Abstract

In 1906, prominent Montreal architects Edward and William Sutherland Maxwell designed a new nurses' residence for the Royal Victoria Hospital. This paper offers an analysis of gender in a large, late nineteenth-century city hospital, the Royal Victoria, as well as an examination of the issues involved in designing a modern building type — the nurses' residence — in early twentieth-century Montreal. Precariously poised between private and public, the architecture of the nurses' residence clearly illuminates the equally controversial place of women professionals in Canada's evolving health-care system.

Résumé

En 1906, d'éminents architectes montréalais, Edward et William Sutherland Maxwell, ont conçu les plans d'une nouvelle résidence d'infirmières pour l'Hôpital Royal Victoria. Cet article fait l'analyse de l'effectif masculin et féminin dans un grand hôpital urbain de la fin du XIXe siècle, le Royal Victoria, de même que l'examen des questions inhérentes à la conception d'un édifice moderne de ce genre ߞ une résidence d'infirmières — au début du XXe siècle à Montréal. Se situant précairement à mi-chemin entre le public et le privé, l'architecture de la résidence des infirmières illustre également la place controversée des femmes de profession libérale dans le système évolutif des soins de santé au Canada.

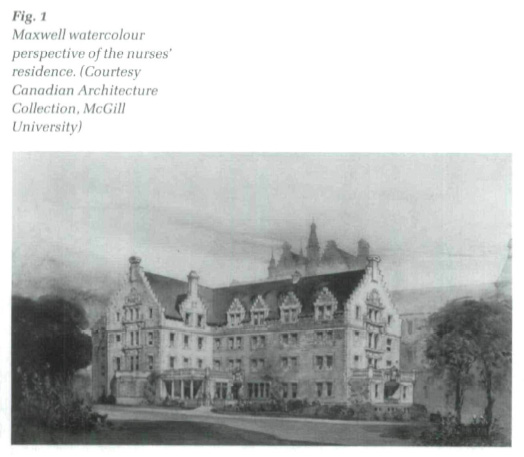

1 In May 1905 Professor Percy Nobbs of McGill University recommended the design of Edward and William Sutherland Maxwell as submitted in the limited competition held for the new nurses' residence at Royal Victoria Hospital (RVH) (Fig. 1).2 Certainly his choice of architect for the project came as no surprise. The Maxwell brothers had designed many of the gracious mansions which hugged Mount Royal to the west of the hospital, inhabited by the wealthy families who supported the hospital and attempted to direct its future.3

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 Other local architects, however, were commissioned to extend the building soon after its completion. In 1917, Hutchison and Wood, who had placed second in the 1905 competition, designed an addition to the north of the Maxwell building; the following year they added a kitchen.4 In 1931-32, the building was expanded once again. Lawson and Little's new wing to the west of the original nurses' home provided 132 additional rooms, as well as a gymnasium, reference library, dietetic laboratory, and lecture and demonstration rooms, for the expanding population of student nurses at the RVH.5

3 Rather than focus on the choice of architects by the hospital administration, however, this paper examines another side of the institution's architectural history, the complex relation between the architectures of the Royal Victoria Hospital and its expanding nurses' residence. Precariously poised between private and public, the building and its subsequent additions reveal the truly paradoxical relationship of domestic and institutional women's architecture in the early twentieth century. A real "room of one's own," at least for nurses, offered both autonomy and restraint at once.

4 The educational program for nurses based at the Royal Victoria Hospital did not begin with the realization of the Maxwells' new residence. Since the founding of the Training School in October 1894, nursing students at the RVH had lived amidst the large, open wards, exposed to the fetid air, contagious diseases, and never-ending duties of turn-of-the-century nursing.6 In earlier plans of the Royal Victoria Hospital, the women who worked day and night, trained countless others, and cared for the city's "sick and injured persons of all races and creeds, without distinction," had few rooms of their own.7

