Articles

Bringing the Outside In:

Women and the Transformation of the Middle-Class Maritime Canadian Interior, 1830-1860

Abstract

Maritime Canadian interior decoration was transformed between 1830 and 1860 from the austere to the spirited by middle-class women who embraced nature and brought it indoors. Women enlivened the interior with specimens of nature, handmade fancywork and living organisms. By imbuing nature with religious significance and cultural meaning, women were able to rationalize their interest in the outdoors and give purpose to their endeavours. They found inspiration in scientific writings and religious works, including imported journals and ladies' magazines. As women embraced responsibility for interior decoration within their "separate sphere" of the home, they cultivated a comfortable retreat from the vicissitudes of a competitive masculine business world. The enigmatic multidimensional linkages between religion and science, business and home, personal Christianity and domestic aesthetics, as well as faith and feeling are touched upon in this article by using material artifacts as cultural evidence.

Résumé

Entre 1830 et 1860, la décoration intérieure dans les provinces de l'Atlantique a subi un changement radical, passant de l'austérité à la gaieté, grâce aux femmes de la classe moyenne qui ont tiré parti de la nature et l'ont amenée à l'intérieur. Ces femmes ont égayé leurs demeures en y faisant entrer des spécimens naturels, des décorations artisanales et des or-ganismes vivants. En imprégnant la nature de significations religieuses et de références culturelles, elles sont parvenues à rationaliser leur attrait pour l'extérieur et ont donné un but à leurs efforts. Elles ont puisé l'inspiration dans des écrits scientifiques et religieux, notamment dans des revues importées et des magazines féminins. À mesure qu'elles assumaient la responsabilité de la décoration intérieure dans leur« chasse gardée » domestique, les femmes ont construit un refuge confortable contre les vicissitudes du monde du travail concurrentiel des hommes. Les énigmatiques liens multi-dimensionnels établis entre la religion et la science, le travail et la maison, la christianité personnelle et l'esthétique intérieure, de même que la foi et les sentiments sont évoqués dans cet article utilisant les objets façonnés comme témoignages culturels.

1 In the early decades of the nineteenth century, scientific pursuits flourished in Maritime Canada as amateurs began systematically exploring their surroundings. Lists were compiled of animals, birds, fish, insects, fruits, trees, and flowers in an effort to order and classify the outside world. Inquisitive young men joined newly formed popular Mechanics' Institutes in the 1830s, while others dedicated themselves to professional organizations such as the Geological Survey of Canada established in 1842.1 Such scientific explorations of nature were not met by indifference on the part of middle-class Maritime Canadian women who ventured outdoors during their growing leisure time. They embraced nature, copying flowers and leaves in watercolour paintings and sketches. Within the home, fancywork creations mimicked flora as rose petals, leaves and fruits were shaped out of wood, leather, and wax. Birds and animals were stuffed and placed on display in room interiors. As fascination with nature combined with technological progress, living organisms were successfully introduced into the home. Middle-class women, motivated by studies of science and God the Creator, embraced nature and transformed the Maritime home by bringing the outside in.

2 The transition period in which nature was introduced to the domestic interior commenced in the 1830s and reached its apogee in the late 1850s. Women converted interior furnishings in the 1830s and 1840s from the spiritless and restrained to the vibrant and extravagant. This was partially due to changing responsibilities of family members. As part and parcel of the concept of "separate spheres," middle-class wives and mothers became accountable for the appearance of the home, a home that provided a retreat from the stresses and strains of the male working world.2 During this same period there was a proliferation of amateur and popular organizations interested in scientific exploration, such as the Mechanics' Institutes. Women reacted to these developments by linking homely duties to fashionable studies of nature, interpreting their findings in a practical as well as Christian way. They converted home into comfortable haven by embracing nature, promoting Christian values of tenderness, compassion, and affection in the process.

