Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Philomène's Peacock

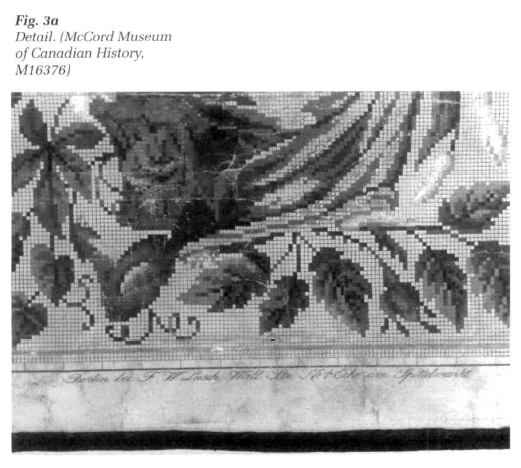

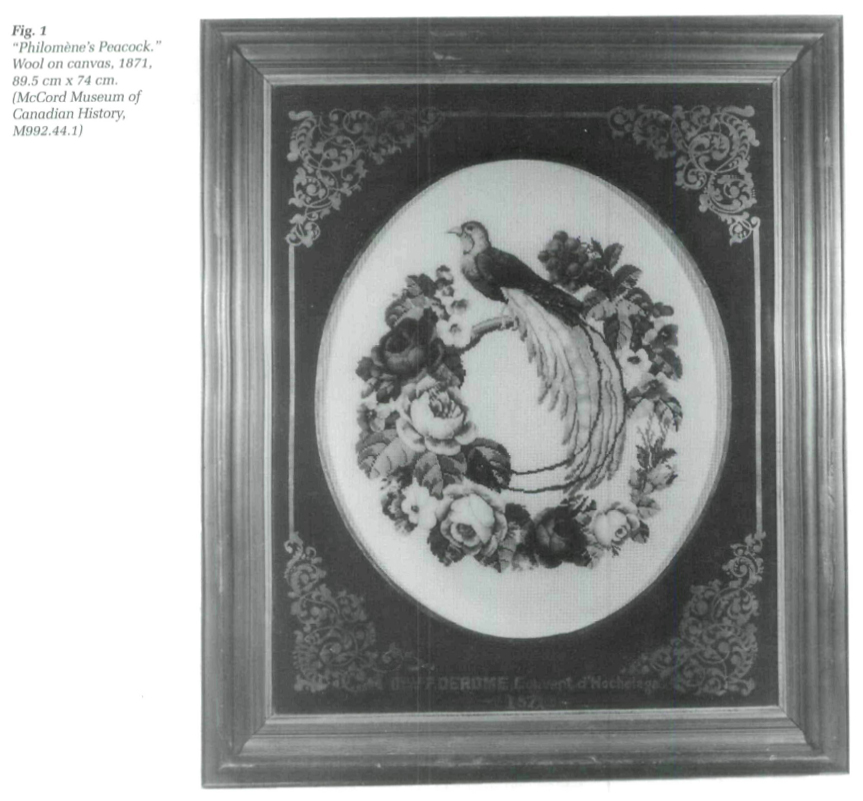

1 In December 1991, a splendid Berlin work picture1 was donated to the McCord Museum of Canadian History. This work, depicting an exotic bird encircled by a wreath of full-blown roses, is an outstanding example of nineteenth-century Berlin work embroidery. What makes this work more interesting is that within the frame there is inscribed the name of the needlewoman, the convent at which she studied and the year in which the work was completed (Fig. 1). Even a brief study of this work encouraged further investigation of both its provenance and the tradition of Berlin work, particularly in Canada. Much has been published about ecclesiastical embroidery of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,2 but little, if anything has been written about other types of decorative needlework in Canada. While general background information on Berlin work is found in many English and American publications, references to this type of needlework in Canadian publications are harder to find.3

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 In the late twentieth century we tend to forget that until the early 1860s, when the sewing machine had become a familiar household tool, all apparel and all household textiles were sewn and ornamented by hand. Proficiency with a needle was more than a casual accomplishment; it was a necessary skill. The following words from a history of needlework published in 1842 underline this fact:

3 Decorative needlework has been used to ornament objects and apparel throughout recorded time (embroidered objects have been found in Egyptian tombs): materials have varied, designs have changed and stitches have evolved from the simplest possible to the extremely complex. While the finest embroidery, expensive because of the skill and time required for its creation, was limited to people of means, embroidery also ornamented many objects used in humbler circumstances.

4 Changes and developments in industry, manufacturing and communications in the nineteenth century affected the lives and material prosperity of millions throughout western society. Among these overwhelming changes were the improvements in the techniques of printing and reproduction that resulted in the development of mass-circulation journals. Periodicals designed to appeal to female readers flourished in both Europe and the United States; these kept their readers informed on the latest fashions and fashionable pursuits. The popularity of Berlin work embroidery coincided with both the rise of a prosperous middle class and the proliferation of periodicals directed to women. It could be considered that this is the reason that Berlin work was the most universally popular type of embroidery of the Victorian era.

Display large image of Figure 2

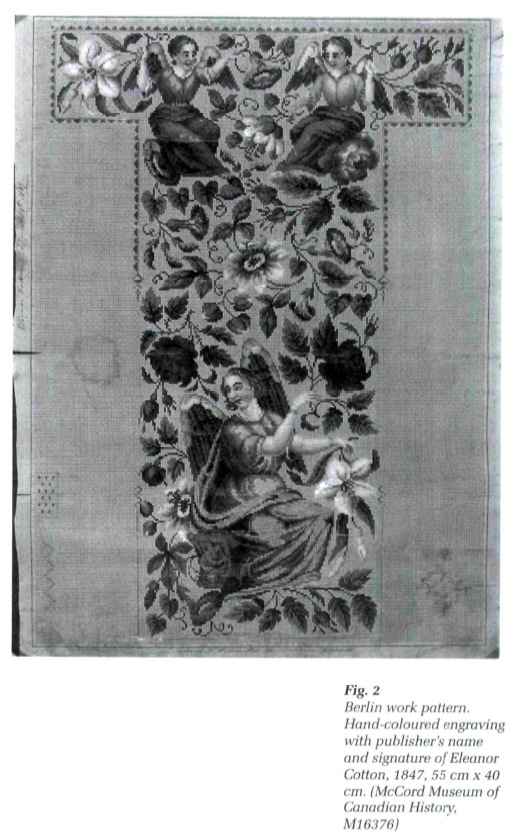

Display large image of Figure 25 Berlin work5 is today known as needlepoint. The name "Berlin work" derives from the fact that the earliest printed patterns for this embroidery came from Germany, which was also the source for the most desirable yarn for this work. A valuable primary source for tracing the development of Berlin work as a popular form of embroidery is the mid-nineteenth-century book just quoted, The Art of Needlework. Writing in 1842, its editor, the Countess of Wilton, titled the final chapter "On Modern Needlework."6 In it she describes the rise in popularity of Berlin work, which she notes "quite seems to have usurped the place of the various other embroideries."7 During the first decade of the nineteenth century, a bookseller in Berlin started to publish embroidery patterns in which designs were individually hand coloured on squared paper. Although these patterns were expensive, they found immediate popularity, and the Berlin work pattern industry was born. By 1840, we are told "no less than fourteen thousand copper-plate designs" had been published. The first large-scale importation of Berlin patterns and yarns into England was made in 1831 by a merchant by the name of Wilks, who is cited by the Countess as her source of information.8

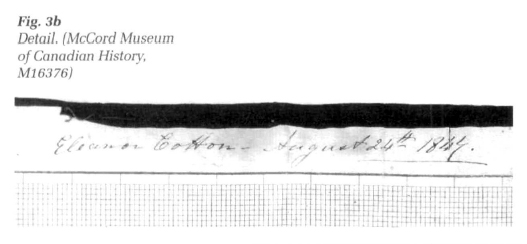

6 An example of a hand-coloured pattern is in the collection of the McCord Museum (Fig. 2). A design for the upholstery of a prie-dieu, it bears not only the imprint of the publisher in Berlin, but an autograph, that of Eleanor Cotton, which places it directly into the Canadian context (Figs. 3a and 3b). Eleanor Cotton (1813-1891) was the daughter of David Ross whose elegant home stood on the Champ de Mars, at that time a fashionable residential square just to the norm of Montreal's old city walls. (Her marriage to Henry Cotton took place in 1847.)

