Reviews / Comptes rendus

New Brunswick Museum, Music of the Eye: Architectural Drawings of Canada's First City, 1822 to 1914

March 1 - May 1,1991, Public Archives of Nova Scotia, Halifax;

September 6 - October 6, 1991, Nichel Art Museum, University of Calgary;

November 21 - December 31, 1991, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull;

July 1 - September 22, 1992, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John.

1 Saint John, New Brunswick, lays claim to being Canada's first city. A charter of incorporation dating back to 1785 gave legal status to this frontier outpost on the shores of Fundy Bay. The arrival of thousands of British sympathizers following the American War of Independence determined much of the city's Loyalist spirit and Georgian substance. Notwithstanding their bond with Britain, these "loyal" Americans brought something of the cultural complexion of the thirteen colonies with them to the northern wilderness. Among other things, this meant certain views about architecture and the built environment.

2 Despite the ravages of time, a series of nineteenth-century fires and a latter-day scheme for urban renewal, it is remarkable that portions of Saint John still retain something of the port city's colonial charm. Successive generations of heritage enthusiasts from near and far have affirmed the significance of the city's private and public buildings. Over the past decade or so, a growing number of commentaries on Saint John's architectural history have appeared in both popular and scholarly publications. Still, until recently, a systematic examination of the city's architects and their work had not appeared.

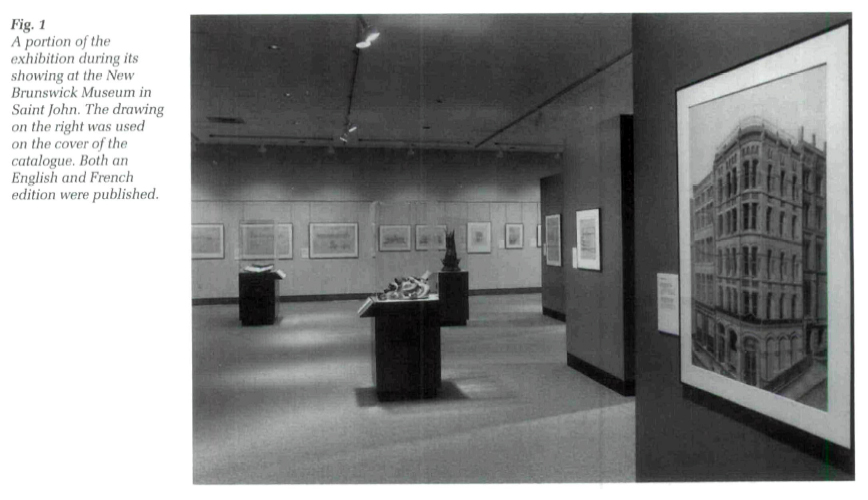

3 The New Brunswick Museum's national travelling exhibition, "Music of the Eye: Architectural Drawings of Canada's First City, 1822 to 1914," and the accompanying catalogue bearing the same title, come together to offer important new information on Saint John's cultural landscape. Curated by Gary K. Hughes, the New Brunswick Museum's Chief Curator, the exhibition consists of 42 architectural drawings covering a variety of building projects between 1822 and 1914. The renderings themselves represent both working drawings and more formal presentation drawings prepared for clients. In the 136-page, fully illustrated (including 16 colour plates), and annotated catalogue, Hughes provides a permanent record of the exhibition itself and offers an extended discussion of Saint John's architectural history. Separate English and French editions of the catalogue were produced in a co-publishing venture between the New Brunswick Museum and the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. Support for the exhibition and catalogue was received from the Museums Assistance Programme, Communications Canada, the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada and the Association of New Brunswick Architects. In addition to showings in Calgary, Hull and Halifax, "Music of the Eye" was featured at the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John in the summer of 1992, to coincide with that institution's centennial celebrations.

4 The exhibition and catalogue seek to develop a particular thesis: Hughes argues that the exhibition's architectural drawings depict the rise to professional status of Saint John architects. This process saw a gradual transition from the early nineteenth-century "builder" to the emergence of the professional architect in the present century. Surviving drawings of proposed buildings signify the interplay among the builder/architect, the client and the particular historical circumstances surrounding the building project. Hughes states that while the builder and architect were "virtually synonymous" until the second quarter of the nineteenth century (p. iii), later the architect began to overshadow the builder by assuming more and more control over the building's design and construction details. The architect was successful in his competition with the builder by employing style, setting, technical solutions, education, management acumen, and advertising to good effect (pp. iii, iv).

5 This thesis is developed through close analysis of a collection of 42 architectural drawings from the holdings of the New Brunswick Museum and a handful of other institutions, including the Public Archives of Canada and the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick. Hughes' premise is that the architectural drawings are artifacts suitable for consideration within a material history paradigm. It is clear that the drawings reflect stylistic considerations. As well, according to Hughes, the drawings can be employed to determine a building's floorplan, construction details, decoration and its site location. Finally, the very medium on which the drawing was executed indicates technical adaptations in the architect's depiction of visual information. All of these factors point to the rise of the architectural profession in New Brunswick's port city (p. iii).