5 Unsigned plans of the hospital dated 1905 (which were in the possession of the Maxwells) may show some of these spaces in the original hospital intended for nurses but never built: a large dining room in the western section of the administration block (on Level F) and a single space intended for the head nurse in the east tower (Level E).8 The original drawings for the hospital, however, which also do not necessarily reflect what was constructed, show a series of small rooms and a waiting room for nurses in the central administration building, in addition to a tiny space "with inspecting windows, which command the entire wards."9 There was also a special office on the principal floor in this early scheme assigned to the Lady Superintendent.10 There is little evidence however, at this point, to ascertain where the first nurses at the RVH may have slept.11

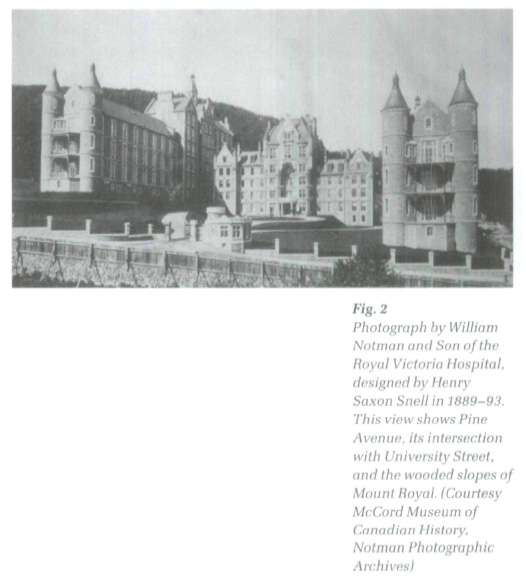

6 The main building of the RVH was designed by British architect Henry Saxon Snell in 1889-93, who was well-known in England and Scotland as the designer of workhouses and hospitals, and as the author of two significant books, Charitable and Parochial Establishments (1881) and Hospital Construction and Management (1883). A central administration block and two long and narrow open wards form a U- shaped ensemble facing south, towards McGill University, with which the hospital is affiliated (Fig. 2). Influenced by the ideas of Florence Nightingale, Snell's building was a "pavilion hospital," in which the separation and isolation of both patients and diseases were thought to discourage the spread of infection.12 Constructed of Montreal limestone, the hospital was also distinguished by romantic turrets framing generous sun porches at the corners of its imposing medical and surgical wards. Snell modelled the Montreal hospital on Edinburgh's Royal Infirmary, constructed by David Bryce in 1870. This "Scottish baronial style" pleased the hospital's upper-class patrons, whose families had emigrated from Scotland.13