7 In addition to the individual patterns, such as this example, which because of their expense were frequently used time and time again, patterns for various Berlin work projects were included in many of the ladies' periodicals. In North America, Philadelphia's Godey's Lady's Book,9 which was published from 1830 to 1898, kept its readers regularly supplied with patterns and suggestions as to their tasteful application. Other publications such as Peterson's Magazine (1842-1898) in the United States and The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine (1852-1877) regularly included Berlin work patterns, either coloured or in black and white, with printed suggestions as to the colour scheme.

8 These three publications are among those known to have had regular subscribers and readers in Canada, so their patterns would bave been the source of inspiration for many Canadian needlewomen. There were no Canadian publications that offered comparable information to their readers. The Canadian Illustrated News (1869-1883) published the occasional illustration of "Ladies' Work" during its 13-year existence; however these infrequent illustrations had their source in European or American publications.

9 The universal popularity of Berlin work may have been due in part to the fact that the technique required less actual skill with a needle than other forms of embroidery. The basic stitch, which is the one most frequently used, is known as "tent stitch." It is a single simple stitch, rhythmically repeated over the grid of the canvas, the coloured pattern being carefully counted out stitch by stitch. The skill of an accomplished needlewoman reveals itself in an embroidery with a smooth, even surface, free of all irregularities. As the popularity of Berlin work grew, different stitches were invented and added to the repertoire to give textural interest to the surface of the embroidery:

10 As the popularity of Berlin work grew, the modifications of these five basic stitches grew in number. Fanciful names were used to identify these stitches, and the reader can be quite bewildered until a study of the stitch construction reveals its relation to one of the five basic stitches.

11 While Berlin work was typically wool on canvas, silk thread was sometimes used to highlight the design. Beads of glass or cut steel were also utilized as accents or as a decorative fringe: very popular was the use of white, grey and black glass beads to form the principal motif. Beadwork was particularly exacting work since the beads, which were purchased in bulk, had first to be sorted to ensure size and shape were uniform before they were attached to the canvas one by one. Beadwork was frequently used to trim lamp mats or fire screens where the light would give an additional lustre and sparkle to the needlework.

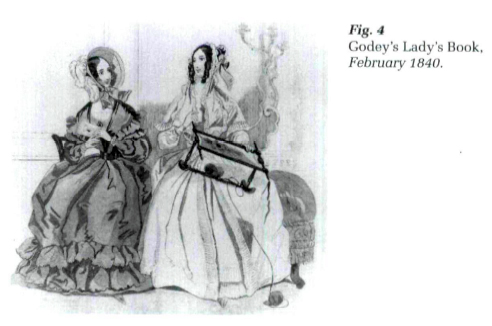

12 The Victorian pleasure in ornamenting every imaginable surface with pattern and texture led to the lavish use of textiles, especially those embellished with needlework. Chairs, foot-stools and cushions were given Berlin work upholstery; each table had its cover, and shelves and mantelpieces were edged with ornamental lambrequins. The man of the house could take his ease by the fireside wearing slippers and a smoking cap ornamented with Berlin work stitchery, his suspenders and cigar case, too, might have been created in Berlin work. In addition to these items, countless other objects were created during the craze for Berlin work: purses, pincushions, table mats, watch pockets, portmanteau straps are among the hundreds of items suggested as projects by the magazines of the day. In all, thousands of miles of yarn must have been used to convert many acres of plain canvas into the patterns so dear to the Victorian heart. In the last decades of the nineteenth century "Art Needlework"12 with its sinuous line and muted colouration eclipsed the brightly coloured, grid-like patterns of Berlin work embroidery. For almost a century, however, Berlin work must have provided many hours of creative enjoyment to women of every class throughout most of Europe and North America.