6 Citing evidence from a number of drawings, such as John Cunningham's 1822 neoclassical design for the Henry Gilbert house (Cat. no. 1, p. 4) or Cunningham's 1843 neo-Gothic design for the Reverend S.C. Gallaway's Congregational Church (Cat. no. 6, p. 13), or Matthew Stead's 1858 "Tudor Gothic" design of the European and North American Railway terminal (Cat. no. 11, 12 pp. 35-41), Hughes contests the view that Maritime architects were "cautious, conservative, always a little retardaire" (Shane O'Dea, Acadiensis, 1981). Both exhibition and catalogue contend that Saint John was anything but a "stylistic and technological backwater during the nineteenth century" (p. v), rather, Saint John architects such as John Cunningham (1792-1872), Matthew Stead (1809-1879) and others were among the most progressive Canadian architects of their generation. In an extensive catalogue discussion covering changing architectural styles, building technologies, drawing conventions, biographies of thirteen Saint John architects and detailed captions for each drawing featured in the exhibition, the author explores the historical circumstances related to the emergence of the city's architectural profession.

7 This reviewer visited the exhibition during its Saint John venue. On display in the New Brunswick Museum's new wing, the exhibition consisted of a straight forward arrangement of the 42 works themselves together with a modest tide panel. To complement the theme of the show, there were four display cases featuring selected artifacts such as building ornamentation, three architectural style books from the mid nineteenth century and a collection of architect's drafting implements. The architectural renderings were uniformily impressive in their composition and detail, they revealed a wealth of information on such buildings as the Saint John County Court House, 1824; the Market House, 1837; the Customs House, 1841; as well as a host of other public buildings, churches and private dwellings.

8 The exhibition itself lacked any formal acknowledgements. The only indication of "authorship" and the only references to the professional and intellectual foundations of this exhibition project are found in the catalogue. While an English and French edition of the catalogue was available on a bench in the center of the exhibition gallery, certainly the appropriate scholarly apparatus should have been an essential aspect of the presentation of this exhibition.

9 Those viewers who did not consult the exhibition catalogue may have found the show's title somewhat confusing. There was no attempt to account for the rather presumptuous phrase found in the exhibition's subtitle, "Canada's First City." As well, no explanation was offered for the reasoning behind the title's cutoff dates, 1822 to 1914. Why does the exhibition cover only 92 years in Saint John's history? Although they seem somewhat arbitrary, one is left to conclude that the dates for the exhibition were determined on the basis of the availability of surviving drawings. Is this so, or were there other considerations? These issues should have been addressed in the exhibition itself.

10 The curator states in the catalogue's introduction that the architectural drawings can be appreciated not only as archival documents, but significantly, as artifacts, (p. iii). Notwithstanding this contention, there was little in the presentation of the exhibition to underscore this notion. The manner of display and overall ambience of the works themselves was reminiscent of a traditional archival exhibition. One would have hoped for a more imaginative exhibition concept so as to further elucidate underlying material history themes contained in the drawings. That the architectural drawings contain certain artifactual qualities might, indeed, be suggestive of various research strategies. But how, in specific terms, should these architectural drawings be subjected to intensive material history analysis? Coverage of these key issues was elusive at best.

11 By definition, a case study's focus is limited to the topic at hand. Still, the impact of this exhibition would have been enhanced (particularly for a national audience) through more emphasis on comparative analysis. If, as curator Hughes argues, Saint John was anything but a cultural and architectural "backwater," why not demonstrate this point via selected comparisons with other North American cities? Although the catalogue addresses this concern somewhat more successfully, the exhibition itself presents a panorama of Saint John architecture — but in a virtual vacuum. Deliberate comparisons with nineteenth-century Halifax, Charlottetown, St. John's, Quebec, Montreal, Portland and Boston, for example, would have provided an informative counter balance within the overall exhibition presentation.

12 These technical objections aside, the New Brunswick Museum's national travelling exhibition, "Music of The Eye," succeeded in bringing together a remarkable collection of architectural drawings for inspection and enjoyment by a cross section of Canadians. This achievement, together with Gary Hughes' handsome exhibition catalogue, has made an important contribution to our appreciation of the architectural heritage of Canada's first city.