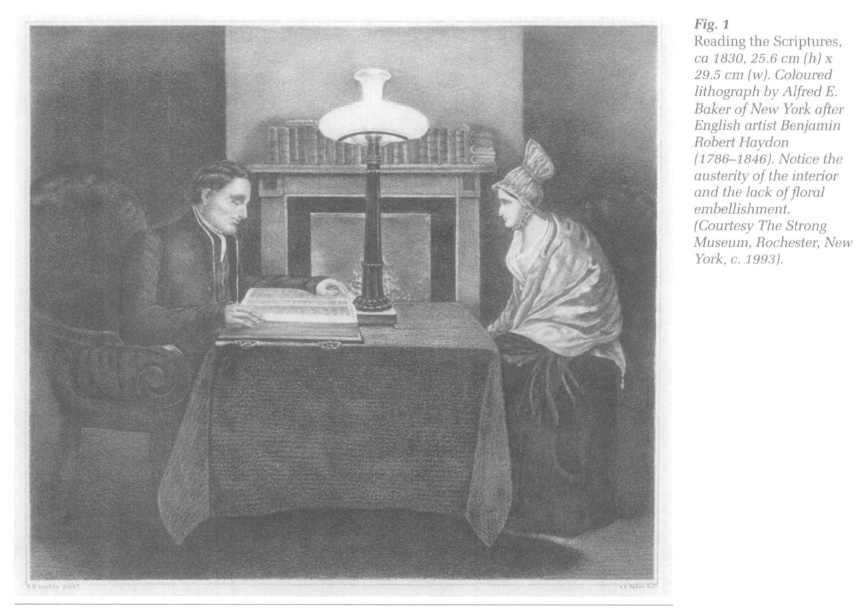

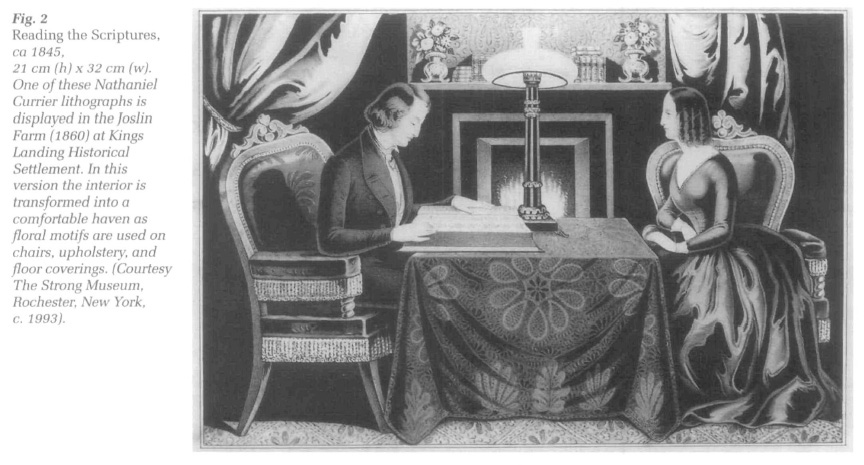

3 The transformation in domestic decoration can be seen by studying two versions of coloured lithographs entitled "Reading the Scriptures." These mass-produced religious artworks were available in Maritime Canada, the first in the early 1830s and the second almost two decades later (Figs. 1 and 2).3 Prints and views of New York were imported into the Maritimes and sold through the Saint John American Literary Agency in 1832. Although it is not known whether these lithographs were among them, the second illustration found its way into a New Brunswick residence and is now part of Kings Landing Historical Settlement collections.4 The lithograph illustrates a man solemnly narrating passages from a religious text, educating his patient and attentive wife. While the theme is the same in both artworks, a remarkable transition has taken place by the time the second was produced.5 The alterations to the domestic furnishings show a clear and fashionable embracing of nature, even though it is apparent that the later print follows a stylized formula. Here now is sumptuous luxuriance, highlighted by the use of botanical motifs in decoration. The wallpaper, table cloth, chair upholstery, and floor covering all have floral themes, and even the carved crests of the chairs are frond-like. On the mantle there are fewer books, replaced by two vases of fresh-cut flowers. The message is simple. The man is the head of the household, as it is he who is reading from the scriptures, but it is the woman who has miraculously turned this home into haven. She has done so in two ways: by arranging fresh flowers and by choosing luxurious manufactured goods bearing botanical designs. Embracing both nature and religion, women made the interior more comfortable and welcoming.

4 Women had become increasingly influential in the decoration of domestic interiors by the mid-nineteenth century. Indeed, it could be said that if "a man ... should hold any decided opinions about decorations or furniture [it] was considered almost improper."6 At the same time that commercial prosperity and urban development transfigured Maritime towns and men turned to the business world, their wives and mothers became increasingly influential within the home, to the extent that it was now the womenfolk who selected interior furnishings. In the eighteenth century:

5 Women's place within the home was confirmed as they were given more domestic responsibilities in addition to interior decoration assignments. They became accountable for the maintenance of the household, as well as the comfort, education, and Christian up-bringing of the residents therein. Indeed, they were the creators of a retreat from the vicissitudes of a commercial world, providers of a comfortable and morally uplifting environment in which men revitalized themselves. The "separate spheres" evolved with men working in an external and hostile commercial world and women creating a peaceful domestic retreat from it. In accordance with these changing and distinctly separate social roles, women turned to nature in the transformation of the domestic interior in order to make the home more welcoming.

6 These household responsibilities were more strongly demonstrated in middle-class households. Middle-class women could devote their energies to collecting and reading about nature at their leisure. As husbands, fathers and sons became more active in the prosperous external commercial world, women found their niche within the home.8 Now time and education, rather than money, defined class. Middle-class women could distinguish themselves from working girls in that they had the opportunity to devote their energies to reading, collecting, and decorating. While working-class girls could purchase machine-made goods with their wages, they could not obtain home-produced wares such as fancywork handicrafts, which showed loving attention to detail. Without these wares in working homes, potential suitors were not as impressed with their prospective partners' abilities - for they saw little on display. Middle-class women differentiated themselves from the lower-classes by using their decorative abilities as badges of respectability and higher social standing. They were also differentiated from less educated working-class girls whose time was spent in paid employ. Some poorer households relied on extra familial income, rendering it more difficult for girls to participate in domestic fancywork traditions. However, middle-class women did have the leisure time to dedicate to a diverse assortment of pastimes and also the education with which to embrace both scientific and religious works.

