Exhibit Reviews / Comptes rendus d'expositions

The Art Gallery of Ontario, The Earthly Paradise: Arts and Crafts by William Morris and His Circle from Canadian Collections

1 William Morris is consistently seen as the most significant of nineteenth-century designers because of his influence on subsequent generations. The chief reason for his stature has been his identification and eloquent discussion of issues that are still central for designers, including the role of the professional designer in industry and in society, and the relationship between function, materials and aesthetics. Morris's life (1834-1896) coincided with the transformation of a traditional, agricultural society by Victorian capitalism, and the contradictions in his thought and work reflect the confused responses of his age to this chaotic process of industrialization. Morris cannot be (principally by William De Morgan) is full of the technical and stylistic inventiveness and love of grotesque for which De Morgan is known, but seems like an interruption in the sequential presentation of Morris's own creative development. The superb quality of the best of Morris's design output really shines in the next, and largest, display area, which shows a selection of wallpapers and textiles by Morris and his followers. Morris produced hundreds of designs for fabrics and wallpapers, many of which are still in production. Their great and enduring popularity is a tribute to the humanity at the core of his design philosophy, as much as to his visual abilities. His views on pattern design were firmly entrenched in his love of nature. As Morris explained in lectures such as The Lesser Arts of Life, if "the keen delight which we ourselves have felt" is not communicated, then we should "choose honest whitewash instead." However intricate his patterns became, the designs always retained the integrity of the surface plane, though for Morris, design was never a purely formalist exercise. Meaningful patterns contain not only geometric order, but also richness and "mystery." The other source of the growth of his design — a laboriously acquired knowledge of techniques and processes — is particularly well demonstrated by a matchpiece (a role of wallpaper showing the progression of the colour printing sequence) and an accompanying video. On repeated visits, it was obvious that this fascinated an enthusiastic public.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 22 Morris designed wallpapers from 1862. These and his textile designs became a mainstay of the second version of his company, Morris and Co., founded after the dissolution of the original partnership in 1874. The business Morris established so successfully was centred on an earthly, domestic paradise rather than the Christian one. The commercial context for the firm's activities is reinforced as visitors pass through a replica of the shop front of Morris and Co. on Oxford street at the turn of the century. This device also helps to alleviate the (perhaps inevitable) treatment of expensive household furnishings as fine art when displayed in museums. Showing items in a window-display setting reminds us that this is design — adding value for profit. As Morris's socialist convictions grew, he anguished over the resulting contradictions, though this point is not, and perhaps could not be, forcibly made through the exhibition medium.

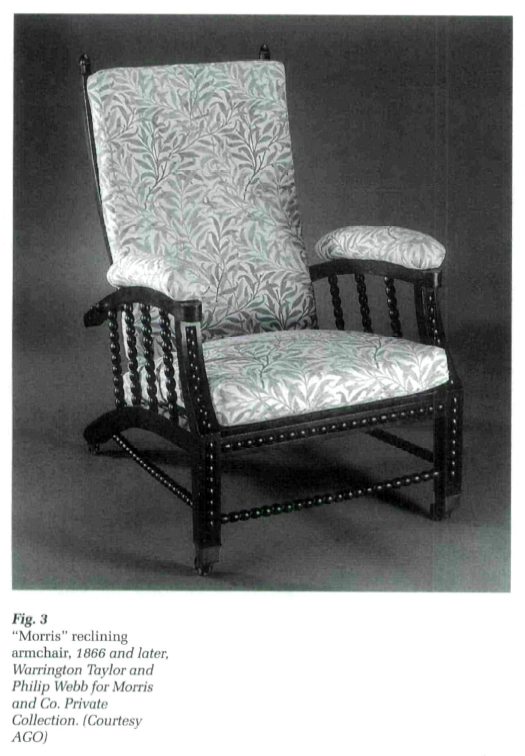

3 The show continues to provide a context for the firm's products by maintaining the domestic theme in two rooms. Here, the design demonstrates successfully Morris's approach to interiors of different scales. The first, small room, appropriately wallpapered, contains photographs of Morris and his friends, particularly Burne-Jones and family, their homes and studios (Fig. 2). The theme continues in a large, dark-green "drawing room" showing carpets, tapestries, embroideries, furniture and fabrics (Fig. 3). Once again, colour, space and lighting are effectively employed, recalling the dining room that Morris, Webb and colleagues designed for the South Kensington Museum (now Victoria and Albert) in 1867. Aesthetically, Morris's career emerges as an evolutionary rather than a revolutionary development from gloomy Victorian historicism.

Display large image of Figure 3

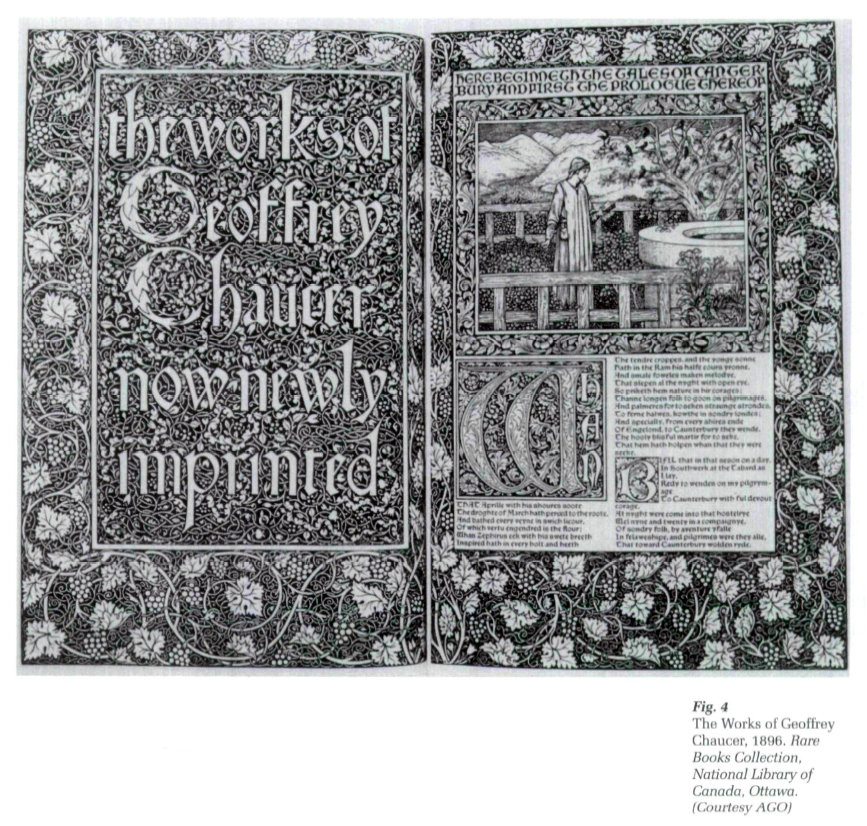

Display large image of Figure 34 The final section of the exhibition deals with one of the most important and influential aspects of the design activities of William Morris, the work of the Kelmscott Press, which he founded in 1891. Always a bibliophile and admirer of medieval illumination, Morris loved the completeness and self-contained nature of beautiful books while he deplored the standard of Victorian book design. With characteristic thoroughness, he studied inks, papers and printing processes and designed his own typefaces, decorative borders and bindings (Fig. 4). The Kelmscott books are Morris's most integrated statement, combining design and craft with literature while reflecting his historical and social concerns. In the AGO exhibition, his most famous, richly adorned titles are shown together with early printed books which he owned and which influenced his approach. The resulting comparisons are extremely valuable because here, as elsewhere, Morris proceeded from a profound appreciation of historical models, notably the fifteenth-century Venetian printers (his strong views on every aspect of book design are expressed in his essay, The Ideal Book). Morris carefully adapted typefaces to increase legibility and attempted to harmonize the relationship between Roman capitals and Gothic lower-case forms. His layouts were also based on intimate study, but highly systematized as Morris sought an "architectural arrangement." Decorations by Morris, and illustrations by Burne-Jones and others, similarly demonstrate a very personal synthesis of style while conforming to this carefully structured and modern approach. The only quality that detracts from his achievement (to a late twentieth-century sensibility) is the occasional, suffocating luxuriance of medieval fantasy.

5 Morris is problematic as the subject for an exhibition. In addition to his sheer productivity, he was prominent in ways that are difficult to exhibit — as a poet, essayist and political activist — and his many roles are impossible to divorce from one another. The chronological, decorative arts approach adopted by the AGO, though presumably effective in presenting his visual output in a coherent manner to a broad audience, is therefore only one of many possible formats for such an exhibition. As Pevsner has remarked, in Pioneers of Modern Design, Morris's views lift design concerns "from aesthetics into the wider field of social science." Consequently, Morris's primary importance lies in his principles and in his influence on practice rather than on style. This is clearly shown by his seminal role (too extensive to outline here) for the craft communes and private presses, founded in Europe and North America at the end of the nineteenth century, and for the idealistic Modernist design schools of the early twentieth century. To communicate something of the full significance of Morris from the design history point of view is, therefore, difficult in an exhibition. Some visual references to contemporaries outside his circle, to the Arts and Crafts movement in North America (particularly in graphic design) and to the following generation in Europe, would have been a valuable conclusion to the exhibition and would have enriched the extremely informative catalogue, but both may have become too large and may have lost the focus on Canadian collections. On balance, stressing the visual and experiential value of the exhibition as a medium of communication is the correct choice. The show is a major achievement and it will be interesting to compare it with the one being planned by the Victoria and Albert Museum, to mark the centenary of Morris's death, in 1996.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4Curatorial Statement

6 When we first began working on this exhibition it was very object oriented. Fabulous things kept coming out of Canadian closets, and naturally our excitement centred on the physical beauty of the works themselves. But it was in conceiving the exhibition layout that we realized that the exhibition was not ultimately about things at all, it was about ideals: It was about Morris's vision and its physical and intellectual dissemination, and about Morris's great dream for humanity. This transcends all the objects and still speaks directly to us today. The great green "drawing room," which we thought began as a figment of our imagination, which we laid out according to Morris's design principles, could have looked like a glorious jumble. Instead, it is the most convincingly real Morris and Co. interior I have ever seen. I realized that Morris had thought through all the permutations and combinations of the objects he created and had masterminded even our installation! The genius of Morris took over, and the result has been deeply moving. Morris basically beat us to it!