Curatorial Statement

13 The national travelling exhibition "Music of the Eye: Architectural Drawings of Canada's First City, 1822 to 1914" and its accompanying catalogue attempted to trace the architectural history of Saint John, New Brunswick, during the stated timespan through the medium of the architectural drawing. Since the travelling portion of the exhibition was two dimensional, consisting of drawings arranged chronologically, its interpretation depended largely on the catalogue. Exhibition venues included Halifax, Calgary, Ottawa-Hull and Saint John but only in the last centre were the drawings supplemented with pertinent artifacts and photographs. While these selections enhanced themes explored in the catalogue during the exhibition's showing at the New Brunswick Museum, care was taken not to distract the visitor from the primary content, the drawings themselves. In Saint John, therefore, supplementary artifacts and visuals were kept to a minimum and the drawings emphasized through an illustrated lecture series that explored various aspects of architectural history suggested by the graphics on the gallery walls. In other centres, the curator, where possible, delivered illustrated lectures based on themes developed in the catalogue.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 114 While some of these themes might have been obvious to the museum visitor through inspection of the drawings — stylistic and technological development, for instance — a fuller understanding could only have developed through the printed word. Rather than depend on lengthy captions, these were kept to the essentials of identifications and an expanded catalogue written instead. Its organization was textured so that it might appeal to both the casual visitor or the scholar. Beyond the introductory essay, each work in the exhibition was reproduced photographically in order of date and, as far as possible, the information structured to permit an easy entry and exit where desired. The opening paragraphs usually concentrated on the details of the building project itself from gestation on the drawing board to completion or, if not completed, the factors that influenced this result. This placed the project in the context of local history by relating factors such as the architect involved, other drawings produced for the same building, location, cost, economic climate, politics, state of the construction industry and the building's ultimate survival or destruction. As discussion proceeded, some or all of these factors were introduced to broader considerations beyond the local context, including style and building technology. Finally, the featured drawing was examined, including its intended audience and use, graphic style, support medium, production features and its significance to the overall building project.

15 The 42 drawings in the exhibition and catalogue were chosen to cover a time span which the curator felt to be the most significant period of architectural development in Saint John. Since each drawing was meant to stand on its own, the narrative glue connecting this chronological development was provided by biographies of the architects involved in the catalogue. Education, travel, foreign working experience, graphic style and career details involving all other known commissions in the Saint John area were related to supply context for the drawings selected. Photographs of the architects responsible for the commissions were included, where possible, as were historic and contemporary visuals of the completed projects for each caption entry. The latter, of course, depended on the survival of historic images in archival files or the survival of the buildings themselves. A number of these images were featured on the gallery walls during the Saint John venue to assist in the interpretation of the exhibition.

16 A primary objective of the research phase leading to the selection of the drawings and the catalogue was to make the base of enquiry sufficiently broad. As noted previously, this went beyond an analysis of style in one community and included other variables that placed the patterns of local history in the context of wider forces. The medium of the architectural drawing served as an excellent visual and material resource for this scope of enquiry, superior to historic photographs in the variety and type of information revealed. Most projects encountered in the drawing selection process included multiple sets of graphics, occasionally fifty or more. Beyond the envelope of a building as represented by the facade, plans, sections and details permitted inspection of the construction technology, rationale of the internal space to the elevation and the relationship of the individual units to the whole. While most of the drawings selected for the exhibition and catalogue were facade elevations to accentuate a project's visual integration and recognition, especially for a local audience, a sufficient variety was represented to indicate type. Some drawings, for example, contained both an elevation and plan on the same sheet, others a section and elevation while a few were section or detail graphics alone.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 217 More important than type, however, was the style and support medium of drawings and their development over time, which indicated the audience intended, whether client or contractor (and, in some cases, both). When combined with documentary sources, these features described the visual coding and grammar used by the architect or would-be architect in his organization and management of a building project from the drawing board to completion. Drawings were a significant element in the rise of the architect to professional status from his origins in the building trades during the nineteenth century. Other factors influenced this result, including the architect's design skills, ability to manage within a budget, sense of professional coherence and the receptiveness of clientele but the development and diversity of architectural drawings embodied this rise in material form.

18 As the architect headed in the corporate direction through partnerships and draughts-men, the appearance and substance of his drawings changed. From the splendid watercolour rendering on heavy Whatman paper to tinted linen and, finally, tracing paper for blueprints, the drawing became more businesslike and easier to reproduce for both client and builder. This was the general course at any rate, although the actual evolution of drawings for both parties was more complex. By the end of the exhibition's coverage in 1914, the client and builder (or general contractor, subcontractor) were dependent on the architect's ideas as expressed in drawings.

19 While the rise of the architect in Saint John emerged as the primary research theme, there were a number of important sub-themes. The level of stylistic and technological maturity shown by local architects was confirmed in comparison with similar efforts in other parts of Canada, especially during the second and third quarters of the nineteenth century. In addition, the relationship between the architect and engineer was examined as these became separate but complementary professions after 1850. Attention was also given to the development of the builder from house carpenter or mason to that of general contractor by the 1870s. Finally, the "art architect" phase of the same period was described as this intertwined with the creation of a new city following the Great Fire of 1877 and a very active fine arts scene. Like the architect's advance within the construction industry, these themes gained visual and material expression, directly or indirectly, through the medium of the architectural drawing and were expressed, it is hoped, in the selections made for the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue.