Reviews / Comptes rendus

Vancouver Museum, Making a Living, Making a Life

Guest Curator: Joan Seidl

Designers: David Jensen and Louise St. Pierre of D. Jensen & Associates

Duration: February 1992 to January 1993

Production: Vancouver Museum exhibition staff in co-operation with the Vancouver Multicultural Society

1 The non-Native presence in British Columbia dates back through two centuries to a period when Spanish and British navigators vied to establish their respective territorial claims. That diey sought to rule both land and people over which neither had any right was in their eyes immaterial. Britain's claims ultimately prevailed, and her representative in the area at the time, Captain George Vancouver, acquired a reputation that has grown over time to near-heroic proportions. It was the approaching bicentennial of Vancouver's voyage, coupled with a growing recognition of imbalance in its permanent displays, that led the Vancouver Museum to develop its ambitious exhibition, Making a Living, Making a Life.

2 The exhibition that ultimately emerged, however, had little to do with either George Vancouver or the bicentennial. Instead, Making a Living, Making a Life endeavoured to tell the work stories of immigrants to British Columbia's Lower Mainland in the period 1900-92, while the voyages of the eighteenth century mariners were used only to introduce the theme of "people of many cultures living and working side by side."

3 Developed in consultation with the Vancouver Multicultural Society, Making a Living, Making a Life was a bold attempt on the part of the Museum to redress the omissions in its permanent galleries, to attract an audience more representative of the city's current cultural mix, and to establish longer term relationships with individuals and organizations representative of that cultural mix. Joan Seidl (now the Museum's Curator of History) developed the exhibition in her capacity of guest curator, while D. Jensen & Associates undertook its design. Fabrication and installation services were provided by the institution's own exhibition staff.

4 The exhibition ran for the better part of a year and occupied the facility's vast temporary exhibition wing, a space charged with memories of shows ranging from the spectacular and successful to the meagre and mundane. In many respects, Making a Living, Making a Life belongs more to the latter category than to the former. While the Museum's goal of reaching out to a wider community than that traditionally associated with the institution was unquestionably desirable, the exhibition lacked inspiration, engendered confusion, and revealed a story line more suited to the printed page than to a museum exhibition.

5 In developing the exhibition, the Museum chose a chronological approach over a thematic one, dividing the twentieth century into four historic periods: 1900-09,1910-29,1930-49, and 1950-92. Each of these periods was dealt with in its own separate gallery space, using a combination of textual and graphic panels, dioramas, display cases, and period-room reconstructions. A fifth gallery space was devoted to public programmes and temporary displays of objects from interested community organizations.

6 The exhibition began promisingly enough, with a large and dramatic photo mural of the Spanish vessels Sutil and Mexicana meeting First Nations people at Maguaa in 1792. The accompanying text, paired with a mountain goat horn traded to George Vancouver at about the same time, set the scene for a story about cultural diversity and exchange in Canada's western-most province. On turning into the exhibition's initial gallery, however, one was suddenly thrust into the twentieth century.

7 The gallery's introductory panel summarized the working and racial character of the Lower Mainland in the century's first decade, revealing an area of predominantly British, but of increasingly Asian character, an area in which organized labour was rapidly seizing a foothold and in which the original inhabitants were consigned to a minor and virtually invisible role. Like those elsewhere in the show, however, the introductory panel was heavy on information and light on synthesis, and one was hard pressed to determine die exhibition's central argument.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 18 The gallery's heart was a reconstructed streetscape, depicting a number of turn-of-the-century businesses and shops. Each was defined by a black and white facade, either painted to resemble masonry or produced in photo mural form from historic photographs. Visitors looked through window openings into premises as diverse as an early bookbinding operation and a Chinese rooming house.

9 While the gallery's intent may have been to focus on a city of small factories and small businesses, the streetscape suggested a semi-abandoned village of poorly provisioned shops occupying a false fronted set on a Hollywood backlot. The gallery's feel was two-dimensional, monochromatic, and artifact-poor. The two cast iron stoves and few hanging bits of enamelware chosen to represent Zebulon Frank's hardware store conveyed nothing of the crowded scene depicted in the accompanying three-sided photo mural behind them. The re-created interior of one of the city's early employment agencies was similarly sparse, lacking paper in the typewriter, pens or documents on the desk, a calendar or pictures on the wall, or a waste-basket on the floor. A poor standard of installation, characterized by all-too-conspicuous photo mural butt joints and visible hardware and braces, did nothing to improve the impact of the gallery.

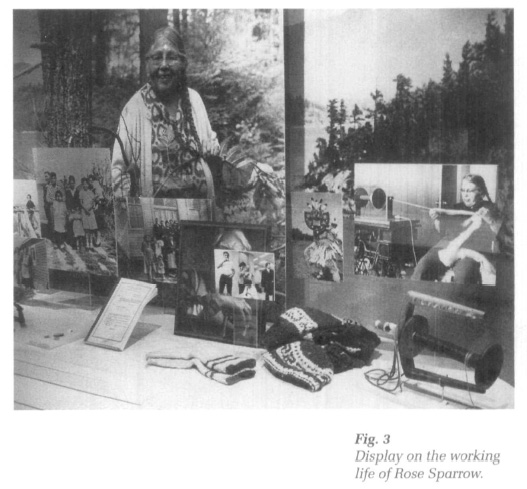

10 The Museum's re-creation of Masuya Nishimura's Japantown grocery store attacked by rioters in 1907, featured in the exhibition to illustrate the anti-Oriental feelings common among the infant city's white majority, was even less convincing, consisting of yet another black-and-white facade, a broken window, a shallow black-painted empty room, and a sloped panel incorporating a too-small-to-be-read account of the riot drawn from the pages of a contemporary newspaper (Fig. 1). A recreation of the Wing Sang Co.'s office was rather more effective, allowing visitors to walk into a room that contained original fixtures from the pioneer import business, though why the display contained a Japanese abacus, rather than a Chinese abacus, one could only guess.

11 The exhibition's second section examined the period 1910-29. Its introductory panel highlighted labour conditions and inter-racial relations in key years throughout the period. The evidence presented depicted a population not "working side by side," but one that was factionalized, and one in which ethnic groups vied for the right to residency and work in the face of hostility and prejudice. The gallery's text and illustrations noted the federal government's illegal sale in 1913 of an urban Indian Reserve, the harassment of German residents at the outbreak of the First World War, rampant unemployment at the end of the war, and the provisions of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923.

12 But the gallery's discussion of the era was incomplete. Its examination of the infamous "Komagata Maru Incident" (wherein a boatload of would-be immigrants from the Punjab were denied entry to Canada and sat in the city's harbour for a period of months before being towed out to sea by the Canadian navy) stopped short of describing its tragic end. Similarly, the text made no mention of the movement for female suffrage or of the changing role of women in the workforce that occurred as much of the area's male population made its way to the Western Front. Work on die domestic front was totally ignored, though central to the lives of close to half the adult population.

13 Despite these omissions, the 1910—29 section of the exhibition had a certain power, largely due to die use of two sets of highly compelling artifacts. The largest of these was die "Iron Chink," a massive machine set in a salmon canning display. As the text explained, it was common practice for canneries to hire both Oriental and First Nations workers at very low rates and to divide their tasks on die basis of race. The fish butchering machine patented in 1905 supplanted many such workers. The name "Iron Chink" persisted, "a backhanded acknowledgement of the skill, speed and fortitude of the workers it replaced."

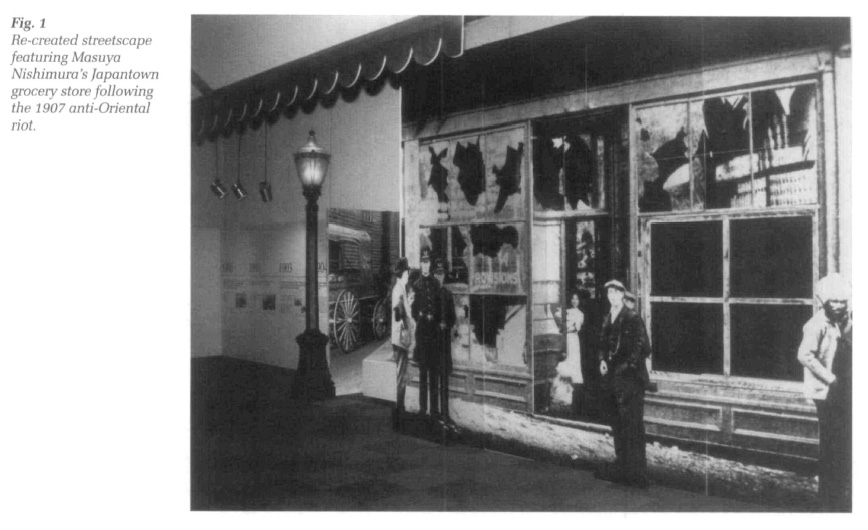

14 A nearby display on early lumbering was even more revealing of attitudes toward race and work. A simple post and beam framework evocative of a west coast lumber mill helped to set the scene. A large photo mural of Japanese Canadian loggers at work in the forest provided context to the familiar tools of the faller's trade: a springboard and axe, a peavey, and a long crosscut saw. A set of brass identity tags used in a Fraser Valley sawmill were among die most interesting artifacts in die display. Each was individually numbered and marked "Chink," "Jap," or "Hindu." Although die Museum's description of how they were actually used was perhaps based more on conjecture than fact, it remains clear that the mill's European supervisors were unprepared to acknowledge that their Asian workers were individuals with names, feelings, and traditions worthy of respect. The term "Chink" was an overtly derisive one, while "Hindu" was at best inaccurate and at worst insulting to the Sikhs employed in the mill.

15 The gallery's subsequent displays dealt with the themes "Cultural groups prepare members for work," and "Cultural groups support their people at work." A combination of text and graphics described how organizations, such as the Sons of Italy, assisted widows and families and how a local Swedish-language paper provided recent immigrants with information on conditions in the city. None of the printing equipment shown was identified or discussed through labels, while the banners of the Italian benevolent societies were hung too high for full effect.

16 The third section of the exhibition dealt with the years 1930-49. While this period may have had a certain historical unity (insofar as it included the troubled years of the Great Depression and the Second World War), the rationale behind die start and end dates of the exhibition's sections was never made clear. What made the period 1950-92 a historical unit? What happened in 1910 that made the city a different place than it was in 1909? What made the years 1900-09 a relevant historical unit rather than die more commonly used years 1900-14? The introductory panels that set the scene for the exhibition's galleries simply didn't tell us.

17 The 1930-49 gallery was the exhibition's largest. Its introductory panel was comprehensive (but poorly placed, being preceded by a display case on the 1942 internment of die west coast's Japanese Canadians). The panel's text and graphics described Depression-era labour rallies, women at work in wartime factories, die gradual enfranchisement of citizens of Oriental ancestry, and the large waves of European immigration of the late 1940s. But what the gallery provided was larger than necessary for the material exhibited. Individual display units were disconnected and seemed to float about the space. The traffic flow control evident in the rest of the exhibition was nowhere to be found.

18 The gallery's displays focused on the working lives of seven Vancouver residents, commenting on their backgrounds, tribulations, and achievements. The city's Chinese population was well represented, with a display on Yucho Chow, a professional photographer who worked in the Chinese community for a period of several decades, and with another on Anna Fong Dickman Lam, Vancouver's first accredited and working Chinese nurse (until as recently as mid-century it was difficult for Asian Canadians to receive training in the professions, and it was often impossible for them to find employment).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 219 A display on Steveston boat builder Yoichi Kishi (interned at Slocan in 1942) featured the hand tools of his trade and direct quotations in the text provided that sense of immediacy and personality that museum exhibitions often lack. A "flip book" of photographs of boats built by Kishi and his father offered interested visitors an opportunity to access further information, but like the other flip books in the exhibition, this was mounted far too low for adults to use with any degree of comfort. The fact that the contents of the flip books were often mounted sideways did little to encourage visitors to use them.

20 Other work histories in the gallery featured the tools of Harold Mackay, a Depression-era cooper from Liverpool (Fig. 2) who ultimately found work in B.C. Distilleries, and Nick Bully, a Turkish-born decorator and painter. Their stories, though perhaps representative, appeared mundane in the face of the experiences of the Orientals and felt more like fillers than central features of the exhibition. Bully's tools were numbered and identified through a number and key system, while Mackay's were not identified at all. The curious were instead obliged to hunt through an adjacent flip book for illustrations and descriptions approximating the artifacts on display. In other instances, object labels were placed adjacent to the artifacts they described. This inconsistent approach to labeling was an irritating feature that occurred throughout the exhibition.

21 Much of the gallery's space was devoted to the subject of workers at the Britannia Beach mine, a copper mine just north of the city. A re-created mine shaft dominated the gallery, but was as amateurish and ineffective as it was large and expensive. A walk through the shaft led visitors into a blackened corridor (bereft of any references to mining) and out to a diorama featuring two-dimensional cut-out photographs of miners at work. This section of the exhibition was artifact-poor to say the least, a piston crank drill from the 1920s being its dominant feature. The display's sole truly interesting and revealing element was the accompanying flip book that contained pages reproduced from the mine's personnel records. These identified individual miners by name and origin, presented photographic portraits, and indicated a miner's reasons for leaving the company's employ: "resigned," "fired," "laid off," "dead," "unionism," "strike," "sassy," "too gassy," "too wet," "going logging," "going fishing," and finally, "became a Rhodes Scholar!"

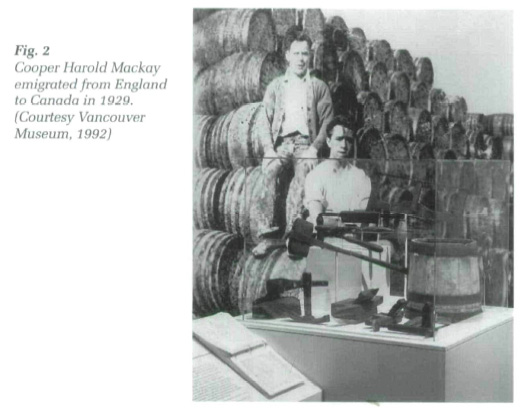

22 The gallery's, and indeed, the exhibition's strongest feature was its section on First Nations. Based on Leona Sparrow's Master's thesis on the work histories of her Coast Salish grandparents, this section was well researched, artifact-rich, effectively displayed, and, above all, highly engaging. Where standard museum practice has been to place any discussion of First Nations' culture at the start of a historical story line, the Vancouver Museum recognized that the Native presence in the city has been ongoing and that Native culture continues to develop. Through artifacts, family photographs, and direct quotations, this section of the gallery examined the Sparrows' working lives as children, young adults, and in old age, showing the parallels between traditional and more contemporary manifestations of various work activities: fishing, logging, harvesting, and crafts (Fig. 3). This was the one area of the exhibition where the Museum appeared to have sufficient artifacts and information to illustrate its theme.

23 The exhibition's fourth gallery examined the period 1950—92, noting that this was a time when predominantly white trade unions reached out toward ethnic minorities, and a time when streamlined and less restrictive immigration policies led to an influx of large numbers of European and, more recently, Asian immigrants. Specific work stories were referenced to illustrate the theme. Following the displays on the Sparrows, this was the least successful section of the exhibition, partly because recent history often lacks the inherent interest of a deeper past and partly due to the emptiness of the exhibitry employed.

24 A display on "Farming as a family business" occupied considerable space, but consisted solely of a scanty text and a farm truck set against a large photo mural. Another, entitled "Practising professional skills," described how federal immigration policy based on points was applied to the case of a West Bengali engineer. The few "artifacts" displayed - drafting tools from the 1960s - may have had a certain association with the engineer and his profession, but they did nothing to illustrate the argument in the text.

25 The largest unit in the gallery featured an existing Indo-Canadian business, Sangeet Video and Gifts. Visitors passed through a recreated storefront and into a room of floor-to-ceiling photo murals, all in black-and-white, taken in Sangeet's South Vancouver store. The effect was both overwhelming and disconcerting. This was a clear case of overkill. The museum had expended considerable resources in creating a display that was essentially empty. lacking both artifacts and interpretation.

26 The interactive display components in the gallery helped only slightly to allay one's perception of a "book on the wall." Instead, one was confronted by a talking book on the wall. A 15-minute video examining the work experiences of individual Dutch, Jamaican, Filipino, and Indian business people was much too long for now exhausted visitors to tackle. The recorded reminiscences of a Lebanese businessman could be listened to through a telephone by those who still had the energy. Interestingly, the gallery's most successful component was its last. An area devoted to the Mosaic job training programme was set up like a classroom, affording visitors the opportunity to follow the paper trails of three immigrants in search of employment. The most poignant of these included 15 successive letters of rejection to a Romanian teacher from a local school district.

27 With the exception of the Sparrow family displays and a few others, it was the community, rather than the Museum, that gave the exhibition its more redeeming aspects. An exhibition and programming area entitled Adding to Making a Living, Making a Life, offered cultural, labour, and other community organizations an opportunity to present themselves to the city. A series of short-term displays, generally conceived and developed by the sponsoring groups themselves, exposed visitors to subjects as diverse as the University Women's Club, Black Women in British Columbia, the National Film Board's Studio "D," and traditional Croatian bagpipes. Though seldom "professional," these displays projected a level of creativity, understanding, and enthusiasm otherwise lacking in the exhibition. These displays, like those in the mainstream exhibition, served as a backdrop for an ambitious series of public programmes, many of which were highly successful.

28 Ultimately, though, an exhibition must stand on its own. Lacking a clearly articulated thesis, a sufficient body of artifacts to illustrate its themes, and a consistent standard of interpretation, Making a Living, Making a Life did not rise to the challenge of its subject. Too small for its space and unevenly designed, the exhibition's greatest success lay in the contacts it made for the Museum in the wider community, a community the institution must continue to serve to secure a meaningful future.

Curatorial Statement

29 Fifteen years ago, when Material History Bulletin 3 (Spring 1977) published a review of the Vancouver Museum's new, long-term local history exhibition, Milltown, both the curator and the reviewer worried about its inflexibility. How could its interpretation, based on expensive, large-scale reconstructions, be altered and added to over time? Those fears have been well-grounded, as the Milltown exhibition continues virtually unchanged to the present day. Meanwhile, both historical scholarship and the character of Vancouver have altered dramatically. By 1990, Museum staff were deeply concerned about the interpretive biases and omissions built into Milltown and the other long-term local history exhibitions, most particularly, the absence of serious treatment of the cultural diversity of the region and the fact that the exhibition story ended in 1912.

30 Given these concerns, and thinking ahead to the bicentennial in 1992 of George Vancouver's arrival on the Lower Mainland, the Museum sought the aid of the Vancouver Multicultural Society. Eventually the two organizations entered into a joint agreement to produce a temporary exhibition for the 1992 bicentennial. For its part, the Multicultural Society saw potential benefits in collaborating with a well-established mainstream institution and particularly wanted an exhibition topic that moved beyond "song and dance." The Museum saw the collaboration as a way to involve the Society's culturally diverse membership in its work and as a potential for longer-term linkages.

31 In the summer of 1990, preliminary contact was made with ten of the larger ethno-cultural groups in the city, and several possible conceptual frameworks for an exhibition were discussed. That fall, the project's steering committee of Museum and Multicultural Society board and staff members chose to pursue one of the ideas - an exhibition based on the theme of work. By February 1991, sufficient funding was in place for the exhibition's opening date to be set for February 1992.

32 From the Museum's point of view, the project had three objectives: to complement the existing galleries by extending and correcting the stories told there; to involve a more culturally diverse audience in the Museum's work in the short term; and to create lasting linkages with culturally diverse individuals and organizations.

33 The theme of work was chosen because it was emphatically not "song and dance" and because it could legitimately include every cultural group's story. The theme could also pick up some of the threads of the story - which the long-term local history exhibitions dropped so abruptly in 1912 - by synthesizing and dramatically presenting already existing good recent scholarship on work, ethnicity, and culture in the Lower Mainland. Preparation for the exhibition clearly pointed out the Anglo-Saxon bias in the Museum's donor pool; it was immediately necessary to borrow artifacts from other regional museums and from local people. Even with this assistance, artifact content was thin in places. Therefore, from the outset it was the story line, rather than the artifacts, that drove the exhibition.

34 Early on plans were to organize the exhibition thematically. This would have the advantage of highlighting concepts such as the role of formal and informal mutual aid. However, the basic facts of the story were so complex (which groups immigrated when and the kinds of work they tended to do) and were so new to most museum-goers, that ultimately a very loose chronological organization layered with broad concepts was chosen. Chronology, it was assumed, would be the easiest framework for visitors to use as they navigated the 836.1 m2 exhibit space.

35 The exhibition was divided into four content areas. The first gallery dealt with the years 1900-09 and its major point was that the Lower Mainland has had a culturally diverse population for a very long time. The second area covered the period 1910-29 and made the point that the resource-based industries of the region were built on the backs of culturally diverse workers. The third gallery dealt with a 1930-49 time frame and considered the matter of work and ethnicity through the experiences of seven individuals. This gallery tried to get down to specifics to pick up some of the ineffableness, such as luck and temperament, that affect people's working lives. The fourth and final section covered the last 42 years, 1950-92, and its major point was the ongoing nature of issues related to work and ethno-cultural background, and it focused on the issue of credentials. Each gallery was introduced by a reference wall that highlighted and explained key dates and events in the history of Canadian immigration policy, race relations, and industrial development. The reference walls were planned so that visitors eager to get to the photo murals and artifacts did not have to pause at all. While nicely designed, the reference walls literally involved "books on the wall."

36 The Museum's second goal, that of involving a culturally diverse audience, was tackled in several ways. First, groups and individuals were involved in the development of the exhibition. The exhibition's theme was so broadly inclusive that it was difficult to prioritize the cultural groups and stories that would, of necessity, receive limited attention and resources. There was the further issue of not kidding ourselves about the nature of the involvement. Could the project seriously involve culturally diverse individuals and groups given its demanding schedule and tight budget ($118.40 per m2 fabrication costs)? In the first instance, the project worked through members and member organizations of the Multicultural Society that had identified themselves as interested in the project. Minimally, the executives of various cultural organizations let their membership know about the project. Several organizations were particularly helpful in identifying individuals with interesting work histories or artifacts and in making referrals within their communities.

37 Some cultural groups did not step forward, so the project initiated contact. This was the case with people of First Nations, most of whom expressed disinterest in projects associated with "multiculturalism." Library research, however, turned up information about a thesis by Leona Sparrow on the working lives of her grandparents Ed and Rose Sparrow of Musqueam. After extensive consultation, Leona and Ed Sparrow (Rose is deceased) permitted the exhibition to quote from oral history interviews, to reproduce family photographs, and to borrow family artifacts. The Sparrow family retained the right to revoke these permissions at any time.

38 Planning for the exhibition had to deal with the reality that no matter how responsive or inclusive the project tried to be, inevitably, groups would be overlooked or under-interpreted. Therefore, several ways to add to and "talk back" to the exhibition were built into the project. People and groups coming forward with additional two-dimensional material, such as photographs and manuscripts, had them easily added to flipbooks located throughout the exhibition. In the core of the exhibition, a 37.16 m2 space was set aside for programming and lined with empty exhibition cases. Cultural groups and individuals were invited to reserve cases for two-month periods to create their own mini-exhibits. The Museum provided some technical assistance with installation and printing labels, but the content and interpretation were left entirely up to the users. These cases proved tremendously popular. Very often groups that got involved installing mini-exhibits also wanted to organize related programmes, meetings, festivals, and demonstrations.

39 From the outset, the exhibition was viewed as a backdrop and setting for community-based programming. A grant from Canada Employment and Immigration allowed the Museum to hire programmers who worked with exceptionally motivated ethno-cultural community groups. School programmes that focused on the exhibition were consistently oversubscribed, pointing to the need for the Museum to extend its offerings in the multicultural area.

40 It is difficult to judge yet whether or not lasting linkages have been created. Certainly, the long-term development of the collection has benefited in that the exhibit provoked new donations from segments of the community that have not donated previously. By the time the exhibit ended in early January 1993, the Museum finally had in hand the artifacts it would have welcomed having in the first place. The less concrete linkages, manifested by a continuing openness to new programming and exhibition ideas, must be demonstrated over the long haul. Vancouver Museum is poised to remove Milltown and its companion "permanent" exhibitions over the next five to ten years. The long-term impact of Making a Living, Making a Life can probably best be measured by the Museum's determination to tell a more inclusive and more flexible story in the future.