Display large image of Figure 2

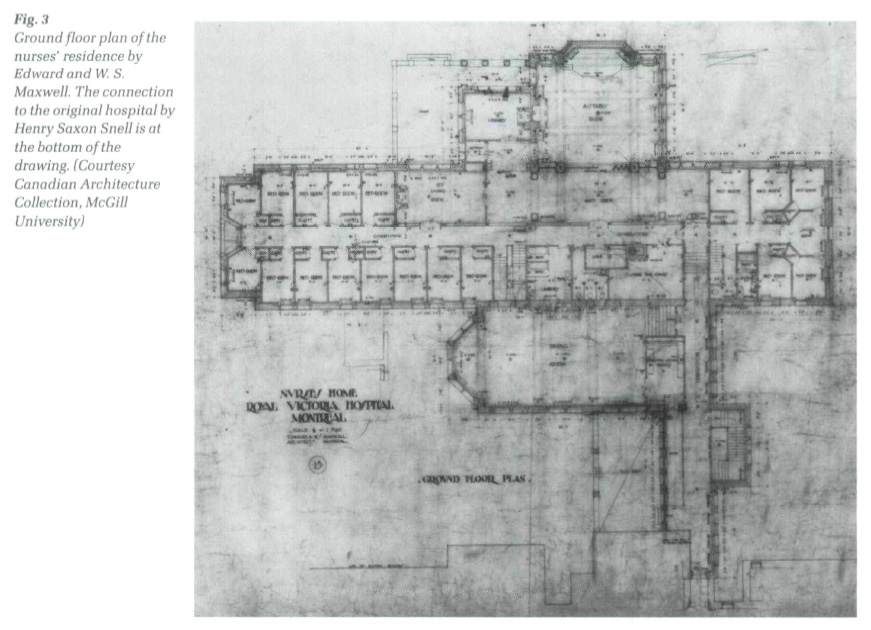

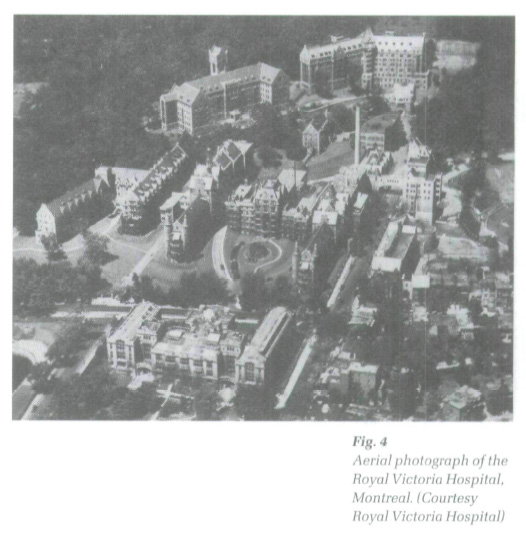

Display large image of Figure 27 The construction of the new residence was intended to improve the daily lives of the nurses at the busy urban hospital. Separate quarters were considered particularly imperative after a fire in 1905 damaged many of the nurses' bedrooms on the fourth floor of the Snell building, forcing them to sleep in the surgical wing for several months.14 Adjoining the ventilation tower of Snell's west or surgical wing on the slopes of Mount Royal, the Maxwells' five-storey, fireproof residence gave the nurses private space within their sphere of work, and status and visibility in the community (Figs. 3 and 4). In its heavy masonry construction, stepped gables, and details intended to evoke a particularly Scottish medical tradition, the new building mimicked, to some extent, its older neighbour, to which it was directly connected through a passageway above the east entrance.

8 The RVH nurses' home also drew heavily on middle-class domestic architecture, offering its aspiring residents 114 bedrooms, ten sitting rooms in which to socialize in small groups, a grand dining room, and a sequence of elegant spaces on its west side, including a library, living room, anteroom, and a large assembly hall with a stage. These spaces were deliberately home-like, intended to reflect the residential function of the new building and were given special emphasis in the massing and elevations of the building. The nurses' home as a building type, at this early stage of its development, knew nothing of the more institutional classrooms and demonstration labs characteristic of later nurses' homes.15 The education of nurses at this time was largely conducted in the hospital itself.16

9 Even the siting of the building was romantic. Nestled among the trees and poised on the steep ground west of the Snell building, the original nurses' residence was only partially visible from Pine Avenue, the busy thoroughfare in front of the RVH. The winding pathways and obliquely-placed gateways of the growing hospital complex ensured that the residence was mostly seen in perspective views.

Display large image of Figure 3

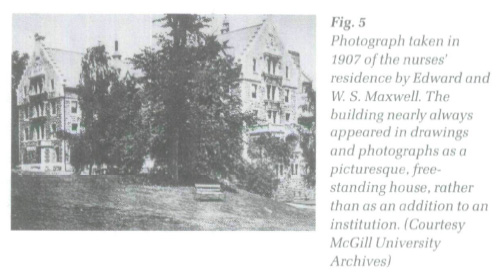

Display large image of Figure 310 The agitated silhouette of the home's stepped gables, which were presumably inspired by Snell's extensive use of the Scottish feature on the hospital wards, ventilation towers, and administration block of the earlier building, added to the romantic perception of the building. So did the fact that the Maxwells' nurses' residence was the first major extension to the hospital to break the apparent symmetry of Snell's monumental courtyard.17 This gesture expressed the newer building's non-institutional nature, which was further differentiated by the proliferation of dormers and stone railings on the Maxwell building. Indeed, the Maxwells' perspective view (Fig. 1) emphasizes their building's isolation from the Snell hospital, whose west tower and ward loom behind the new building in the drawing. The vantage point selected for the drawing and for many photographs (Fig. 5) of the building completely obscured the residence's connection to the hospital, making it appear, instead, as a free-standing, isolated (and therefore smaller), domestic structure.

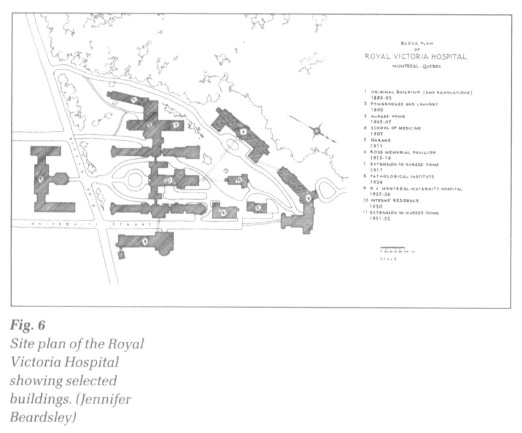

11 This idea of a separate, seemingly domestic structure situated in a romantic landscape was essential to the experience of the first nurses' residence. In addition to the winding flagstone path, which, as one resident of 1933 described, "entices us to follow whither it doth lead; we yield and follow it to the door of the Home,"18 the location of the nurses' residence to the west of the hospital ensured that it was seen against the backdrop of Mount Royal's wooded slopes (Fig. 6). The area above the original hospital was vacant at this time; Percy Nobbs' own Pathological Institute was constructed to the east in 1924, across University Street from the Snell building. As was the case with many late nineteenth-century institutions for women, particularly colleges, it is likely that the western site was considered more appropriate for the nurses' residence because of its more natural, "untouched" character.

12 This association of women and wilderness was central to the process of suburbanization in the nineteenth century, as well as in the location of the first colleges for women at universities, which were typically relegated to the periphery of the campuses or even cities. It stemmed from long-established conceptions of nature, understood in the late nineteenth century as healthier, safer, and more beautiful than the unpredictable, industrialized city.19 In the cases of both suburbs and early colleges, this widespread belief that women required protection from the dangers of urban life meant that they were removed or separated from centres of power, which tended to be located in more urban (less natural) locations.20

13 The eastern section of the large RVH site (both sides of University Street) has been perceived for a century as a more masculine, technology-oriented (urban) area. In addition to several prestigious medical buildings, it housed the power house/laundry building (1900) and ambulance garages (1911), while the western and northern edge of the roughly triangular site - the steep, rocky, wooded mountainside - was reserved for women (and wealthier patients).21 This edge still today is marked by the Allan Memorial (a renovated mansion), the former nurses' residence, the Ross Pavilion (1915-16), and the maternity hospital (1925-26).22 Just beyond lie the heavily wooded, rocky slopes of Mount Royal.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 414 Despite the separateness of the building as expressed in the drawing and photographs, the actual connection of the nurses' residence to the hospital building proper was a blatant statement of the institution's expectation of total commitment on the part of its student nurses. The narrow passage, carefully detailed by the architects, expressed - maybe even ensured -the fact that the nurses' six-and-a-half-day work week left little time for any life outside the hospital.23 The actual intersection of the hospital and nurses' residence was given elaborate architectural attention; the Maxwells' designed a special door for the juncture.24 Its decorative ironwork must have warned unwelcome visitors of the more private, domestic quarters beyond.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 515 This close connection between hospital and nurses' residence was uncharacteristic of buildings constructed later in the century. Indeed, the influential Survey of Nursing Education in Canada, conducted by George Weir in 1932, recommended that nurses' residences be separated from hospitals, allowing "adequate opportunity for privacy, rest, quiet retirement for study and for cultural recreation."25 By then the modernization of both the hospital and the profession of nursing (and women in general) meant that nurses could demand a certain degree of autonomy from the hospital. This autonomy was expressed in spatial terms by the physical distance separating their places of residence and work. Edward Stevens, an expert on hospital architecture and designer of two major buildings at the RVH, described the separation of residence and hospital in the 1920s as beneficial to the patients, taking the nurses' need for recreation for granted.

Stevens also emphasized the need for nurses to "go out of the environment of the sick room, out of the sound of suffering, out of hospital smells, and in fact out of the hospital atmosphere."27 In this earlier period of development, however, the need for nurses to escape their workplace was unacknowledged in spatial terms.

Display large image of Figure 6

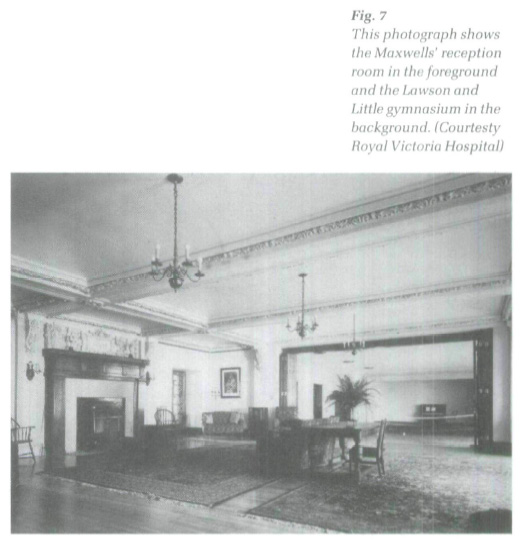

Display large image of Figure 616 The building's interiors, too, were quite domestic in terms of their physical form, as well as their intended use. Photographs of the new wing added by Lawson and Little show the social spaces typically provided for nurses throughout the century. The new reference library, for example, replaced the earlier library by the Maxwells which was subsumed in the new wing's entrance, while a new gymnasium extended from the Maxwells' original reception room (Fig. 7).28 These rooms were furnished with comfortable chairs and tables, typical of middle-class houses at the time. The furniture was arranged casually, loosely grouped around fireplaces and pianos, probably intended to simulate intimate, home-like gatherings.

17 The yearbook praises the domestic character of the new residence, remarking on the foyer's "soft lights," which, the author suggested, "invite us to linger." The reception room on the first floor, "tastefully and comfortably furnished," was the setting for bridge parties and teas. The library, shown here, also illustrated in the yearbook, was "luxuriously furnished with piano, chesterfields and occasional chairs."29

18 Martha Vicinus has pointed out how many early buildings for women — colleges, schools, settlement houses — looked like large houses. This domestic imagery was probably intended to smooth the transition for middle-class women to the world of paid work, while at the same time offering the promise of gentle protection in that realm. "The surroundings," says Vicinus of the first colleges for women in England, "bespoke permanence, seriousness of purpose, and the same solidity that marked the middle-class families from which the bulk of them came."30 The house-like appearance of the RVH nurses' residence probably assured anxious parents, too, that their daughters would be looked after, protected, and separated from the hospital, the street, and the city beyond.

19 The class-conscious profession of nursing may also have presumed that the association of the residence with upper-middle-class houses would attract young women from wealthier families. Just as the nurses' uniforms made young graduates feel "dignified and poised," the new building may have been intended to impose middle-class values on working-class women, whose backgrounds were increasingly unacceptable to the profession in the decades following Nightingale's sweeping reforms.31 Edward Stevens pointed to the domestic character of the architecture, expressing concerns over both class and performance:

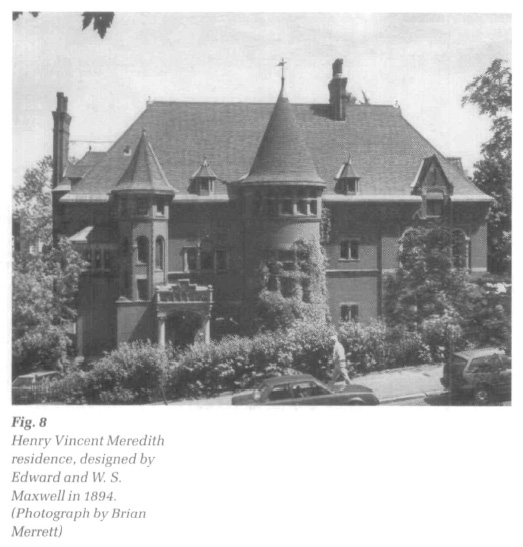

20 From this perspective, Nobbs had chosen the ideal architects; the Maxwells were masters of domestic design. Indeed, mansions designed by the brothers in the surrounding neighbourhood for prominent officers and benefactors of the hospital featured many of the same characteristics as the nurses' residence. Henry Vincent Meredith was president of the RVH from 1913 to 1929. His family's home, built in 1894, was probably the closest Maxwell house in terms of physical proximity to the hospital. It comprised elegant public rooms, expressed on the building's exterior, with private family spaces (Fig. 8).33 Like the nurses' residence, it boasted fine wood panelling and gracious circulation sequences; like all upper-middle-class residences of its time, it saw the strict separation of family and servants, men and women, adults and children. Its rooms were highly specialized and elaborately decorated. It is an ironic twist of fate that this house (and several others designed by the Maxwells) became part of the institution when bequeathed to the hospital later in the century.34

21 Although there were no special apartment buildings for working women constructed in Montreal, as there were in both New York and London, the city had a well-established landscape of residences for women.35 Montreal's many convents constitute an interesting example of extremely sophisticated (and large) residential blocks, which were often combined with enormous hospitals.36 Like the RVH, the convents were typically H- or U- shaped ensembles of narrow greystone buildings. The Montreal convent was usually four or five storeys, capped by steep gable or hipped roofs with dormer windows. Convent elevations featured repetitive rows of uniform windows, with little indication of the variety of overlapping spaces within the building.

22 A closer neighbour to the Royal Victoria Hospital was the Royal Victoria College (RVC). The first residential college for women at McGill University, it was founded in 1896.37 The original RVC, designed by the well-known American architect Bruce Price, was completed in 1899.38 It comprised classrooms and a huge dining room on the ground floor, while the assembly hall, library, parlour, and more classrooms were on the first storey. The upper two floors of RVC had variously shaped bedrooms and shared sitting rooms, arranged along a straight corridor. The hospital and the residential college shared more than a concern for women; both were established through bequests by wealthy benefactor Donald A. Smith, or Lord Strathcona. It was he who approved the idea of a separate building as a home for nurses at the Royal Victoria Hospital.39

23 In spite of the traditional, domestic attributes of the nurses' residence, the building type became a trademark feature of the "modern" hospital throughout urban North America. An implicit assumption in the development of the type was that the more efficient the nurses' residence, the more efficient the hospital in general. This led to the gradual inclusion of educational spaces within the program of the nurses' home, a mark of both decreasing reliance on the hospital per se as the primary site of nursing education and of increased specialization within the nursing profession. "Modern" nurses' residences built after the 1920s included social spaces that tended to be multifunctional, accommodating complex changes in use, relative to the earlier near-replicas of traditional domestic spaces. An example of this is the transformation of the Maxwells' assembly room of 1905 into the expanded assembly room/gymnasium space of Lawson and Little in the 1930s. "It is a convertible room appearing now as a ballroom, now a gymnasium and again as a lecture theatre, seating comfortably two hundred and fifty persons," boasted the 1933 yearbook. Despite this "modern,'' multifunctional conception of the room, social rooms in nurses' residences were typically furnished in an extremely conservative manner. The rooms at the RVH, for example, featured oriental rugs, upholstered armchairs and couches, Windsor chairs, and heavy draperies with sheers.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 824 The basement level, reflecting the full integration of educational spaces into nurses' residences by this time, housed the classrooms and labs.40 Although this "teaching unit" occupied an entire floor, these rooms received no special treatment in the massing or elevations of the extension. In terms of planning, however, the educational rooms were considered extremely up-to-date, planned as they were on "scientific" principles. The classroom, for example, had a sloping floor, allowing each student to view the blackboard in the front of the room; the demonstration room included beds, model trays, and mannequins, simulating the real hospital environment next door.41

