, impressionistic, emotive history of the site. In Alberta, the aqueduct and its sister projects were justified by "boosterism, and agricultural 'progress'." Brooks shows how this experiment failed after monumental human effort, at the expense of the workers who built it and the farmers whose livelihood it was supposed to sustain. The poetry and narrative text effectively describe the emotions that the site evoked for workers, their families, and descendants. It is also used to scrutinize the motives and wisdom of large-scale, subsidized economic projects.

10 The CPR, we are told in one poem:

for buildin'

the railway

an' this here land

was preat'near useless

So in this part

of the country

They took a big shit kickin' first

tryin' make the land bountiful

But they got

smart

and eventually

got most of it back

by soakin'

the farmer

Notes in the visitors' book indicate that this populist tone was welcomed by the audience. "Working-class, made my day," wrote one observer. Unlike some populist narratives, however, Brooks correctly links these past projects to larger political and economic forces, and with the same progress-oriented dreams motivating present-day projects.

11 On the last panel, a long poem describes the legacy of the aqueduct as the offspring of "pirates and raiders — crazy with greed and fear" who:

move the last fresh reservoirs

of water

for the opulent artificial

California gardens

huge schemes

diversions

for ornamental deserts

Hollywood

feeding these colossal shallow false-fronted

man made

failures

And here this aqueduct

this skeleton of a dream

The exhibit successfully reconsiders "meta-narratives of progress that dominate nation-building narratives" by describing the negative impact that progress has had on human history and our natural environment.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 Brooks: Coming Home also encourages us to think in personal terms about our relationship with the past. The text often surfaces from Hildebrandt's own personal engagement with the past, as much as from his experience in writing technical-academic history for the Canadian Parks Service. His autobiographical reflections, observations and recollections reveal sensitivity to such issues as gender, race, and historical process:

my mother

with me in her

belly

washed floors

for ladies

in town

living on the edge

in a shack

ice two inches thick

grows on the walls

in winter

With poems like these Hildebrandt creates a poetic response to a material environment that is loaded with the potential for observation and interpretation.

13 I agree with the majority of visitors who thought that Brooks: Coming Home was an interesting and refreshing work, and I hope additional resources can be found to convert it to a travelling exhibit. If this happens there will be an opportunity to fix minor weaknesses.

14 The first of these is that the size of the text was too small (about Times Roman 12 pt), and because it was mounted approximately five feet above the floor, the copy could not be read by anyone unless they were standing very close. Other similar technical points, such as the quality of wall mounts, could also be addressed. Secondly, though the exhibit relies on the voices and recollections of observers, the identity of the observer is usually obscure. There are no footnotes and, with a few exceptions, the speakers are unidentified on the panels or the curatorial statements that were available. While it might be said that this is a way of challenging popular conceptions of authority and authenticity of official history (as expressed in footnotes), identifying the speakers would have enhanced the emotional and poetic responses to the site.

15 The prevailing economic climate is forcing all cultural institutions to work with smaller budgets and attract wider audiences to justify their cultural value, and, ultimately, their economic viability. Put crudely, public history is under severe pressures to pay its own way. In past decades, public history displays have been modified, revised, and re-presented to address the needs of contemporary audiences. The public has been offered many different opportunities to take part in the discovery, interpretation, and remaking of its heritage. Multimedia, gala events, and living history have helped to excite the public imagination, thus helping museums and other cultural institutions to appeal to wider audiences.

16 But at what point do innovative programming and entertainment reduce content to trivial curiosity? Will future programming help or hinder the communication of history to wider audiences? Can history be displayed in ways that are critical and entertaining, and still play a role for educating the public about the past in ways that are relevant to everyday life? Brooks: Coming Home shows that a thoughtful, relevant, and provocative inquiry into the meaning of an artifact in past and present society can be accomplished by experimenting with the form and content of presentation.

Curatorial Statement

17 The Brooks Aqueduct was begun in 1908 to bring water from the Lake Newell reservoir across a dried-up river bed two miles wide. The aqueduct was 60 feet high in places and brought water to an area of southwestern Alberta that was little more than a desert. It remained operational for 65 years.

18 Brooks: Coming Home combines visual and written languages assembled to begin a dialogue between past and present, form and content, as well as vernacular and more formal language. Both artists examine the visual and written narratives that dominate the historical record, not simply or even primarily to discredit the evidence, but instead to draw attention to what can happen when dominant narratives are "rubbed against the grain." Historical and photographic documentation is presented in a fragmented, tinted and altered form, then juxtaposed in unorthodox sequence to unsettle and even jar the reader/viewer to reconsider both form and content.

19 The Brooks Aqueduct was considered a major engineering feat in its day, but in the later decades of the twentieth century, mega-projects like the aqueduct have been questioned; critics no longer focus only on the positive results of these mega-projects but have analysed the consequences of these major alterations of nature. Enthusiasts for these large feats of engineering have been unable to foresee the ways in which their experiments would end in human, technological and environmental failure.

20 The meta-narratives of "progress" that dominate nation-building narratives are reconsidered here balanced off against the voices of those who constructed and lived in the communities around the aqueduct. Both artists are interested in considering a multiplicity of perspectives on what the aqueduct has meant for a wide variety of people - from those who went to the aqueduct to cool off in the trickle from the overflow, to present day historians who may never have seen the aqueduct when it was operational. Today, historians and artists are less likely to believe that history can actually be reconstructed 'the way it really was' and are more willing to be open about their sympathies. Indeed it is the poetic response of the artists here that helps keep the past alive and important to our culture — renewing it by reconsidering it. There may even be important political reasons for Canadians to keep alive a history that could well hold lessons for the future as countries begin to cast covetous eyes on the once-thought-to-be endless supply of water.