13 During the nineteenth century, there would have been few homes in Canada without some ornament or accessory embellished with Berlin work. The journals and letters written by Anne Langton during the early years of settlement of Peterborough, Upper Canada, give a lively account of the activities and hardships of pioneer life. In her accounts of the many daily activities essential to survival, there are frequent references to sewing, particularly the remaking of dresses and bonnets along more fashionable lines. Extracts from her September 1840 entries read as follows:

14 The editor of the Langton journals adds a footnote explaining that this refers to the embroidery of a seat and back of a chair, but does not include any other details. It is reasonable to assume that this was a Berlin work project. In early February of the next year, while describing the difficulties of making a satisfactory fire with green wood, and giving a recipe for "an excellent apple-tart" made of dried apples, Langton writes:

15 If Berlin work provided some moments of creative relaxation in a frontier homestead, it is reasonable to assume that the women in urban centres were able to spend proportionately more time at their needlework frames (Fig. 4).

16 In the middle of the nineteenth century, although European mail and newspapers arrived in Montreal regularly (in winter via Boston or Portland, Maine), merchants had to wait for the opening of navigation in April to replenish their stocks. The newspapers of the time reflect in both editorial and advertising content the feeling of excitement at the renewal of mercantile activity after an enforced hibernation. Importers and wholesalers advertised the arrival of their new goods, textiles of every description, including fringes, braids, threads and other trimmings, which formed a large part of these imports. Of particular interest to us is an advertisement of Houghton and May, importers and wholesalers, published in the Montreal Gazette on April 29, 1850. Included in a long list of "New and choice Goods" are fashionable fabrics, such as Spitalfield silks, French bareges, and "8 bales Berlin wool and 1 case Patterns." Merchants from the city, nearby towns and from the rural frontier to the West would have filled their requirements from stock such as this.

17 Victorian Montreal had a number of shops that specialized in fancy goods, laces and "work table requisites," indeed the Mackay's Montreal Directory for 1861-1862 has a separate heading in its index for Berlin wool stores. In this are listed four shops including a Mrs. Footner and Daughter whose advertisement in that directory15 lists in detail their assortment of "English, French and German Fancy Goods" starting with Berlin wool, Berlin Patterns and Berlin Bead work. Also listed in the Mackay index is Mrs. Catherine Walton's "Berlin Wool and Fancy Work Depot" on Great St. James Street. Mrs. Walton's advertisement in the Lovell's City Directory of 186916 states that her business was established in 1844, and the final mention of her store, relocated at 13 Beaver Hall Hill, is in the 1879-1880 Directory. She must have been an astute business woman to have survived, and apparently prospered, over so many years, when so many other businesses failed. That she knew her customers is obvious from an advertisement in the Montreal Gazette in early May of 1850:

18 Many examples of Berlin work that have a Canadian provenance are in the collection of the McCord Museum of Canadian History. The most dramatic, and the piece that inspired this article, is a large framed picture dated 1871 (Fig. 1). This handsome needlework picture is a particularly fine piece of Berlin work, exhibiting the traits of its late, elaborate phase. The exotic bird, the full-blown roses in the floral wreath as well as the extensive use of plush stitch are typical of this late era. The work is entirely done in wool. The background is worked in cross-stitch with double yarn over four crossings of the canvas, the leaves of the elaborate garland are worked in tent stitch, and the flowers and fruit in plush stitch. The magnificent bird of paradise is worked entirely in plush stitch, with French knots detailing the beak and claws. A glass bead forms the eye. The colour palette is rich and the shading subtle. Against the cream-coloured background, the wreath of leaves is worked in shades of olive green and bronze. The lush roses are worked in shades of red, pink and white; the cluster of berries poised over the bird's back is worked in red. Contrasting accents of blue and white form the gentian-like flowers in the wreath. The bird's magnificent tail is in shades of cream and gold, its wings chestnut brown and its breast in shading tones of royal blue.