25 At the same time as the building saw the introduction of these supposedly modern features, the nurses' residence was still an arena in which the private lives of nursing professionals could be closely supervised and controlled by the hospital administration. Student nurses could not marry; they kept strict curfews and their friendships were carefully monitored.42 In the 1920s, nurses were required to wear hats when leaving the building and to return home by 10:00 p.m. Smoking, dating the so-called "housemen" (residents), or mentioning the issue of salary were strictly prohibited.43

26 Lawson and Little's monumental extension to the Maxwells' building in the early 1930s gave physical form to many of the restrictions imposed on nurses' lives. The new building continued the general massing of the earlier residence by extending the west end of the Maxwell project with a new entry sequence (through the former Maxwell library). This hallway led to the generous gymnasium behind the former stage of the Maxwell assembly room. A medieval-revival tower housed the elevator, another modern feature.

27 The tower also marked the crossing of this long hallway and the double-loaded corridor that commanded the more residential section of the new extension. Like the educational rooms in the basement, bedrooms in the new wing were considered extremely up-to-date, "artistically furnished in a green, rose or tangerine colour scheme."44 Special bedroom furniture, like the multifunctional social spaces in the new wing, served several purposes at once. A single piece served as dresser, desk, and bookcase, for example.45 The section of the building running from the elevator lobby in the tower, southwards, toward Pine Avenue, was known as "peacock alley," because of its bright colours and highly decorated appearance.46

28 The expansion of the residence so soon after its completion may have sprung from the hospital's desire to segregate nurses even more than the original home prescribed. Of great concern to the hospital administration, after all, was the fact that, even after the construction of the original residence, student nurses continued to have close contact with the male staff. In the early 1920s, for example, when the Maxwell building no longer accommodated the number of nurses working at the RVH, students whose names began with the letters A through ) had been housed in part of the former Ward K, which had been converted into a temporary residence. The other half of the former ward was occupied by the "housemen" (residents), separated from the student nurses by only a particle-board partition. "In no time a direct communication system had been established," recounted Eileen Flanagan 50 years later, "by means of a clothesline stretched across the alleyway between the two wings. Many a note and batches of homemade candy were passed across."47

29 This notion of the necessary spatial confinement of nurses, no doubt stemming from their youthful, unmarried state and selfless commitment to helping others, was expressed in the Canadian architectural press throughout the twentieth century. Advertisements for building products in the Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, for example, into the 1960s, frequently featured nurses with architectural components which emphasized hygiene, safety, and quiet (Fig. 9).48 Nurses shown with locks and doors emphasized their roles as "guardians" of the all-important threshold. This pointed juxtaposition with doors and door hardware may also have been an explicit reference to nurses' purity and chastity; the thresholds depicted in the press, in this way, implied the containment of women in spaces controlled by men.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 930 Nurses' alleged endorsement of "quiet" materials, such as acoustic ceilings and flooring, may have reflected their supposedly passive qualities.49 Nurses at the RVH were constantly threatened with expulsion and "never made to feel that we were in any way indispensable to the illustrious establishment." "Well, it will only take a car ticket to take you home," claimed Lady Superintendent of Nurses Mabel Hersey to new student Eileen Flanagan in 1920. A teacher and member of the first graduating class, Nellie Goodhue, apparently repeatedly told her probationers: "If any of you wishes to leave, it will cause no more effect than dipping a finger in a pail of water and pulling it out."50

31 This confinement and surveillance of student nurses in early twentieth-century hospitals was primarily the responsibility of the head nurse, or Lady Superintendent. Lawson and Little's plans of the early 1930s reflect the important place occupied by Miss Mabel Hersey, who was superintendent from 1908 to 1938 and figured centrally in the development of nursing education and the profession in Quebec.51 While the inclusion of the classrooms, library, and gymnasium must have appeared as fairly progressive at the time — the institution's maintenance of the students' minds and bodies — the subtle renovations made to the Maxwell building by the later architects are extremely telling. Four bedrooms in the south end of the original building were transformed at the time of the new addition into a relatively luxurious four-room apartment for Hersey. Critical to its function in the growing complex, of course, was the new suite's strategic position overlooking the entrance area and stairs. Inside the building, Miss Hersey could easily survey the long corridor of the residence's main floor.