7 The study of science was popularized in the early nineteenth century as religion and nature were linked together. Journals and periodicals published in England and the United States addressed such contemporary issues, but it was not until 1830 that a New Brunswick publisher placed a notice in the local newspaper calling for a Canadian equivalent. Saint John publisher Henry Chubb lamented the lack of monthly periodicals in New Brunswick, recognizing the need for a "channel of communication between the religious, scientific and learned men scattered throughout the province." He bemoaned the fact that in this "advanced period of the establishment of the Province, and more especially in this peculiarily [sic] illuminated era of the world" that "so little attention is paid to, and so little anxiety evinced for, the literary improvement of this fast-increasing community." Chubb proposed a new publication entitled The New Brunswick Monthly Magazine, and Christian Intelligence as a Maritime alternative in which "politics and that heterogeneous conglomeration [that] usually denominated news, will be excluded."9 Submissions discussing religious and scientific topics were called for from maritime men.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 18 Zoologist Philip Henry Gosse (1810-88), writing in London on the flora and fauna of Canada, likened nature to God in his Canadian Naturalist of 1840.10 Others saw biblical works in terms of the revelation of God's natural talents. "The Bible is not only the revealer of the unknown God to man, but His grand interpreter as the God of nature. In revealing God, it has given us the key that unlocks the profoundest mysteries of creation, the clue by which to thread the labyrinth of the universe, the glass through which to look 'from Nature up to Nature's God'."11 Indeed, nature served to glorify God, for it was said that the "herbs of the valley, the cedars of the mountain, bless Him: the insect sports in His beam; the bird sings Him in the foliage;... the ocean declares His immensity.... There is a God. All nature declares it!"12 Such writings linking the study of nature with the study of God found their counterpart in Canadian books. By 1845, William Thomas Wishart, Maritime writer on Christian doctrine, claimed that nature and God were so intimately linked that by 1845, his followers believed that those who studied science and failed to find God were missing the obvious. James Paterson, Church of Scotland minister, local teacher, and part-time naturalist in Fredericton, agreed, claiming that thoughts on nature could only lead to thoughts about nature's God.13

9 In Saint John, Jacob S. Mott sold volumes at his printing office in the early nineteenth century including the Gospel of Nature.14 Other religious works with natural history emphases were published such as Bible Quadrupeds, or the Natural History of the Animals Mentioned in the Scriptures, a volume that a New Brunswick newspaper advertiser claimed "ought to be possessed by every Christian family."15 This book, along with other religious writings, was available from store merchants G. & E. Sears on King Street, Saint John. Natural histories without any overt religious emphases were also available: A System of Natural History, Containing Scientific and Popular Descriptions of Man, Quadrupeds, Birds, Fishes. Reptiles, and Insects, compiled from the works of the "celebrated naturalists," could be obtained from Charles B. Cox, a Saint John merchant, in the 1830s.16 All these publications encouraged familiarity with God's nature and became part of the Maritime literary tradition, a tradition that inspired interest in science.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 210 The literary sources that advocated the copying of nature and the development of women's handiwork were equally diverse. An assortment of published articles encouraged women to use their hands in the construction of an extensive variety of objects. For inspiration, educated women looked to British etiquette books and less expensive American magazines, which were readily available from stores in Maritime Canada. For example, the Prince Edward Island Summerside Journal reminded ladies that subscriptions to the popular Philadelphia Godey's Magazine and Lady's Book had to be renewed at the cost of $3.00 in advance.17 An assortment of foreign works, including Harper's Magazine, could be sent by mail to subscribers in "any part of the country," according to an advertisement in Ross's Weekly.™ Articles encouraging females to be creative with their time were standard in these, for it was claimed that activity and occupation of the mind induced cheerfulness and productivity. Writers warned that "indolence of habit creates gloominess of manner and acerbity in temper, and induces those diseases which create and increase the evil and prove more injurious to the character and person than sickness itself."19 This literature motivated women to undertake a variety of fancywork tasks as a means of self-fulfillment. Middle-class women turned to nature itself for further inspiration.

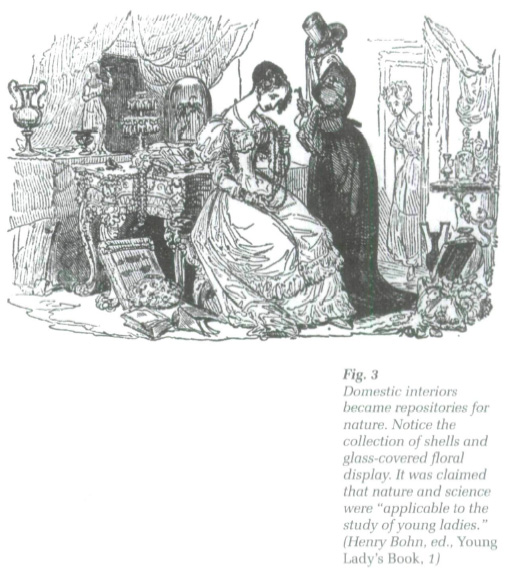

11 Maritime Canadian women collected small treasures such as shells and fossils, as well as flowers and plants, and used domestic interiors as repositories for nature. A British publication available in the Maritimes, and currently in the research collection of Kings Landing Historical Settlement, noted this universal passion for collecting and how it was changing the embellishment of the domestic interior. Henry Bonn's Young Lady's Book, originally written in 1839 expressly for his female friends and relatives, opens with a conversation between him and his cousin Lady Mary. A revealing description of a contemporary and fashionable boudoir (Fig. 3) then follows:

Having described this surprisingly well-ordered interior teeming with life, Lady Mary goes on to inquire what the editor plans on including in his book for young ladies. He exclaims:

Women were encouraged to study, collect, and display nature. Despite overloading rooms with natural specimens, women were able to construct order within seemingly chaotic and confused interiors. These developments occurred at the same time that the exterior world was systematically and scientifically being categorized, and they contributed to an early Victorian desire to organize and control life.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 312 Constant scientific revelations about nature between 1830 and 1860 necessitated revision of the Young Lady's Book, which described in great detail the recent findings of geologists, mineralogists, conchologists, entomologists, and ornithologists including long lists of species classification. The work was updated before the sixth printing in 1859 "in consequence of the necessity which had arisen of revising the whole work in accordance with the improved condition of science."22 Investigative treatises on recently explored fields were announced. "Few men, or none, can thoroughly master all these branches of ... research, but everybody should be acquainted with the outlines of science."23 In the decades preceding the mid-nineteenth century, such explorations and publications made scientific study fashionable for women and encouraged the embracing of nature at home.

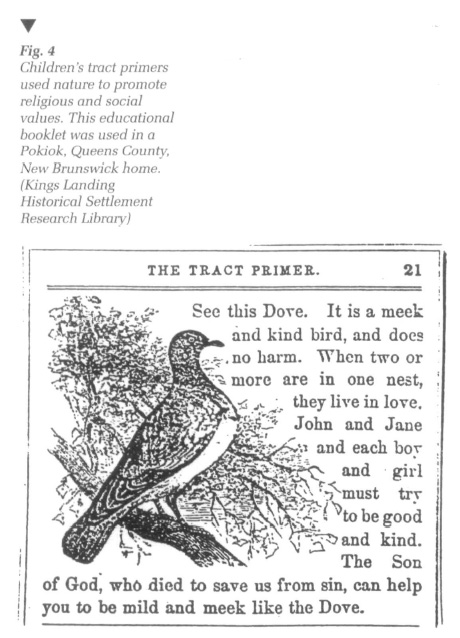

13 Women also addressed their role as moral guides by using their familiarity with advances in science to instill in children the importance of God. They turned to educational booklets called tract primers, which embraced creationism, teaching youngsters that "God made the earth, and the sea, and the sky, and all things in them, in six days; and all that was made was made very good.... He made man and the beasts of the field, the fowl of the air, and the fish of the sea."24 By 1860, Charles Dawson, Nova Scotian geologist and anti-Darwinian, believed understanding science was essential for interpreting God's true powers, as nature and revelation were products of the same author. Dawson wrote Archaia; or, Studies of the Cosmology and Natural History of the Hebrew Scriptures in which he argued that God created earth in six days - not our days, but geological eras.25 Although a revolutionary concept in its time, Dawson clung to creationism in the face of evolution by studying natural phenomena in detail. In such a cultural climate it was justifiable that women study natural history and Christian works as it brought them and their offspring closer to understanding God.

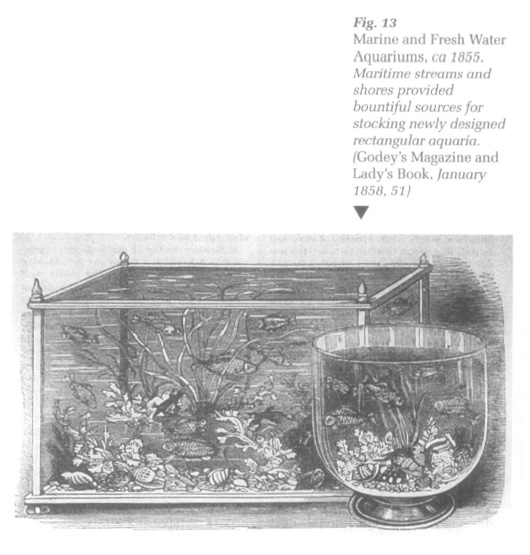

14 Women could impart religious teachings to their children by using nature to an advantage. Tract primers for children explained Christian social values by comparing doves with boys and girls. The birds were imbued with biblical meaning and cultural significance. For example, a Pokiok, New Brunswick-owned children's primer explained some social values by comparing doves with children (Fig. 4):

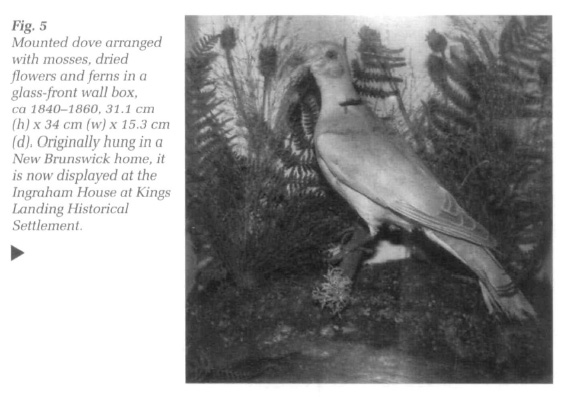

An example of such a stuffed turtle dove or ringnecked dove in a wall mounting could be seen in a New Brunswick parlour in the mid-nineteenth century (Fig. 5). Nature represented the personification of religious and cultural values, becoming an integral part of Christian household life in both educational texts and parlour displays.27

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

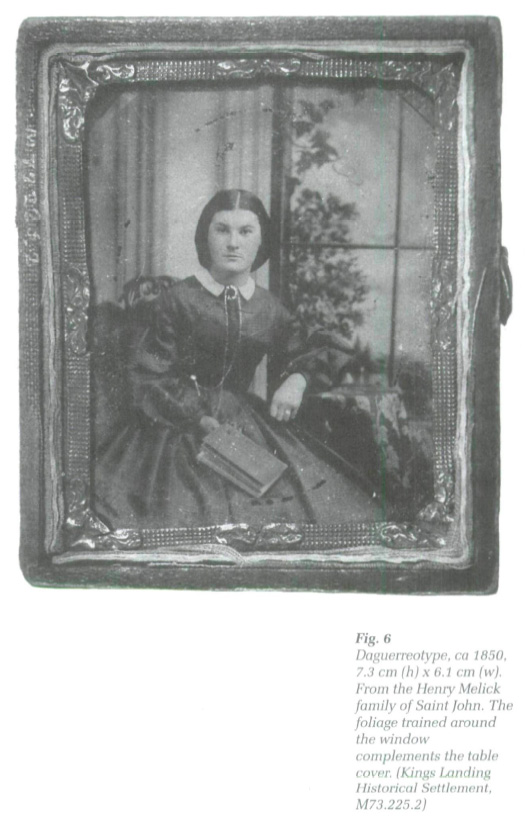

Display large image of Figure 515 Women were encouraged to dedicate themselves to their own study of nature. Horticultural diversions, delicately calculated as "elegant and interesting pursuit[s]," brought women closer to God the Creator. More than this, studies of nature inspired tenderness and caring, prime female traits. These traits were highlighted when flowering plants and trees surrounding the domicile were invested with serene and peaceful qualities: "home, that paradise below/Of sunshine and of flowers/Where hallowed joys perennial flow/By calm sequester'd bowers."28 Residences surrounded by blossoming gardens provided havens as tranquil nature transcended the complexities associated with the working world, providing men with calming retreats at the end of their day. Women looked to nature for assistance in this task. Indeed, the garden was so imbued with comforting significance that women were encouraged to bring nature inside the family dwelling itself, after having first encircled exterior walls with foliage. For example, The Young Ladies' Treasure Book advised women to grow ivy. "Whenever it is possible, climbing plants should be trained up the house and round the windows."29 Such horticultural pastimes became popular at a time when inside-outside architectural boundaries were being broken down, and it became increasingly fashionable to bring as much as possible from the outside in.30 In a daguerreotype of an 1850s Saint John interior, a young lady sits by a table that is covered in a leaf-patterned fabric, while outside living foliage enwraps a window frame (Fig. 6). Contemporary literature available in the city claimed that once the house was thus en-wrapped. childhood could nestle within "like a bird which has built its abode among roses; there the cares and the coldness of the earth are, as long as possible averted. Flowers there bloom, or fruits invite on every side ... this new garden of the Lord ... [with] trees of the Lord's planting, bear ... fruit to His glory."31 Women turned home into haven for their husbands and children by associating nature with nurturing in the name of God.

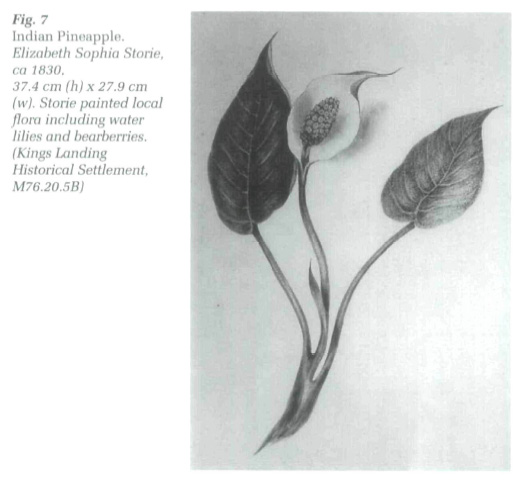

16 This flourishing interest in scientific investigation and studies of nature encouraged personal inquiry, drawing women out of the household to experience nature first hand. In Maritime Canada women explored fields and woods on daily outings, accompanied by friends and kinfolk. Sketching and painting nature became a popular pastime. In New Brunswick, Elizabeth Sophia Storie was escorted by J. E. Woolford on her excursions along the Saint John River Valley. She was the wife of John Simcoe Saunders, and Woolford was the barracks master in Fredericton between 1824 and 1858. Together they sketched and painted plants and flowers such as the Indian turnip, azalea, Indian pineapple, lady's slipper, purple trillium, bloodroot, violet, and water lily (Fig. 7).32 Trees, shrubs, fruits and leaves became subjects of study. Storie painted beech and black birch leaves, and fruit from bearberry bushes.33 Composed in the 1830s, some were framed and brought into the domestic interior. The choice of subject matter showed individual taste and refined upbringing while the display of work in the parlour showed friends and family alike the accomplishments of Christian household members. The domestic realm became aesthetically uplifting and indicative of individual achievement as homemade representations of nature painstakingly laboured upon raised the cultural tone of the Maritime Canadian interior.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 617 In Nova Scotia, Maria E. (née Morris) Miller (1813-75) opened a drawing academy and spent many hours producing watercolour illustrations of local wildflowers.34 She studied with Professor W. H. Jones of Dalhousie College and miniaturist L'Estrange. Her original watercolour paintings of flowers were collected by the Halifax Mechanics' Institute and later became part of the Nova Scotia Museum holdings. Between 1840 and 1867, three series of her paintings were printed as hand-coloured lithographs in London under the patronage of various Lieutenant-Governors of Nova Scotia. Indeed, notables such as Sir Colin Campbell and Samuel Cunard were reputed to have aided in their publication.35 Local botanist Titus Smith, the "philosopher of Dutch Village," brought Miller specimens and encouraged her work. He wrote the botanical notes accompanying her 1840 edition of The Wild Flowers of Nova Scotia, while Alexander Forrester, Presbyterian minister, revised the text in the 1853 second series, George Lawson, of Dalhousie College and founder of the Botanical Society of Canada in 1848, revised the third edition. Such involvement by recognized figures encouraged not only Miller, but other women, to paint and study nature. Such drawings were imbued with cultural meaning. Reviews in the Nova-scotian effused about Miller's work of which it was claimed that anybody displaying it in parlour or boudoir helped prove familial taste and patriotism. Capturing the beauty of the land was a fine and honourable accomplishment for Christian ladies, and when art was presented in a prominent parlour location it could not fail to impress visitors. Indeed, a romantic aesthete wrote in the same newspaper article that he would be tempted to marry the daughter of any family who displayed Miller's natural renditions!36 As a key to social success the art symbolized Christian goodness and virtue. Such taste and perception of beauty was related to the moral development of the individual. Considering the connection between God and nature, could an immoral woman create such delicate artwork? Parlours increasingly reflected women's personal talents and individuality in the meticulous attention to detail their artwork displayed. Christian approbation emanated from the choice of which natural displays and fancyworks were to be found in such domestic interiors, as women brought renditions of nature from the outdoors in.

Display large image of Figure 7

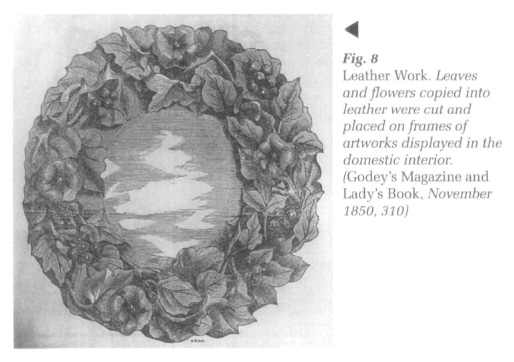

Display large image of Figure 718 Apart from mimicking flora in paintings, handiwork was also inspired by nature. Designs for fancywork products were enhanced by ladies' journals, which encouraged copying flowers such as roses, daisies, violets, and pond lilies. Author Mrs. Jane Weaver instructed readers on how to assemble roses made from wood shavings by using wire, thread, scissors, and glue in the 1858 edition of Peterson's Magazine. Another newly fashionable female accomplishment was the home-manufacture of leather flowers, which were used to decorate frames for mirrors and works of art.37 Sheepskin was used to make foliage as natural leaves and shaped paper cut-outs were used as guides. By no means a quick and easy task, the leather had to be prepared, shaped, softened in water, pressed in cloth, veined with a blunt pen-knife, dried by the fire, dipped in warm home-made size, dried again, and applied onto an already prepared wooden frame. Pressure was then employed using coarse silk twisted over a wooden plate or bowl as the glue dried. Several layers of varnish were applied (Fig. 8). Such attention to detail and perseverance in tasks were features of women's work. Indeed, the existence of examples in the New Brunswick Heritage Collection Centre testifies to the complex and delicate nature of such products.38 Self-satisfaction and individual distinction intensified with such feminine diversions. These pastimes emboldened women at a time when they perceived their identities diminishing in the face of competition from de-personalized, mass-produced factory wares. Women retained a sense of self-value by building up their artistic proficiency and by embracing nature in the decoration of the home.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 819 Women rewrought nature with a controlling hand by garnering an increasingly diverse potpourri of accomplishments. Some persevered in handicrafts, painting on velvet, glass and ribbon, while others made patchwork quilts and needlework pictures. Artificial fruits were made from coloured cloth and knitting wool stitched over wire frames. Fruits were shaped out of wax, pastry and plaster. Mr. A. Stumbles, recently arrived in Prince Edward Island in August 1832, taught a broad range of accomplishments to the locals including the making of artificial fruits "executed with the most accurate resemblance of nature," as well as the crystallization of fruit and flower baskets.39 In New Brunswick, Mrs. Clark ran advertisements in a local Saint John newspaper in October 1842 notifying the public that she had "opened a school for the instruction of young ladies in the elegant accomplishment of preparing wax fruit and flowers," which she taught in six lessons. Private lessons were offered to ladies at their own residence if required.40 In Halifax, Maria E. Miller taught lessons in watercolours, pencil and chalk, instructing the individual how to arrange fruit, bird, and flower designs on velvet, satin, and paper. Out of the chaos of the outside world women took nature, tamed it, and presented it in an orderly manner in a way that recaptured the natural and simple in an age of machines.

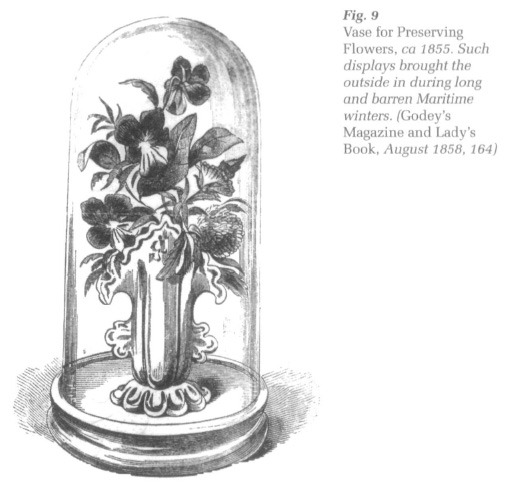

20 By the 1840s Godey's Magazine and Lady's Book gave instructions for using shells in wreaths and bouquets to be framed under glass (which protected delicate works from dust). Procuring shells locally was easy: "they may be picked up in hedges and on banks; drawn out of ponds and rivers, along with weeds; collected on the sea-shore, or among rocks; or they may be found among the refuse in fishermens' [sic] nets."41 Maritimers were well placed to explore local shores and waterways. The collections could then be "kept in small trays, in shallow drawers of equal depth; and such specimens as are too large for the drawers, will ... [form] a handsome article of furniture arranged in a glass case."42 Rocks, shells, and wax flowers placed on display could last a lifetime. Such works preserving samples brought indoors could also be made by women as "Next to the pleasure of collecting in the fields, is that of seeing specimens preserved neatly and in good order."43 An article in Godey's Magazine and Lady's Book in August 1858 suggested keeping floral specimens in alcohol inside sealed glass jars. Another way of preserving flowers was to coat the stems with wax and place them in porcelain jars that stood on wooden bases under glass domes (Fig. 9).44 This ladies' magazine claimed such displays would last for a year, bringing the outdoors in during sterile winters. In the Maritimes, where winters lasted five months and longer, the display of such colourful and everlasting articles was energizing. Indeed, the same author writing on the preservation of flowers in 1858 claimed that for the female invalid the vases recalled "the sunny skies and green fields of summer;... as she looks upon them ... she can forget for a time the snow-clad, ice-bound trees and fields around her." Women embraced nature and scientific advances as a way to transform the interior into a place of comfort and beauty year round, for the healthy and the suffering alike.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

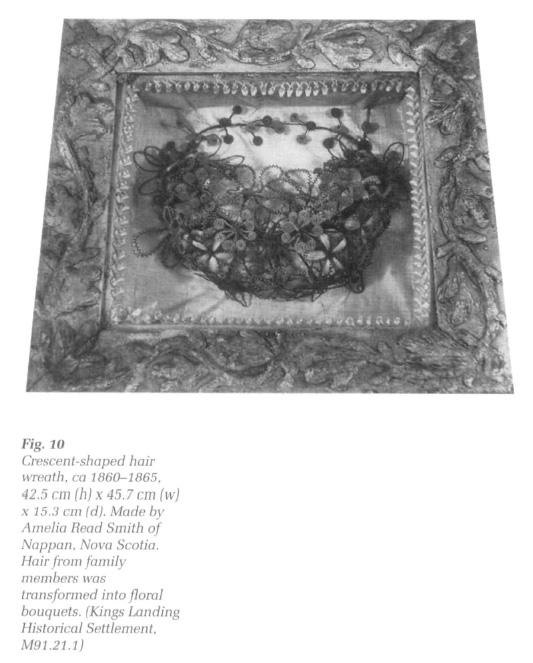

Display large image of Figure 1021 Another way to occupy women's by-no-means-idle hands in the 1850s was in the fabrication of framed hair wreaths. Designs were made from hair clipped from family members, often folded into floral patterns with wire, wax flowers, dried leaves, and coloured beads. Sentimental fancywork such as this became mournful souvenirs as family members passed away; ameliorating the painful loss of a loved one. Such romantic concepts denied unexpected changes in family life, providing ways to continue the memory of familiar characters after they had been removed from the domestic landscape. Kings Landing Historical Settlement has wreaths made by Christine McAlpine of Cambridge, Queens County, New Brunswick, and Amelia Read Smith of Nappan, Nova Scotia (Fig. 10).45 Raised leaf and vine motifs decorate the gesso frame of the latter wreath. The wreath itself is fabricated from different coloured hair, hair that seemingly captures the spirit of its owners. Women having time to devote to such endeavours could laboriously lavish attention on detail, the resulting floral displays revealing their fascination with nature.

22 Middle-class women also manufactured an array of articles with designs taken from nature using their skills as seamstresses. They adorned articles such as sofa cushions, headrests, table covers, toilet sets, lace scarves, whisk-broom holders and bookmarks with designs inspired by nature. Small emery bags used for cleaning rust off needles were made in the shape of crabs, tomatoes, strawberries, and daisies.46 Pincushions were made in fruit and bird shapes, and some were even fashioned in the form of rabbits.47 Exotic birds were used as design sources, copied into brass, and plated with silver or nickel. Used in connection with clamps, such household goods were known as sewing birds or hemming grippers. These articles were used to hold lengths of cloth and netting while being hemmed by female hands.48 A brass hemming grip in Kings Landing Historical Settlement collections, about 7 cm in length, has a swallow fastened to the top of the clamp shaft.49 By mimicking nature in sewing projects, and using tools that were themselves decorated with birds and animals, women transformed the character of the domestic interior.