19 The inscription on the glass identifies the needlewoman as Philomène DeRome. Information received with this donation recorded that she was a student at the Hochelaga Convent between 1866 and 1872. Subsequent investigation has provided more information. She was baptized as Marie-Philomène DeRome in Montreal's Notre Dame Church on September 10, 1857, the day after her birth. Her parents were Léon DeRome and Rose de Lima Simard.18Lovell's City Directory of 1870-1871 lists the family's address as 379 St. Catherine Street, between Amherst and Jacques Cartier streets. Léon DeRome was a well-to-do butcher with a stall in Bonsecours Market. The young Marie-Philomène would have grown up in comfortable surroundings, with music likely an important part of family life. Her father was an active patron of Calixa Lavallée, today remembered as the composer of "O Canada." The musician lived in the DeRome house for a time and later received financial support to continue his studies in France.19

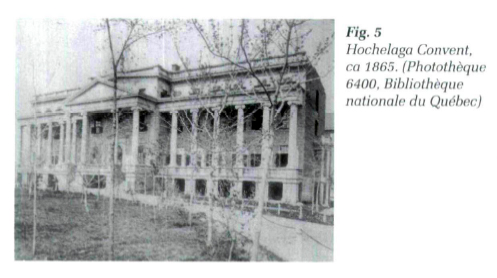

20 In 1866, shortly after her ninth birthday, Marie-Philomène became a student at the Pensionnat du Saint Nom de Marie at Hochelaga, which was "a beautiful village on the outskirts of Montreal... [with] the largest Convent in the province..."20 This convent (pensionnat, i.e., boarding school) was run by the Congrégation des Sœurs des Saints Noms de Jésus et de Marie. In 1860, when the large neoclassical convent building was erected (Fig. 5), this area was still largely rural, and the convent property swept in a green expanse to the St. Lawrence river. An undated prospectus (ca 1880?),21 now in the archives of the convent, emphasizes the attractive and healthy surroundings of the convent almost as much as it does the intellectual and artistic aspects of its curriculum, which, it states, was intended to develop young women with an "éducation solide, soignée et tout-à-fait pratique." The prospectus concludes witii dus paragraph:

A search of the records of the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876 reveals that the Hochelaga Covent was "commended for great excellence in design and workmanship" for its exhibition of embroidered ecclesiastical vestments.22

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 621 That the convent took pride in its needlework is emphasized by the fact that its archives contain many books on the art of embroidery, including pattern and design books, as well as me well-known Encyclopédie des ouvrages de dames by Thérèse de Dillmont.23 It is evident that the students had the best possible instruction in the art of the needle, as prizes were awarded annually for achievement in sewing and embroidery.24

22 An undated portrait of Philomène DeRome was found in the convent archives (Fig. 6). Taken in Montreal by A. Bazinet & Cie, Notre Dame Street, it shows a solemn young girl standing stiffly by a carved table; she faces the camera directly with serious expression, her gaze giving no indication that she has some considerable artistic accomplishment. We have tangible evidence of her skill as a needlewoman, but the convent records25 also show that she was accomplished enough to perform a piano duet at a concert. From her rather plain costume with its crinoline skirt, we may deduce that the portrait was taken in the late 1860s26 when she would have been about 12 years old. In 1871, when Philomène would have been about 14, she stitched with infinite care and patience the image of the exotic bird in its lush floral bower.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 723 Ten years later, in September 1881, Philomène married Edmond Carrière. They settled in Longueuil, a historic community on the St. Lawrence river, to the south of Montreal. Entered in the parish records of the Church of Saint-Antoine de Pades in Longueuil are the dates of her marriage, the birth of her children and her death in January 1892, a few weeks after the birth of her fourth child. Sadly she died before her two daughters were old enough to have learned any needlework from her skilled hands.

24 The Berlin work picture stayed in the possession of the descendants of the DeRome family, and through the years it became a treasured possession, affectionately known as "The Peacock."27 The McCord Museum of Canadian History is fortunate indeed to have added to its collection this beautiful object. A family heirloom has in this way become a part of a national heritage, and from a bygone era a young girl's artistry touches us.