32 This form of direct surveillance was unknown in other residential sections of the hospital complex and may not have even occurred in the earlier nurses' residence of 1905, as the Medical Board had suggested that the Lady Superintendent's quarters should remain in the Administration Building, even after the construction of a separate Nurses' Home,52 The (male) Superintendent of the entire hospital, for example, did not even live at the hospital, underlining again this important question of which employees were permitted to live apart from their place of work.

33 Medical interns, who did live at the hospital, moved freely throughout the institution and were seen as fundamental members of the hospital establishment. In 1930, the RVH constructed a special residence for interns, designed by Ross and Macdonald, on the foundations of Ward S, the old isolation pavilion and original hospital laundry building. The new four-storey, fireproof home for 40 interns was located directly behind Snell's administration block, in a (commanding position at the centre of the entire complex, between the historic building and the new, more "scientific" hospitals designed by Stevens and Lee, which had been constructed up the hill.53 Like the nurses' residence, the interns' building was a long, narrow building with stepped gables at its ends (Fig. 10). Social spaces provided for the interns, however, were intended to encourage qualities associated with masculinity and power; the first floor billiards room was featured prominently in photographs of the hospital's resident interns.54 Promotional photographs showing a typical day in the life of an intern featured him in active modes, often controlling new technology or performing medical procedures; nurses, on the other hand, were featured in the hospital's promotional material gathered around a piano, engaging in informal conversations, or watching television. Even in the enormous complex of the modern hospital, doctors-in-training were seen as men of science, while: student nurses were pictured as women at home. The planning of the hospital, as we have seen, is material evidence of these gender roles.

34 Historian Judi Coburn has noted how nursing has been shaped by two powerful ideological forces: the "bourgeois ideology of femininity," which attempted to "contain women's work outside the home within the duties of homemaking," as well as the allure of professional status.55 The architecture of the RVH nurses' residence reflects this duality of forces that shaped the profession. While the building's homelike character was intended to attract middle-class women to join the ranks of the growing profession, these same architectural features also served to limit women's participation in the world of health care.

35 But the buildings also served very positive roles in the shaping of the Canadian nursing profession. Residences gave nurses real space in which to live and work, in contrast to their prior "invisible" occupation of the hospital in general; the residences' clear connection to the hospital — in terms of both a real physical link and stylistic congruity — acknowledged the students' gruelling schedules and total commitment to nursing. Most significantly, the architecture of nurses' residences offered single women a place to live in the city, outside the traditional, middle-class (or working-class) home.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1036 In addition, the history of this much-neglected building type should remind us, as architectural historians, of the pitfalls of isolated typological studies. The dynamic interplay between the architectures of the hospital and the homes of the surrounding neighbourhood is material evidence of the murky distinctions between domestic and institutional architecture at this time. The study of architecture designed for women underlines this danger, as it nearly always represents a carefully negotiated compromise of private and public space.

37 Today, the section of the Royal Victoria Hospital that once housed its student nurses is generally indistinguishable from the rest of the institution. Its finely crafted interiors have given way to the more anonymous, undecorated, "scientific" design of postwar hospital architecture. The only traces of its tenure as purpose-built architecture for women are in extant architectural drawings and photographs, preserved largely because the original building and its additions were designed by relatively well-known (male) architects. The mere footprint of the nurses' residences in the ensemble, nonetheless, is a potent reminder of both the presence and absence of women in the twentieth-century city.