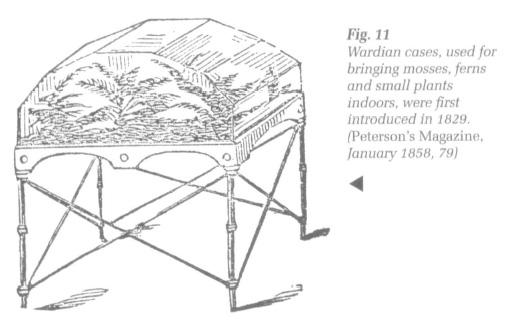

23 Apart from emulating nature by hand in paintings, displays and sewing, contemporary scientific discoveries made it possible to bring living organisms into the home. Although encouraged to bring nature inside, it was not until late in the third decade of the nineteenth century that framed glass cases used for growing mosses and ferns were introduced. Wardian cases, named for London surgeon Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward (1791-1868), made their appearance in 1829. Ward discovered that miniature ecosystems could be constructed within glass frames enabling the transportation and display of living plants.50 The same scientific principles were used to decorate the interior as early Victorian wives and mothers assembled their own miniature gardens in Wardian environments displayed on stands, shelves and mantles.51 Charles J. Peterson, in Peterson's Magazine, commented on the popularity of Wardian cases, two engravings of which were included in the 1858 edition of the magazine. The first Wardian case shown was an inexpensive soup plate with an ordinary bell-glass over it; the second a stand constructed by a cabinetmaker with a simple glass-framed top (Fig. II).52 Described as "ornaments of Nature's own producing," plants and flowers suitably arranged and distributed employed the hand and delighted the eyes of Maritime Canadian women.53 Such natural ornaments found their way into the domestic realm by the mid-nineteenth century; unfortunately few survive in their original state today due to the fragility of glass and the nature of their contents.

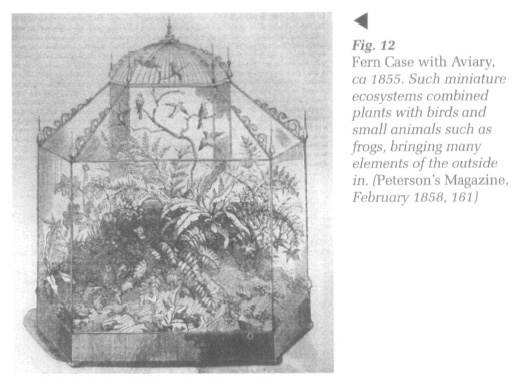

24 Wardian cases could be adapted to hold birds, bringing other living elements indoors. Small birds surrounded by miniature forests formed compact ecosystems. One such display was presented in an imported Peterson's Magazine in the 1850s (Fig. 12).54 Suitable species were suggested for captivity including singing birds such as canaries. However, the Maritime Canadian resident could acquire birds from closer to home, for example, the cardinal and the "cedar bird" or cedar waxwing. French Canadians in New England referred to the cedar waxwing as the "Recollet" from the similarity of the crest to that of the hood of the religious order; once again linking nature to God.55 Elegant enamelled birdcages were imported by F. A. Cosgrove in Saint John;56 other shipments of fancy birdcages arrived the next year from New York.57 This fascination with birds occurred at a time when public gardens were becoming popular. Indeed, Maritime Canadians could study birds in the first zoological garden in British North America by visiting Andrew Downs' 1847 exhibitions on Halifax's North West Arm.58

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 1225 Plants and birds were not the only living entities brought indoors. Goldfish had been introduced to the Americas in the late seventeenth century, but it was not until a hundred years later that circular goldfish globes became fashionable.59 Each globe was referred to as a sort of "crystalline Hole of Calcutta" by one ladies' journal writer because limited oxygen transfer in small-necked jars made life difficult for the fish within.60 Such globes were obsolete by the 1850s by which time scientific studies had proven that rectangular and bowl-shaped aquaria incorporating oxygen-producing plants provided more successful environments (Fig. 13). Such developments facilitated the creation of healthier miniature ecosystems, making it possible to maintain live specimens indoors successfully. Women were able to create and control their own fresh-water and salt-water aquaria, collecting specimens from local streams and shores. It was possible to use their talents as nurturers and civilizers, believing it worthwhile "to domesticate" gobies, blennies and wrasses.61 Women used aquaria to embrace the out-of-doors, giving "the gratification of introducing another element and its beautiful inhabitants into our very parlors and drawing-rooms."62 Women transformed the interior by enlivening it with nature.

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 1326 Middle-class women, motivated by studies of science and religion, embraced nature and brought it into Maritime interiors. Designated to a separate sphere within the household, yet aware of the advances of the outside world, women ameliorated the strains of a society in transition by embracing nature and introducing it into the home. The transformation of the interior into a comfortable retreat was motivated by inexpensive ladies' magazines imported from the United States and etiquette books from Great Britain. Dedicating their artistic skills to the fabrication of paintings and fancywork, women produced a variety of wares for internal display, transforming the appearance of the home into a lively repository for nature. By imbuing nature with religious and cultural meaning, women promoted their position within the Christian home as nurturers, educators, and vessels of virtue. Emboldened by their exploitation of the outdoors and their proximity to God through the study of nature, middle-class women transformed the physical landscape of the domestic realm into that of a comfortable retreat. Women abandoned the austere decoration of former years in cheerful and enterprising home embellishments that mimicked nature. The home was filled with living flora and fauna as technological advances facilitated, for example, the nurturing offish in rectangular tanks as well as plants and ferns in Wardian cases. Without doubt, middle-class women transformed the Maritime interior between 1830 and 1860 by bringing the outside in.

I would like to thank Drs. Michael S. Cross, Judith Fingard, Janet Guildford, David J. Marcogliese, and an anonymous reviewer for constructive criticism of this paper. I am also indebted to Kings Landing Historical Settlement staff, in particular Robert Dallison, Darrel Butler, and Cynthia Wallace-Casey. This article is adapted from a presentation at the LXth Annual Atlantic Canada Studies Conference held at Memorial University of Newfoundland in May 1992. Contemporary texts and artifacts mentioned in this article are from Kings Landing Historical Settlement collections unless specified otherwise. Newspapers were accessed using the Canadian Heritage Information Network (Atlantic Canada Newspaper Survey database), courtesy of the Department of Communications, Ottawa.